Tactical Analysis: José Luis Mendilibar’s Sevilla

It has been a rollercoaster campaign for Sevilla. After a sensational three-year spell that would see them finish top four on three straight occasions as well as win the Europa League, Sevilla sacked Julen Lopetegui on October 5 after picking up just five points from seven matches. The return of Jorge Sampaoli as manager failed to quell the storm, with the Argentine getting sacked after a dismal run of form that would see them kick off March with a 6-1 loss to Atlético Madrid, a 2-1 win against Almería, and a 2-0 loss at Getafe.

Sampaoli was sacked with the club just two points above the drop, and his replacement was José Luis Mendilibar. After an epic six-year spell in charge of Eibar that culminated in relegation, Mendilibar took charge of Deportivo Alavés midway through the 2021/22 season but lasted just four months, leaving the club in last place and paving the way for the club’s relegation. Nearly one year after his exit, he returned to management on March 21 and took the reins in Andalusia.

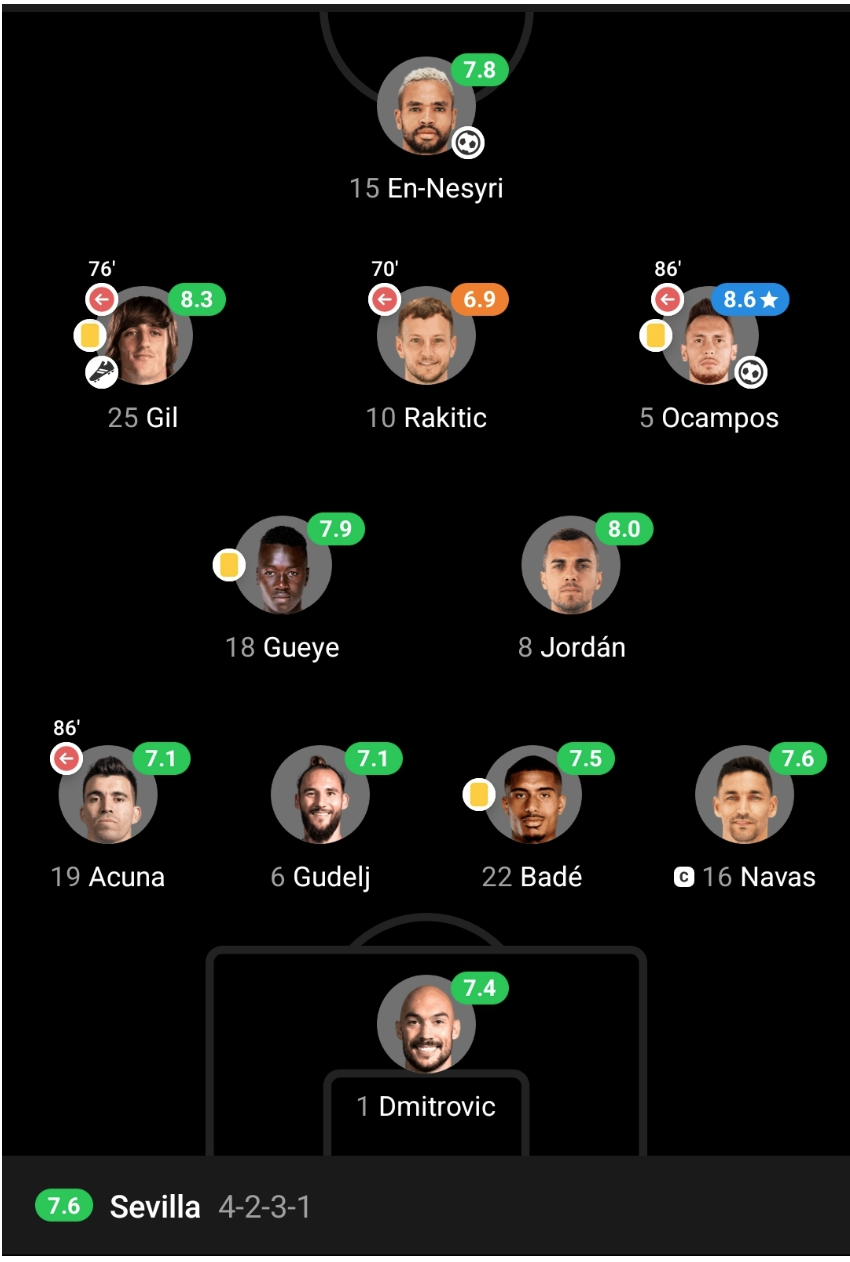

Photo: FotMob

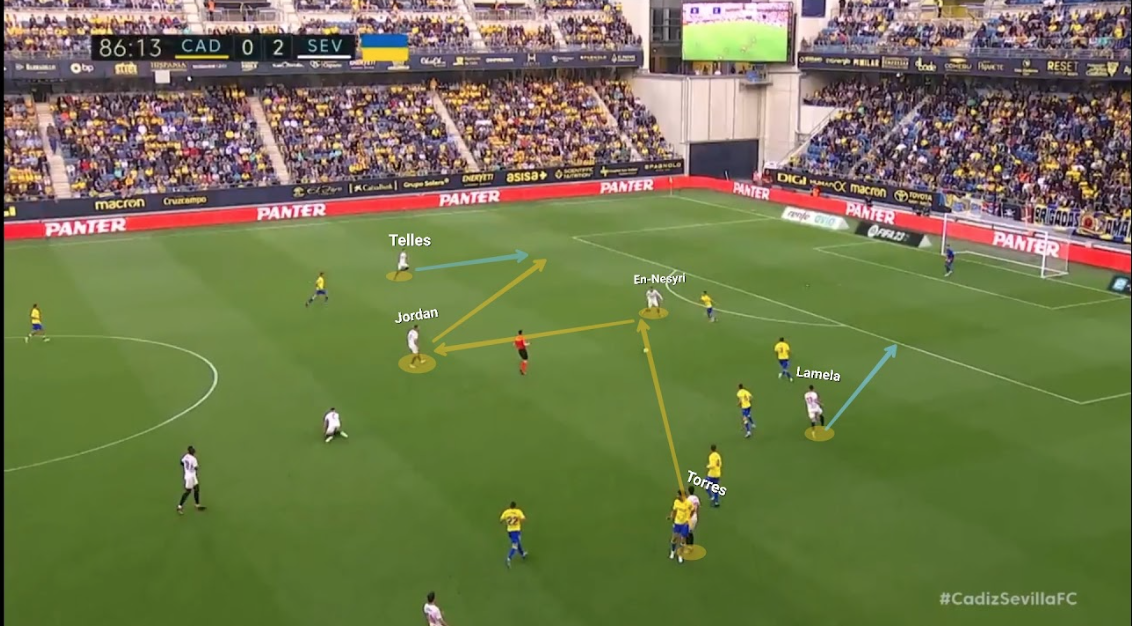

In his first game in charge, Mendilibar went with his trademark 4-2-3-1 formation with Marseille loanee Pape Gueye pairing Joan Jordán in central midfield. Sevilla would prevail 2-0 at Cádiz via goals from Lucas Ocampos and Youssef En-Nesyri, securing their first away win since October 15, before going ahead 2-0 only to concede two late goals and draw 2-2 at home against Celta de Vigo.

They would bounce back from their late capitulation and close out April on a strong note, beating Valencia, Villarreal and Athletic Club and eliminating Manchester United from the UEFA Europa League, before kicking off May with a 2-0 loss to Girona, a comeback 3-2 win against Espanyol and a 3-0 win at Real Valladolid, as well as a 1-1 draw to Juventus in the first leg of the Europa League semifinals.

In their opening match under Mendilibar, Sevilla sought to go direct in their goal kicks by having Serbian goalkeeper Marko Dmitrović boot long balls up the pitch, ditching the careful build-up system that had been used under Sampaoli and capitalizing on En-Nesyri’s height to win aerial duels and lay it off to a teammate or win the second ball and force a turnover with their attacking midfielders constantly looking to pounce and win the ball back.

In Possession

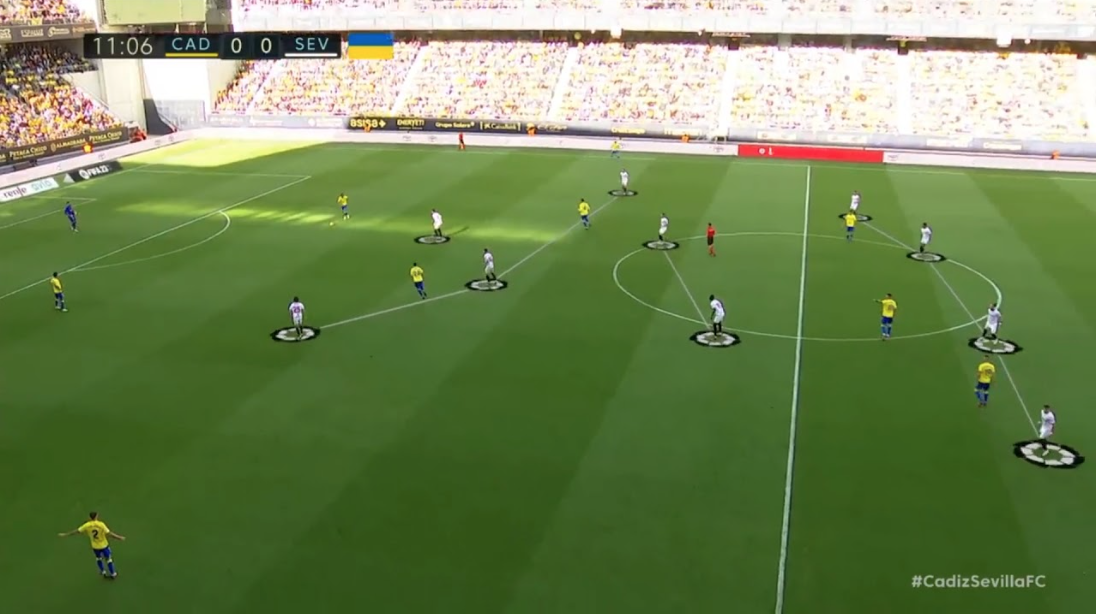

One thing that has come to define Mendilibar’s Sevilla in the middle and defensive third is their ability to bait the opposition into pressing with a numerically equal or inferior setup. The opposing block jumps and matches them up, far from ideal if you want to pin the opposition back in their half and or play through & around them with superiorities.

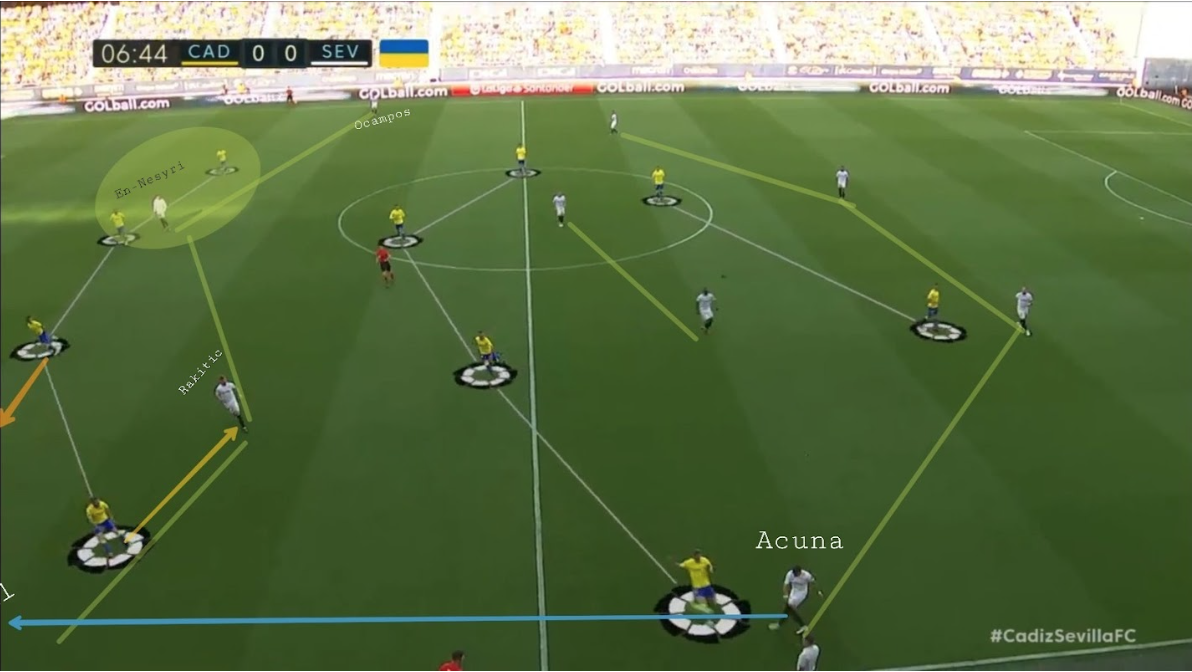

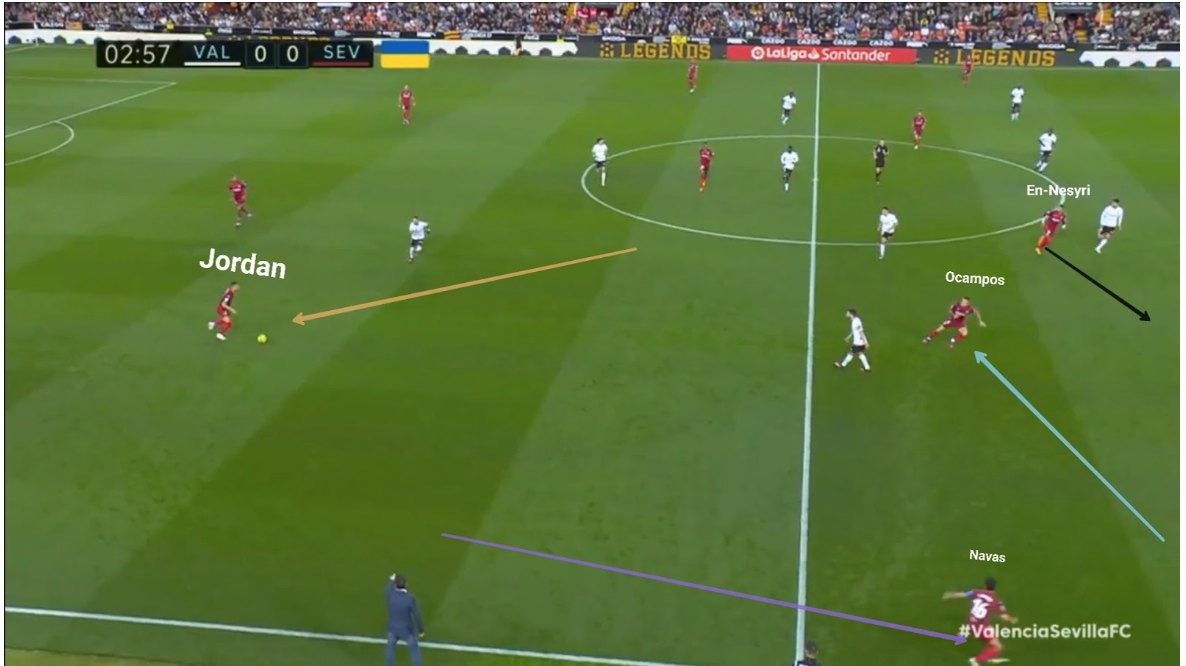

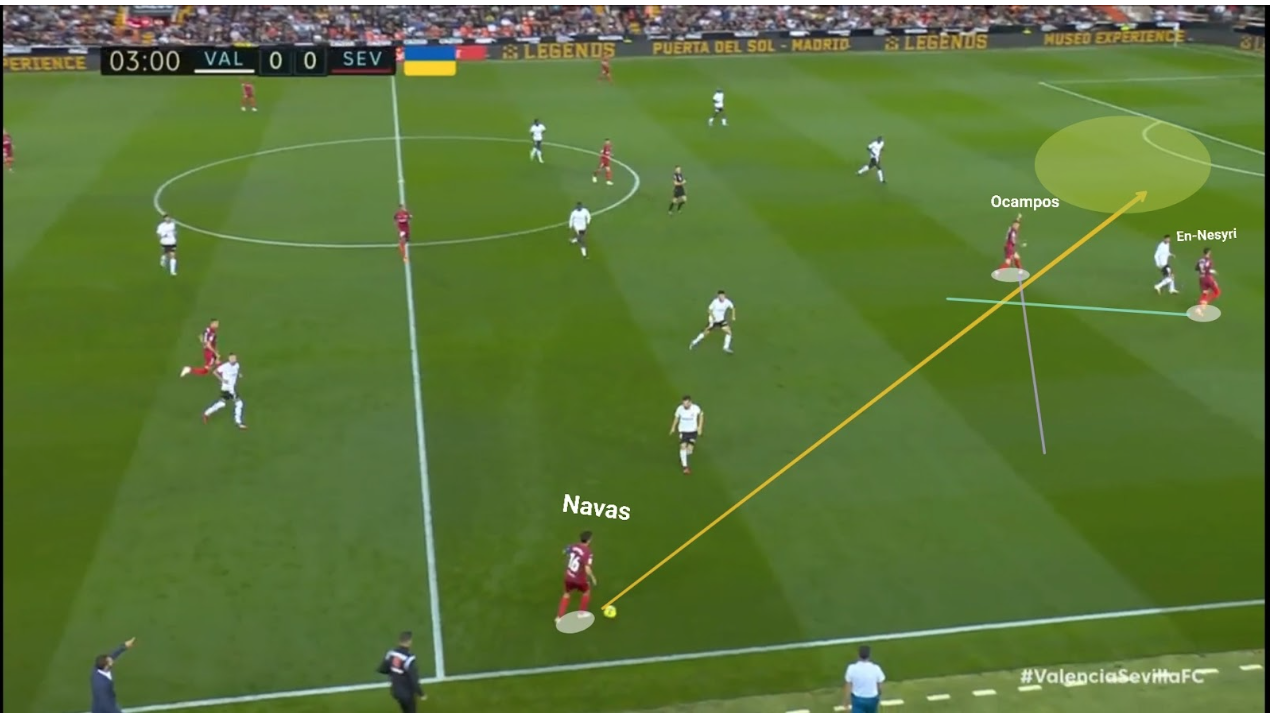

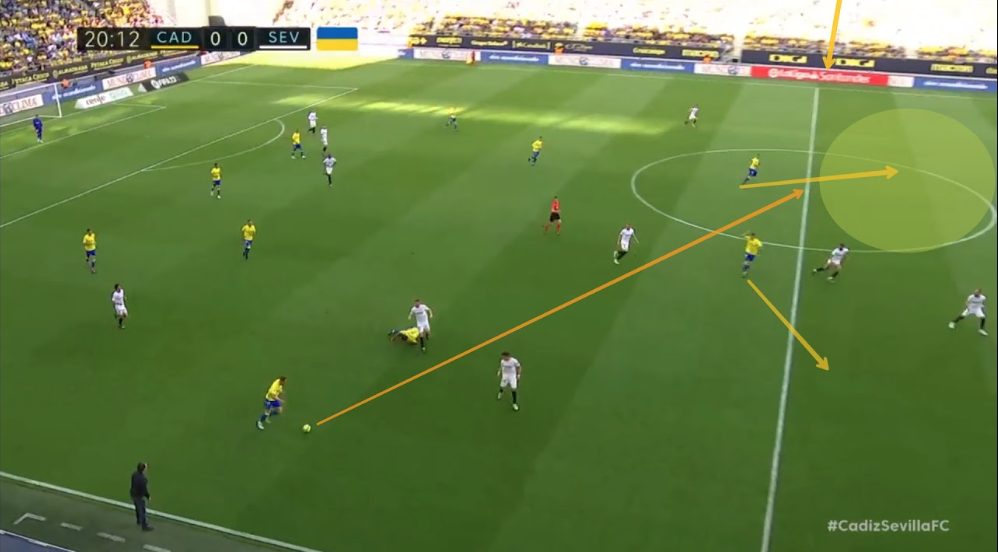

But here’s the subtle difference: Mendilibar doesn’t want to take the risk of committing a turnover when building through or around — he instead prefers to entice the opponent’s mid-high block, stretching them horizontally and vertically and giving the impression of a stalwart defense by matching up to then trying to exploit the space they leave behind playing ‘over the block’.

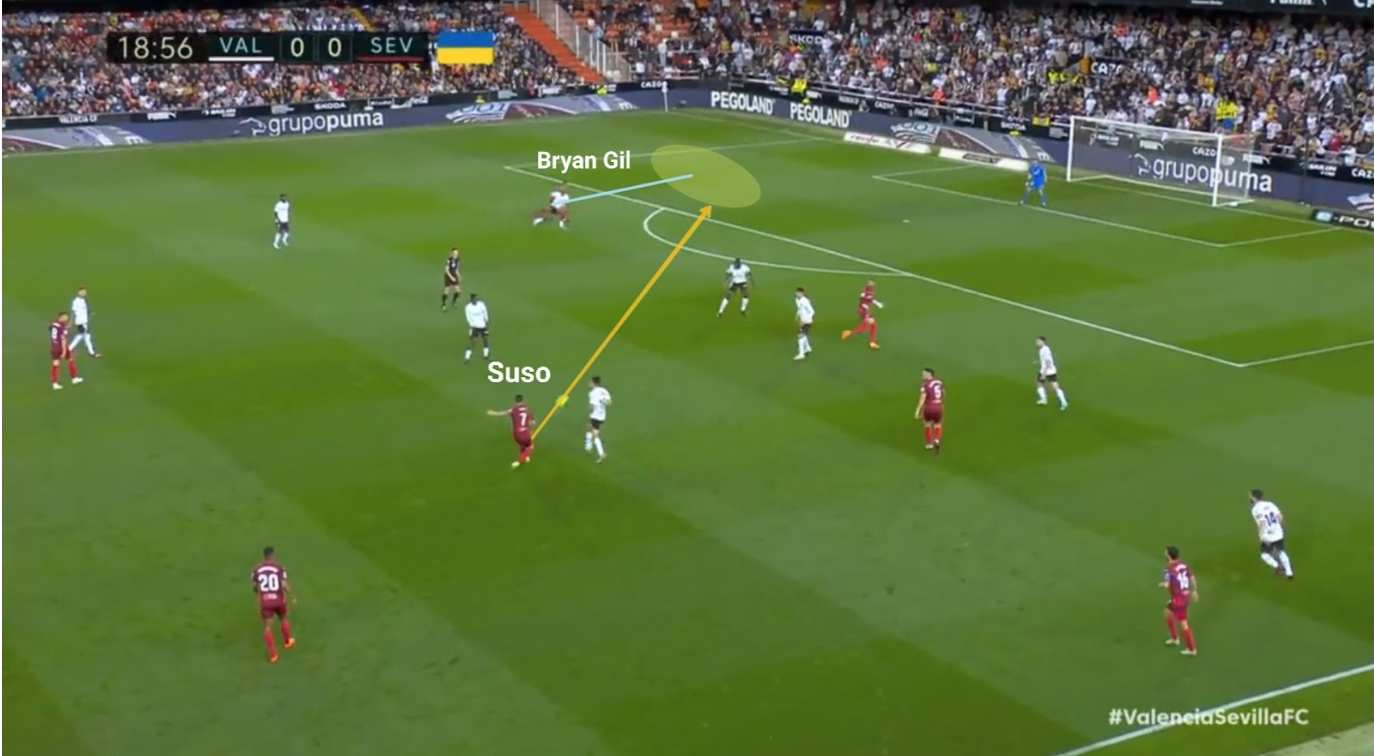

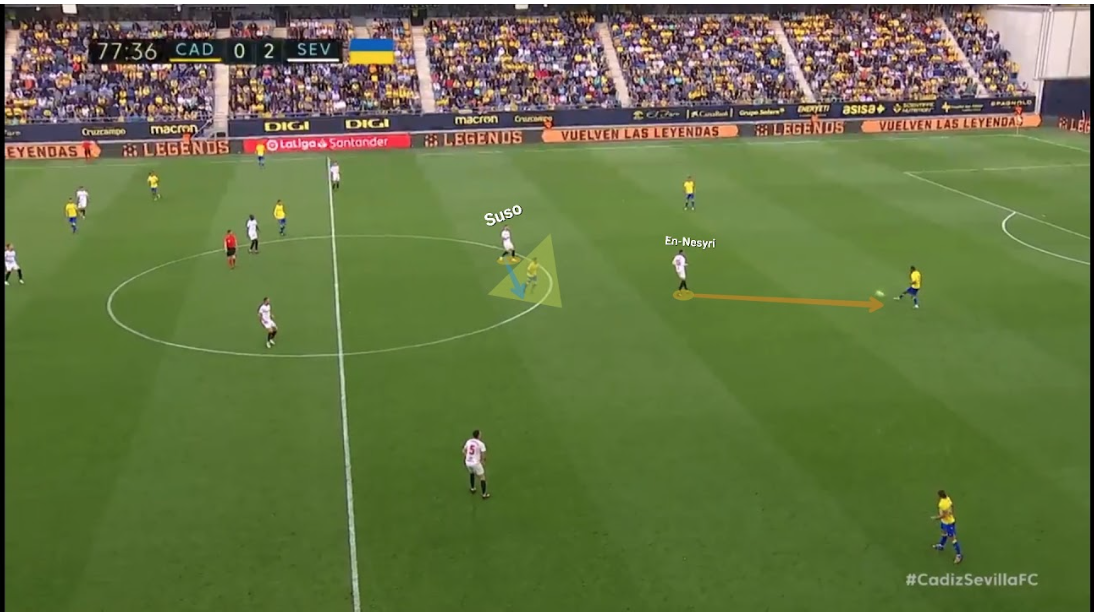

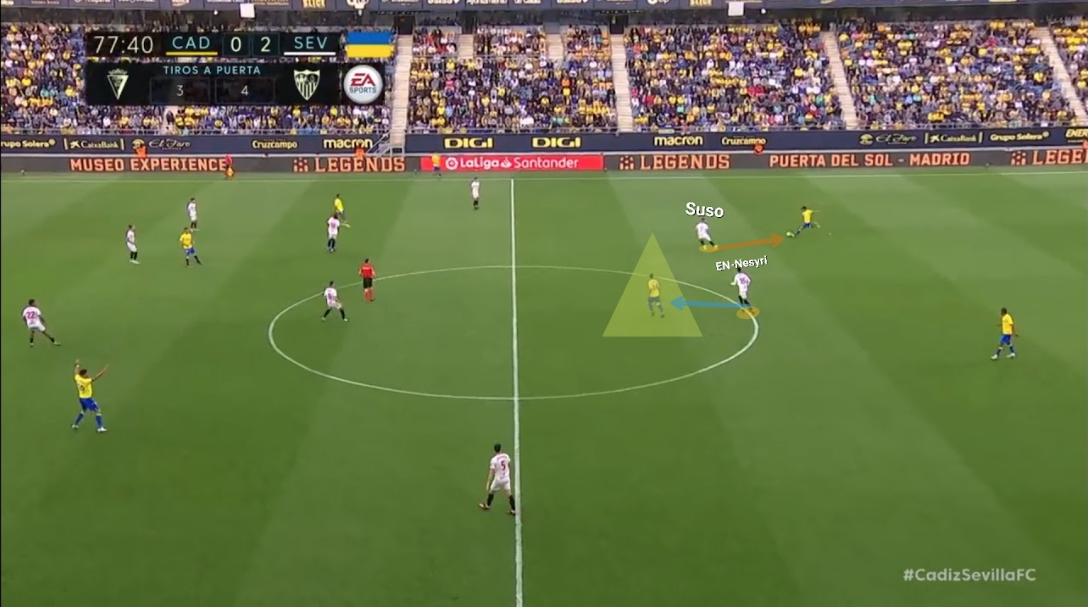

In this case, the trigger is as good as it gets and Suso is already making a perfect run but Jesús Navas opts to carry it forward. There are different ways they’ll try to execute this principle, one of which is a long pass by the defenders (typically fullbacks Navas and Marcos Acuña) to the channels to find their outlets like En-Nesyri, Bryan Gil, Ocampos & Suso in space after recycling possession before giving it to the fullback to entice with their deep positioning, dragging the opposing wide midfielders / wingers out of position.

One of Sevilla’s key principles is baiting the opponent to press before exploiting the space in behind with an incisive long pass. This is effectively a fail-safe option as it leaves no risk of them giving the ball away in a dangerous area, and it allows them to provide a threat by playing a first-time ball around the edge of the channel when the opposing defense has stepped up.

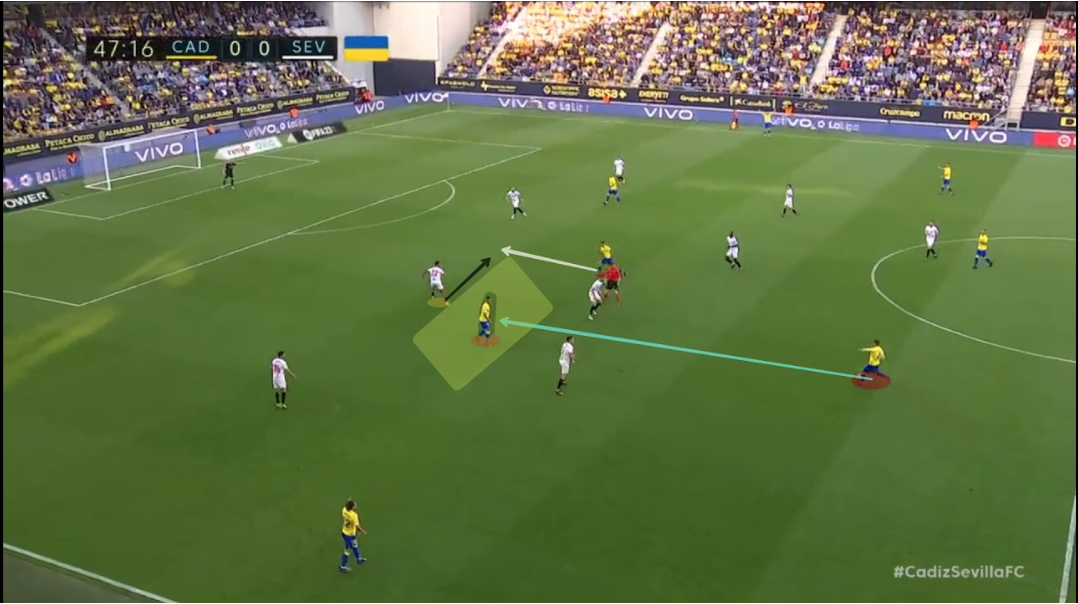

What about Plan B? It’s a long pass from 23-year-old center back Loïc Badé, who arrived on loan from Rennes after an unsuccessful loan spell at Nottingham Forest. Here, Badé plays a long ball to Gil who lays it off to En-Nesyri, who arrived late into the box with a curved run. Rather than recycling possession and enticing the opponent to press, Sevilla opt to play direct and penetrate the defense with the Moroccan forward getting in behind and timing his runs to perfection.

The aim is to find the outlet in space or at least in favorable qualitative superiority circumstances (2v2, 1v1), but if not, the run of En-Nesyri will help to stretch the opposition block and create space between the lines to win the loose ball and carve out a scoring opportunity.

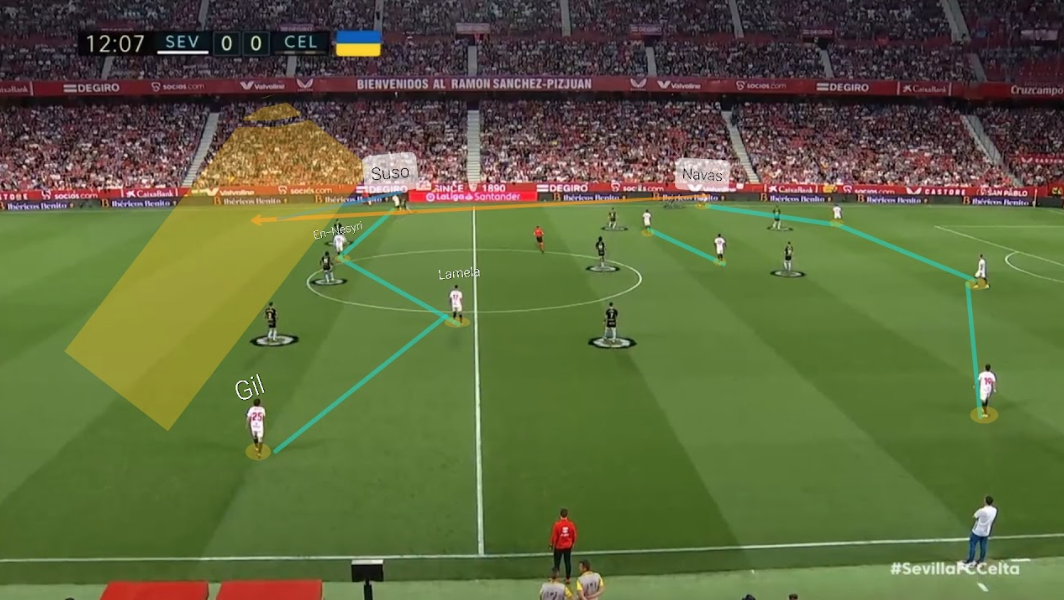

In order to keep their opponent guessing, Sevilla would have their wingers come close to their own fullbacks, enticing the opposing fullbacks to follow them, thus leaving space in behind. Here, we see how En-Nesyri pins the two center backs and leaves the vacated space still unoccupied and enabling Suso to arrive into the vacant space and receive a long ball from Navas.

Creating Chances

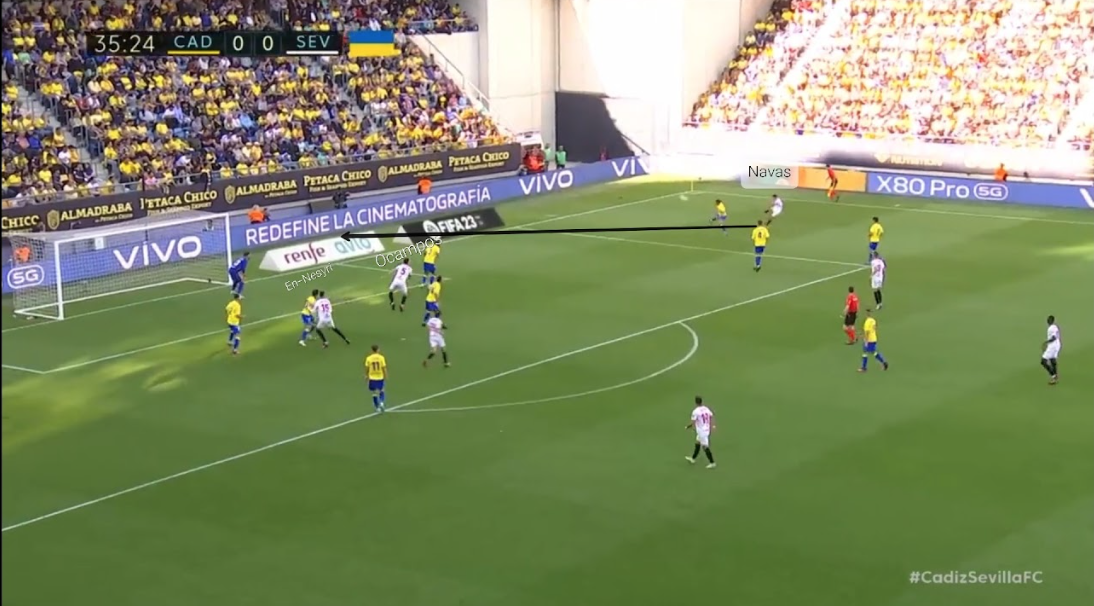

After progressing the ball higher up the pitch, their creation method varies based on the profiles at their disposal. When they start with a right-footed RW or RB, their preference more often than not is to cross (out-swinging) it from the flanks.

“If I put 15 crosses into the box, I know I won’t finish them all off, maybe only four of them. But if of the remaining 11 I win seven rebounds being close to the play, defending forward, that’s already 12 attacks out of the 15 attempted. It seems that if it is not a cross to someone’s head it is a raffle, just like when you clear it. Not all of us can defend with the ball; for that, you need a lot of quality,”-Mendilibar.

One thing we noticed from these scenarios is that the attacking midfielder (interchanging) who is also right-footed refuses to exploit the space and give his teammate a passing option with a curved or underlapping run for a cutback. He even rarely attacks the box for those crosses, and if he does it, it’s with hesitation. That might be because of the conservative nature of the manager & his insistence to keep his team compact and deal better with transitions, whilst Navas is also providing an option with an overlapping run. That also means they value En-Nesyri’s box presence a lot, with Mendilibar stating prior to his arrival at Sevilla:

“When there is a lateral cross, one of my two midfielders loads the area, and the other one approaches to win the second play. If we don’t play with a striker duo, the midfielder has to go. I don’t want the opponent to win the rebound.”

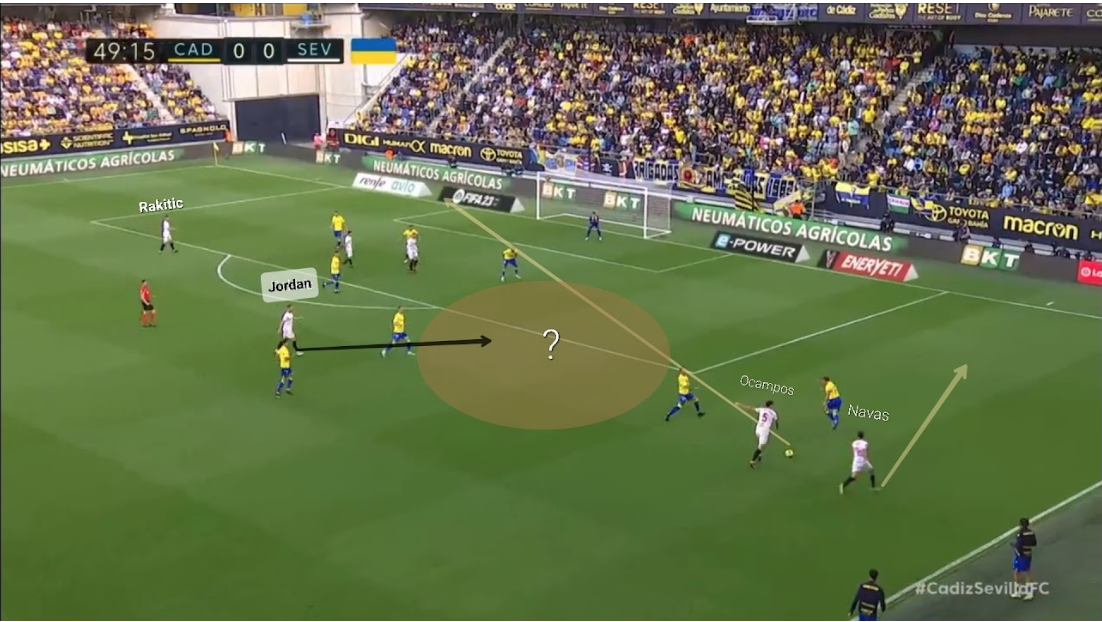

Here they weren’t playing with two strikers from the get-go and instead tasked the ball-far winger to crash the box and act like a second striker. We can see how Jordán refuses to enter this space, as he knows that if the ball is on the flank with two players charging forward, the go-to option is likely a cross rather than a combination play. Jordán needs to be wary of not pushing too forward and leaving Sevilla exposed on the counter, with Ivan Rakitić already moving near the box.

Now, what if they had left-footed wingers or attacking midfielders on the right flank? Well, in that case, their creation method completely differs. When they have that kind of players who are either left-footed or even right-footed but with much better associative play, their direct approach disappears and they become more settled in possession.

They try to overload one sector of the pitch around the ball and interchange positions, inviting pressure from the opponent by dragging them out of position before catching them by surprise and playing in a different gear. In doing so, they can create scoring opportunities and exploit Suso’s creative prowess in executing through balls to find quick outlets in the wide areas.

Against Valencia, they executed this well on the left flank and didn’t even need an overload. By utilizing quick, clever combination play and positional interchanges, they threw the opponent into disarray and ended up scoring another goal via a cutback to secure the victory against Los Che.

Players adjust their position and angles of support towards the ball carrier, allowing them to escape pressure seamlessly and generating space between themselves, as seen below with an up-back-through passing pattern.

Dynamic/Fluctuating Width

Sevilla apply this concept mainly in the middle and final third. Here, for example, Jordán stepped out of his position from the double pivot to act as an auxiliary full-back, giving the license for Navas to venture forward. With Navas pushing forward, Ocampos decides to tuck inside into the right half-space, making a complementary movement and creating a problem for his marker. The opposition FB is caught in limbo as he can’t follow him inside in order to not vacate a huge space for the RB. He stands still, allowing Ocampos to roam inside.

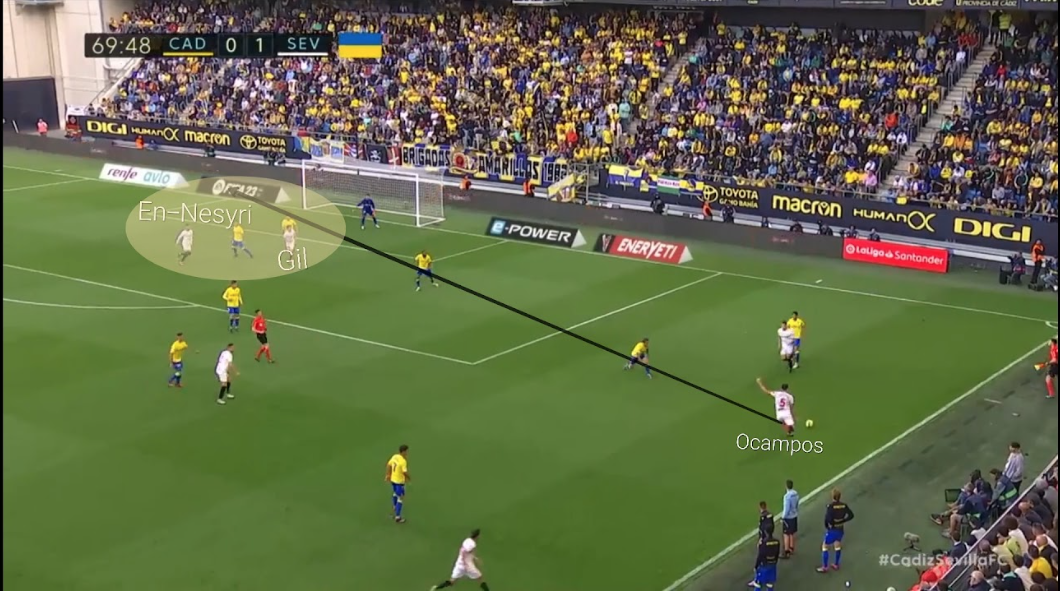

En-Nesyri stretches the opposition with his off-the-ball run dragging the left center back to the sideline which creates a space between him and the right-sided center back that was exploited by Ocampos’s infield darting run to the far post. The ex Marseille man received the ball behind the opposition’s high line as a second striker, arriving into space and creating a dilemma for the opposing defender.

In the below example, the full-back & winger (Ocampos and Navas) invite and eventually bypass pressure. The opposition is drawn to the wide side of the pitch to provide cover and prevent an overload, which creates space for the ball-far winger or the attacking midfielder to drift inside & interpret pockets of space. They also do this to occupy the vacated space in crucial positions in the half-space with counter-movements.

In this instance, though, En-Nesyri draws the CBs deep by stretching their backline with a run to the back post, creating acres of space ahead of the box in the right half-space. This time, Ocampos was tasked with creating rather than crashing the box, and Bryan Gil made a run to the byline to receive the through ball from the Argentine. Again, they benefited from these opposite movements to create scoring opportunities, but the end product wasn’t optimal.

Manipulating the Opposition Block

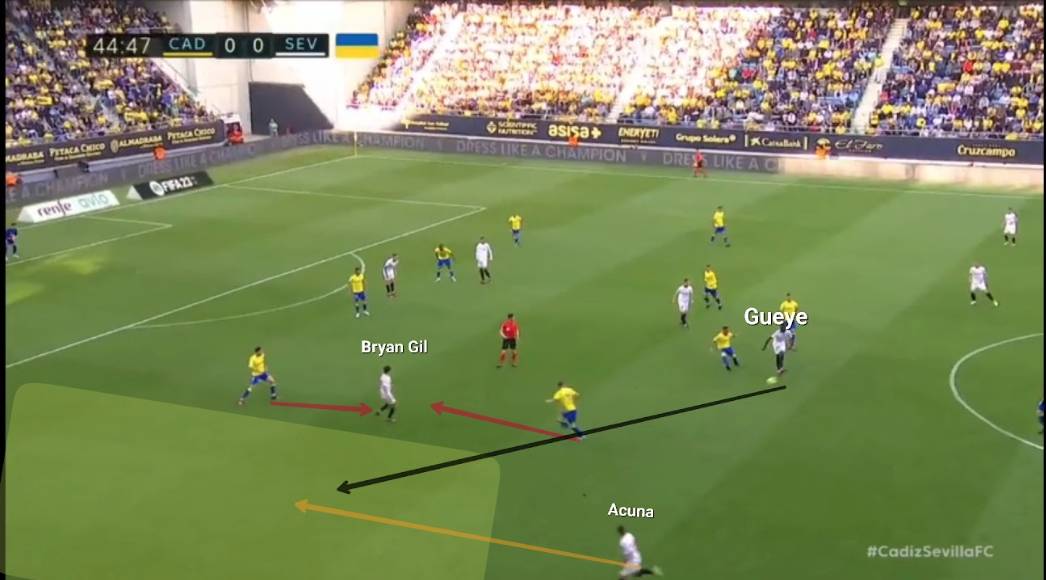

One of the ways Sevilla tries to generate space is by cleverly manipulating the opposition’s defensive structure in their counter and dynamic movements.

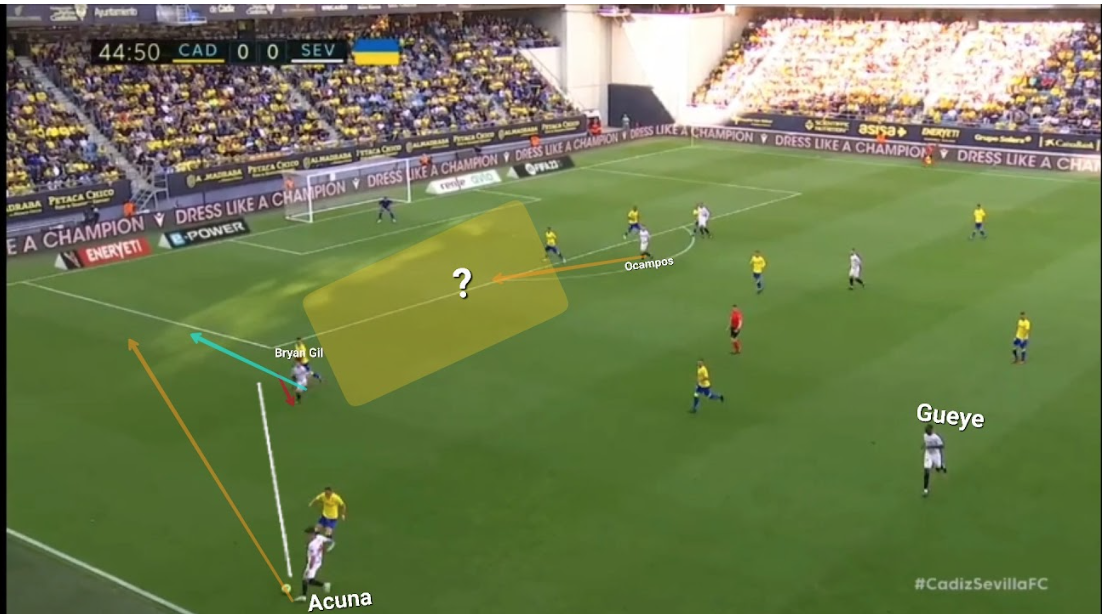

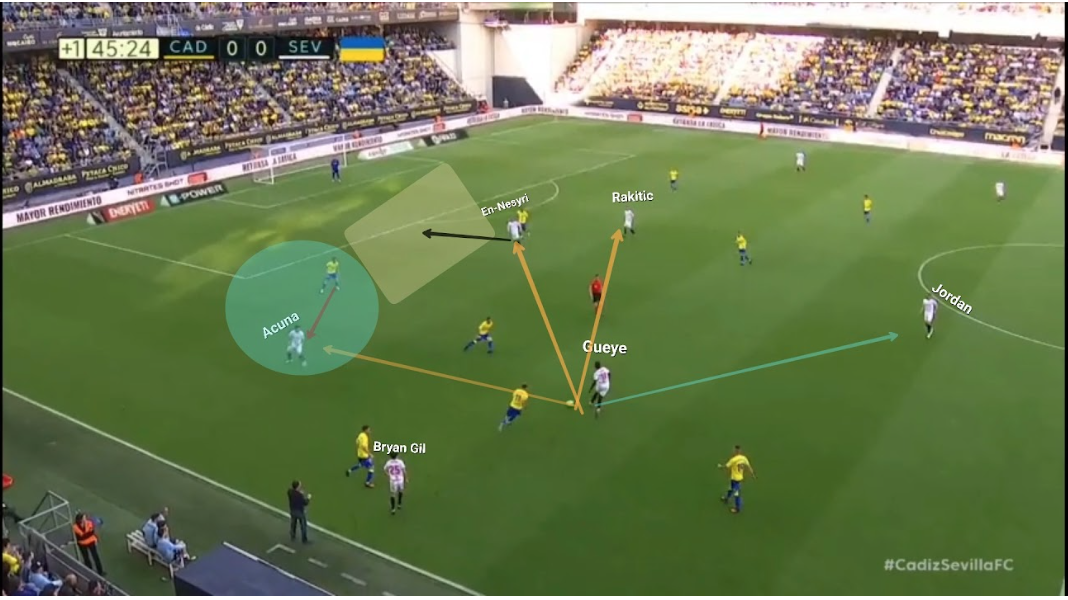

Here we can see Gil drifting inside towards the ball-carrying midfielder to provide support, but not in a direct way but rather by a shadow manipulation. He knows his movement will attract the opponents towards him, vacating space on the flanks as the preference is to protect the middle and close the passing lanes. Acuña makes a complementary movement to arrive and occupy that space, giving a clear passing option for Gueye.

But Gil’s job isn’t done yet, as the pass by Gueye lacked pace and allowed the opponent to have time to reorganize & adjust his positioning. Because of that, Gil runs to the sideline where the ball carrier is located, luring the opposing right back with him and opening up a massive hole between the opposing right back and right center back. Nobody from Sevilla tried to capitalize on that and the opponent’s wide midfield managed to close that passing lane & forced Acuña to go back or venture outside, but the Argentine opted to pass it to Gil instead.

From then onwards, Gil and Acuña swapped positions and made a good combination play, working the ball to Gueye. The latter had the chance to speed up play by passing to Acuña with his outside foot, En-Nesyri with his right foot after letting the ball come across him, or make a first-time pass to Rakitić.

Gueye opted to make the safe option by passing it to Jordán in order to control the tempo and slow the game down, buying time for his team to be well-organized in case of a turnover to deal better with transitions. Does their gaffer prefer or emphasize this though? Maybe not.

“I want us to figure out whether we can do things more quickly or sometimes more directly because it’ll help us, stated Mendilibar in an interview with Relevo‘s Albert Blaya earlier this season before joining Sevilla. “Play on the outside, get the ball out quickly to the side or winger, and cross quickly without waiting to reach the bottom line.”

Out of Possession

When we come to the defending phase of their game, they alternate in their preference to recover the ball. Their go-to option is to defend in a high block in a hybrid of zonal & man-oriented pressing.

En-Nesyri forces the goalkeeper to either kick the ball long or play into their hands with a risky short pass, and we can see here that Navas intercepts the pass and tries to create a chance by whipping in a cross from the byline.

Those two pressing sequences were from the opponent’s deep build-up play involving their goalkeeper. If they’re calm and technically secure, they become a bit passive and measured in their pressing to prevent inferiority & getting exploited.

They split the defenders and force a pass to the sideline and then exert the right pressure to recover the ball, forcing a mistake or making them go long.

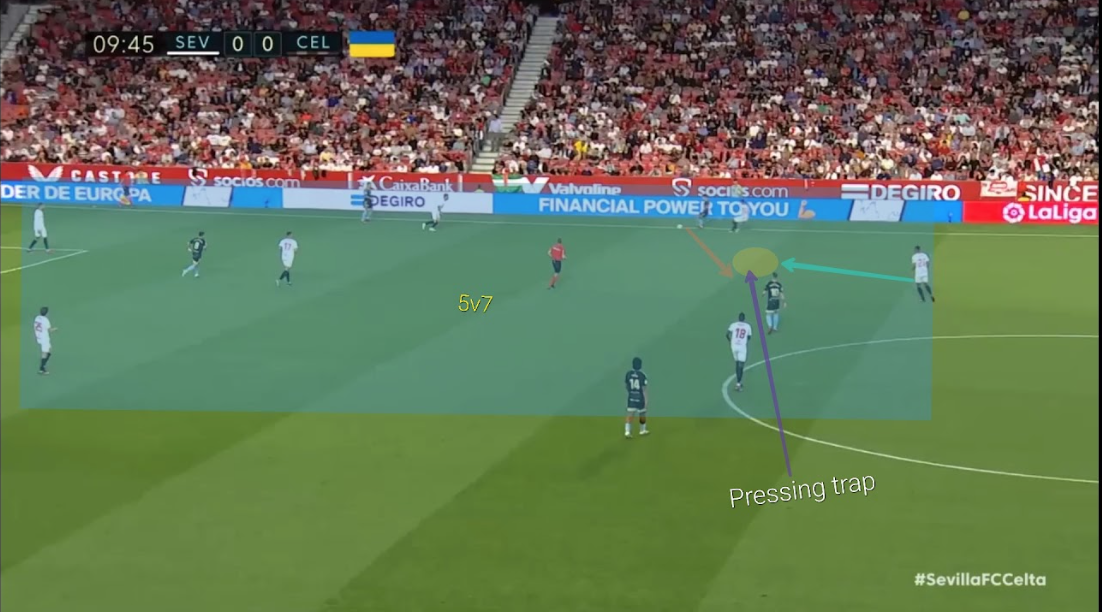

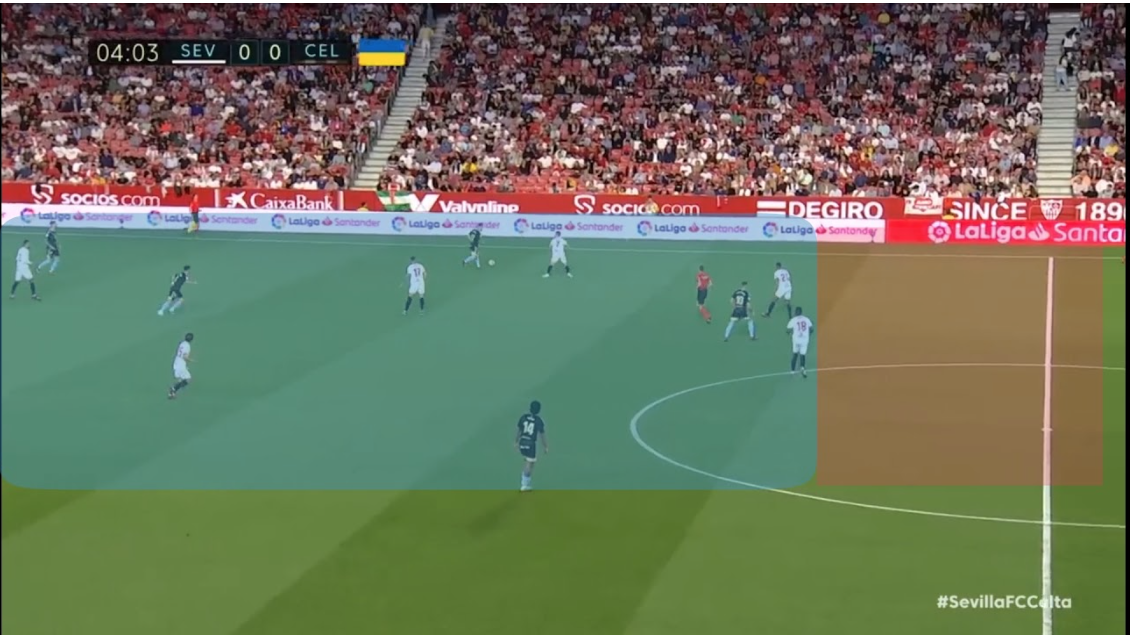

Here against Celta, we can see how after their left-center back passed the ball to the left back, En-Nesyri made a curved run to prevent a back pass and give the fullback a dilemma: to go long or make a pass to their wide midfielder/ winger. They’ve matched them man to man and with Navas stepping up, Sevilla can squeeze the pitch to outnumber the opponent and use the sideline as an extra defender, helping them to recover the ball pretty easily by setting a trap in the pockets of spaces.

One of the issues was when they pressed high, the distances between the first, second, and or third lines of defense were massive, in particular, due to the defenders staying deep while the forwards were pressing high. As such, their pressing structure was disjointed.

The first leg against Manchester United is a prime example of this. The defenders didn’t want to back the press while the players higher up the pitch were going man-to-man in a passive settled block, trying to wait for triggers before activating the high press. That created a big hole between the lines which Manchester United capitalized on by sending long balls to their creative players, making Sevilla susceptible to transitions.

Mendilibar acknowledged these issues in his post-match press conference, stating: “Our game plan is the same but our opponents also have their own, Manchester United were able to get out of their half and that pinned us back.”

Moving back to the Valencia game, we can see how Sevilla’s 4-2-3-1 mid-block aims to force a turnover by closing the passing lanes to the flanks. The two players up top are in charge of screening the opposition’s central midfielder, interchanging their positioning based on the ball’s route.

When the ball is with the right center back, the ball-near forward jumps on him while the ball-far forward tightly marks or puts the central midfielder under his cover shadow, preventing a pass in the middle. When they get pinned back into their half by a technically secure team, they end up in a well-organized low block varying based on the opponent’s strategy, enabling them to opt for a 4-4-2 or a 3-5-2 low block.

However, there were some occasions when they suffered while defending in a settled back with the opposing forwards escaping the marking of the Sevilla defenders and getting into dangerous situations, as seen in the below examples against Cádiz and Manchester United.

Here, their right back was dragged higher up the pitch with Jadon Sancho dropping deep to provide support for the ball carrier. In the meantime, the opposition’s left back moved higher up, tucking inside and interchanging to occupy different crucial spaces and create problems for the opponent. Ex-Sevilla man Anthony Martial lured Sevilla’s right center back to the sideline, creating acres of space in their backline after Lisandro Martínez’s line-breaking incisive pass.

This threw their block into disarray and saw them lose their markings and their concentration, to the extent that they conceded a goal with Bruno Fernandes playing a line-breaking pass and Marcel Sabitzer exploiting the space and breaking the deadlock. Against Cádiz, they suffered with these counter-movements and line-breaking passes.

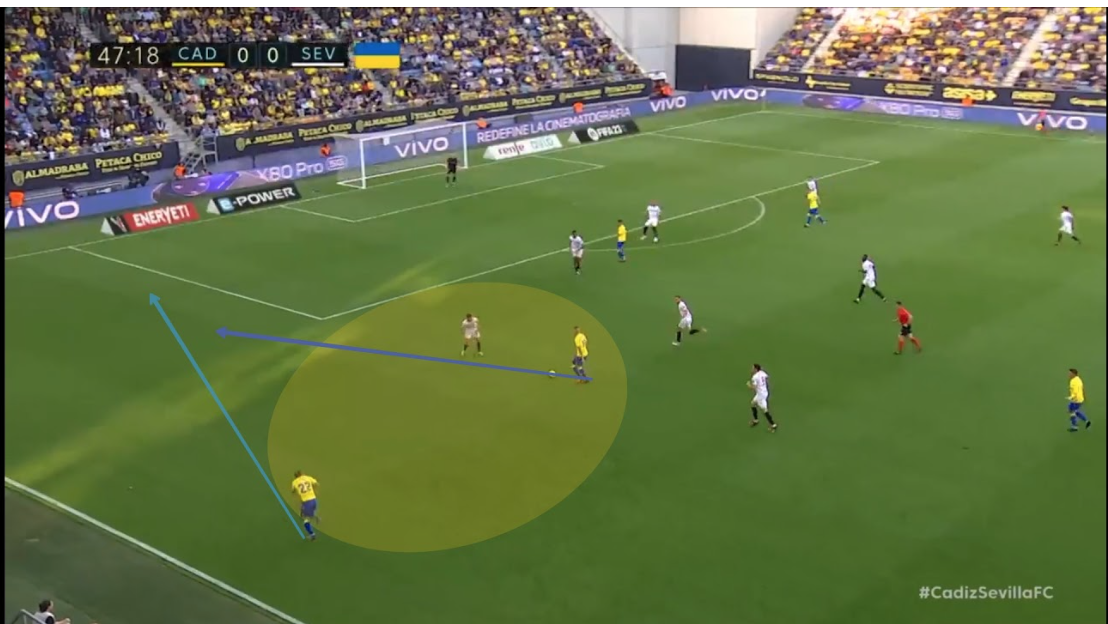

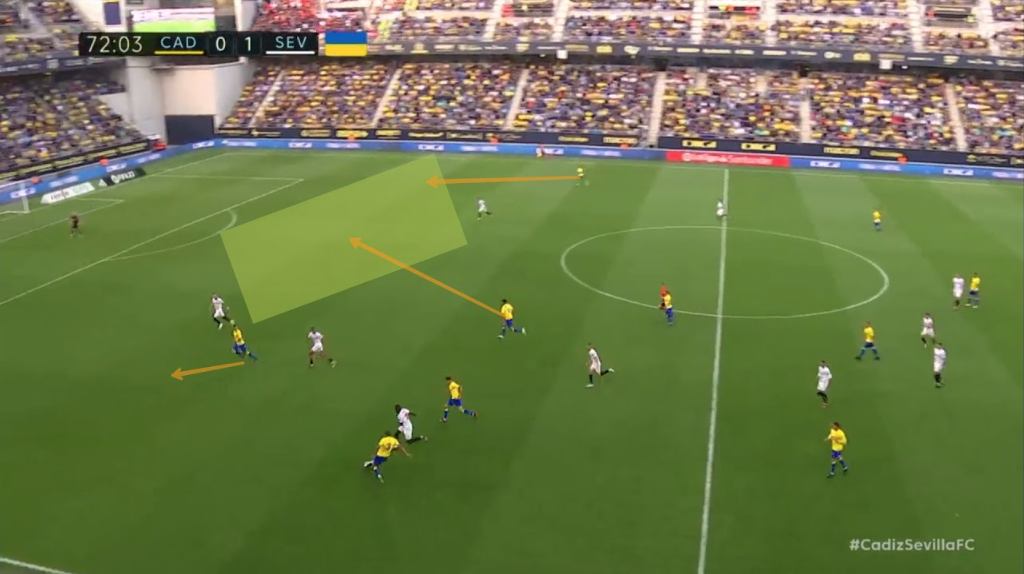

Here, Loïc Badé was tightly marking the opposition’s forward, whilst Ocampos was closing the passing lane but Jordán failed to recognize the situation and was drawn to the forward, forgetting the player he was supposed to mark and getting caught ball-watching. This player spotted the vacated space and started a darting run on his blindside to capitalize on the occasion, giving a passing option to his teammates.

The young French defender spotted this and decided to track that run, leaving the player he was previously marking free as he thought Ocampos and co would deal with this to compensate.

The Cádiz ball carrier made an incisive line-breaking pass to find his teammate in the pockets with space to turn and provide a threat. Mendilibar admitted, “In Cadiz, we struggled with balls into the box and through balls.”

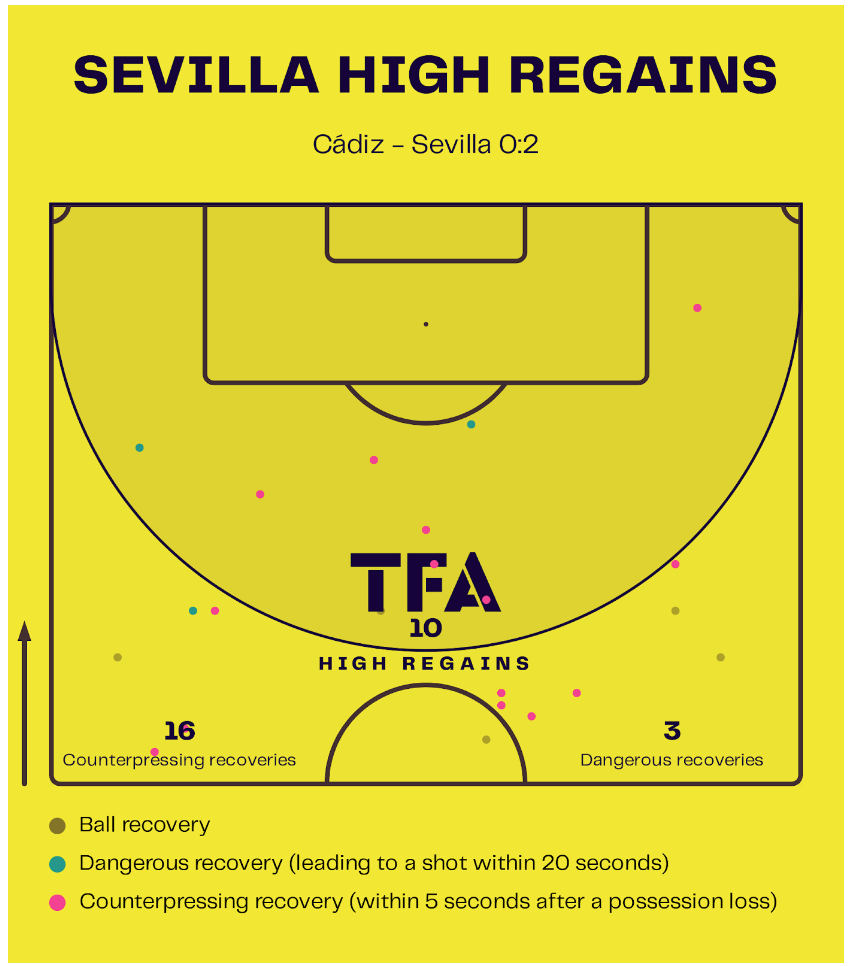

In general, though, despite these shortcomings, their pressing caused teams all sorts of problems in both legs against Manchester United and Celta de Vigo, as seen below.

Photo: Total Football Analysis

“I like aggressive football, which always seeks to attack and is played in the opposite field” – Mendilibar.

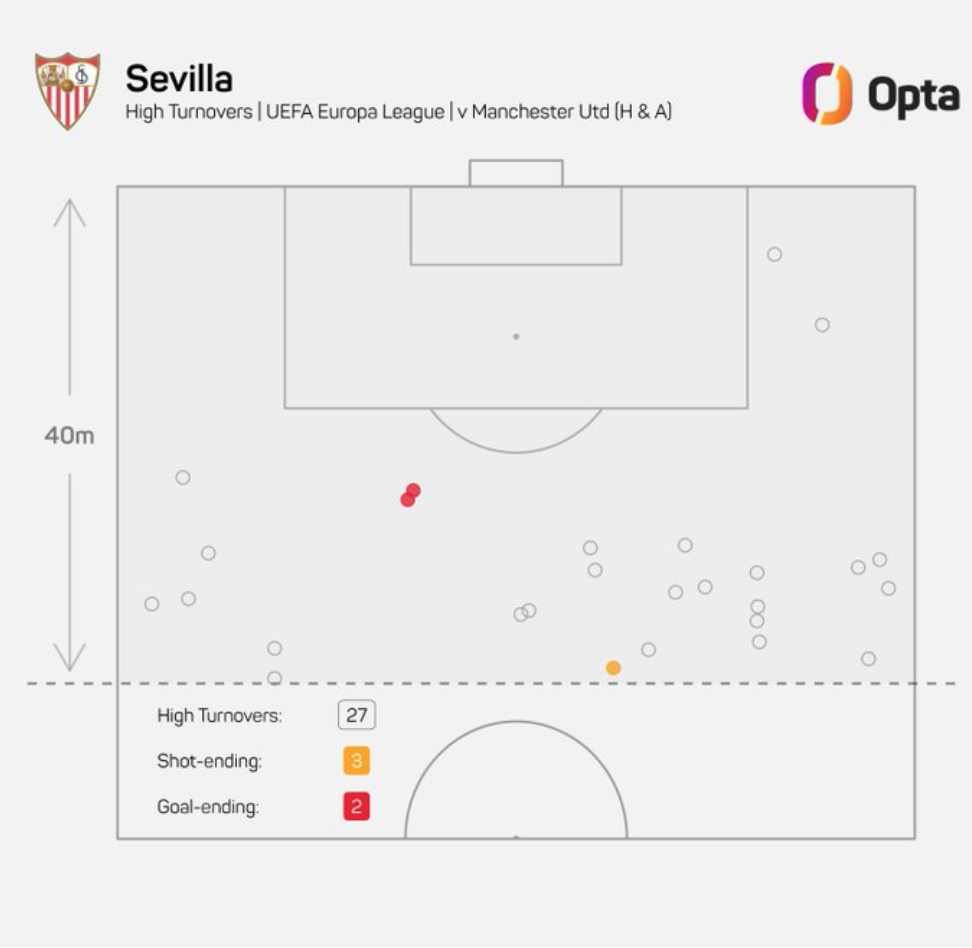

Photo: Opta

“Attack and defense are the same thing. You defend well, you attack better. When you attack better, you are more aggressive without the ball. You cannot split them, you cannot talk about those two things, not at the same time,” – Pep Guardiola.

Game of Transitions

One thing that is clear from Mendilibar’s short tenure at Sevilla thus far is how chaotic the games have been. Whilst there are certainly individual issues, Sevilla’s susceptibility to transitions stems from the gaffer’s ideology. It’s a byproduct of his system screaming chaos: you’ll struggle to recover the ball upon turnovers unless you work diligently as a team.”

“If it ends with a goal, it doesn’t matter to me whether it has been three touches or 16. I am not against anything in football, but there are certain things that I prefer to others. I don’t want to take too many risks in our own box but do this in the opposition’s, and this is what I have always wanted, not just now,” – Mendilibar.

It’s not his fault that his players were easily getting dragged out of position in the rest defense with opposite movements, but the constant desire to play direct and failing to emphasise control can help to explain their glaring issues when it comes to defending transitions — as such, Sevilla allow opponents to reorganize and make intricate sequences and struggle to protect their defense when they lose possession.

It goes both ways, though — on the flip side, his team also creates numerous opportunities to score via transitions, exploiting his outlets’ individual quality. It can be from winning the second ball in the middle after a long ball from their GK or by pressing high up and forcing a turnover, or capitalizing on the opponent’s mistake. They have different ways to generate chances through transitions — the problem is the execution.

They managed to get a grand total of zero goals from these offensive transitions because of the lack of execution. The weight of pass, pass selection & timing have been below the optimal level. Overall, the biggest problems for Sevilla to solve with and without the ball are:

° weight of pass

° pass selection

° lack of communication through the ball

° ball watching after the press gets bypassed, forcing the midfielders & defenders to cover a lot of space

° timing of actions

In his recent post-match press conference, Mendilibar insisted on how much he strives for simplicity and why it enabled them to defeat Manchester United:

“I’m just who I am. I’ve been in many teams at all levels. I started in the Regionals and now we’re in the UEFA (Europa League) semi-finals with a good team. I haven’t driven anyone crazy. Especially for the simplicity, which is a fundamental thing in football. We’re the team that’s the easiest to analyze, we don’t do anything extraordinary. We insist upon what we do well and we hardly ever change.”

Sevilla have lost just one match under his tutelage, grabbing seven wins and three draws and securing their top-flight status with ample time to spare. They will be hosting crosstown rivals Real Betis before traveling to last-placed Elche, hosting Real Madrid and traveling to Real Sociedad, but before that, they’ll be hosting Juventus in the second leg of the Europa League semifinals after drawing 1-1 in the first leg.

At 62 years of age, José Luis Mendilibar has spent the past three decades in management, but his sole trophy came in 2006/07 when he led Real Valladolid to the second-division title. Today, he has the chance to lead Sevilla to their seventh Europa League Final, and he has done so by instilling a simple but effective system at the Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán. As the great Johan Cruyff once said, “Playing football is simple, but playing simple football is the hardest thing there is.”

By: @ftblnatt

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Europa Press Sports

References: Albert Blaya’s interview with Jose Luis Mendilibar for Relevo, @TotalAnalysis and Opta graphs in games consisting of Sevilla, Cádiz, and Manchester United, and press conferences from Mendilibar’s time at Eibar and Sevilla.