Tactical Analysis: Juventus vs. Sassuolo

Roberto De Zerbi’s Sassuolo side are the team to watch in Serie A this season, and after an exciting 3-3 draw in the last meeting against the Old Lady, the fixture looked to be both promising and competitive. A late first-half sending off for Pedro Obiang changed the complexion of the match. Nonetheless, the game contained many interesting aspects worthy of investigation.

In terms of chance creation, Sassuolo sought to extend the size of the effective pitch as a way of generating exploitable space. This can be seen vertically through the role of goalkeeper Andrea Consigli and their willingness to play backwards and invite Juventus pressure forward. Through inviting the opposition deep into their half, they reduce the compactness either between midfield and defence or midfield and attack depending on the reaction.

This strategy works particularly well in deep areas as the opponent lose the tool of offside as a way of manipulating the size of the pitch. Horizontally, the planned work when Sassuolo were attempting to build up as the backwards option for the switch of play was typically open to force Juventus two banks to shuttle which would lead to gradual territorial gain until the final third.

However, they struggled to infiltrate centrally during periods of consolidated possession because of the emphasis Juventus placed on remaining compact and protecting the centre. In deeper regions, the possibility of crucial spaces being exploited was evident as Juve rarely took risks to regain possession.

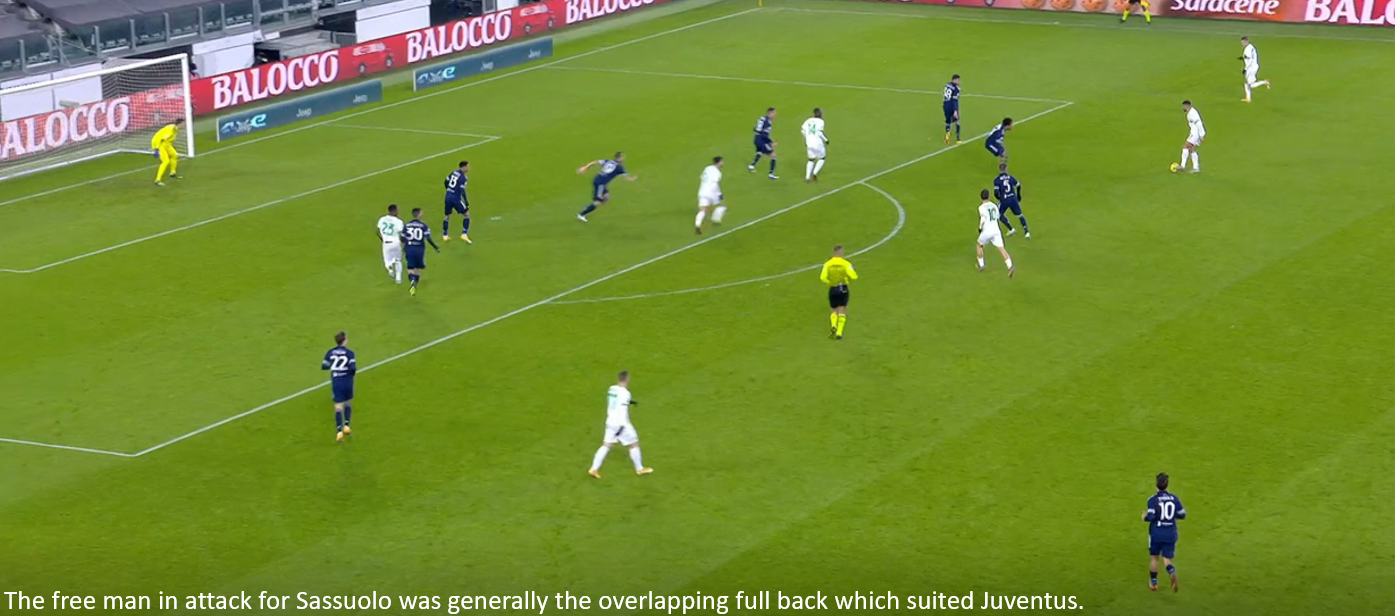

Juventus’s defense accepted the trade-off of potential deep wide crossing opportunities to prevent Sassuolo finding their interior players in between the lines. This had the effect of pushing these interior players wider to receive the ball which then better allowed Juventus to engage in a press as attempts to constrain were made easier as they could use their two wider players available in the 4-4-2 to block inward or backwards passing options.

The two wide players rather than the block pressed as through reducing the size of the effect pitch by pushing Sassuolo deep and wide and forcing the commitment of the interior player, they removed the ball-side half-space as a potential danger zone in the short-term negating the requirement to shuttling meaning the box remained well covered for crosses.

Once Sassuolo started moving into deeper wide regions potential to restart attacks became more difficult due to Juve’s effective constraining which resulted in opportune chance creation methods being pursued i.e., deep wide crosses against a well-covered box. In essence, Juventus were willing to face crosses from Sassuolo if it meant they progressed deep in wide areas as they were less likely to create a goalscoring opportunity directly, successfully recycle the ball or respond well to second ball opportunities.

This explains the passive 2v2 approach to overlapping situations as the fullback would follow the runner but sit off to allow the cross while the wide midfielder would close off the interior player as the passing option again forcing the cross.

One player with a particularly notable performance was Hamed Junior Traorè. The philosophy of positional play practiced by Sassuolo places significant emphasis on the concept of an interior player. This player seeks to receive the ball in between the lines, often in the half-spaces, and draw opposition pressure because of the danger present if left unperturbed stemming from their positioning and quality.

They are tasked with manoeuvring through tight spaces to unlock other worse-covered regions of the pitch, exposing the opponent’s compactness through being less vulnerable to pressing efforts which creates space and time for themselves. Alternatively, if space is present, they can engage directly in short interplay to capitalise upon moments of transition.

In essence, they function as link players between consolidated possession and potential transition which means they are often the individual difference makers. Traorè demonstrated many of the crucial skills required of an interior player, including receiving on the half-turn.

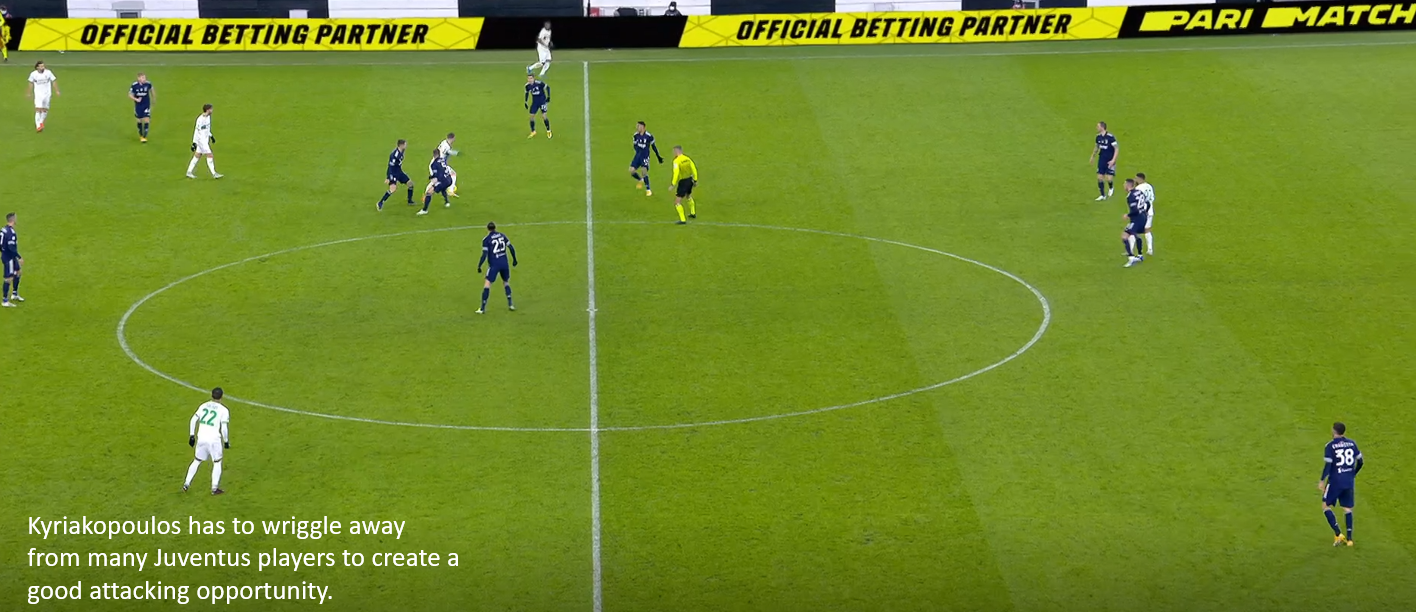

This is where a player has an open body orientation rather than receiving with his back to goal which increases the player’s options overall but most pertinently better facilitates progressive actions, helping to connect phases which is crucial for a transitional player. He moreover demonstrated an ability to weave his way out of compact regions, increasing the size of the effective playing pitch.

In possession, as is common with Sassuolo’s playstyle more generally the fullback and winger would change which vertical zone they occupied depending on the phase of play. In the build-up, the fullback sits narrower in the half-space to ensure centrality and establish a network of short passing connections while the winger sits high and wide to stretch the last line of the opposing defence to better receive directly.

The direct route to the winger being exploited is typically better seen when Jérémie Boga is playing compared to Traorè because of their differing profiles. Boga is more direct and dribbling oriented compared to Traorè’s archetype which is much more like that of a midfielder who seeks to link play. The fullbacks positioning places them in an advantageous region to link with wingers where they can rotate, with this generally leading to the winger moving inside and the fullback moving outside.

This can disrupt opposing cover as to who is responsible for whom temporarily, which generates a free man in combination with central link-up as is demonstrated below with the sequence between Georgios Kyriakopoulos, Manuel Locatelli and Traorè. The caveat to this structure is when a back three is created, either through a midfielder dropping which signals the fullback to move wider, or Consigli holding the ball deep where he acts as a third centre back.

When Sassuolo consolidated but were initially pushed back, Locatelli would drop into the defence to allow Sassuolo’s fullback who was responsible for providing the central superiority in the build-up to stay forward which allowed the wingers to continue in the half-space where they could be more dangerous. This allowed for continued control of possession against Juventus front pressing two, as midfield support in deeper regions once Sassuolo had established themselves was rare.

This also generated time, space, and centrality for Locatelli, who much like Consigli could exploit Juventus compactness because of lack of pressure. This could generate a structure for 2nd balls/pass backs from Francesco Caputo as the two narrow wingers draw the fullbacks, freeing Sassuolo’s far side fullback to make a surging run from deep if they could be found. The overarching aim of: Consigli’s involvement, narrow fullbacks, and Locatelli dropping was central control to stretch the pitch.

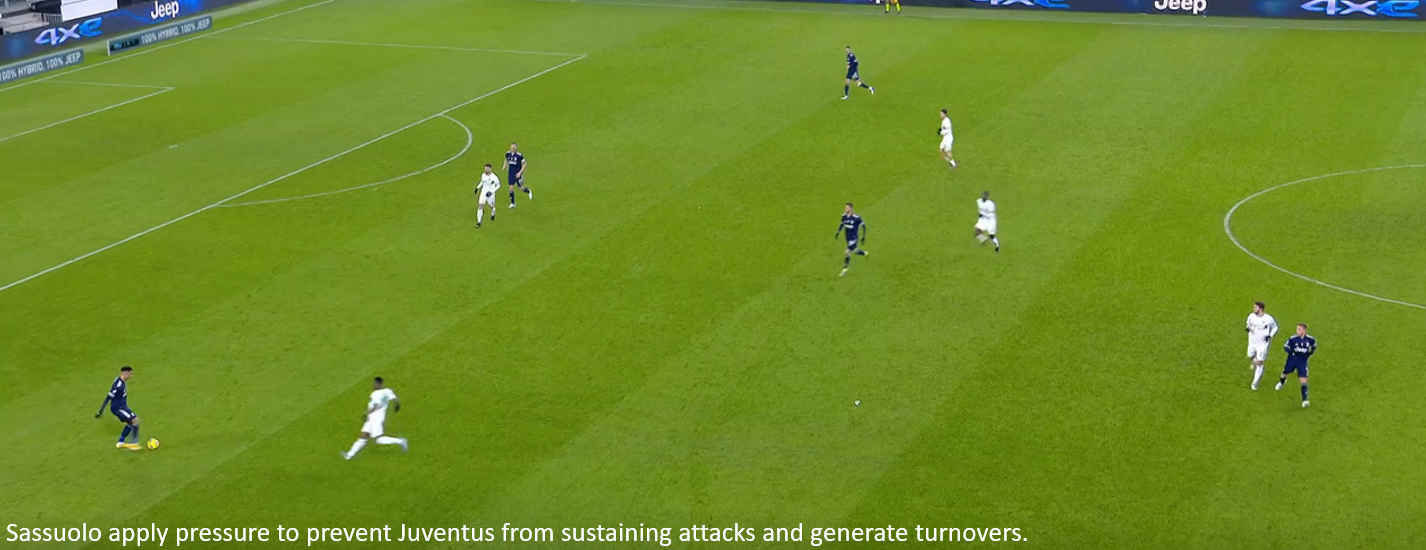

With regards to pressing a back pass from midfield to defence seemed to be the trigger for Sassuolo to apply pressure to the ball carrier and tightly mark potential direct recipients. This occurred in many stances including should they have pushed Juventus back from an attack.

This is as they could better generate numerically advantageous situations despite having poor pitch coverage as Juventus were still re-grouping from the backwards pass. In doing so, they prevented Juventus from sustaining periods of pressure through the centre back ball-recycling as they were inclined to make safe backwards passes because of the high degree of separation between the defensive and midfield line leaving them exposed to turnovers.

Another instance was second-line engagements which could trigger situations resembling that of failed attacks (close ball carrier with the nearest player, tightly mark nearby players) if the back pass were forced and thus provoke higher pressing efforts. To apply a principle, if Juventus had the numerical superiority, they would form a block (4-4-2/4-4-1-1) whereas if they could establish parity through quickly marking progressive options, they would press, with the two common situations being a failed attack or progression attempt from Juventus.

The reference point to pressure was the direction of the ball explaining why Sassuolo did not initially follow a dropping midfielder as the distance between potential passes was not long enough to generate the time required for an effective press. Another trigger was a sloppily hit pass, probably under the similar rationale that it generated time for the organisation of the pressing effort.

They were additionally quick to re-group if the pressing effort on the second line failed, allowing Juventus to establish themselves higher up to protect space, where a ‘new’ second line would be created as the dropping Juventus midfielders advanced which would then act as the trigger.

This means from consolidated situations such as from goal kicks, Sassuolo sought to engage on the second line as to not expose too much space and because in deeper regions centre backs are not as dangerous actors because of the difficulty associated with playing a killer ball from that depth compared to the half-way line where pressure on CB’s is required to maintain a high line.

However, because their scheme could result in them dropping into a passive 4-4-2 mid-block if Juventus could establish themselves via a numerical superiority after the initial second-line press, their compactness could be exposed as they no longer effectively protected the space in behind through pressure on the ball carrier.

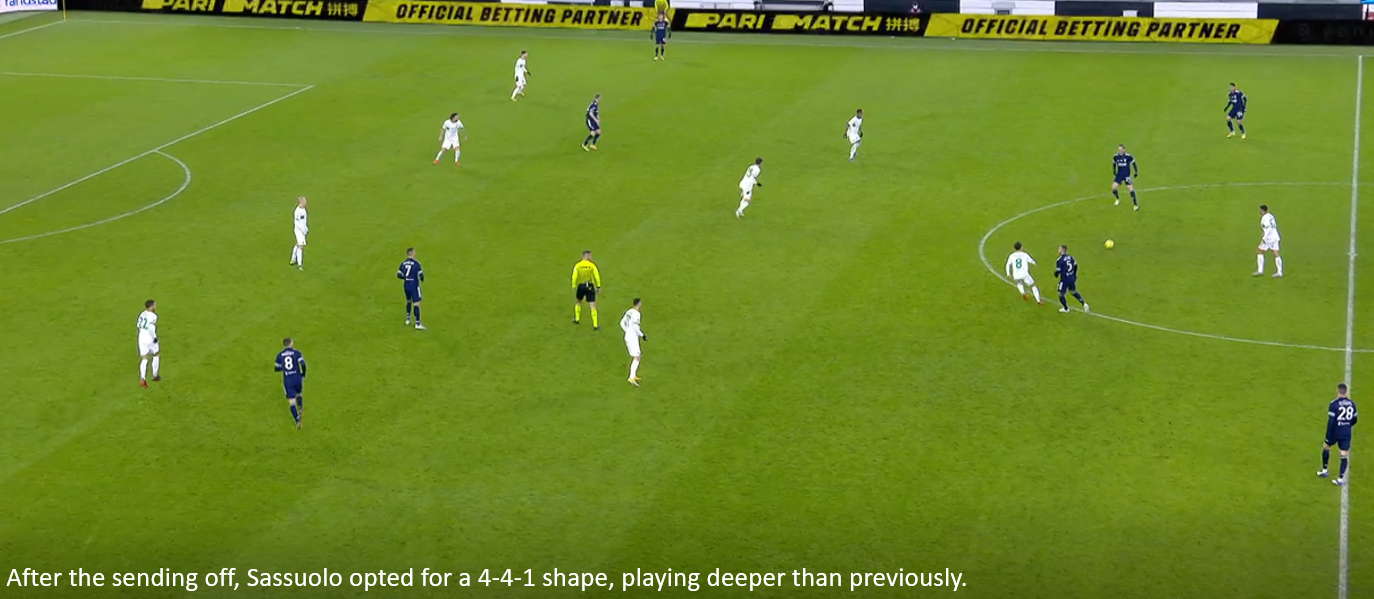

Pedro Obiang’s sending-off on the cusp of half-time seemed to have scuppered what was an extremely competitive and interesting game as Sassuolo initially struggled in the period between the sending off and half time.

Maxime Lopez and Jeremy Toljan were substituted on for Francesco Caputo and Filip Đuričić at half time, the two players most likely to be considered game-changers, with Mert Müldür advancing to right midfield and Grégoire Defrel becoming the centre forward. This created a 4-4-1 block off the ball, which sat deeper and played more passively as the pressure could not be applied to the centre backs to the same extent.

In possession, Sassuolo sought to take advantage of numerical superiorities which can still be achieved in deeper regions despite being a man down due to the necessity to protect space in addition to their willingness to involve Consigli.

This helped them establish a degree of control through limiting the pressure they sustained off the ball while serving as a tool to open space for quick transitions. The deeper commitment often meant they lacked players to capitalise upon space which placed emphasis on the individuals left in attack to craft chances with little support.

The goal, for instance, required Juventus incompetency in that they were far too passive in allowing Locatelli to progress, and Aaron Ramsey was out of position which is where Traorè smartly moved into which subsequently required a deft touch from Defrel to craft an opportunity. When playing with ten men it is imperative not to take unnecessary risks due to reduced cover which places greater emphasis on capitalising on the moments which do appear in the final third, often requiring some combination of individual spark and opposing errors.

This game was particularly interesting because it showed a side to Sassuolo which many do not associate with them which is the ability to remain in an organised and compact block against high-quality opposition. The issue is not lack of ability but rather lack of inclination as their strengths lie in their systematic build-up which favours possession as a tool for creating transitions.

They were at minimum equal with Juventus with 10 men and adapted well to circumstance, still looking promising and composed in possession. Juventus getting the result was probably fair upon reflection, however, that is to be expected. The result meant Sassuolo dropped to 7th while Juventus ascended the table to 4th, 7 points with a game in hand behind league leaders Milan.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / DeFodi Images