Tactical Analysis: Niko Kovač’s Monaco

After enduring a couple of dreadful seasons (2018/19 and 2019/20) where the club seemed to lose its stability, Monaco required structural changes to regain its status. Hence, hiring Paul Mitchell as the sporting director before the start of the current season was the first step. It was followed by hiring Niko Kovač, the former Bayern Munich and Eintracht Frankfurt manager.

Both these appointments seem to have had a significant impact as the eight-time Ligue 1 champions currently sit at fourth position, merely four points behind the league leaders and well within the reach to qualify for the Champions League next season. Bolstered by a treasure trove of young talents such as Aurélien Tchouaméni, Sofiane Diop and Caio Henrique, Monaco are chasing their first league title since 2017.

The Monégasques not only have one of the most talented young squads but also play an attractive blend of attacking football, that involves the modern positional play principles. In this analysis, we will delve deep into Kovač’s attacking and defending tactics that have made his team so impressive.

Build-up Phase

Throughout the season, Kovač has used multiple formations like 4-3-3, 4-4-1-1, 4-2-3-1, 4-4-2, and 3-4-3, the latter two being the most significant ones. Having said that, Monaco plays with specific principles regardless of the formation.

Kovač puts a lot of emphasis on the positional play during all the phases of the game. Naturally, he likes his teams to play out from the back in the first phase. The buildup shape has adequate width and depth as the players look to occupy all the vertical and horizontal lanes. Besides, they ensure numerical superiority in their half which aids a swift buildup and vertical progression.

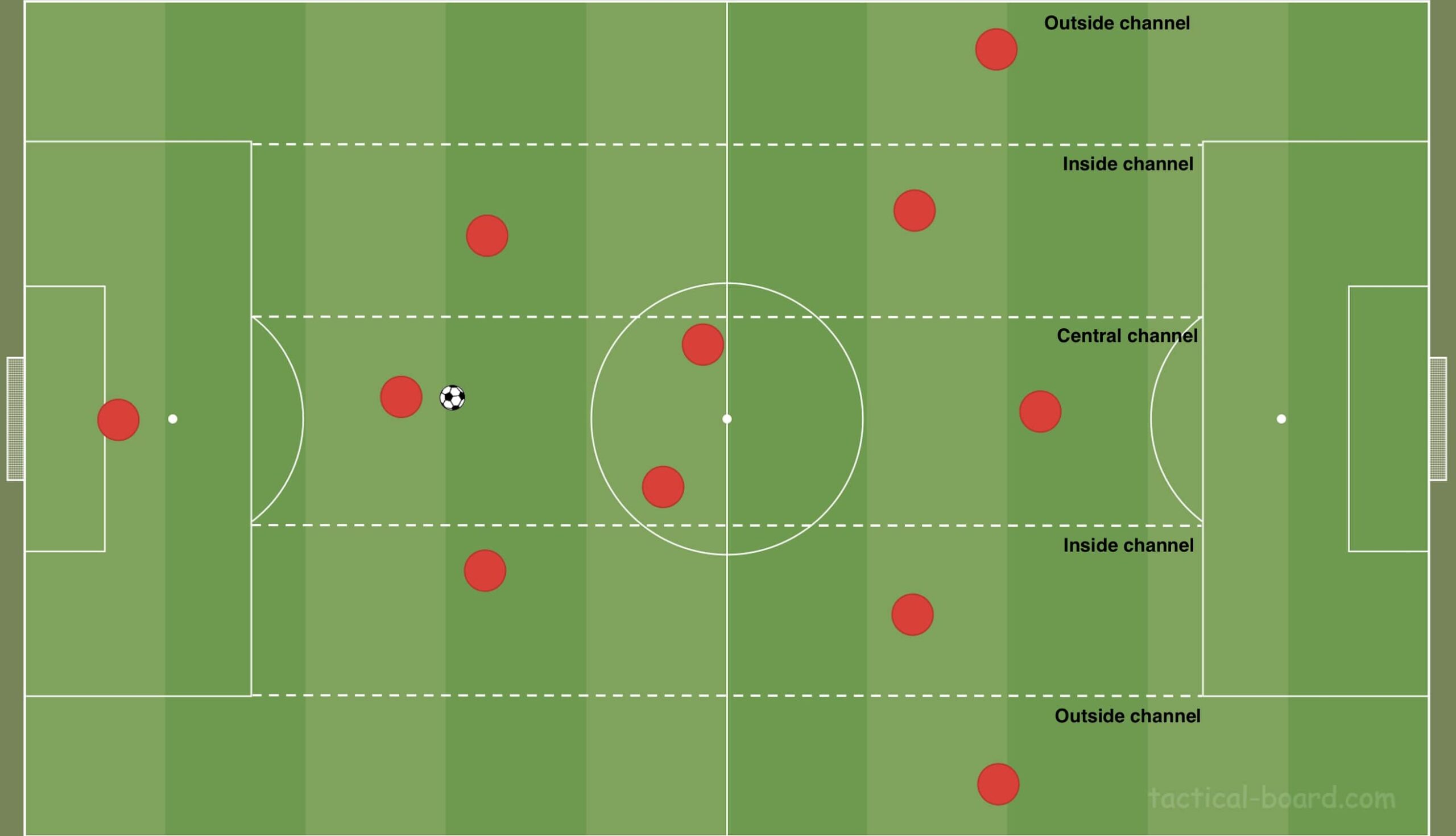

Monaco use two different buildup shapes based on opposition and its pressing tactics. One of them is a 3-2-4-1, which is shown in the figure below. This shape is used in games where Monaco are favored to have most of the ball as a result of the opposition’s reluctance to press high and rather maintain a compact defensive block without the ball.

As you can see in the figure, there are no more than three players in a single horizontal line and no more than two players in a single vertical line. This kind of positioning results in optimal use of all the vertical corridors to achieve positional play.

The central defender stays slightly deeper to act as a sweeper and facilitate swift distribution, while the remaining centre-backs push wide into the half-spaces. The wingbacks push high and hug the touchline to provide the width. The defensive midfielders stay central, but they often stagger and make lateral movements to create and receive possession in space. Finally, the striker provides the depth and stays central while the remaining two attackers drop into the half-spaces.

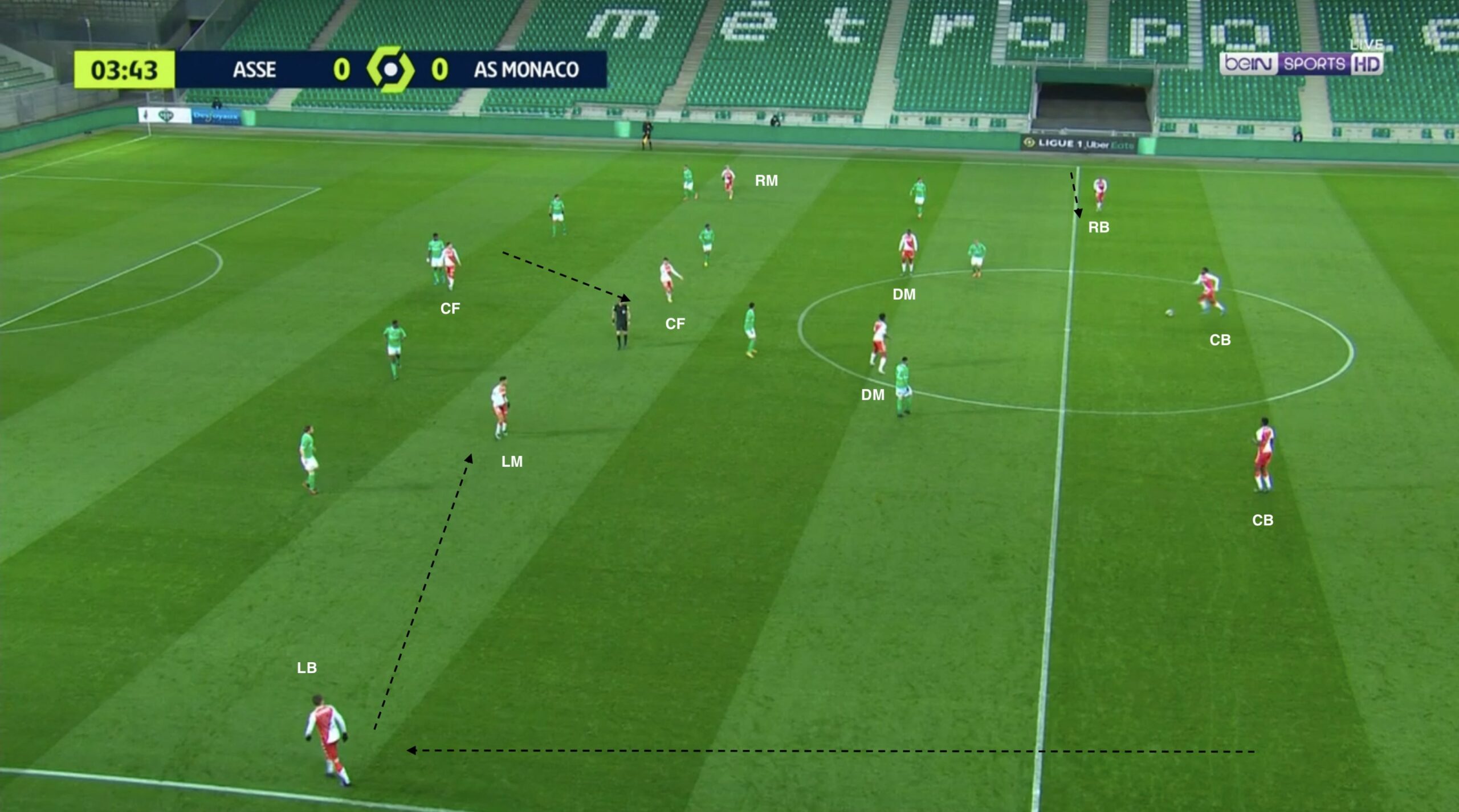

The 3-4-3 system naturally allows the team to be in the desired shape. However, when Monaco are set up in 4-4-2, it involves some level of movements and rotations, especially in the wider areas, to achieve the desired shape. The following figure shows Monaco’s on-paper 4-4-2 formation that has transitioned into a 3-2-4-1 shape during the first phase.

While the left-sided fullback continues to provide width on that side, the width on the right is provided by the right-winger rather than the right full-back. Hence, the right-fullback stays deep and tucks into the half-space to form the three-chains of centre-backs while the left-winger pushes into the left half-space higher up the field. The remaining half-space (right) is occupied by one of the strikers, who drop deep.

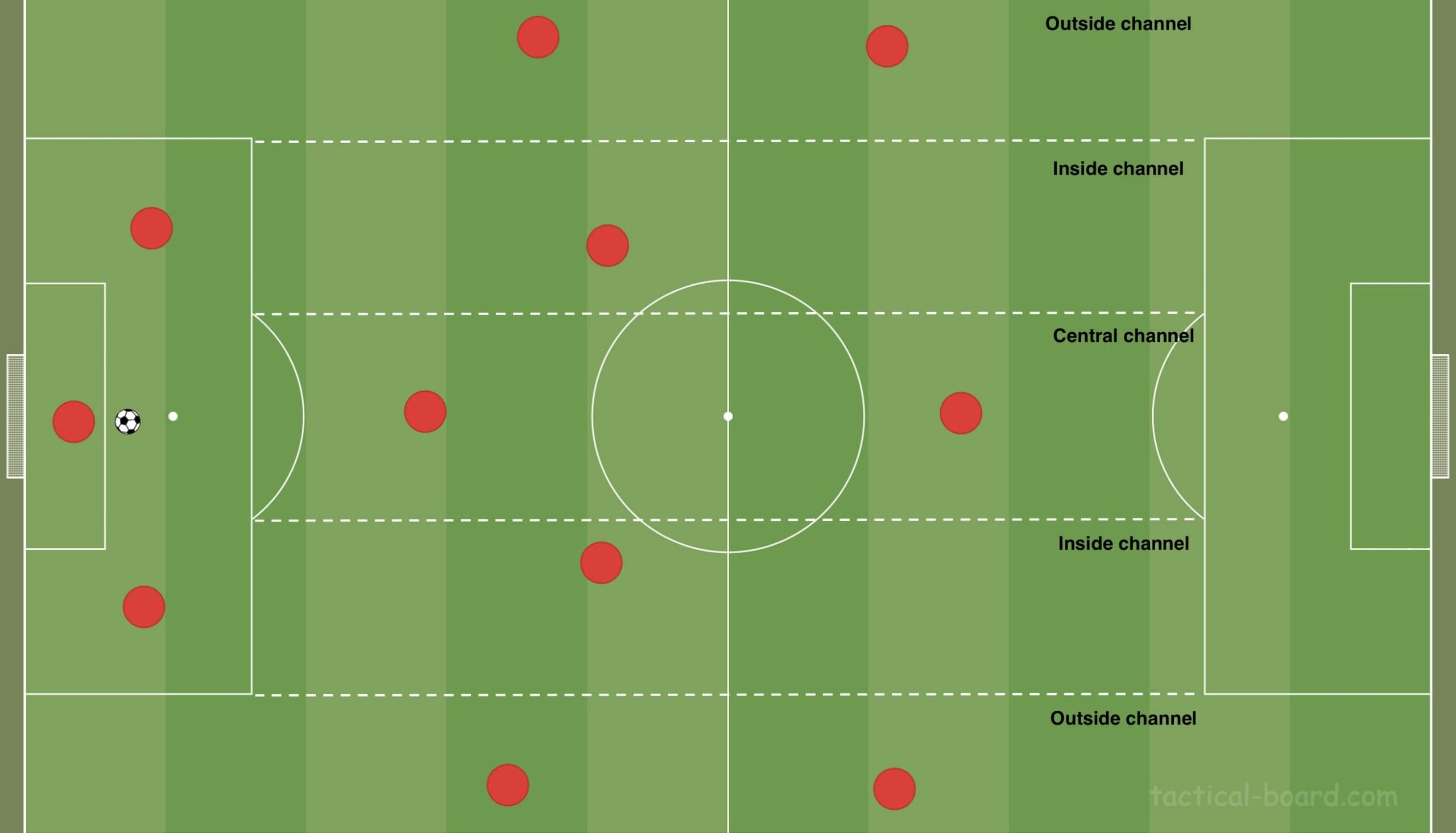

Alternatively, Monaco builds with a 2-1-4-3 shape in the remaining games where an opposition likes to press high. The desired shape is shown in the figure below.

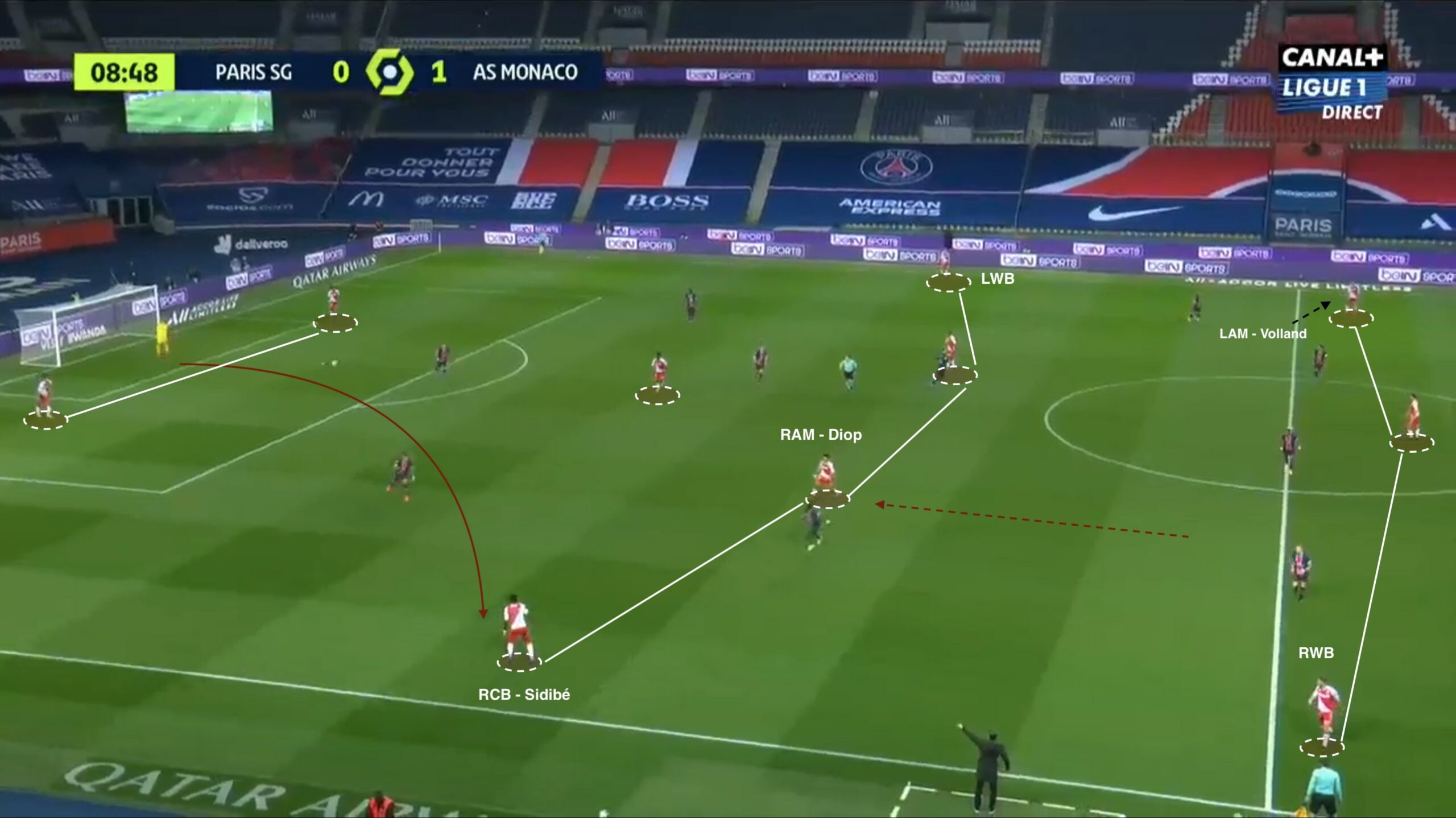

Kovač looks to force the opposition to stay central while ensuring a free man on either flank through which his team would progress from the first phase. This involves the creation of width and numerical superiority in the defensive half, which is achieved through the positional rotations of the players. Primarily, one of the centre-backs pushes wide and one of the half-space attackers drops deep, as shown in the following figure.

Paris Saint-Germain have committed six players higher up the field in their 4-2-3-1 pressing shape. Observe that the dropping of an extra attacker (Diop) not only allows Monaco to achieve the 7v6 numerical advantage in their half but also forces PSG to stay compact in their press which in turn keeps Monaco’s wide defenders in space.

The goalkeeper plays a vital role in this shape as he is tasked to find the free wide man who can progress the ball. As Benjamin Lecomte finds Djibril Sidibé, it isolates Idrissa Gana Gueye two versus one. If the PSG midfielder presses Sidibé, the defender can look for nearby passing options. Alternatively, the defender can drive with the ball in the space ahead of him.

Vertical Progression

Kovač was labeled as a defensive coach in his previous stint with Bayern Munich. However, he likes his Monaco team to play attacking football which is evident from the fact that the Monégasques has scored 60 goals so far in Ligue 1, only less than PSG. Monaco continues to achieve the positional play in the higher thirds. Besides, they have multiple alternatives to achieve penetration which enables them to find solutions against most of the opposition defense.

Positional Play 1 – Space Between the Lines & Multiple Penetration Options

One of the ways that Kovač’s men progress the ball is to find an attacker between the opposition’s defensive and midfield lines. The defensive midfielders and wide central defenders are trained to make smart passes by breaking the opposition’s central lines.

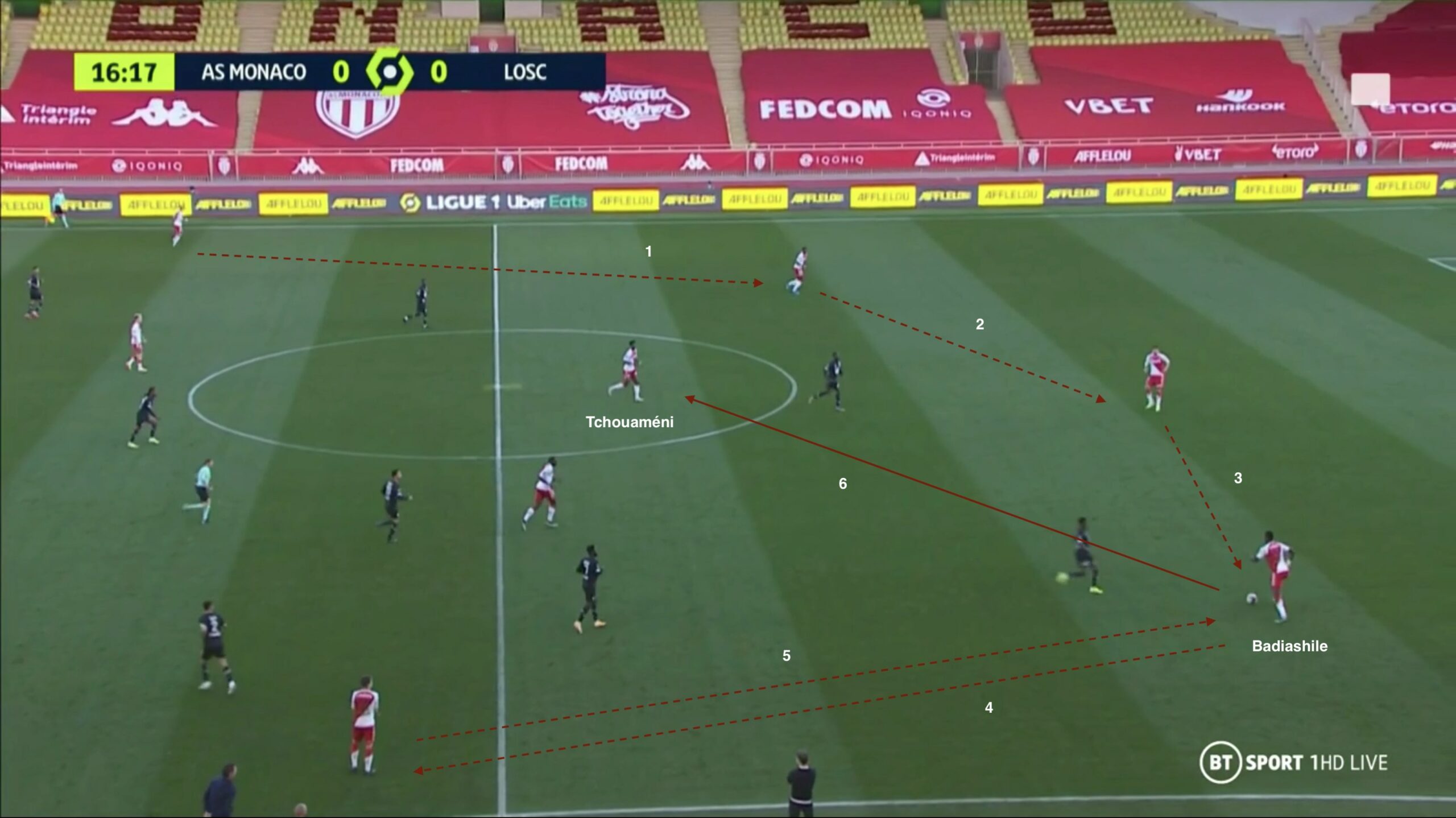

With the numerical advantage against the opposition’s initial line of pressure, Monaco patiently rotates possession from one side of the field to the other (U-passing pattern) to maneuver the opposition pressing lines until space is created for one of them to make the line breaking pass. The ball-sided wingbacks keep dropping deep to provide the passing support.

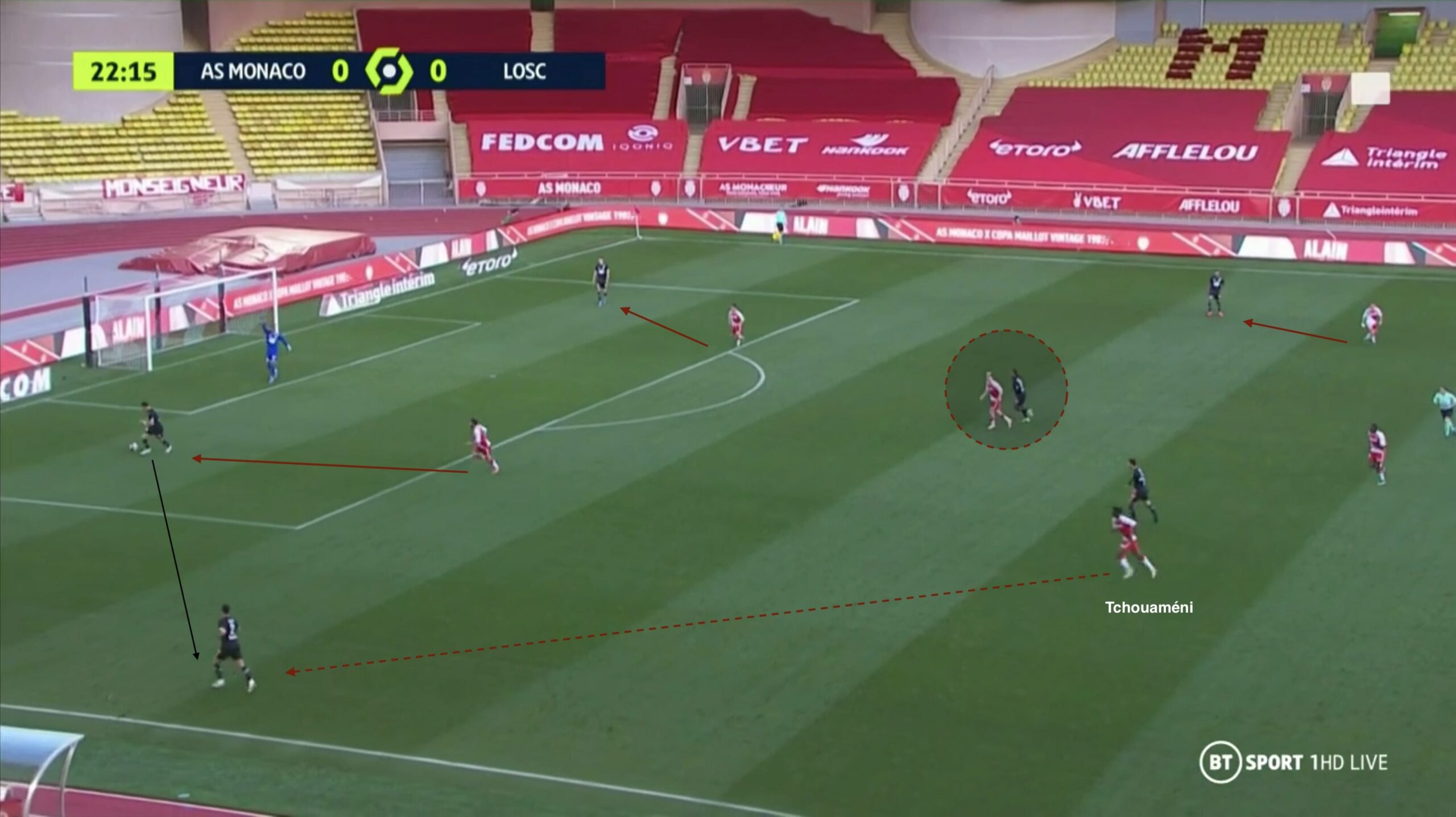

The figure above shows the U passing pattern starting from the right wingback and ending with a pass to the left centre-back Benoît Badiashile. It not only split the Lille’s strikers to create lateral space between them but also created vertical space between Lille’s lines. Consequently, it opened up the passing option for Badiashile towards Tchouaméni in the space.

As Lille’s midfield lines pushed up to press Tchouaméni, it expanded the vertical space between their defensive and midfield lines. Tchouaméni was able to receive, turn, and break central lines to find Aleksandr Golovin, who dropped between the lines into the half-space.

The central midfielders play a crucial role when Monaco looks to achieve penetration in this manner. While their off-the-ball movements and staggering help them to receive possession in space and time to make a turn, their technical skills help to achieve penetration. In Tchouaméni and Youssouf Fofana, Kovač has a pair who he can trust due to their excellent ability with the ball. The French duo has made a combined 10.43 progressive passes and 9.87 passes into the final third per 90 minutes so far which demonstrates their importance in ball progression.

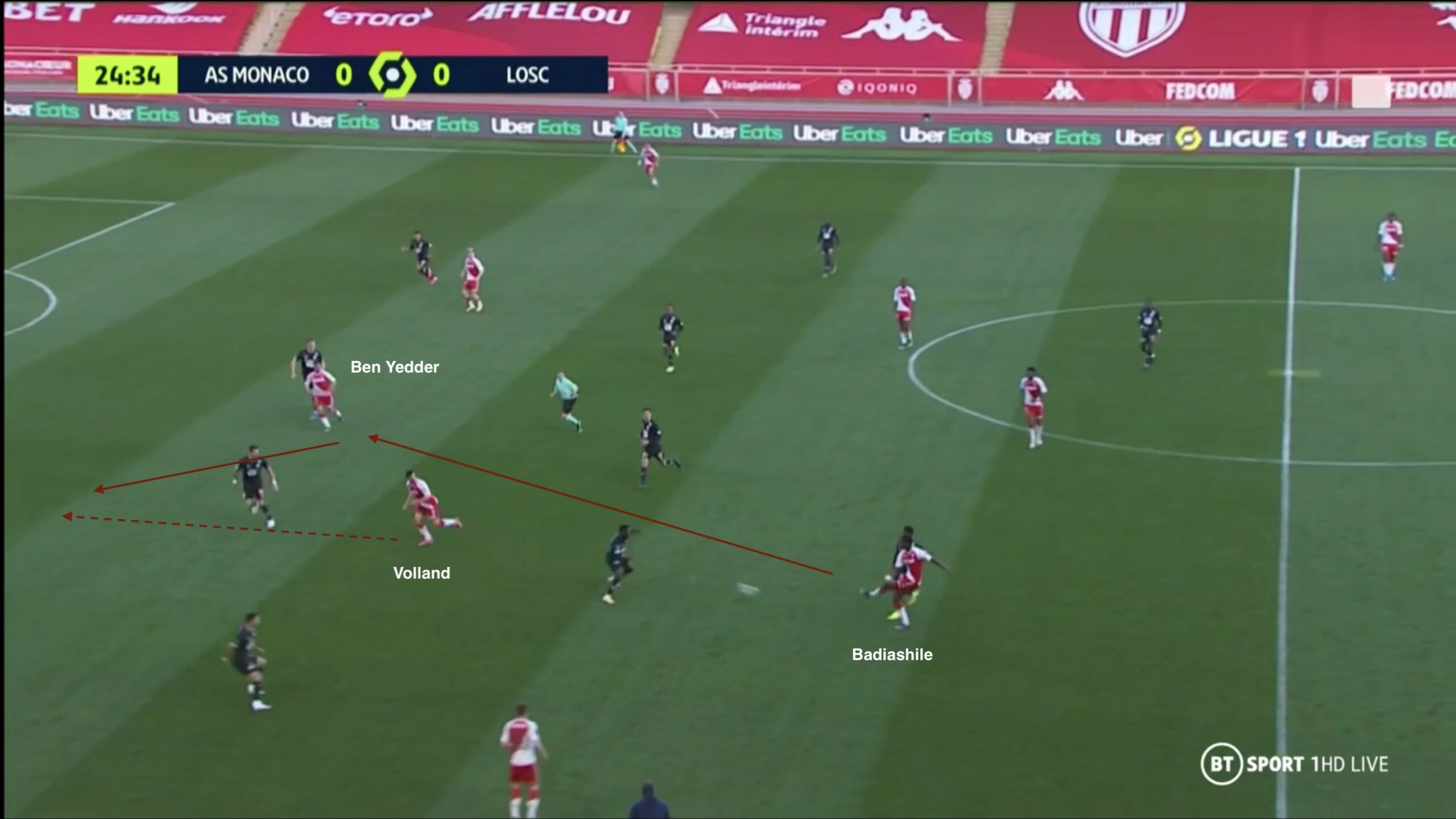

Monaco’s strong build-up foundations do not rely only on the central midfielders. In situations when they become inaccessible, the wide centre-backs are also adept in providing verticality. Badiashile and Sidibé have combined to make 9.59 progressive passes and 10.31 attacking third passes per 90 minutes. These are impressive numbers for a pair of centre-backs. The following figure shows how Badiashile provided penetrating pass to Wissam Ben Yedder, who released Kevin Volland beyond Lille’s backline.

The attacking trio provides an excellent presence between the lines. They tend to make opposite movements as one of them drops deep while the others make runs in behind the backline. Moreover, the attackers alternate their dropping movements which makes their attack much more fluid and help to unbalance an opposition defensive line.

Furthermore, this allows Monaco to have multiple goal-scoring threats. Indeed, Monaco’s striking pair of Ben Yedder and Volland share a goal tally of 13 goals each. The third attacker is generally Diop/ Golovin, whose combined goal tally is 11.

When an attacker is allowed to receive possession between the lines and turn, he has multiple channels enter the final third. He can either look to release the wingback on the outside space or either of the two attackers behind the backline. In most cases, the compactness of the opposition’s defensive line forces the man in possession to go towards the near flank to create a crossing situation which is why Monaco has made 21 crosses per game, only behind Rennes’ 22.

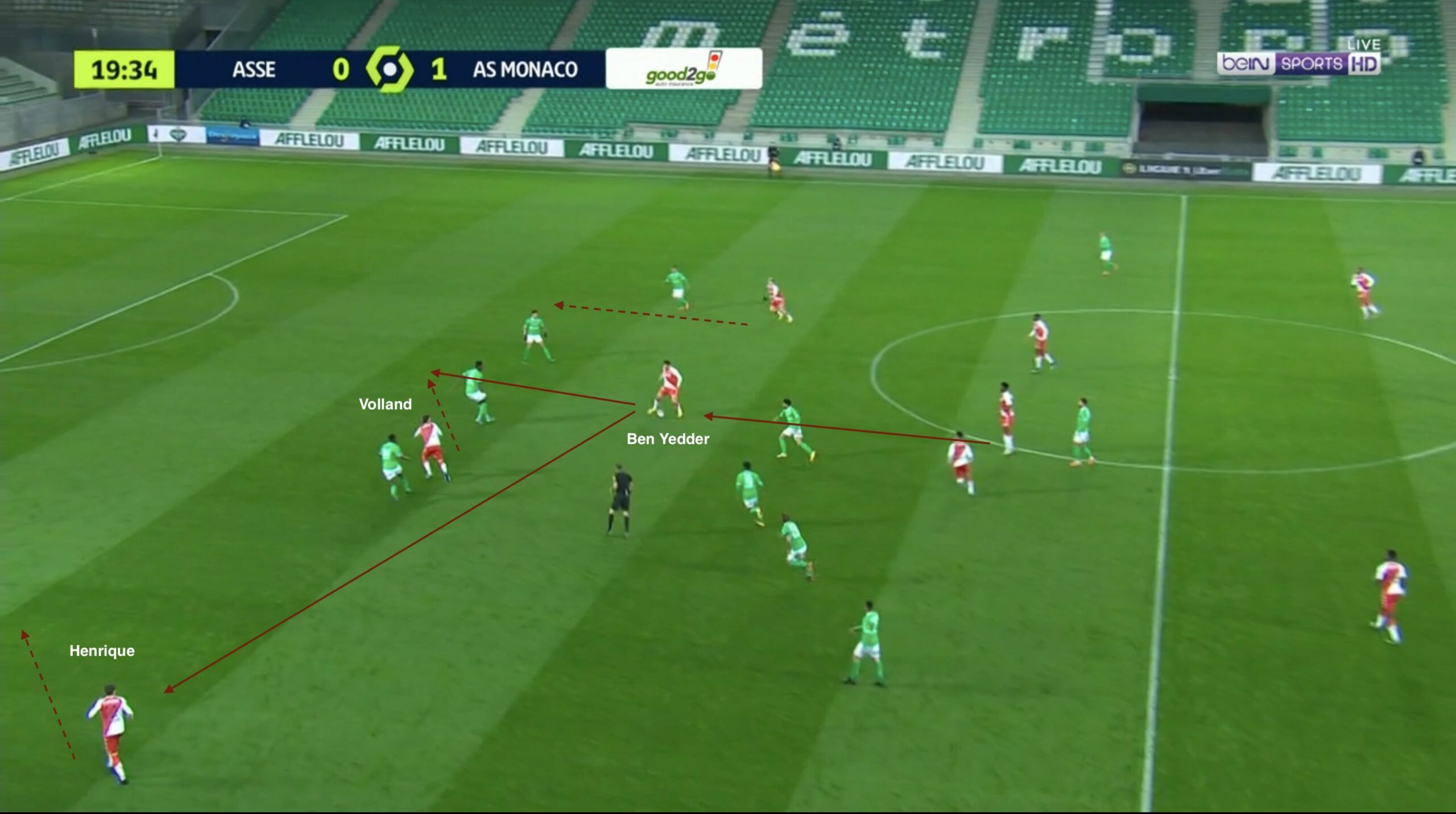

The following figure shows that as Ben Yedder receives the ball between the lines, he has the option to release either Volland behind Saint-Étienne’s backline or Henrique on the left.

Positional Play 2 – Switch of Play

Another method of vertical ball progression used by Monaco is constantly changing the point of attack towards the underloaded side where the wide receiver can be isolated in space. The Monégasques make 17.6 switches per 90 minutes, only less than Strasbourg. It not only assists in breaking down low defensive blocks, but it is also effective against high defensive lines.

As you can see in the figure above, Saint-Étienne’s ball-oriented low block prevents Monaco from any chance of central penetration. However, Kovač’s men have managed to shift the defensive block of the men in green towards the right with a series of short passes and Diop’s inside movement that has dragged the Saint-Étienne fullback towards the center. Observe Henrique’s marauding run on the left as Tchouaméni’s long ball released the wingback in the wide channel with ample space ahead of him to make a cross inside the box.

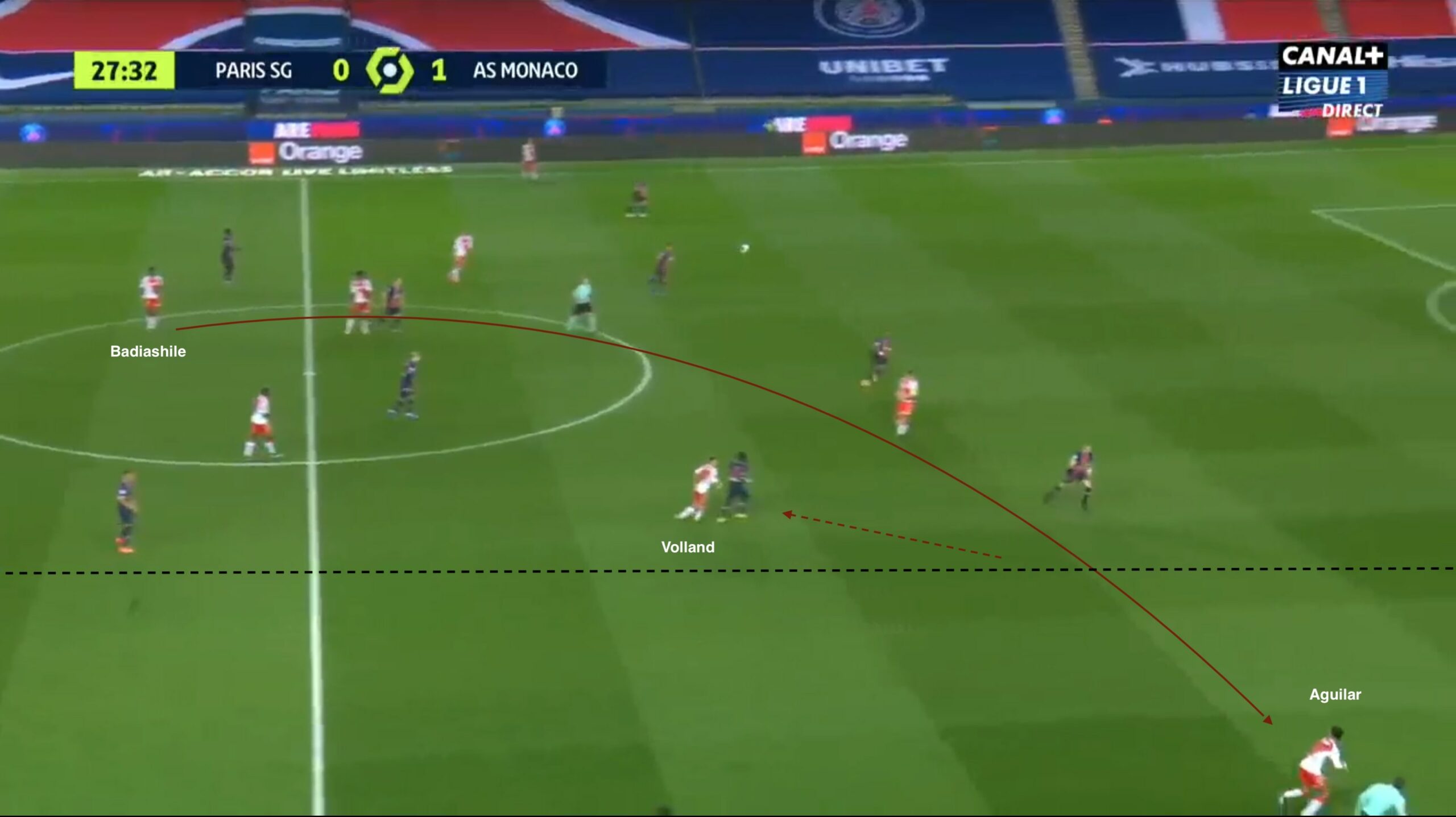

In contrast to the figure above, consider the following figure where PSG have maintained a high defensive line. Once again, Monaco dragged the opposition on the left side while Volland made an inside movement to create space for Ruben Aguilar on the flanks. With time on the ball, Badiashile quickly released Aguilar on the outside with space in front of the wingback.

Positional Play 3 – Overloading the Flanks and Releasing into the Channels

The wide players of Monaco generally hug the touchline which helps them to stretch the opposition defense horizontally and create space into the channels. The Monégasques then look to overload the flank through the run of the near-sided attacker and isolate the opposition fullback 2v1. If the wide player receives time, he will look to release the attacker into the channel.

As you can see in the figure above, as Krépin Diatta receives the ball high and wide, the Nantes fullback was slightly late in pressing the wingback. This allowed Diatta to release Volland into the channel. Observe that Diop’s central movement has forced the remaining three centre-backs of Nantes to stay central, thereby creating space into the right channel. This tactic is particularly useful against oppositions that play with a backline of four. An extra defender in a five-at-the-back system may prevent Monaco to overload the flank.

Defensive Principles

Kovač started his managerial career at Red Bull Salzburg, a club owned by Red Bull that is known to have a distinct style of play that incorporates a high pressing system. Hence, it comes as no surprise that his Monaco side “defends from the front,” which means they like to press the oppositions higher up the pitch in a bid to win the ball early and possibly in dangerous areas. Monaco has a PPDA of 8.71 this season, which means they allow the opposition to make only under nine passes before making a defensive action. Only PSG press more aggressively than Monaco in Ligue 1.

During an opposition build-up, Kovač instructs his side to press high in a 4-2-4 shape. The man-oriented zonal marking shape is compact, which forces the opposition to guide into the wide areas. Once the ball is played into a flank, Monaco’s ball-side player quickly initiates the press while the players around him move towards the ball side and cut all the short passing options to force the man in possession to either play a long ball or force a turnover in the defensive third.

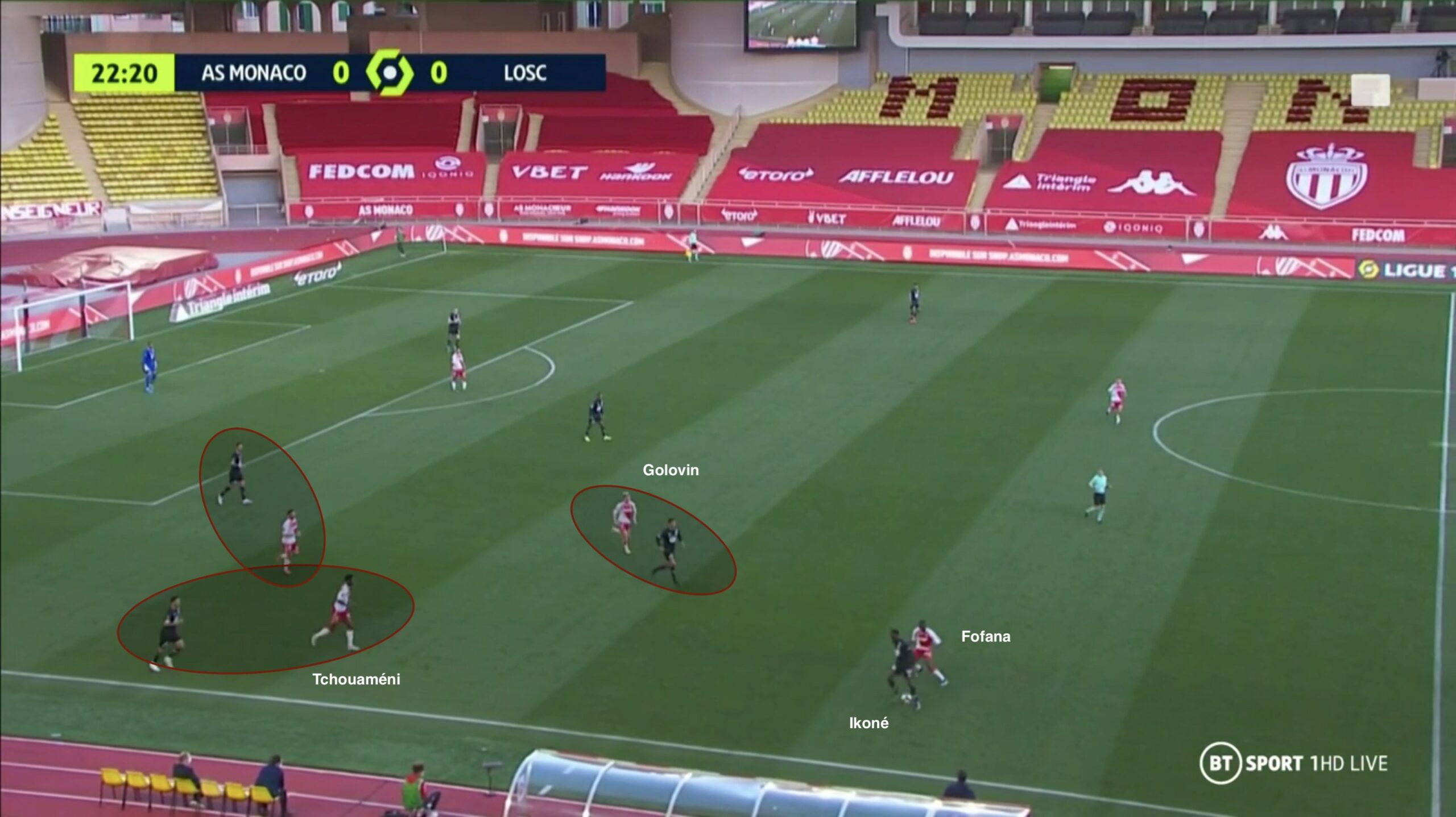

As you can see in the above snapshot, Monaco’s attacking quartet is man-marking Lille’s four defensive players, forcing them to guide the ball towards the right fullback, who is kept in the space. As the ball is distributed to the full-back, Tchouaméni quickly sprints to close him down while keeping the CM in cover-shadow.

Tchouaméni was slightly late in this instance which allowed the Lille full-back to advance the ball higher towards Jonathan Ikoné, who dropped deep. Observe that Golovin and Fofana drifted towards the ball to mark all the nearby players. Hence, Monaco eliminate all short passing options and pin Lille on the flanks.

One of the advantages of showing the opposition towards a flank is that Monaco can press with fewer numbers in the opposition half as a switch of play goes out of the equation. It further allows them to secure the defense by having more bodies at the back.

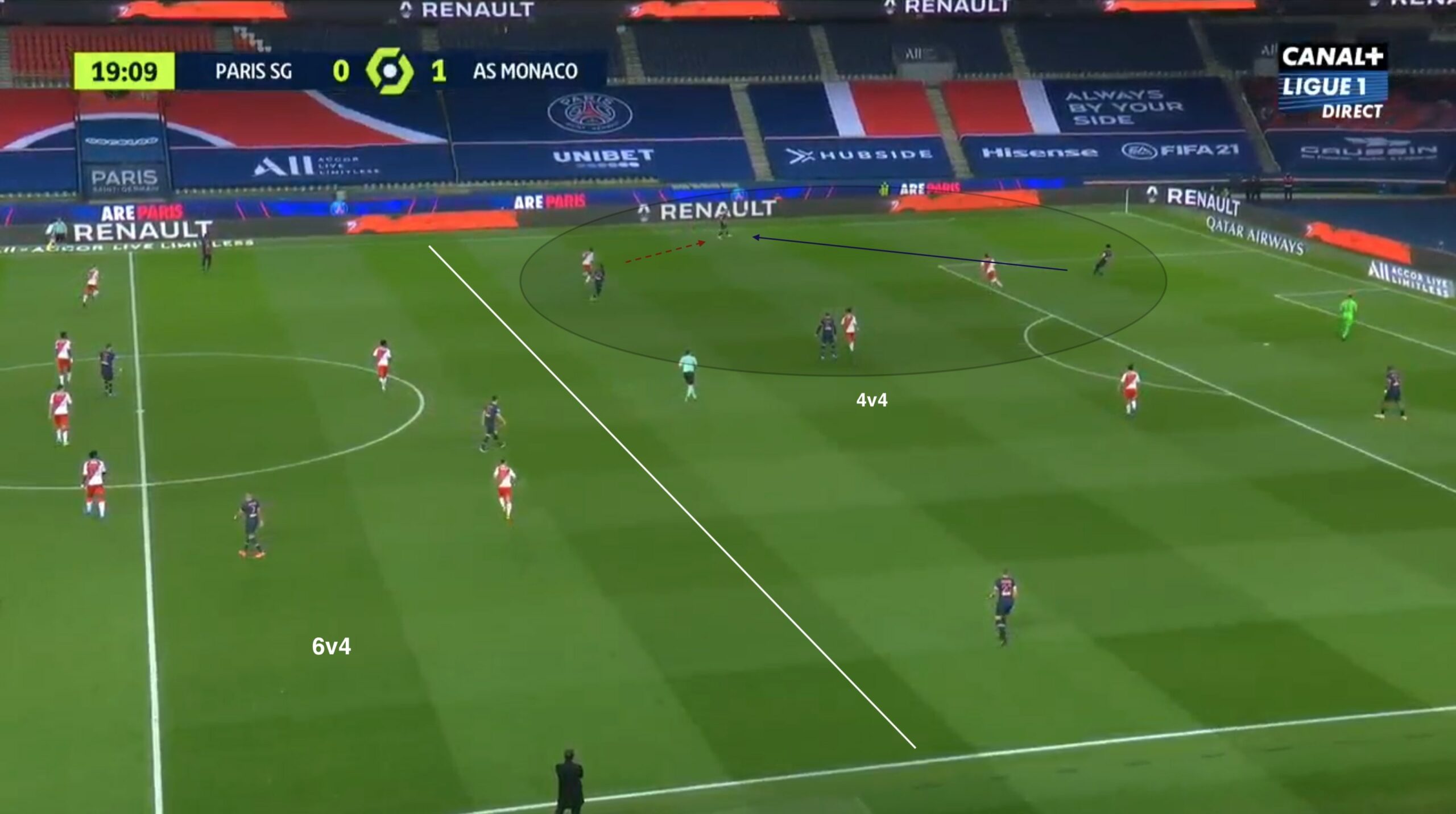

In the following figure, as PSG plays towards the right full-back, six of their players were pinned by only four Monaco players in the defensive third. Consequently, Monaco had a 6v4 advantage at the back. Besides, observe Monaco’s 4-2-4 pressing shape.

Kovač also instructs his side to counter-press if they lose the possession in the opposition third, which is why Monaco are involved in a lot of defensive duels higher up the pitch. Monaco have made 22.9 tackles per 90 minutes, out of which 56.5% of them have been in the attacking and middle thirds. The Monégasques lead all the Ligue 1 clubs in both these metrics.

Besides, they have gained possession within five seconds of applying pressure 44.9 times per 90 minutes, only behind Angers and Saint-Étienne. All these stats demonstrate the pressing and counter-pressing tendencies of Monaco under the German manager. When the opposition breaks Monaco’s high press, Kovač’s men transition from a 4-2-4 into a mid to low block of 4-4-2. The first two defensive lines stay compact as they tend to force the opposition wide, as shown in the following figure.

Set-Pieces

Monaco have scored 18 goals in set-pieces, which is highest not only in Ligue 1 but also amongst all the clubs in Europe’s top five leagues. It also constitutes around 35% of their total non-penalty goals, which is a significant portion. Kovač’s coaching staff has created a simple but unique corner routine tactic which can be analyzed in detail as a separate article but here, we will go over their basic strategy in corner kicks.

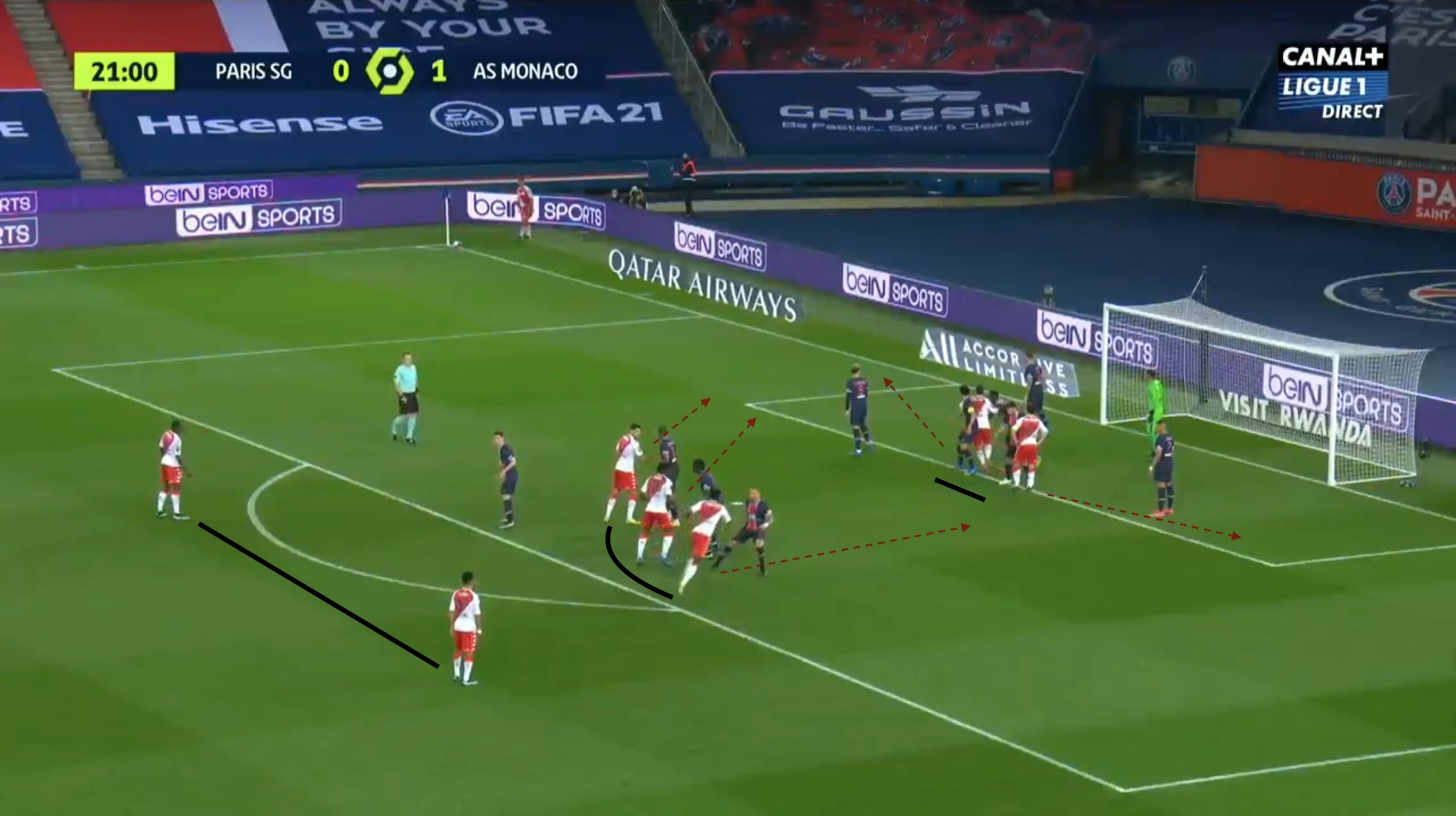

Their initial shape during a corner is 2-3-2, as shown in the image above. The two strikers, commonly Volland and Ben Yedder, stay inside the 6-yard-box. These two strikers are relatively short in height, so their role is not to win headers but to create space around the opposition goalkeeper. The next line is made up of Monaco’s three tallest players on the field, who ideally are the central defenders: Badiashile (1.94 m.), Axel Disasi (1.9 m.), and Guillermo Maripán (1.93 m).

Tchouaméni (1.85 m.) is chosen in absence of a centre-back. The onus on scoring headers lies on one of these players. Observe the wide distance between these two lines. It is the subtle movements of these five players that hold the key to Monaco’s corner routines. These movements are highlighted in the figure above. The final line of two stays slightly outside the penalty box to prevent the opposition’s counterattack or take a long-range shot.

As the ball is kicked, the two strikers, who are marked by two PSG players each, make movements towards the opposite posts, dragging their markers away from the front of the goal. Two of the three players from the second line move towards the near post, in turn dragging their markers away from the front of the goal as well. The combination of these movements provides maximum coverage of the six-yard box to Monaco’s heading target. Observe the clear heading path and target that Disasi has as a result of the movements of the other players around him.

Defensive Frailties

Monaco’s tendency to press with a high line of engagement means the defensive line stays higher to maintain the vertical compactness. Oppositions can take an advantage of this high backline to send the balls in-behind the Monaco defenders.

Instead of playing out from the back against Monaco’s high press, Montpellier used the direct approach and constantly created overloads against Monaco’s backline of four. It allowed The Paillade to isolate the Monaco full backs 2v1, as shown in the figure. The Montpellier goalkeeper directed his kicks into the half-space for a free man who would look to interplay with adjacent teammates to release a striker in-behind the Monaco backline. In the figure, the goal kick found Jordan Ferri, who was able to control the ball and release Andy Delort behind Badiashile.

Monaco have conceded 38 goals so far in Ligue 1, which is higher than seven other teams. A significant portion of those goals has been due to individual errors in the deeper areas. The average of Monaco’s most frequently used centre-backs and defensive midfielders, who are largely responsible for doing the defensive work, have is 22.5. Hence, it is only natural for them to make mistakes in dangerous positions and concede goals.

The figure above demonstrates an example against Marseille where Monaco’s two errors in the defensive third led to a 2-1 defeat against their rivals. Henrique tried to dribble past Valentin Rongier in the defensive third against Marseille’s high press. He took an extra touch which forced a turnover and Marseille was able to score.

Conclusion

Monaco’s young talents and tactical setup make them one of the interesting teams to watch in Europe. Niko Kovač and his staff deserve credit for successfully implementing positional play principles with a squad that is third youngest in Ligue 1 with an average age of 24.5. The inexperience in that defensive group tells us why they had kept only five clean sheets in the first 25 league games.

Having said that, four clean sheets in the last five games highlight significant improvement. On the other end, the variations in their attack and set pieces make them a threat against any defense and have been notable reasons for making them a contender for a Champions League spot, but also to win the Ligue 1.

By: Mayur Mehta

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Agence Nice Presse / Icon Sport