Tactical Observations: Villarreal CF Under Quique Setién (Part 2)

In the second half of this two-part series, delving into some of the key and recurring tactical tendencies of Villarreal under Quique Setién, we will cover the Yellow Submarine out of possession. Part 1 of this article focussed on Villarreal with the ball. As a reminder, for this piece, the following LaLiga games were observed.

Villarreal 1-0 Girona, 22/01/2023

Villarreal 0-1 FC Barcelona, 12/02/2023

Villarreal 1-1 Real Betis, 12/03/2023

Osasuna 0-3 Villarreal, 19/03/2023

Villarreal 2-0 Real Sociedad, 02/04/2023

Real Madrid 2-3 Villarreal, 08/04/2023

Villarreal 1-2 Valladolid, 15/04/2023

Sevilla 2-1 Villarreal, 23/04/2023

Villarreal 4-2 Espanyol, 27/04/2023

Girona 1-2 Villarreal, 20/05/2023

Rayo Vallecano 2-1 Villarreal, 28/05/2023

Out of Possession

Without the ball, Villarreal had a number of recurring principles in different phases of play. Their out-of-possession shape would adjust through the different thirds of the pitch and sometimes vary subtly from game to game, and even during games, in some instances.

To begin to explain what Villarreal do without the ball, it is probably best to start in the middle of the pitch. When the opposition had settled possession in front of the Yellow Submarine or had bypassed their first line of defence, their most typical defensive set-up was 4-1-4-1 or some slight variation of that, think 4-4-2 or even 4-4-1-1 on occasions.

It is important to note, however, that these formations are merely a reference point to help set the scene, as Villarreal were rarely in these ‘defined structures’ for too long, which will be expanded upon further shortly. But before that, see Figures 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d below to help visualise these typical starting mid-block shapes.

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Figure 1c

Figure 1d

A few observations to note on the visuals above are;

- For reference, Dani Parejo is the (-1-) situated between the midfield and defensive lines (except for the away game against Girona where he was suspended)

- The height of the defensive (last) line, which is always in or around the centre circle to maintain team compactness and ensure a defender is in close proximity to jump up to any opponent in between-the-lines

- About a second or so after these screenshots were taken, either a Villarreal midfielder or defender jumped to engage the ball or track an opponent resulting in these starting mid-blocks to resemble a whole different ‘structure’ all together

Some readers may have also observed that in these four specific screenshots, Villarreal look at the risk of passes in behind their high last line due to a lack of pressure on the ball. However, fear not there were plans for this, as per observation point 3 above, an unopposed opposition central defender progressing with the ball would be a trigger for the ball-sided Villarreal central midfield to jump up and engage. Or, failing that, if an advanced opposition attacking player was found with a forwards pass, a Villarreal defender would be in immediate proximity to engage from behind (as per observation point 2 above).

As mentioned earlier in this article, Villarreal rarely stayed in any mid-block ‘defined structure’ for too long. And one of the main reasons for this was there were a number of triggers that would initiate their mid-block to become a mid-press, as per the already highlighted unopposed opposition central defender progressing with the ball.

To help depict some of these triggers, let’s look at some visuals. Figure 2a below is three seconds after the Figure 1d example above, and shows Alex Baena jumping up from the midfield line to engage the unopposed Girona central defender progressing with the ball – the aforementioned trigger. Baena purposefully curved his pressing run to ensure the Girona midfielder he was initially marking is now in his cover shadow and therefore not a viable passing option.

Figure 2a

In addition to Baena’s movement, notice how other Villarreal players are also on the move in the visual above. Étienne Capoue is jumping from his position behind the midfield line to cover the area and opponent Baena has vacated, Jorge Cuenca (the left-sided central defender) has jumped to help cover the Girona player between-the-lines, and Yéremi Pino is on his toes so he’s ready to get out to the Girona right fullback, but not too soon, as he wants to entice this horizontal pass as opposed to a vertical pass into the Girona player on his inside (which Cuenca is covering).

In Figure 2b below, the action picks up following the inevitable pass to the Girona right fullback whose body shape is not conducive here to receiving and then making a forward pass, another trigger. So he is immediately pressurised by Pino, and with no return pass (Baena preventing that) or inside pass (Capoue preventing that) he is forced backwards to his goalkeeper, another trigger.

Figure 2b

A final observation to make on the visual above is how the aforementioned players are now all 6-12 yards higher up the pitch (excuse the rough calculation of using the pitch gradients as counters) and as a result of this territorial gain, the Villarreal players on the ball-far side are getting ready to initiate the team’s high block – see Nicolas Jackson and Ramón Terrats beginning to move towards their nearby Girona opponent. (For those interested, the conclusion of this passage of play involved some initial short passes from Girona inside their box under pressure, before the Girona goalkeeper kicked long and Villarreal (temporarily) regained possession in their backline. Mission complete).

So in this single example, Villarreal executed a number of their mid-press triggers that were common across all of their observed matches. To recap, these included an unopposed central defender progressing with the ball (the same would happen if a midfielder dropped into the backline and began to carry forward), a suboptimal body orientation of an opponent e.g. facing towards their own goal, and a backwards pass. All pretty standard triggers across football, but triggers nonetheless that Villarreal invariably react to.

Another reason why Villarreal’s mid-block remained dynamic was certain players having specific individual roles against certain opposition. The most common occurrence of this was Samuel Chukwueze dropping deeper on the right wing to cover an advanced left fullback or left wingback, therefore making the Villarreal midfield line lopsided / staggered. (Note – whilst the Nigerian attacker proved on multiple occasions that he’s willing to perform such tasks for his team, his effectiveness in doing so is probably worth more in-depth individual analysis).

So to summarise this out-of-possession phase, whether in a mid-block or mid-press, some of Villarreal’s recurring tendencies were trying to maintain relative compactness from front-to-back and being flexible and interchangeable with their organisation and in between their defensive lines. One of the benefits of the initial 4-1-4-1 starting shape was that it could easily transition into a 4-4-2 with two jumps (following specific triggers) as seen in the visuals provided above.

(Hopefully) now that you have a clearer picture of how Villarreal set up out of possession in the middle third of the pitch, let’s move up into the opposition’s own third and onto the Yellow Submarine’s high block and high press, where the themes of jumps, high last line and unit / individual flexibility are only heightened.

Tactical Observations: Villarreal CF Under Quique Setién (Part 1)

When facing an opponent who wanted to play out from goal kicks and in their own third, Villarreal would proactively look to press the opposition high in order to limit their time and space on the ball. This press aimed to force a turnover, either high up the pitch or in their backline following a hurried forward pass.

Villarreal would execute their high press from an initial starting 4-4-2 or 4-1-4-1 high block shape which featured a very aggressive and high last line, predominantly positioned on or near the halfway line to help compact the space in the opponent’s half. Whether in their 4-4-2 or 4-1-4-1 starting shape, the Villarreal high press would involve a number of positional jumps to support their first and second lines of engagement. To help showcase some of these descriptions in practice, see the visuals below. Starting with Figure 3a where Girona are playing out from a goal kick against a 4-1-4-1 high block.

Figure 3a

In this scenario, Gerard Moreno curved his press to the Girona goalkeeper and put the left-sided central defender in his cover shadow, thus cutting the pitch in half. Behind him, each of the Villarreal second line oriented themselves based on their assigned opponent(s). Whilst Baena, Capoue and Chukwueze (out of shot) have a single Girona player to cover, Pino is in between two. The young Spanish forward will only push out to the player on the wing when a pass is made to him, as he also needs to ensure he covers the inside passing lane (see Girona player behind him).

However, Pino cannot be in two places at once, so in the event that he needs to jump up, the Girona player behind him will need to be covered regardless. And as Figure 3b below demonstrates, in this instance, the covering player was Pau Torres jumping up from the last line. But, despite Torres anticipating and making this jump, it was not required, as the Girona goalkeeper opted to go long to their forward line which only resulted in Villarreal regaining possession (note the height of the last line too).

Figure 3b

What cannot be seen in the visual above is a second Girona player in the bottom right corner of the image. This is the Girona wide right midfielder who is hugging the touchline and whose very presence pins the Villarreal left fullback (Johan Mojica in this game) from jumping up to engage the free Girona player between-the-lines, thus meaning it’s tasked to Torres.

This type of out-of-possession decision-making of ‘who picks up who’ and ‘who jumps and who stays’ was an ongoing narrative watching Villarreal across these observed matches. Whilst the majority of the side were typically player-orientated in their high press; a few players, like Pino, Torres and Mojica in the example above, were often ‘in between’ multiple opponents. And even though Setién had clearly drilled his team with set plans, and alternate plans for the different scenarios which may arise, the opposition’s movements would often test this organisation.

For readers familiar with TIFO’s Jon Mackenzie, this pressing approach from Villarreal may begin to sound like ‘hybrid pressing’ which is expertly explained in this article. In essence, ‘hybrid pressing’ is when a team seeks to get “the benefits of both zonal and player-oriented systems.” In this concept, the in-between players can be defined as ‘hybrid players’ who take up a “number of marking responsibilities in order to protect a team’s zonal structure even when breaking it in certain phases.”

As per Jon’s article, one way of helping categorising hybrid approaches is by “identifying where the pressing team is allowing the weakness in their structure to exist once they press out of their zonal system.” So a team’s hybrid press can be either vertically-weakened (allowing a weakness in the back line) or horizontally-weakened (allowing a weakness to open up in the wide areas of their own team).

In Villarreal’s case, they certainly fall in the vertically-weakened bucket. Whilst they ideally want to maintain a +1 coverage in their last line i.e. having an extra defender versus the opposition forward line – and the Yellows often initially start like this at goal kicks before the ball is live – they are more than prepared to risk going player-for-player in their last line by having defenders jump up to support the high press. As per against Girona.

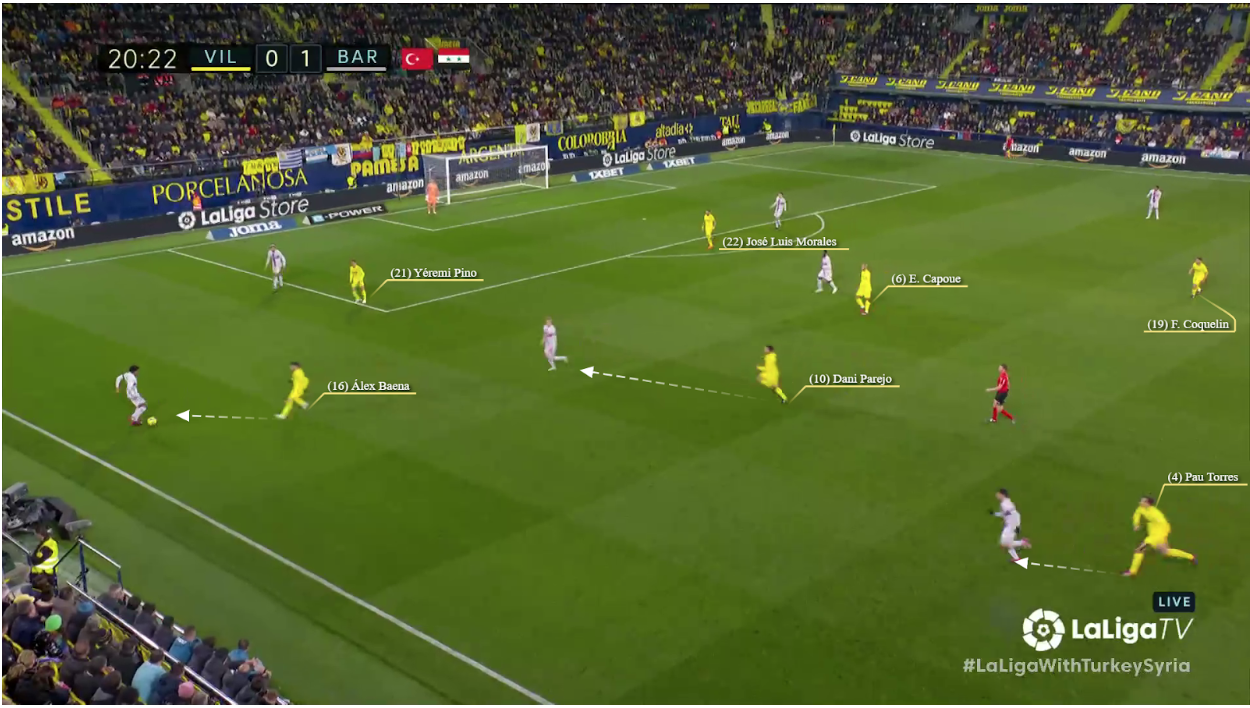

Here are some more examples of this approach in practice. In this instance against FC Barcelona (see Figure 4a below), Villarreal are pressing the Catalan side from their 4-4-2 high block using a hybrid press.

Figure 4a

In their first line, Pino is pressing the right-sided central defender and José Luis Morales is covering the goalkeeper and left-sided central defender. In their second line, Francis Coquelin (right-sided midfielder in this game) covers the left fullback, and Baena and Capoue are initially tasked with prioritising covering the Barcelona double pivot, but this can leave the right fullback free so Baena can also have the dual responsibility of getting out to him when in possession. This leaves Parejo, who in addition to initially covering any players between the lines, would jump up to cover the Barcelona double pivot (most typically the midfielder Baena passes on).

The action picks up below in Figure 4b, where you can now see how Villarreal’s hybrid press has adjusted with Baena pushed out to engage the right fullback, Parejo has jumped to pick up the unattended Barcelona double pivot player and Torres has jumped out of the last line to cover the player between-the-lines who Parejo was previously near.

Figure 4b

Following this chain reaction of jumps, the ball-sided Barcelona double pivot (Frenkie de Jong) received a pass from the right fullback. But, due to Parejo’s pressure, his only option was a pass backwards to his goalkeeper who quickly got put under pressure from Morales. As a result, Marc-André Ter Stegen opted to go long where you can see in Figure 4c below how Villarreal were left player-for-player in their (disjointed) last line and also that they regained possession following this direct pass.

Figure 4c

In another example, this time away from home against Real Madrid, in Figure 5a below you can see Villarreal in a high press following a number of positional jumps. This has involved their left fullback (Alfonso Pedraza) jumping up to the Real Madrid right fullback, as Pino (wide left midfielder in their mid-block) is tasked with pressing the right-sided central defender when high, and, this time, Torres has moved out to the wing to pick up the right-sided Real forward.

Figure 5a

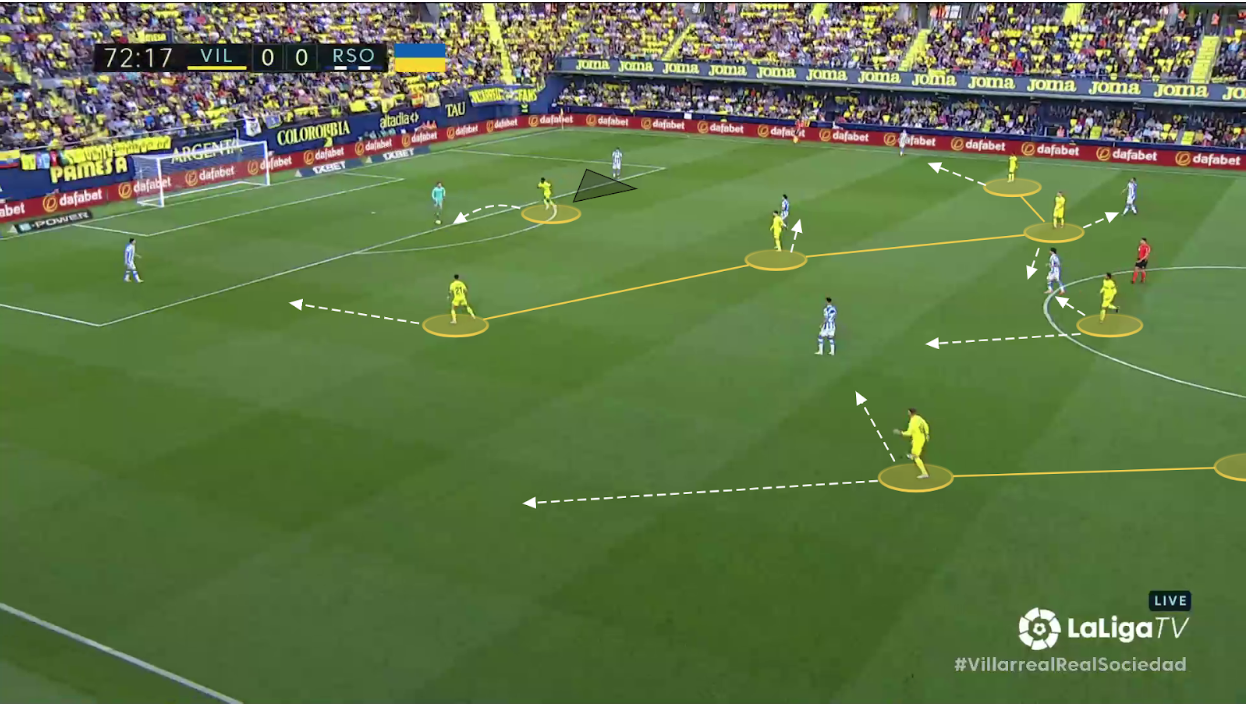

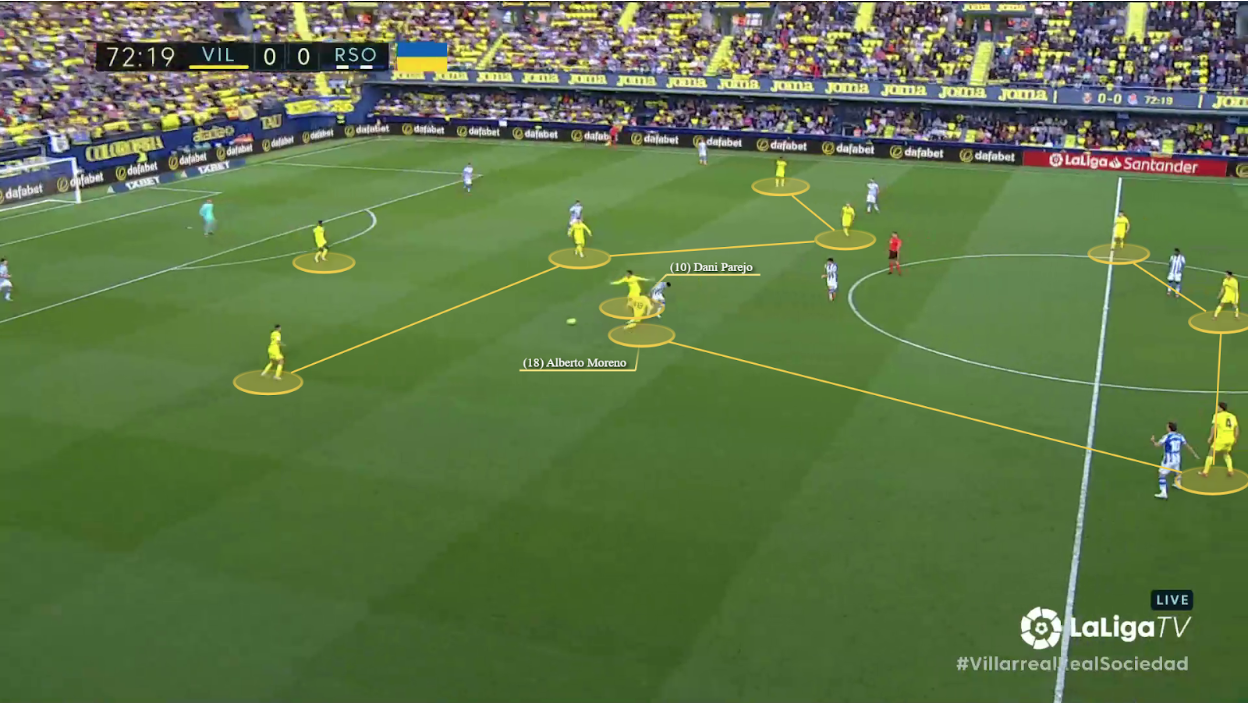

In the final of high (hybrid) press examples, see Figure 6a below against Real Sociedad. Here, the 4-1-4-1 high block had begun to initiate its pressing responsibilities. But due to Sociedad’s midfield diamond, Villarreal have had to adapt.

Figure 6a

In the first line of the press, it’s pretty standard; Jackson has curved his press towards the goalkeeper, cutting off the left-sided central defender in the process. In the supporting line, Pino is primed to press the right-sided central defender and Chukwueze is locked on the left fullback, again similar roles to they’ve had before. But in central areas, it gets a bit more interesting.

Baena (left-sided midfield 8) is tasked with getting close to the midfielder at the base of the Sociedad diamond, then Giovani Lo Celso (right-sided midfield 8) is tasked with covering the left side of the diamond. Parejo is initially covering the tip of the diamond (who also happens to be David Silva, perhaps explaining why a number of arrows are pointing at him). And this leaves the Sociedad right-side of the diamond, who is currently in space but has both Parejo able to step up to him if needed and also Alberto Moreno (Villarreal left fullback) who has the dual responsibility of covering both infield and the Sociedad right fullback.

This passage of play concludes in Figure 6b below where Parejo and Moreno swarm onto the Sociedad midfielder on the right side of the diamond, forcing a turnover. Also note in the image below the remainder of the Villarreal last line, which because of Moreno having this hybrid role, have been able to keep a +1 coverage against the two opposition forwards.

Figure 6b

To wrap up Villarreal’s high block and high press section, here’s some quantitative data to balance all of the above qualitative observations. According to Understat, post-World Cup – a more accurate period to review Villarreal under Setién – the Yellows ranked third lowest for Passes Per Defensive Action (PPDA) across all LaLiga sides (7.99). For anyone unaware – very unlikely for readers of Breaking The Lines – PPDA is a proxy of pressing intensity at the team level, used to try and capture the degree to which an opponent is pressuring the opposition when they don’t have the ball (definition stolen from The Athletic).

A low PPDA number indicates higher intensity when trying to win the ball back. It is worth clarifying that both these ‘qualitative’ and ‘quantitative’ means are only indicators of Villarreal’s out-of-possession approach stylistically, as opposed to quality. So we’ve seen what Villarreal do when defending high and in the middle third, now let’s move onto their low block and how they try to limit the opposition from creating chances, having shots and ultimately scoring goals.

Once the opposition get the ball into Villarreal’s own third (sometimes, due to the way they defend further up the pitch this doesn’t take too long), the Yellows aim to quickly retreat into some variation of a 4-5-1 / 4-1-4-1 block. See visuals 7a, 7b and 7c below for examples in practice.

Figure 7a

Figure 7b

Figure 7c

But at times, any distinct defensive and midfield lines are difficult to distinguish, and the label is not really important. What can be identified though, as visible in the screenshots, is that the team’s units can collapse into each other, with the priority being to defend in numbers, be compact and protect the box.

When required, the wide midfielders can drop on the outside of the back four and Parejo can drop in between the two central defenders too. One specific trigger for Villarreal to pack their box is a pass out wide to an opponent who has space to cross on the wing. Even in their low block, Villarreal will aim to push up and engage the opponent when in possession centrally, gaining yards as they do so. And if the opportunity arises, the Yellows will not hesitate to attempt an offside trap even on the edge of their area. There’s that Setién acceptance of risk for the reward value again.

To quickly touch upon when Villarreal won back possession from their low block setup, they did look to instigate counterattacking situations, using the likes of Chukwueze, Jackson, Pino and Baena. But in the observed set of matches, these attacking transitions felt like an underutilised weapon in their armoury, especially considering the profile of players at their disposal. It was only towards the end of the season when Jackson had a continued run of starts (so a striker to keep up with, and combine, with Chukwueze and Pino ) that Villarreal began to benefit from this.

So that’s all of the defensive phases covered. Before moving onto Villarreal’s inferred strengths and weaknesses out of possession, let’s look at some statistics. According to Understat, post-World Cup – again, a fairer period to judge Setién’s impact on the team, and when all of these eleven observed matches occurred – Villarreal conceded 30 goals, the joint 9th highest in the league. From an expected goals against (xGA) perspective, it was 34.18 xGA, the 10th highest in the league.

These metrics read as pretty much league average. But for a team who were challenging for a top-four finish, that is perhaps not a positive. Across these 24 matches, following the LaLiga restart, the Yellow Submarine kept five clean sheets. (Whether an indicator, coincidence or irony, they won all five of these games).

How Villarreal Became European Football’s Ever-Present Underdog

In the same 24-game period, Villarreal had an ‘above average’ goal-scoring return with 44 – the second-highest number of goals scored in LaLiga. So scoring goals was not Villarreal’s problem, but failing to keep them out cost them points. But should this all be attributed to their out-of-possession approach?

Strengths and Weaknesses

It’s clear that Villarreal have specific plans out of possession. As described and shown throughout this piece, Villarreal are not afraid of pushing players forward in an attempt to disrupt the opposition and regain possession. They have flexible ways of achieving this and it’s been shown to work (a 3-2 victory at the Bernabéu against Real Madrid is testament to this and whilst this win cannot be solely accredited to the out-of-possession approach, it certainly helped). Plus, the team accumulated 43 points, the joint-fourth-highest in the league following the World Cup, helping the club finish in fifth position.

But whilst Villarreal’s dynamic front foot approach is admirable and is certainly a strength at times, on the flip side, it can also be a hindrance in the respect of its exploitable. The sight of multiple Villarreal players frantically running back towards their own goal after being bypassed, or following a direct piece of play, was a frequent occurrence, not just across this set of observed matches, but also various times during individual games.

In addition to this, sometimes the complexities of players’ responsibilities out of possession could leave them visibly confused as to where to position themselves and who to track, especially against interchangeable opponents. This was evident on numerous occasions on their left-hand side with their left fullback often left with no coverage ahead of him, especially when Pino (typically left-sided midfielder for Villarreal out of possession) had pushed up to press the opposition’s first line in build-up and therefore had large distances to recover in order to get back into shape in defensive transitions.

For clarity, however, the above points are not to suggest that Villarreal’s out-of-possession tendencies were the main causation for the goals conceded in the eleven games observed. No, in fact, a number of ‘goals against’ in these games came from individual errors in Villarreal’s build-up play.

And this is an appropriate way to conclude, as in Setién’s quest for ‘control of the ball’ – or as he puts it: “we always try to be at the forefront with the ball” – the Villarreal coach is prepared to accept the consequences (risks) of their out of possession approach (like he does in possession), as he values the rewards that it brings more highly.

Closing Thoughts

Across this two-part series, we have delved into some of Villarreal’s most common in and out-of-possession tendencies under Quique Setién. It is fair to say that the theme of risk versus reward was prevalent in all aspects and phases of their play. And how these approaches would have fared for Villareal across a whole season, who knows.

Heading into the 2023/24 season, Villarreal need to replace the individual quality, outputs and minutes of both Pau Torres and Nicolas Jackson, and potentially Samuel Chukwueze, if rumours are to be believed. How the Yellow Submarine adapt without such key players from the previous season will be a fascinating watch. But one thing is for certain, for however long Setién is at the helm, you will know that both in and out of possession, the focus will be centred around controlling the ball.

By: @Tactics_Tweets

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Getty Images

All match screenshots were from Wyscout.