Tactical Profiles – a Stampede in Gladbach

Welcome to a new special series on Breaking the Lines! This tactical insight, attempting to profile the most interesting and creative tactical thinkers in football is a new initiative that will feature on the site every couple of weeks. First up: Marco Rose.

Having innovated his own aggressive style of Germany’s new-age style, Marco Rose – alongside prominent assistant Rene Maric – has finally returned to Germany, bringing with him the enthralling, attacking stampede of Red Ball Salzburg, with a few important alterations.

With his lightning fast counters and pack-hunting pressing, here’s how Marco Rose’s side have lit up the Bundesliga.

The Man at the Helm

Marco Rose came to the attention of the wider football world when his Red Bull Salzburg side – popular with hipsters and analysts alike – took to the Europa League and found a hunting ground. Their scalps included Lazio, Borussia Dortmund and Real Sociedad on their way to the Europa League semi-final, where they lost to Marseille thanks to a heartbreaking 117th minute winner.

Photo: Adam Pretty/Bongarts

Rose – who learnt his trade from Jürgen Klopp at Mainz – had already shown he was a predator in European competitions, having guided his Salzburg U19 side to the 2016/17 UEFA Youth League (where he engineered victories over the youth teams of Manchester City, Barcelona, PSG, and Atletico Madrid), and his reputation has only grown more impressive since.

He preaches attacking football, but not in the gung-ho, all gun’s ablaze fashion. His Salzburg side were devastating on the counter and were drilled to press at the right moments, lulling opposition into a false sense of security before striking at them with overwhelming speed.

At Gladbach, he has largely tried to impose similar philosophies, albeit with a few noticeable upgrades.

The Formation

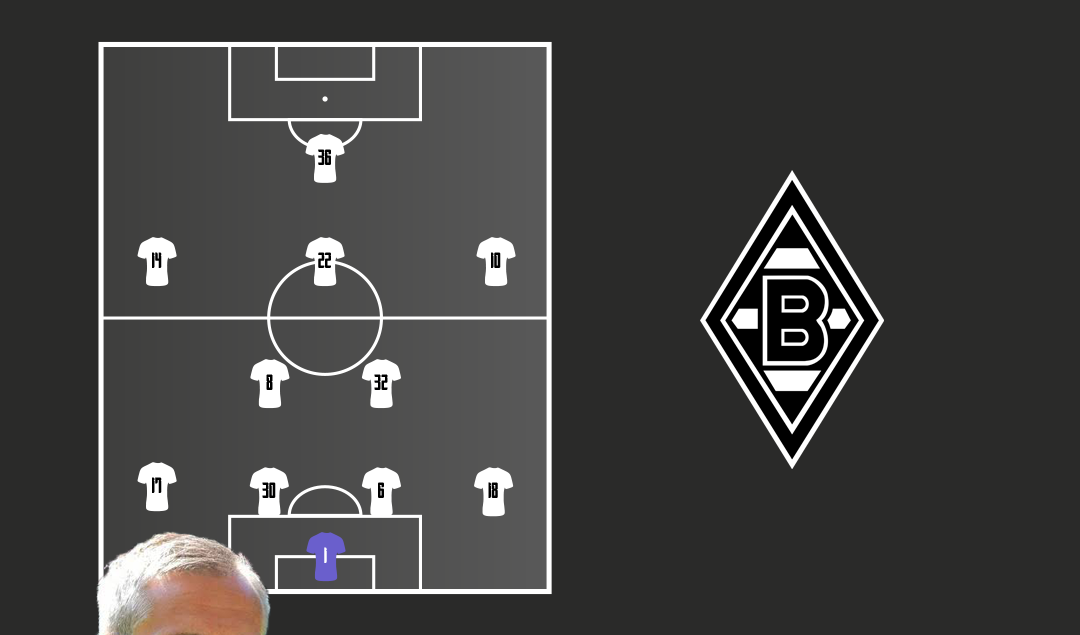

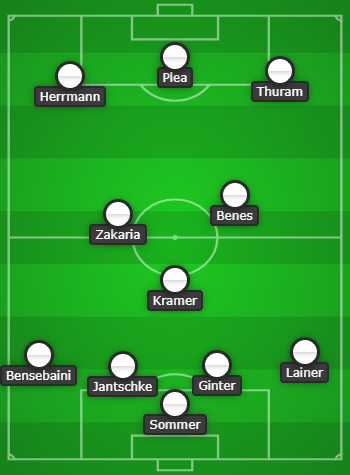

At Salzburg, Rose mostly employed a 4-3-1-2 in a diamond shape, though Rene Maric spoke of its versatility; able to become a flat 4-4-2, a 4-3-3, a stretched-out diamond or a 4-3-2-1 depending on where the pieces are placed. This season, Rose has tinkered, going from his favoured formation to a more regimented 4-3-3, as seen below.

The Counters

Of all the things avid watchers of Germany’s topflight would associate with Borussia Monchengladbach under their previous manager Dieter Hecking, speed is certainly not one of them.

The technical prowess of Captain Lars Stindl and Raffael, the slow, side-to-side probing of a midfield designed to keep the ball and find chinks in the opposition’s armour was in itself a brand of attacking football that flourished in the early part of last season, but floundered as Dieter Hecking’s plans fell apart alongside Gladbach’s Champions League ambition.

“I feel like we need to do things differently” Sporting Director Max Eberl said upon sacking the grizzled veteran. Indeed, the fresh young face of Marco Rose has instilled something very different in this Monchengladbach side.

Devastation in transition.

Things always happen in threes: Gladbach hunt in packs of three to win the ball (more on that later) then bring the ball through midfield in groups of three (or more, depending on the situation.) Whether through the centre, with options on either side, or down a flank with at least two outlets for the final ball, Gladbach’s counter attacks are, above all, disarmingly quick.

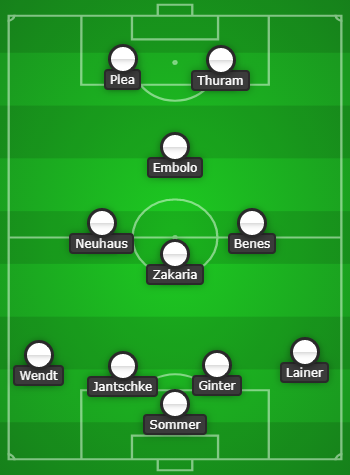

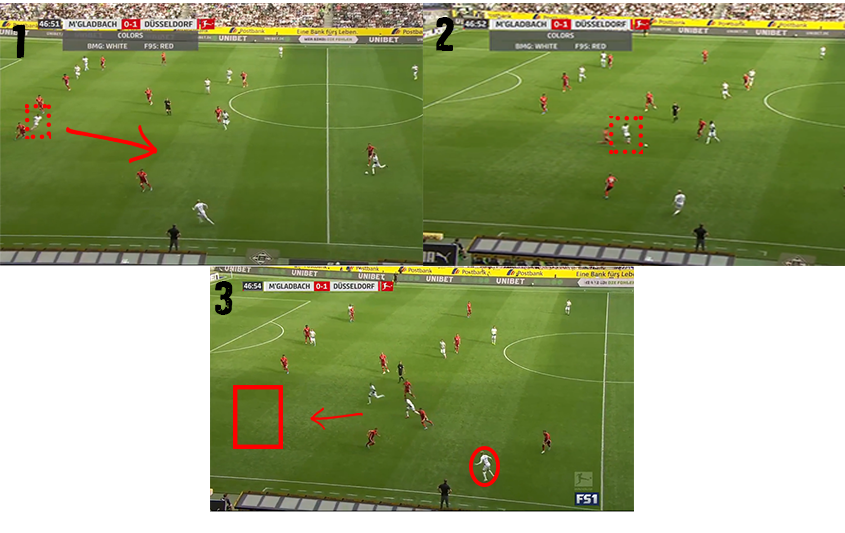

An example of a congested press and fast counter: the first image shows the congested diamond shape in midfield, the second shows a pack-like press in midfield and the third shows how fast the ball comes out to the attack, where a counter is sprung.

It’s been a key facet of this team to see one of the nominal strikers – for there are multiple – streaming down one flank, aided by someone coming down on his outside (usually a fullback) and another coming down inside, also behind him.

Rose uses strikers like half-and-half forwards, both central and wide, knowing there’s always a third attacking player there in case both end up on a flank. In his diamond, he often used Breel Embolo; who played as a striker and right winger at Schalke, in behind his strike pairing, not the kind of number ten who threads passes, but the kind who can dribble at defences and make runs.

The Swiss manager found two perfect players in implement such an idea in the form of last season’s top-scorer Alassane Pléa and this season’s shining light Marcus Thuram. When Gladbach attack, interplay between the two is encouraged and often necessary, given they try to drag defenders into space, but it’s their ability to unsettle an opposing defence with supremely fast dribbling and movement which is most critical.

Against Augsburg, Thuram – who began the game on the left of a 4-3-3 – dragged deep and picked up the ball near the halfway line, then took it all the way into the box and pulled it back for Denis Zakaria – another key cog in Rose’s machine – to open the scoring inside two minutes.

The Pullbacks

Which leads to another facet of Rose’s attacking play; pullbacks. Get wide, then pull the ball back to an oncoming attacker. The areas from which those shots usually come is what’s known as the “half space” – or the area just outside and just wide of the box, around the point where its perpendicular lines intersect.

Both Zakaria’s run for the first goal and Herrmann’s run for the second come through that area, where one of the forwards has already gotten wide and driven in behind the defence.

Both goals vs. Augsburg come from pullbacks to players coming from the half spaces

At Salzburg he used these sorts of spaces – the ones around each corner of the box – to create uncertainty in an opponent’s defence; the idea being that when a creative player got into that area, it would be unnerving and unpredictable. At Gladbach, Rose has taken that and inverted it. Rather than having his players get on the ball in those areas, he wants his players to make runs into it.

In essence, Rose’s system of attacking creates the fear of being surrounded by the counterattack.

Diagonality and Space

To achieve such blistering counterattacks, however, the ball has to move through the midfield at speed. Rose has switched to a 4-3-3 in his last three games, to get the most out of the front three.

However, the two wider forwards always come short, hoping to drag a defender out of position and create a hole, which can either be filled by a fellow forward – essentially meaning the front three are constantly shifting – or the attacking midfielder. The latter role has been filled to perfection by Lászlo Bénes, who acts as the most attacking of the midfield three.

Alassane Pléa comes short to receive the ball, then lays it off to the fullback Oscar Wendt quickly, creating the space as a defender is dragged out.

For the ball to get to the front three, however, it has to go through the middle, often at speed. To achieve this, Rose implements two things. One, a diamond shape. Two, diagonal passes, often played short, to dart through midfields like a game of pinball.

After winning the ball back, rather than hoofing it long, a system of one-touch passing punctures opposition midfields, getting the ball to the front three with a smooth urgency. The pack mentality, of always having someone to play the ball to quickly, works best when there is a pack of three or four, organised in a diamond.

Furthermore, it only succeeds when that pass goes forwards, else the opposition have time to set themselves. Passing it directly forwards relies on movement that might not always be there, whereas having someone diagonally ahead of you means they can take the ball and play it quickly themselves, rather than having to waste precious seconds turning and looking at who’s next.

By the time the ball comes out, it is often with one of the front three, who (as mentioned) come short with their back to goal and play an equally quick pass to an oncoming midfielder. It is, in essence, a way to go from back to front with rapidity, without the ball needing to leave the floor.

Hunting in Packs

Rose’s defensive pressing game stems from one of his mentors; Jürgen Klopp, as does a lot of forward-thinking football in Germany. Rose’s, however, is less about the timing of the press and more about the areas. His midfield congests the centre, effectively tempting their opposite numbers to stretch the play through the wide areas.

Once the opposition has it out wide, they wait for the opportune moment; usually when an opposition player has little support and can only cross or try to dribble his way out. That is, of course, if the opposition bypass their initial press; where the forwards and most advanced midfielder swing like a pendulum, forcing the opposition out wide (in their own half) and hunt them down.

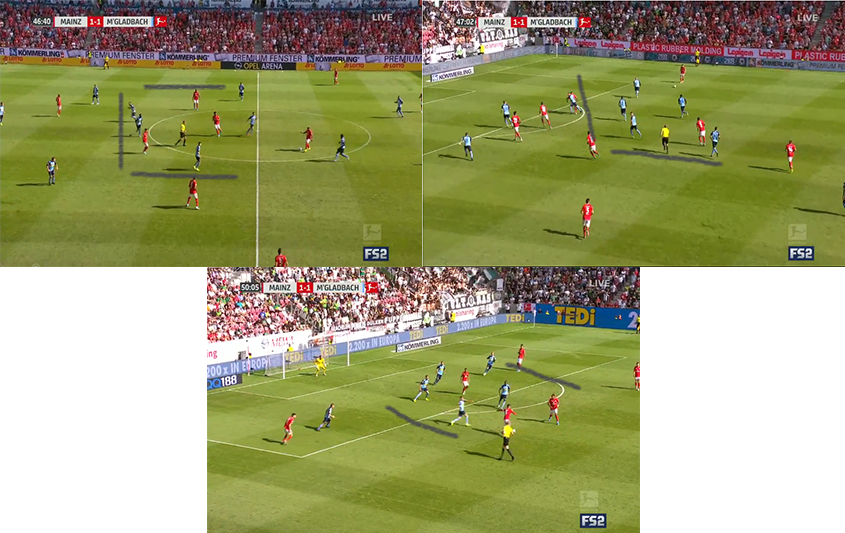

THREE different examples in the same phase of Gladbach sectioning off the centre of the pitch, prompting Mainz to go out wide. The weakness comes in the second image, where a cross nearly finds Robin Quaison.

The proof has been rather blatant: under Dieter Hecking, Gladbach contested the least duels in the league. Under Rose, they contest the most.

Winning the ball back out wide means the opposition aren’t ready for it to come back through the middle, where Gladbach will almost always have numerical superiority, and the counter begins again.

The weakness of this approach comes when, like against Leipzig, a fast attack can breach their defence with good dribbling, receiving the ball behind the advanced fullbacks, or a ball comes over the top of their centre halves and a lightning forward like Timo Werner can punish their proactive press.

Conclusion

Marco Rose’s notoriety came from his “new age” techniques; Rene Maric is a former tactics blogger, Salzburg’s use of analytics and advanced scouting is now famous and the versatility of his diamond system, as explored earlier in the piece, means he is not just a gung-ho attacking manager, but an intelligent one too.

The proof is in the pudding, at the time of writing Gladbach are top of the Bundesliga. Whether they stay there is very much up to the mettle of those around them, but it is a promising sign for a manager who, after his proving ground in Austria, has returned to Germany with a brand all of his own.

By: Alex Barilaro

Photo: @GabFoligno