Why Manchester United Struggle to Break Teams Down Under Ole Gunnar Solskjær

Since taking charge of Manchester United in December 2018, Ole Gunnar Solskjær has proven time and time again his ability to grind out a victory against top opposition. He demonstrated his tactical nous in his fifth Premier League match, which saw United muster a 1-0 victory against Tottenham Hotspur. A month later, Solskjær sealed a three-year contract after his side overturned a 2-goal deficit at the Parc des Princes to eliminate Paris Saint-Germain from the Champions League.

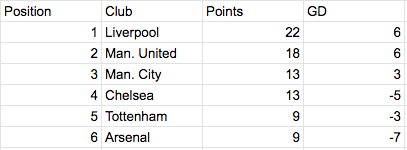

Throughout his time at Old Trafford, Solskjær has proven his worth when going up against the traditional top six sides in the Premier League. In the top six ‘mini-league’ from the 2019/20 campaign, United finish second to Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool with an impressive 18 points from 10 matches.

However, it is against the minnows in England, bottom-half teams that sit back and hit on the counter, where United truly struggles. Teams such as Sean Dyche’s Burnley and Roy Hodgson’s Crystal Palace have taken points off United by remaining compact and forcing them to attempt to break them down in possession, before taking advantage of their lack of pace in central defense.

Whilst United finished on 66 points last season, with a red-hot streak during Project Restart that carried them to third place in the league, they only took 48 points from 28 matches against teams that were outside the top six.

In the above graph, we can see how the top six teams have fared against Wolves, Southampton, Crystal Palace, Burnley, Newcastle and West Ham since the start of the 2019/20 campaign. Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City sit second-bottom with 27 points from 14 matches, whilst United find themselves dead-last with an astonishing 17 points from 14 matches.

That’s 17 out of a potential 42 points, or 25 points dropped. To put that in perspective, Liverpool only dropped 15 points during the entirety of last season, and eight of those points were dropped after Liverpool sealed their first ever Premier League title on June 25.

Manchester United’s Tactical Approach

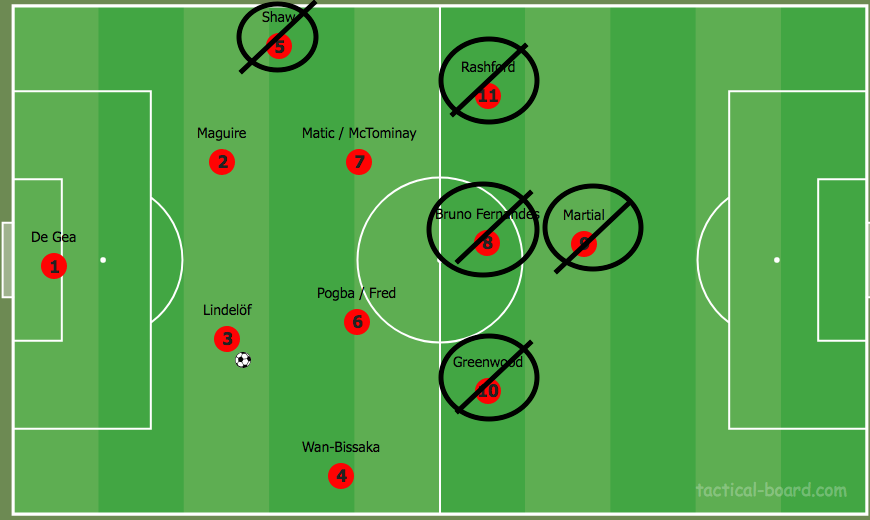

Whilst United have briefly experiment with a diamond 4-4-2 and a 3-4-1-2 this season, they have predominantly lined up in a 4-2-3-1 this season. It should be noted that although Mason Greenwood cemented a starting spot on the right wing during Project Restart, he has often found himself out of the team this season with Solskjær preferring Juan Mata in recent weeks.

United have the individual quality in attack to pick apart defenses and wreak havoc on the opposition via their combination play, as seen in the below example against Sheffield United. Paul Pogba plays a pass to Bruno Fernandes, who calmly flicks it into the path of Anthony Martial.

The Frenchman is tightly marked by Chris Basham, so he plays a quick one-two to Marcus Rashford, whose return pass evades George Baldock and Basham. Martial latches onto the pass and calmly dinks it over future teammate Dean Henderson, completing the first Premier League hat-trick of his career and sealing a 3-0 victory for the Red Devils.

However, United typically face mid-table and bottom-half sides that remain more compact and organized than Sheffield United — who were amongst the worst teams in Europe during the first weeks of Project Restart. It is against these teams that sit back in low blocks where United’s lack of structure in their build-up play comes to haunt them.

Manchester United in Possession

One of the biggest reasons why United struggle against deep blocks is that they don’t play enough long passes. Conversely, they also don’t circulate possession quickly enough and stretch apart the opposition to the point where playing a long pass can set up a dangerous goalscoring opportunity.

According to fbref.com, Manchester United are 19th in the league for long balls attempted this season, just as they were in the previous campaign. United have attempted 606 long passes in their first seven Premier League games; on the other hand, Liverpool and Chelsea have attempted 972 and 905 long passes, respectively, in their first six encounters in league play this season.

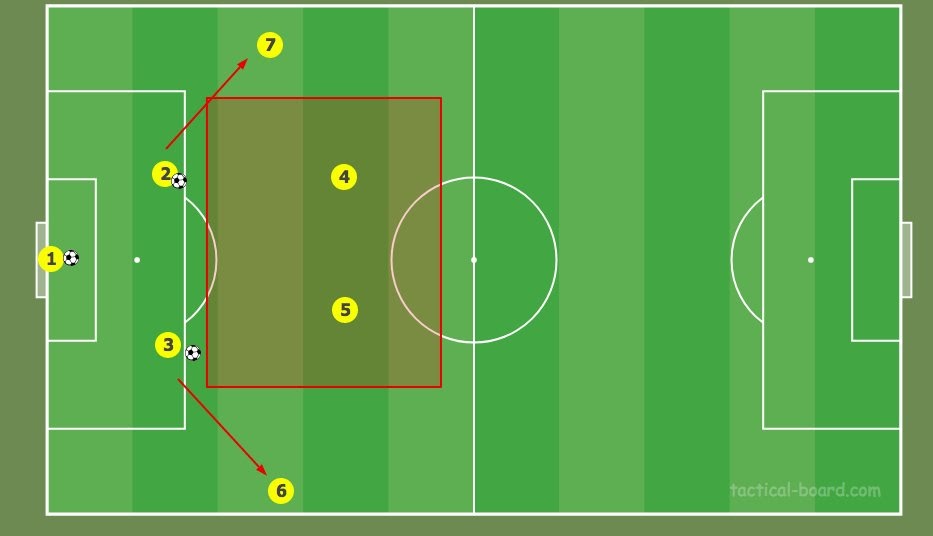

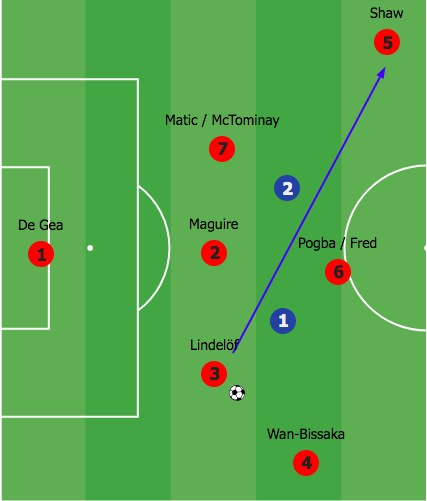

If Victor Lindelöf has the ball and will only play short passes, his options in possession become limited. As shown in the above image, there are only four options that Lindelöf is likely to pass to. If the opposition succeed in blocking off central areas, Lindelöf only has two passing options: Harry Maguire or Aaron Wan-Bissaka.

Due in part to Lindelöf’s conservative nature on the ball, United fail to stretch apart the opponent, who are able to accurately predict where the ball will go. However, if United were to regularly play long cross-field passes, they would be able to quickly switch the point of attacks and get their wingers 1v1 with the opposition full-back, a kind of move that players such as Marcus Rashford thrive upon.

It’s also possible that the opposition would compensate for United’s width by making their block wider, thereby increasing the amount of space in central areas and allowing more space for United’s forwards to exploit. Whilst the attempted long balls may not always meet the intended target, they can force the opposing defenders to move out of their shape in order to cut out the pass.

This pulls opposing players out of their usual positions, and if United win a second ball or cut out an opposition clearance, they can enjoy a dangerous goalscoring opportunity. In short, playing direct, long balls helps to stretch the opposition’s defence apart and create space in central areas.

Lack of Movement

Another reason why United struggles to break down compact sides in possession is the lack of off-the-ball movement from forwards. Whilst their attackers offer movement when the ball is near the goal, it is during the first second phases of play where United’s lack of movement from their forwards wreak havoc on their ball progression.

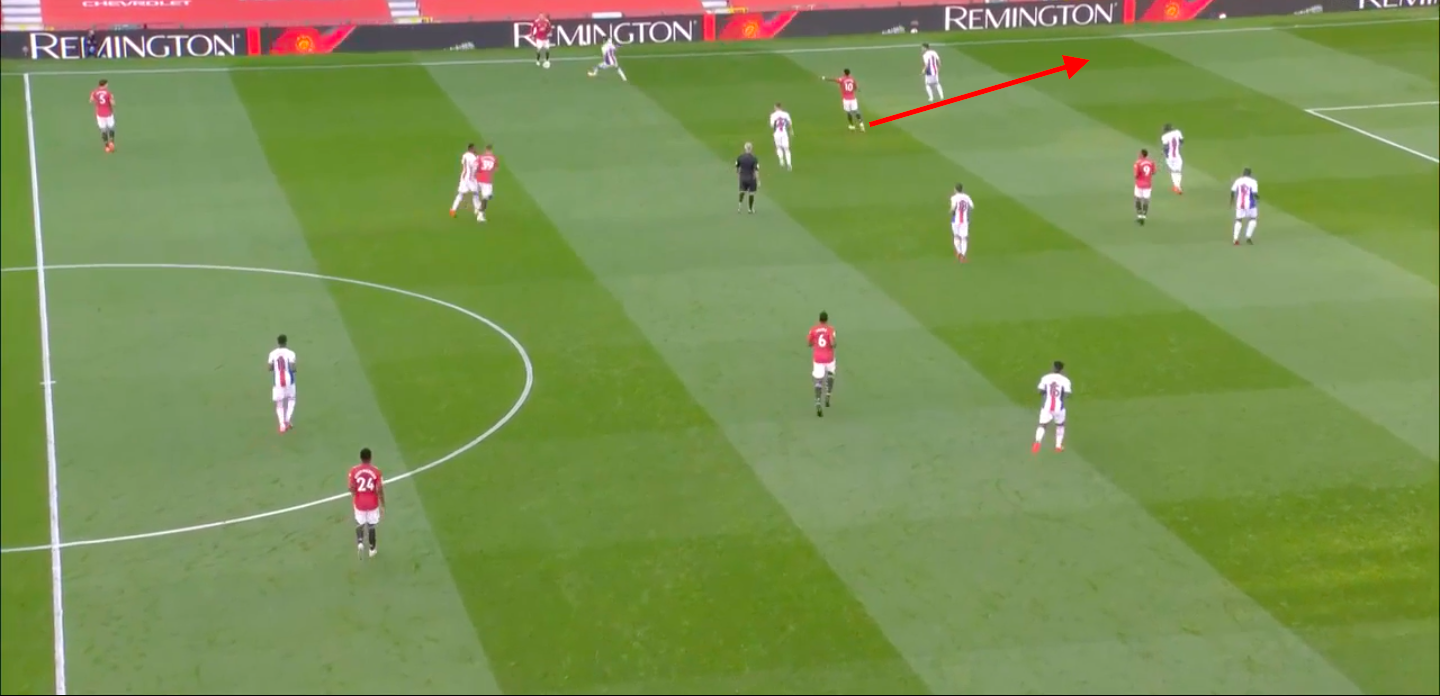

In the above example against Crystal Palace, United’s defenders are forced to horizontally shuffle the ball in order to evade the pressing strikers. There are no runs in behind from United’s forwards, nobody dropping deep to receive a pass, and as a result, they fail to stretch apart the opponent’s deep block.

Let’s compare that with this example from Liverpool. Roberto Firmino drops deep from his center forward position to provide a short passing option, although Virgil van Dijk instead decides to play a chipped pass to Andrew Robertson, who is making a run in behind the defense.

United’s forwards lack the movement required to break down a deep block, and as a result, the opposing players are less likely to be dragged out of position and they will have an easier time predicting where the ball will go. Whether it’s runs in behind the defense, finding space in between the lines, or drifting into wide areas, clever movement forces the defending team to react and in turn opens up space that can be exploited.

Whilst United’s defenders certainly need to take more risks on the ball and play deeper passes in order to open up compact sides, United’s forwards must exhibit greater off-the-ball movement in order to keep opponents guessing and stretch apart the low block.

Vulnerability to a Press

Solskjær’s 4-2-3-1 is often bypassed whenever teams press their double pivot, and due to Nemanja Matić’s lack of speed and Pogba’s inconsistent work rate, these dispossessions in the middle third can prove to be death sentences for United.

In this example against Tottenham Hotspur, Pogba receives a pass from Wan-Bissaka and is immediately closed down by Pierre-Emile Højbjerg. He spins past the Danish midfielder, but he loses track of the ball and is dispossessed by Érik Lamela. Whilst these central midfielders are sometimes at fault for dwelling on the ball, United’s build-up structure should be tweaked in order to avoid these risky situations

Pogba lost the ball for a number of reasons: he took a heavy touch, he either didn’t see Lamela coming or he didn’t gauge the distance between himself and Lamela, and he didn’t receive the ball with his body closed off from the opponent, and as a result, he couldn’t use his body to shield the ball. However, Wan-Bissaka made the initial mistake by playing a pass to Pogba in the red zone, despite the fact that he was heavily marked.

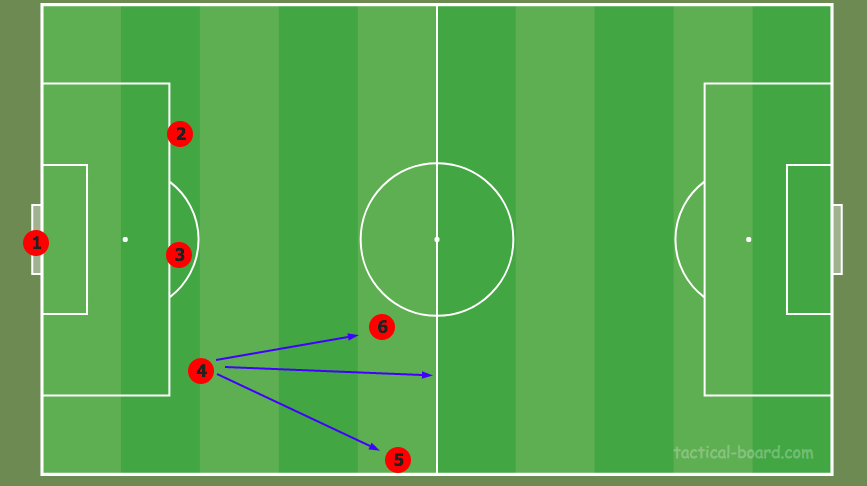

The red central area of the pitch is the ‘danger zone’. When operating in a 4-2-3-1, in which two central midfielders are typically positioned inside the danger zone, the opposition can close down the team from more angles and reduce their time on the ball, thus making it even harder to safely progress the ball in the second phase.

On the other hand, when the team’s forwards receive the ball on the flanks, they can be pressured from fewer angles. These attacking players can also receive the ball with an open body position, allowing them to receive in ample space with plenty of room to scan his surroundings and turn into advanced areas.

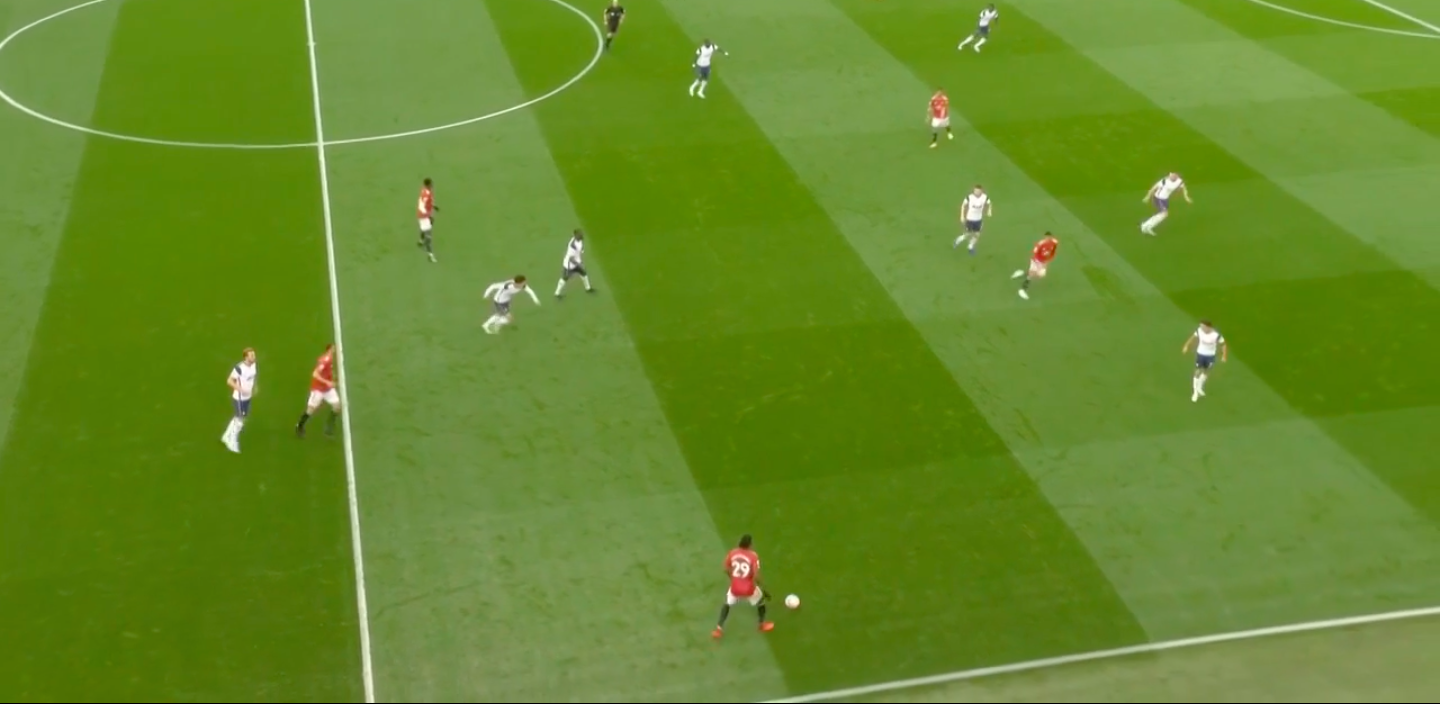

However, United often struggle to progress the ball forward when the ball moves wide in build-up, as seen in this example against Tottenham Hotspur. Wan-Bissaka has ample time and space on the ball, but he doesn’t have any simple passing options. Matić is tightly marked by Kane, Fernandes and Greenwood are surrounded by a sea of Tottenham players, and Pogba is unavailable for a pass.

With no real passing option, Wan-Bissaka is forced to play a back pass to the right-sided center back: Eric Bailly. This is a common occurrence for United’s players and it explains why they often force risky passes into their double pivot; it’s often their biggest method of progressing play into the final third.

In this example against Crystal Palace, Luke Shaw finds himself tightly marked by Andros Townsend on the left flank, and his best option is to pass backwards to Maguire. To help progress the ball from the wide areas, Solskjær could instruct his wingers to make more runs in behind, which could allow the fullbacks to play more long balls down the channels which the wingers could then chase down.

If the winger gets to the ball first, they can get 1v1 with the full-back deep in the opposing half. Moreover, long balls down the channel can drag opposition players out of their shape which can then create space in other areas. United can also create counter-pressing situations as even if the opponent get to the ball, there are second or third balls to fight for. If they win these duels, they can get the ball in the opposition’s half with the opposition’s structure disorganised and stretched apart.

This type of move offers United another method of progression and gives them another way to test their opponent. In general, the wingers holding width and staying on the touchline could help United improve their width by providing the full-backs with an option to pass down the line, and it could also create space in central areas as the opposition would have to cover United’s width.

Possible Solution

United could fix these issues to a degree by building out of the first phase with a back three, with one of the holding midfielders dropping in between the center backs and making United retain a 3-1 build-up structure. Matić excelled in this facet during Project Restart, allowing them to have a greater balance in defense.

The potential 3-1 build-up structure would suit United as the back three could find passes in between the lines from more angles, allowing them to exchange positions and advance further forward. A single pivot would have more freedom to roam and find space in midfield, whereas two holding midfielders playing in the Red Zone can sometimes reduce each other’s passing angles.

Moreover, the back three would allow for smoother, quicker circulation, allowing them to keep the ball moving and stretching apart the opposition as they continuously shuffle in order to remain compact against the ball.

The back three would help United retain numerical superiority against an opposing strike pair, and their fullback could then join the build-up whenever the ball is on their side, whereas the fullback on the other side would be available to receive a cross-field switch.

Going up against Ralph Hasenhüttl’s Southampton, United use a 3-1 build-up structure to evade Saints’s aggressive pressing. United’s defenders circulate the ball from side to side before finding Pogba, the single pivot, in ample space. Pogba roams forward before finding Fernandes in the left half space, and the Portuguese midfielder quickly finds the onrushing Martial, who slaloms past Kyle Walker-Peters before firing home United’s second goal.

Conclusion

Perhaps nothing sums up Manchester United’s oxymoronic form under Ole Gunnar Solskjær better than the fact that despite beating last season’s Champions League finalist (Paris Saint-Germain) and semi-finalist (RB Leipzig), they were thoroughly outplayed and beaten by Champions League debutantes İstanbul Başakşehir. Whilst United are suited to remaining compact and breaking down opposing sides on the counter, they tend to struggle when teams operate in a low block and give them a taste of their own medicine.

It is up to Solskjær to find new ways to improve United’s ball circulation, their usage of width, their movement in advanced areas and their direct passing. With United currently 14th in the Premier League, the onus is on the Norwegian manager to tweak his structure in order to fix these issues. If he fails to do so, the club hierarchy may have no other choice but to turn to out-of-work Mauricio Pochettino in a bid to turn their season around.

By: Rahul Mall

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Shaun Botterill / AFP