Hertha BSC vs 1. FC Union Berlin: A Complex Overview of a Complex Derby

In many respects, Berlin is an anomaly. The heart of geopolitical discourse for the best part of the 20th Century, the memories of a different world are still fresh in the minds of many of the city’s residents. Whilst there is no doubt that the fall of the Wall liberated the German capital’s soul, the assumption that it levelled the playing field between East and West (both of Berlin and the nation itself) is naïve.

On 9th November 1989, Günter Schabowski made possibly the biggest press conference blunder of all time. Having only been given a dossier (outlining new rules regarding immigration and cross-border relations between East and West Germany) shortly before having to address the media, a minor misinterpretation acted as a catalyst for Germany’s most famous piece of anarchy.

Schabowski started the press conference without having read the document, and when asked, “When does this [the immigration passes] go into effect?,” he replied, “As I understand, it goes into effect immediately, without delay.”

West German media therefore reported that the East German border was open for everyone. The message spread thick and fast, and within minutes, thousands descended upon checkpoints and started trying to pass through or even scale the wall (which up until this moment would have resulted in immediate death). East Germany had two choices; 1) Mercilessly gun down innocent citizens for reacting to misguided bureaucracy – or 2) Let them pass.

Fortunately, they chose the latter. Alongside the Cuban Missile crisis, this one decision helped prevent a potential World War III.

More than 30 years later, there is no clear and obvious divide, yet the phenomenon known as die Mauer im Kopf (the wall of the mind) still persists. Initially, there were jokes surrounding it – such as West Germans claiming those from the East wouldn’t know what a banana looks like, or the East claiming their kebabs were superior – but, as is the case with many geo-social divisions, the line between joke and spite has become blurred.

The capitalist nature of West Germany and consequent trend of Easterners migrating west in search of employment was the reason the Soviets initially constructed the Wall, and when the Wall came down, this trend was exacerbated once again. West Germany took advantage of new markets, with the East German state having no choice but to sell off companies to the West German private sector due to the East’s weak currency.

To make matters worse, those same companies were promptly shut down, as all the West wanted was for their competition to be removed from the market. Freedom gained, but financial security lost – the working class of the East felt hard done by, and betrayed. In a Financial Times opinion poll from last year, only 38% of East Germans said that German Unification was a success.

Photo: Washington Post

‘But how does this pertain to football?’, you ask. Well, this division shafted East Germany’s proud football heritage too. Powerful West German club chairmen cherry-picked the best players from East German clubs, luring them in with the promise of higher salaries.

Andreas Thom moved from Dynamo Dresden to Bayer Leverkusen just one month after the fall of the Wall; Matthias Sammer – a former Ballon D’Or winner – was also poached from Dynamo Dresden that year, this time by VfB Stuttgart. These are two high-profile examples, but there were plenty more. It decimated the quality of the East clubs, regardless of the fact they could now bring in foreign talent themselves, as they couldn’t compete in the free market whatsoever.

The issues were deeper than the mere economics of player recruitment too; potential sponsors of East companies which managed to survive by being bought out by the West still had very little financial clout, and West companies often weren’t interested in investing in East clubs. To make matters worse, the few West investments into East clubs ended up becoming train-wrecks of endeavors, with the most obvious example being Rolf-Jürgen Otto, who ruined Dynamo Dresden before later being imprisoned for embezzlement.

Photo: Frank Dehlis

Even the unification of the leagues was greatly imbalanced. In 1991, the West’s Bundesliga had 18 teams, while the East’s Oberliga had 14 teams. But rather than finding some means of equality by merging and/or then splitting them, the Bundesliga took reign, keeping all 18 of its teams with the mere addition of two Oberliga teams (Dynamo Dresden and Hansa Rostock).

A further six Oberliga teams were admitted to the 2. Bundesliga, and the other six sides went straight from being in the echelon of East German football to the 3rd Division of the new unified Germany. The dismemberment of the East’s structure, along with the strong-armed financial forays of the West clubs, led to many of the East’s clubs being set back a generation in terms of infrastructure.

Indeed, no East German side has ever won the Bundesliga, and Dynamo Dresden – arguably the most successful East German club at the fall of the Wall – were relegated in 1995 amidst financial ruin, and have never returned to the top flight.

The story of Union Berlin

Thus far, the picture I’ve painted regarding the East may seem to be all doom and gloom, but have no fear – enter Union Berlin. Founded in 1906 under the name FC Olympia 06 Oberschöneweide, they went through a succession of various rebrands, mergers and splits, before settling on the name that we now know them as in 1966.

During the years of the German Democratic Republic under the Soviet regime, Union were known as a symbol of the anti-establishment. A commonly held perception was that not all Union fans may be state rebels, but all state rebels were Union fans.

Every match, whenever a free kick was conceded near their own goal, fans would flagrantly start shouting Die Mauer muss weg (the wall must fall), a slightly humorous and ironic chant on the surface, but its innuendo entirely purposeful as it was the only time in which the anti-establishment fans could protest their dislike for the Wall without being punished.

It was during this period that Union and crosstown rivals Hertha struck up a friendly rapport, as Hertha fans from the West (able to freely visit East Berlin) would join Union on matchdays in order to show their support for the greater good of football. In return, Union fans would travel with Hertha to European matchdays outside the country in solidarity.

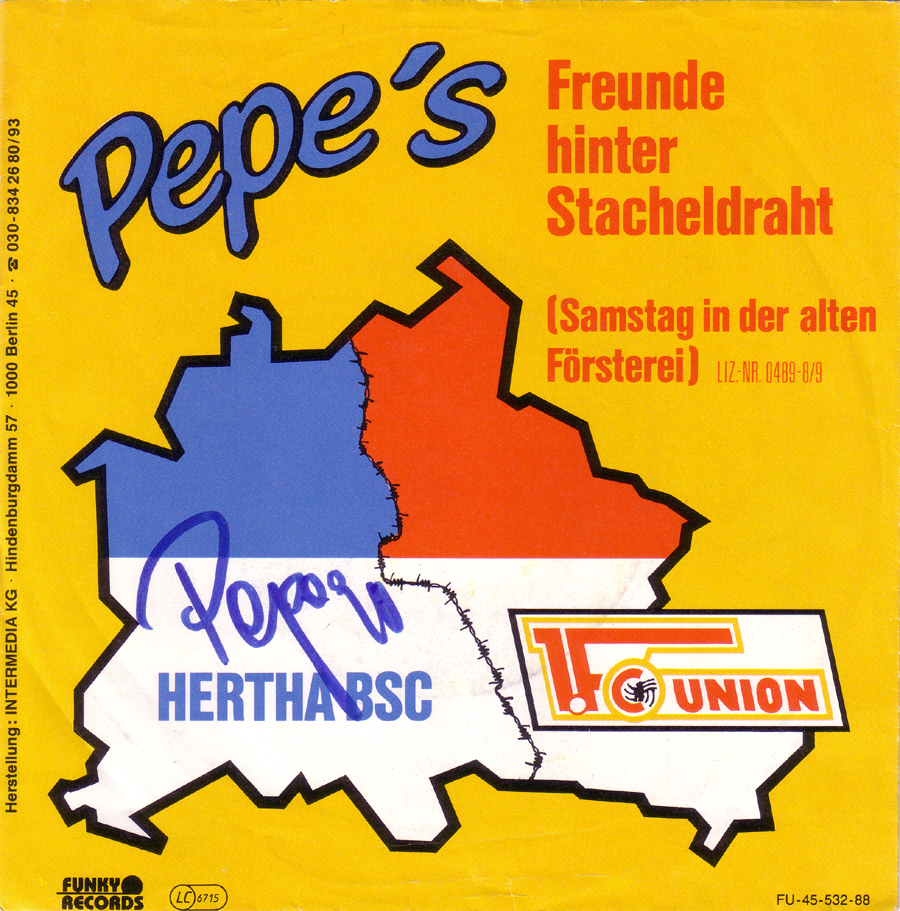

Such friendship led to them referring to the bond as Freunde hinter Stacheldraht (friends behind barbed wire). The punk, working-class aesthetic shared by Union fans was hated by the USSR, who saw such behaviour as a symbol of threat to the state. For Union fans, though, football and everything it represented on a cultural level was and still is more important than the result.

The fall of the Wall came at a time when Union were playing well but were threatened by imminent financial ruin. Upon the unification of the Bundesliga and its subdivisions, Union successfully applied for and received a license, and subsequently found themselves in the 3rd tier.

Whilst they successfully finished in the promotion spots during the first few years following reunification, they were barred promotion to the 2. Bundesliga due to not holding the required finances to gain a license for the league. It wasn’t until the 2000/01 season that Union managed to stabilise themselves financially in order to be promoted, having won the Regionalliga Nord.

This season goes down in Union folklore, as they also managed to progress to the final of the DFB-Pokal, where they lost 2-0 to Schalke but still qualified for the UEFA Cup due to Schalke already being in the Champions League via league-based success.

Photo: Imago / Kicker / Liedel

Despite the joy of promotion, Union struggled to maintain momentum, and in 2004/05, they were relegated back to Regionalliga Nord, swiftly followed by a further slip down to NOFV-Oberliga Nord (4th Division) the next season. During this period, the club’s financial situation was dire, and its very existence was under threat of extinction.

Many clubs in such administerial crises would crumble, but Union is not such a club – their fans stepped in, starting the Blüten für Union (Bleed for Union) campaign. In Germany, the state pays blood donors for their service, and Union ultras mobilised by organising masses of fans to donate blood, and then transferring their money earned straight into the club. One would struggle to find a more literal example of giving one’s life toward a football club in world football.

Photo: Imago / Contrast

The club gambled on keeping a professional squad for the sole season in the fourth tier, and it paid off as they immediately gained promotion back to the Regionalliga Nord. Come 2009, Union had worked their way back to 2. Bundesliga, where they would spend the next 10 years before finally winning promotion to the top flight last year in an unforgettable play-off victory on away goals against VfB Stuttgart.

It should not go unnoticed that amidst their years in 2. Bundesliga, Union needed to renovate their stadium due to it suffering from structural decline, but they could not afford to hire private contractors to refurbish it. Once again, step forward over 2,300 diehard fans from eclectic cultural backgrounds (men and women of all classes, both with and without construction experience) who volunteered an estimated 140,000 man-hours to rebuild the Stadion An der Alten Försterei.

The Makings of Hertha BSC

Founded in 1892 as one of the founding members of the Deutscher Fußball-Bund (German FA), Hertha Berlin have – for some time now – been Berlin’s wealthiest and most prestigious club. Being on the West side, they enjoyed geopolitical and economic advantages over Union, but Hertha didn’t escape difficulties caused by the Wall themselves.

When the Bundesliga was formed in 1963, Hertha was West Berlin’s champion, and therefore qualified to enter the league as an inaugural member. The following season, they were relegated despite finishing clear of the relegation zone, due to attempts to bribe players to remain in the capital under what had become hostile conditions since the building of the Wall. They managed to gain promotion in 1968/69, which bred stability on the pitch and saw them become the ‘popular’ club of Berlin.

This stability didn’t last too long though; in 1971, there was a league-wide match-fixing scandal which Hertha were found to be involved in. During the investigative proceedings, it was also revealed Hertha were 6 million Marks in debt, and the club had to sell their home ground in order to survive, and consequently played in temporary stopgap grounds they don’t own even until this day.

Photo: Imago

This scandal aside, the 1970s was a fruitful era for Hertha, as they finished runners-up in the Bundesliga in 1974/75, reached the semi-final of the UEFA Cup in 1978/79, and finished as finalists of the DFB-Pokal (1976/77 and 1978/79). Unfortunately, the tides turned at end of the decade, as Hertha were relegated to 2. Bundesliga, where they would spend the majority of the next 20 years.

Club Relations

Immediately following the fall of the Wall, the jubilation between the reunion of East and West was incredible. Two days after its fall, approximately 11,000 East Berlin residents crossed the now-irrelevant border to watch Hertha play SG Wattenscheid. The freedom of movement meant residents of both sides, who up until this point had led very different and separate lives, could now enjoy their shared life for football, and consequently, the bond between Hertha and Union was further strengthened.

Four months after the fall of the Wall, the two teams organised a friendly, and a crowd of just under 52,000 packed into the Olympiastadion to watch Hertha beat Union 2-1. Labelled the Berlin football ‘family festival’ by Der Tagesspiegel, the whole crowd (having paid for their tickets in their respective currencies) sang songs together about reunification.

Photo: Picture-Alliance / Thomas Wattenberg

Fast forward 20 years, and Union’s promotion into the 2. Bundesliga meant that – for the first time in their respective histories – Hertha and Union were in the same division. During preseason, in order to celebrate the fan-fueled renovations of Union’s Stadion An der Alten Försterei, a friendly between the two sides was once again organised. Hertha won 5-3, and for the first time a sense of venom was felt – a rivalry was rising out the ashes of a historic friendship.

Manfred Sangel, a Hertha supporter and radio commentator, recalled in an interview with Der Tagesspiegel that “the [Union] stadium announcer kept having a go at us and one of our players.” The amicable respect for one another that had formed amidst a shared bond over Berlin’s split was finally starting to chip away, much in the same way as the wall had 20 years prior.

The older generation who had lived much of their lives behind the Wall still viewed their opposition as friends, but the Ultras and younger fans were fomenting hatred. In 2011, any doubt that this fixture had become a rivalry was blown out the water when following a Hertha 2-1 away victory on Union turf, Union striker Christopher Quiring stated in an interview with Sport1:

“They cheer in our stadium. That makes me puke! You have to digest that first. I don’t give a shit about my goal. When the Wessis [semi-derogatory term for a West German] cheer in our stadium, I get sick.”

Many people believe that football in the 21st century has lost its bite due to multinational corporations making the sport and its surrounding media more family-friendly, but rather than reprimanding Quiring, his manager – Uwe Neuhaus – described him as a ‘great Unioner,’ doubling down on the newfound hatred for their crosstown rivals.

Come May 2019, Union’s play-off victory over VfB Stuttgart meant that Berlin finally had two teams in the Bundesliga for the first time ever. With the upcoming match between the two teams, Hertha asked the league organisers whether the match could be played on the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

To the average person, this may seem like a touching act of compassion, but to many Union fans, it meant the gravitas of the anniversary outweighed the importance and spectacle of the match itself, leaving them with a sour taste in their mouths. Union’s president Dirk Zingler described the idea as a “football class struggle,” and the match was consequently played a week earlier. The rivalry was starting to heat up before anyone had even set foot in the ground, never mind a ball be kicked.

Photo: Sports News

When the day finally arrived, a different match day experience occurred than anything Berlin had ever seen before. The walk to Union’s ground from the nearest station is through a forest, a placid journey albeit amidst the surroundings of passionate, vociferous fans. The day of the derby, however, this was not the case, as the path was split down the middle by a line of police cars and vans, along with 1,100 riot police patrolling the scenery.

The intensity of the crowd matched the expectations, and in the first half, Union ultras raised not one, but two separate tifo displays, whilst Hertha’s entire away contingent had arranged for its whole stand to don blue and white apparel in order to emulate their club badge. Throughout the match, both sets of fans also burned merchandise and memorabilia that they had stolen from their rivals’ stadia and pubs.

The game itself was a hard-fought battle, with the score tied until Union were awarded a penalty in the 87th minute, which was then converted by Sebastian Polter. This caused a tremendous uproar, with Hertha ultras firing pyrotechnics onto the pitch, some of which deflected into the adjacent Union stand.

Photo: Pixathlon / REX / Shutterstock

The referee, Deniz Aytekin, suspended the match whilst the pyro was extinguished and removed, and the match was then resumed. The final whistle blew, and Union had won their first ever Berlin derby in the Bundesliga, but the insult and potential harm caused by Hertha’s misfiring flares was deemed too much by Union ultras, who started the scale the fences in an effort to confront the Hertha fans.

Luckily, Union goalkeeper Rafał Gikiewicz confronted his own fans and managed to talk them down from the idea – leading to universal praise by fans, players and the media alike in his vital role of avoiding a full-scale riot.

Photo: Getty

Potential violence aside, it is a travesty that today’s match will be played behind closed doors. The prospect of a sold-out Olympiastadion hosting its first ever Bundesliga derby against Union was one of the storylines of the 2019/20 season, and indeed, Berlin’s entire footballing and perhaps cultural history, but unfortunately, we shall be denied the full spectacle due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Prior to the season, I would have asserted that the majority would have expected Hertha to be clear of Union in the table by this point, but today, only a point separates them. Hertha will be desperate to make amends on home soil, and Union will be out for blood so as to pull off the double and stake their claim as the best team in Berlin.

What to Expect from Today

To call Hertha’s season a disappointment would be a severe understatement. Under Ante Čović, they seemed to be totally lacking in both inspiration and identity, and although they showed flashes of improvement under Jürgen Klinsmann, his spontaneous resignation signaled yet another issue for the club to try to resolve.

Bruno Labbadia had to wait two months for his first match, having been appointed as their new manager following the start of Germany’s lockdown period, but last weekend, the wait came to an end as Hertha beat Hoffenheim 3-0. Labbadia could have hardly wished for a better start to his time in Berlin, but upon analysing the match itself, even the most diehard Hertha fan would be foolish to refute the fact the result did not reflect the performance of the respective teams.

Photo: Thomas Kienzl / Pool via Reuters

Hoffenheim’s finishing throughout was appalling (almost certainly due to the lack of sharpness caused by two months of lockdown), with them squandering chances wide from central areas, or in one case, smashing a shot into the groin region of poor Rune Jarstein, the Hertha keeper.

On the flipside, Hertha’s first goal was an absolute gift – Kevin Akpoguma deflected the ball into his own net despite the fact that the shot was going well wide and there were no attacking threats behind him. Their second goal, however, was brilliant. Maximilian Mittelstädt beat his man out wide and whipped in a lethal cross, which Vedad Ibišević headed home.

The third goal was once again questionable though. Matheus Cunha executed an excellent piece of skill to shrug off his defender near the corner flag, ran directly at the goal, before powering a shot past Oliver Baumann into the far corner of the net. While I say ‘past,’ it was more like Baumann dodged out the way; there is no feasible excuse for being beaten at that angle. At the end of the day though, Labbadia’s Hertha had put behind their pre-lockdown woes and secured a vital three points.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66830899/1213177483.jpg.0.jpg)

Photo: Thomas Kienzle / Pool via Getty

Given their small financial stature, Union Berlin have been nothing short of inspirational in their maiden Bundesliga campaign. Having pulled off upsets against Eintracht Frankfurt, Borussia Mönchengladbach, and Borussia Dortmund, there is no question that Urs Fischer has done a fantastic job throughout, and they deserve all the plaudits they have received – with them currently standing 12 points clear of the automatic relegation spots.

They have demonstrated an unexpected tactical flexibility and a cunning ability to adapt to the opponent’s game plan, but regardless of whether they’re pressing with intensity (as they do against opponents of a similar standard) or ceding possession albeit with tight man-marked systems (as they did against Bayern last week), the whole team’s work ethic is of the highest standard, and they put their bodies on the line without any second thoughts.

They play a rather direct style, with the main focus to launch the ball into Sebastian Andersson, and then win the second ball and attack from there. It’s not particularly complicated, but it is effective and has proved hard to beat all season.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65559590/1183597055.jpg.0.jpg)

Photo: Sebastian Widmann/Bongarts/Getty Images

With Bruno Labbadia only having been in charge of Hertha for one match, this is little information to determine what his favoured system will eventually be, but if last week is anything to go by, Hertha will be playing a 4-4-2.

Cunha is in particularly strong form, with his goal in last week’s match taking his tally to 3 goals and 1 assist in his 5 appearances since joining the club in January. His canny off-the-ball movement and ability to beat a man, and then quickly either release a dangerous pass and take a snap shot on goal, will be a key threat for Union, and their über physical defensive assets will attempt to dominate Hertha as soon as the match kicks off, not least so as to intimidate the Brazilian.

Ibišević’s ability to drag defenders out of position to either make space for incoming runners or momentarily find a pocket for himself was particularly impressive against Hoffenheim, and if he can match last week’s performance, Union’s defence will be busy keeping him under wraps from the inevitable Mittelstädt crosses.

Photo: Reuters

Union will almost certainly play their tried and trusted 5-4-1 shape, and they’ll be hoping Andersson will be fit enough to start today as him not starting against Bayern made their lack of depth up front ever so apparent – Anthony Ujah is nowhere near as much of a handful for defenders.

Despite the result, many aspects of their performance against Bayern were highly commendable, and if they manage to implement their man-marking system to the same effect against Hertha, I wouldn’t be so sure Hertha will be able to find solutions to the problem at hand with as much ease as Bayern did. Should Union manage to prevent Marko Grujić from dictating Hertha’s progression from deep, alongside tracking Cunha if and when he drops off from the frontline, the match could end up being a tight affair – much like the first meeting.

With Union having lost three on the trot (albeit straddled either side of lockdown), Fischer will be desperate to find a positive result via whatever means necessary – and I have a suspicion the end result could come down to a singular moment of magic at a set piece, given Hertha’s dodgy defending last week against Hoffenheim and Union’s creativity in freekick and corner routines all season.

For a multitude of reasons, both on and off the pitch, the Berlin Derby should be an intriguing encounter. Being billed by many as the battle of East vs. West, it is wonderful that a city so rich in history and culture finally has a football derby to match rivalries of its international counterparts.

By Greg Bannan

Featured Image: @GabFoligno