How Holstein Kiel Shocked The World and Defeated Bayern Munich

On Friday, January 8, Bayern Munich squandered an early 2-0 lead to lose to Marco Rose’s Borussia Mönchengladbach, a match which saw the defending European champions lose their first match in all competitions since September 27. Bayern looked to bounce back from their defeat five days later, when they paid a visit to Holstein-Stadion to face off against Holstein Kiel in the Second Round of the DFB-Pokal.

Having won two of the past DFB-Pokal Finals, Bayern were widely expected to trounce Holstein Kiel, currently 4th in the 2. Bundesliga. After heading into halftime with a 1-1 score following goals from Serge Gnabry and Fin Bartels, Bayern looked set to be cruising towards the Round of 16 after Leroy Sané grabbed a goal shortly after the break. However, in the last play of regulation, Hauke Wahl headed home a cross from Johannes van den Bergh to force extra time.

Bayern dominated proceedings over the next 30 minutes and came close to adding a go-ahead goal, but the hosts held on and kept the score level. Holstein Kiel would go on to win 6-5 on penalties after Marc Roca’s shot was saved and Bartels converted from the spot. It was a historic achievement, not only for a second-division team to beat the best team in the country, but to manage to dominate Bayern in sustained phases of possession.

Pressing

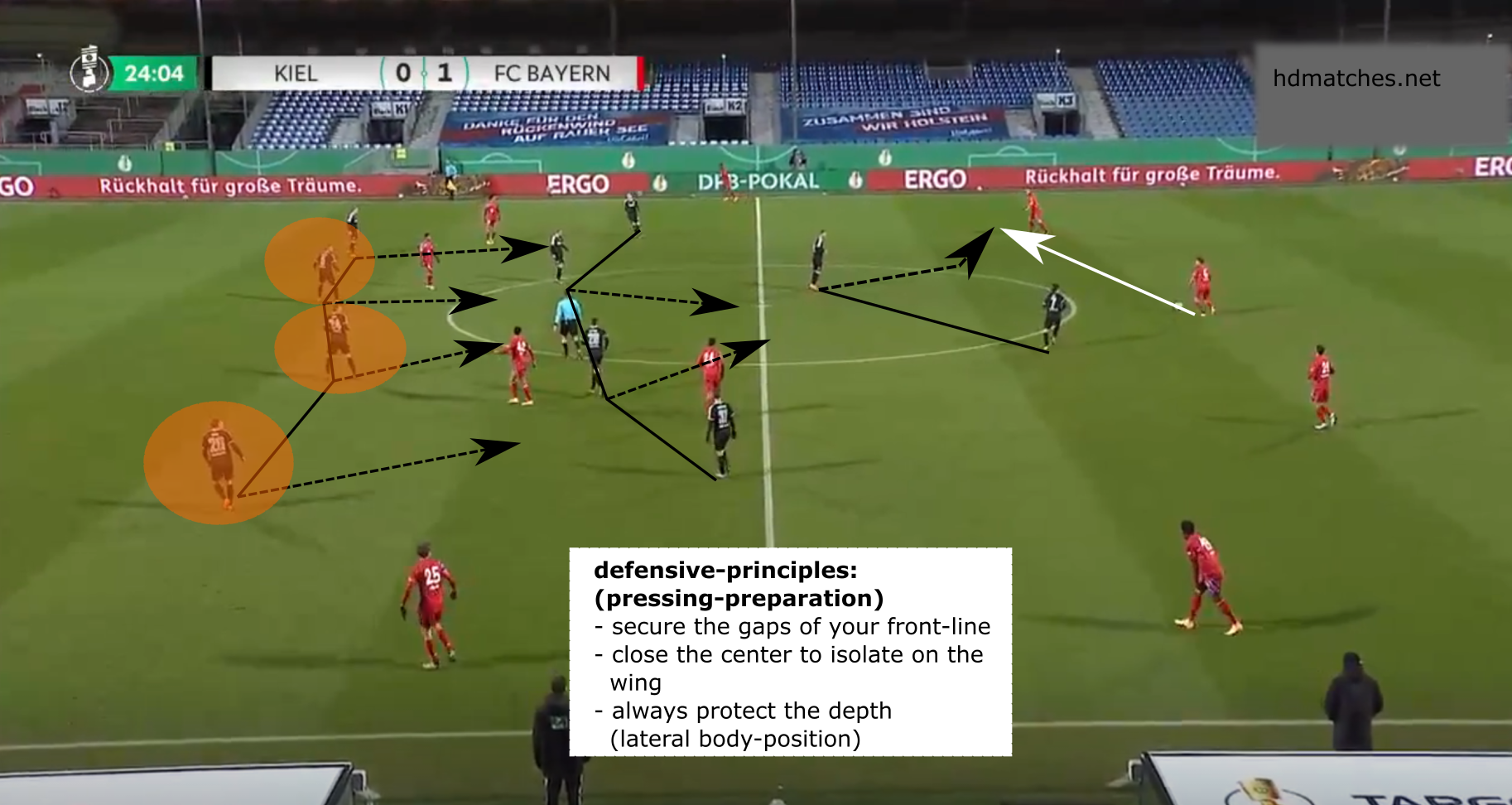

Holstein Kiel defended in a hybrid formation of a 4-2-3-1 and a 4-4-2, often working with slightly asymmetrical structures to direct Bayern to their right side. In the pressing preparation, they were careful to ensure that the centre was not exposed, but they also maintained their intense marking off the ball, meaning that their midfielders had short distances to cover and could tackle their opponents relatively quickly.

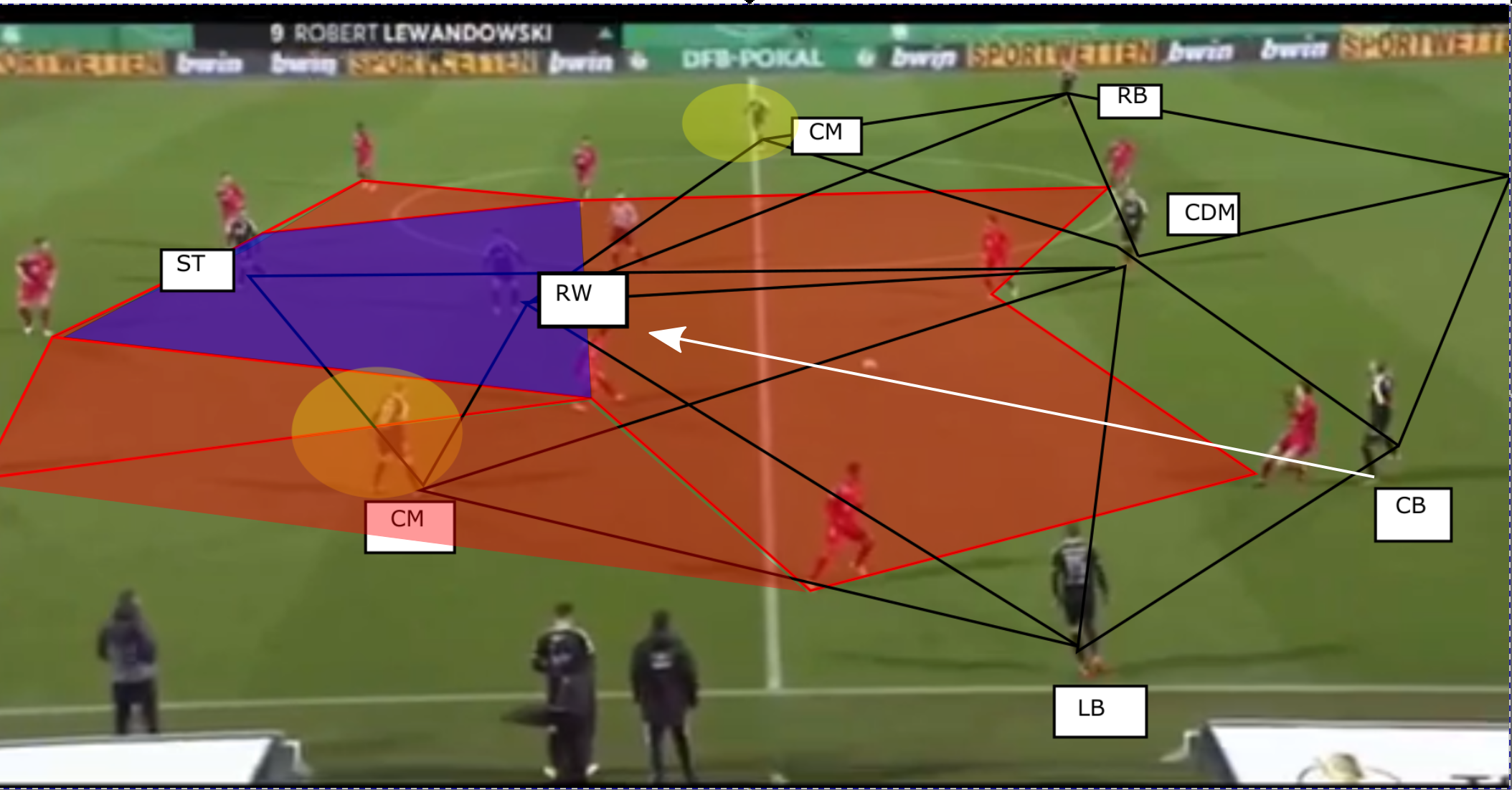

When Kiel managed to force Bayern into wide positions when building out from the back, Kiel looked to aggressively close down all passing options surrounding the full back in possession. In order to sustain this, Kiel’s full backs moved towards a man-marking based system to prevent the ball from being played into Bayern’s winger, whilst Kiel’s central players would mostly look to prevent any space from being found centrally for Bayern.

During these situations, the ball-side striker would aggressively chase back passes to Bayern’s center back. Usually, the free striker would handle Joshua Kimmich by dropping slightly deeper and moving into the midfield. The ball-side central midfielder, in turn, man-marked the next central passing-lane. It was crucial, however, that the central midfielder could maintain the height of the midfield line and did not have to drop too deep or move too far up.

Alternatively, the central midfielder would defend such situations by shadow-covering the space behind him, to close the depth available to Bayern between the lines. For this, it was important that the other central midfielder maintained the gap to his midfield partner, whilst also looking to close potential passing lanes.

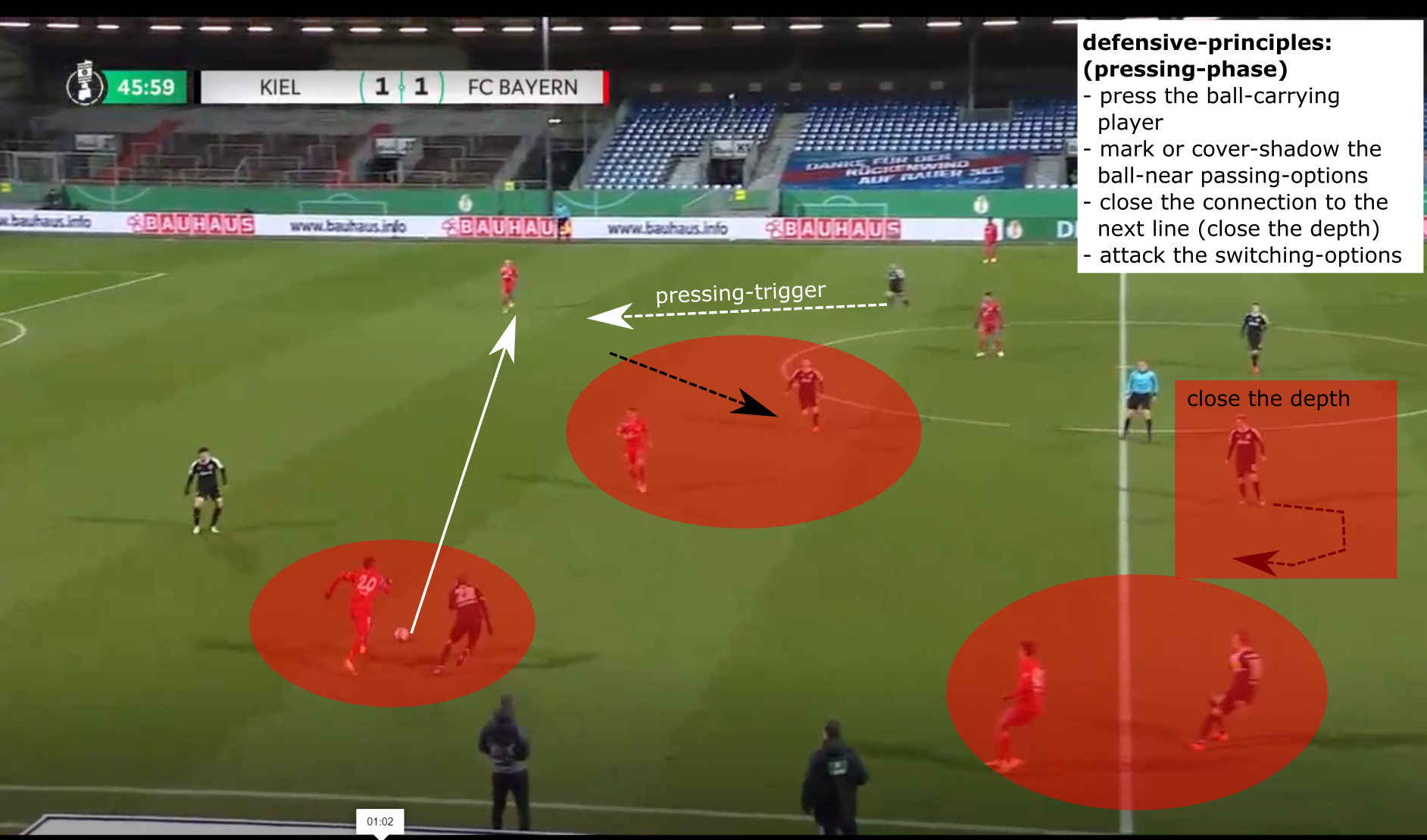

As the only passing-option, Kiel offered Bayern’s full backs the possibility of switching the play to the far side center back. However, this was the pressing trigger for Kiel’s far side winger, who then tried to anticipate the pass, or alternatively, put Bayern’s center back under pressure to force a mistake and a potential turnover. As a result of the large length of the passes Bayern were forced to play, Kiel had more time to apply pressure whilst the ball was traveling, and thus, increasing their chances of winning the ball back.

As the game progressed though, Kiel’s pressing inevitably grew slower and less intensive, especially when Bayern used a back three during their build-up, meaning they were able to overrun the Kiel attackers using the numerical advantage. Additionally, Kiel’s midfielders could not provide support further up, as they looked to stay man-to-man with their midfield counterparts.

This led to there consistently being space for Bayern’s inverted winger whenever their full back stayed wide, and Bayern central midfielders could keep Kiel’s midfielders in the center. From there Bayern would have multiple possibilities to continue the play. On the one hand, they could attack the near-side wing, but on the other hand, they could play the ball through the middle to the far wing.

Alternatively, Bayern could have attacked the half-spaces with vertical balls into the player in space, as highlighted in the image below, showing the multiple different options available to the Bayern center-back in possession once they had progressed beyond Kiel’s initial press.

Positional Play

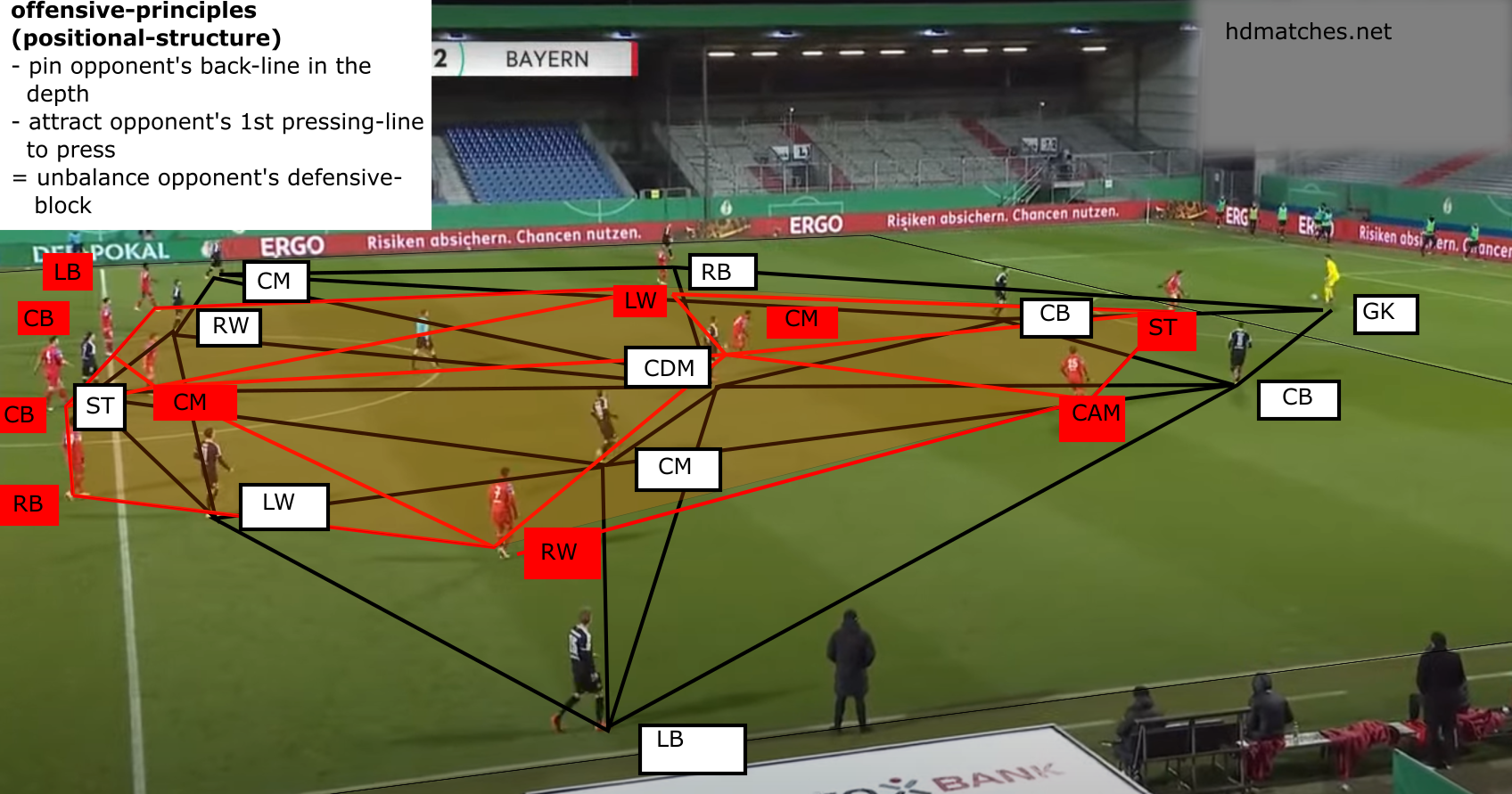

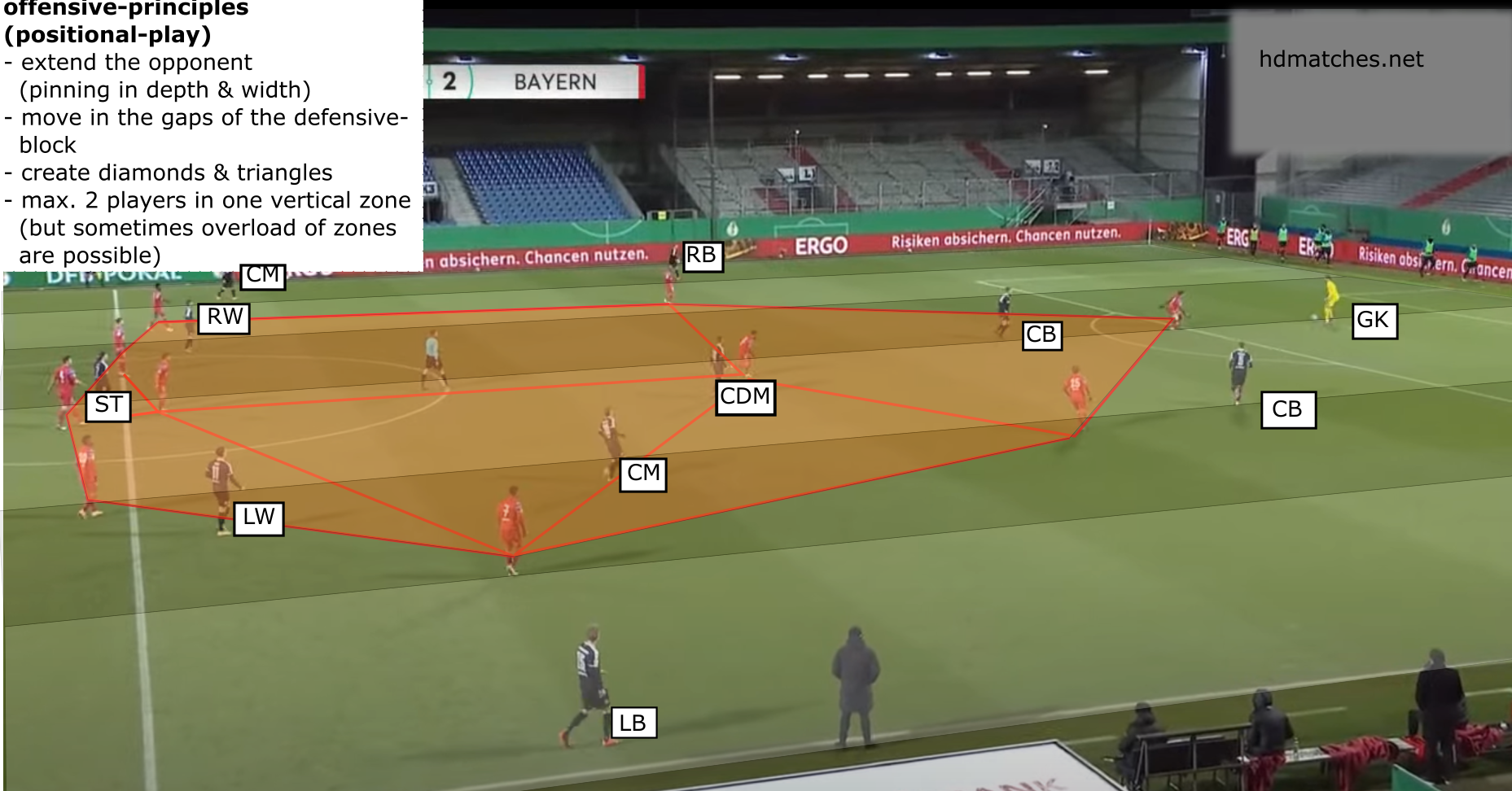

In possession, Kiel played in a 4-3-3, from which they occupied positions on a highly fluid basis. One of the most important principles was to unbalance Bayern’s defensive structure as much as possible. The main way Kiel looked to do this was through maximising the height of their attacks, meaning keeping the defensive and forward banks as far apart as possible. This would mean that Kiel to pin back Bayern’s defenders from pushing too far forward, whilst also essentially baiting Bayern into pressing high, to maximise the space in between the lines.

The most important position Kiel looked to pin back was the full backs, which they achieved by positioning the winger, or in some cases, the central midfielders as high and wide as possible. This is because Bayern’s full backs then had to stay further back to prevent Kiel from having a spare attacker. However, this resulted in Kiel either having more space on the wing, or more advantageously, they could lure Corentin Tolisso or Kimmich onto the wing so that there was more space in the central midfield area.

Throughout the game, Kiel’s coordination in their positional play was one of their great strengths. As a result, they had to pay very close attention to the fact that the vertical corridors were usually only occupied by a maximum of 2 players, who usually maintained good spacing between themselves so as to not attract further attention into the corridor. This led to the potential for positional superiorities by overloading the inside channels at the right time.

Furthermore, the creation of angles for diagonal passes provided an alternate method of progression for Kiel. During the situations in which Kiel could not form sufficient triangles, especially on the side of the pitch that the ball was on, they would seek dynamic movements from players either further back, or further forward, in order to occupy missing positions which could allow for further triangles to be created, and thus, a greater number of opportunities to progress the ball.

Kiel’s players usually positioned themselves along six vertical lines, with the center backs often having an unusually central positioning, which kept Bayern’s initial press quite narrow and thus opened up passing lanes to the wings.

The central midfielders, on the other hand, usually took up strikingly wide positions. This helped them drag Bayern’s two central midfielders as far apart as possible, and to additionally provide potential overloads on the wing as a result of Bayern’s full back being pinned down as mentioned earlier. However, only players who were not pinning down other Bayern players could enter into the space creator centrally, otherwise, one of Bayern’s players could push further forward to increase the pressure on the ball and occupy the space.

For example, Kiel’s winger was only allowed to go into the center, if at the same time the central midfielder was able to pin down Bayern’s full back, ideally as wide as possible. The same applied to the striker, who could only drop into the midfield if one of the wingers or central midfielders ensured that the opponent’s center back could not follow the striker, and put pressure on him.

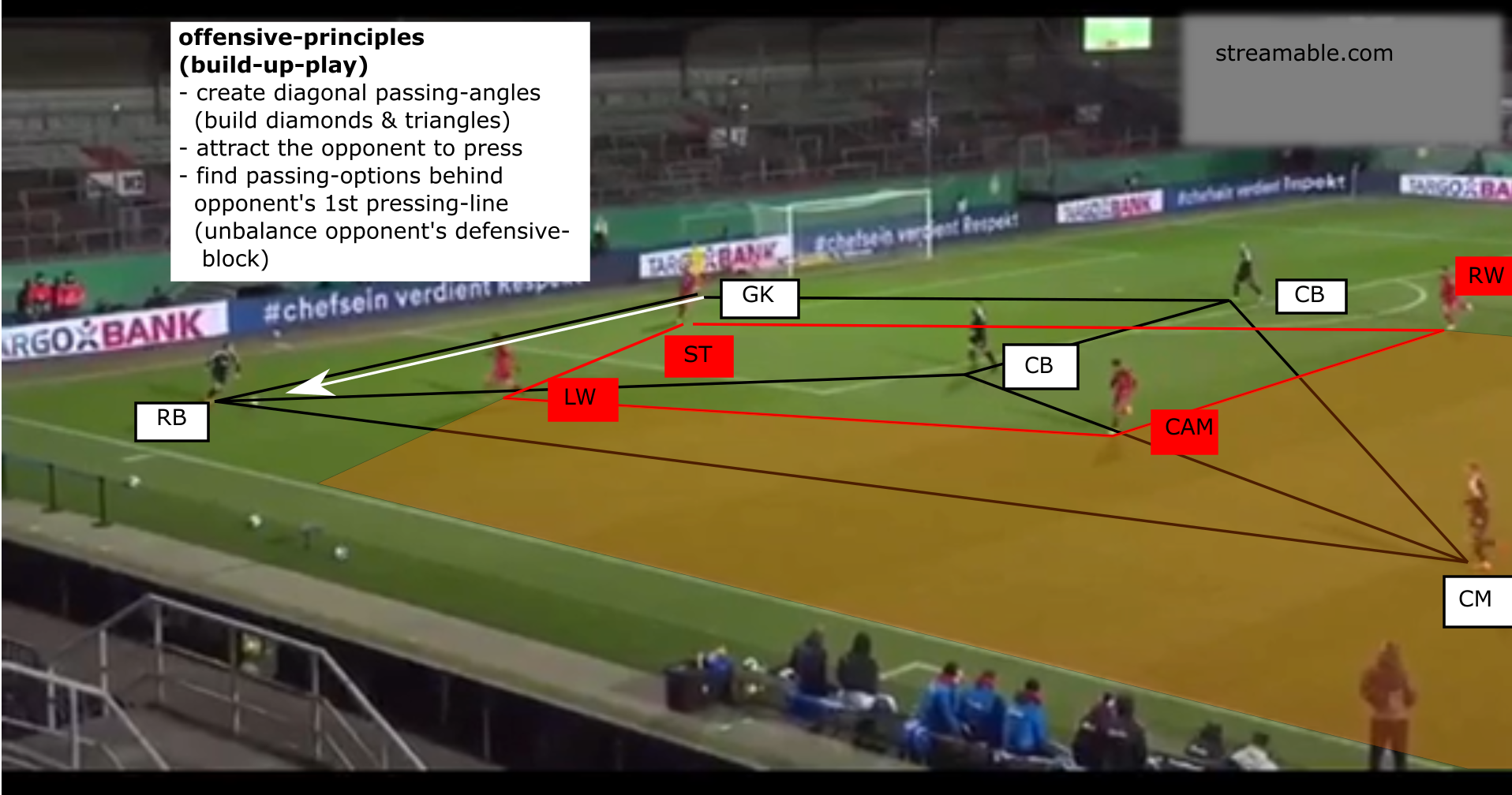

Simultaneous to this pinning back of Bayern’s deeper players, Kiel consistently looked to utilize positional rotations. These aided specifically against Bayern’s loose man to man approach in order to create space. Again, it was the center backs who held the key with their role, in which they sometimes quite unusually pushed into the defensive midfielders area, to form somewhat of a diamond with the goalkeeper, and the ball side full back.

This structure meant that either Bayern’s winger then followed the deeper full back and so there was more space for Kiel’s overloads on the wing, or that Kiel had more time during the first phase of building out, as the pressing path of the striker had grown.

The role of the center backs was at times reminiscent of Kiel’s interpretation under Tim Walter, who managed the club from 2018 to 2019 before taking a job with Stuttgart, when they worked with an extremely large number of rotations in the first phases of building. However, it should be noted that under current coach Ole Werner, the rotations of the center backs are more situational, and less extreme than two years ago.

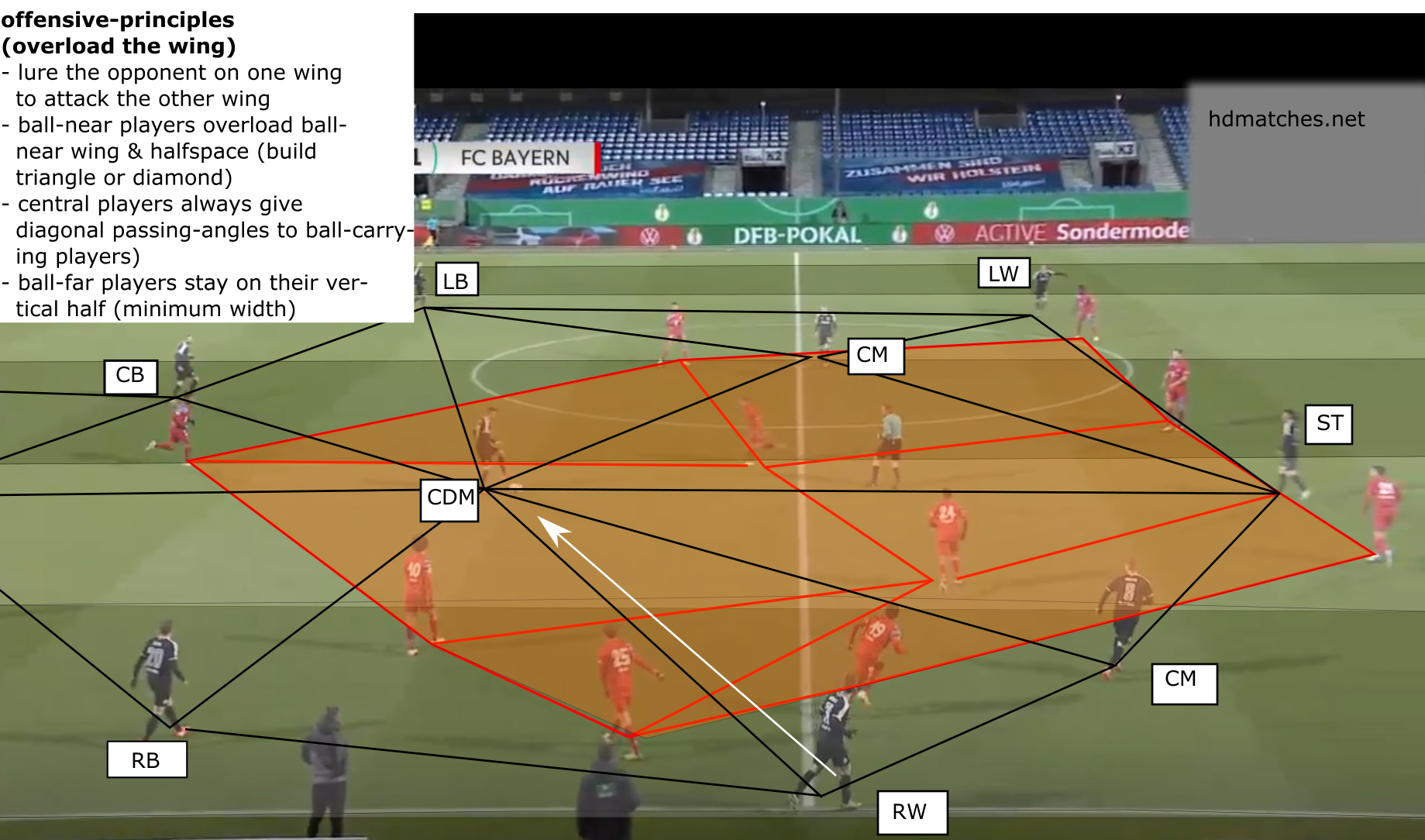

Another key to progress the ball for Kiel was switching the ball. Kiel often started their build-up play through dropping their full backs deeper, in an attempt to bait Bayern into pushing higher up. They would look to keep the far side full back further up the pitch, and thus, one of the central midfielders could go wide on the ball side and maintain the width of the pitch.

However, once Bayern began pressing, it was important for Kiel, that the ball did not stay on this side. Since Bayern’s block had pushed far to the ball side wing, the space available was on the far side, and so, Kiel aimed to get it into this space as quickly as possible.

For this, Jonas Meffert played a crucial role in the pivot position as he was tasked with offering a diagonal passing angle to the space on the far side, meaning he essentially acted as the link between the left and the right sides of the pitch. If Meffert was man-marked, he usually fell into Kiel’s defensive line, with one of the center backs usually stepping up into midfield to ensure the area was not left deserted.

Also important was that now the ball-far winger switched from maximum width to minimum width, so that he could start runs into the back of Bayern’s CB’s. The maximum width could be neglected for a short time, as there was no possibility for Bayern’s FB to push forward anyway. Otherwise, the CM or the FB could occupy the winger’s position.

Importantly, Kiel’s winger would look to come into the half-space once the ball had been switched to provide a passing lane between two defenders and give Kiel a chance of transitioning as quickly as possible to make use of the space created.

Conclusion

Holstein Kiel were certainly afforded some luck to get into the penalty shoot-out in extra time. Nevertheless, it was a highly remarkable performance by the second division team, who displayed their innovative and unique style of positional play. However, as the game progressed, the pressing became more and more laboured, and thus larger spaces appeared throughout the second half particularly, which also caused difficulties in wide areas.

Nevertheless, the positive aspect predominates: despite their qualitative inferiority as a second-division-team, they were able to keep up with the current Champions League winners very well at times. In doing so, they did not have to change their playing-philosophy. The game was most certainly a tactically interesting affair, and Holstein Kiel will be looking to replicate their feat against Darmstadt in the following round of the competition on February 2.

In their 120 years of history, Holstein Kiel have never played in the Bundesliga, and for the bulk of the last decade, they were yo-yo-ing between Germany’s third and fourth divisions. However, Die Störche currently sit third in the 2. Bundesliga — just four points off first-place Hamburger SV — and they will be looking to use their historic achievement as motivation for the home stretch of the season.

By: Darius Schwering

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / picture alliance