Introducing: The Double False 9

The clock has just ticked over 20 minutes and Real Madrid’s centre back partners Sergio Ramos and Raphaël Varane are finding themselves in a rapid whirlwind of calculations. Kevin De Bruyne and Bernardo Silva had both been positioning themselves within reach for quite a while, but it was only now that City were able to properly feed them the ball. A quick play from İlkay Gündoğan to Bernardo Silva had created a paradox of instincts in the center backs’ minds. Should they approach or should they stay back?

After some quick interchanges on the right side, City once again found one of their dropping strikers in free space, this time De Bruyne, and Varane now decided to take his first option, to approach. However, just when he placed his first steps forward, the creative Belgian fed the ball in behind to a leaping Gabriel Jesus. The French centre back could only declare defeat as he witnessed the Brazilian striker free on goal.

This was all a recall from the first of two rounds of sixteen games in the 19/20 Champions League’s season between Real Madrid and Manchester City. Although the Brazilian striker eventually missed the opportunity, this moment was the start of a chain of events that would mainly decide the outcome of the match, but also echo throughout Europe’s tactical spectrum.

Pep Guardiola had, during the season, witnessed Real Madrid’s centre backs’ willingness to apply pressure on players in front of them, and his general idea was that by deploying two players roaming in close contact with them, he would be able to cause uncertainty and disruption in Real Madrid’s defensive line. By doing so, he was also reinventing the use of the false 9 role that had proven to be so fruitful for him in the past.

Since then, fragments of this approach have withheld in Europe, and different versions are becoming ever more present for advocates of positional play. We will in this text further examine the increased use of the approach within this concept, and how fragments of the traditional false 9 is present in the modern game. Before we start, however, we must therefore further clarify two things. What exactly is positional play and what really is the role of a false 9?

The Nature of Positional play

To summarize it broadly, positional play is the idea of players assigned to different zones when in possession of the ball. Emphasis is put on placing players between opponents, often occupying half-spaces and playing behind the opposition’s defensive lines. In this concept, the ball is mostly kept on the ground with short interchanging passes, consequently trying to build out low from the back.

Of course, most systems within this approach are far more complex. For some, the idea of dividing the game into different phases can work as a theoretical tool to clarify the objectivity of the use of the ball. Say you exist in Phase X and want to go to Phase Y, you then need a systematic approach on how to get there. The manager can then plan different approaches to different situations. You might want to use X amount of players in your build-up, but attack with Y amount.

The exact use of your system is then easier to dissect, and is helpful for us when looking at latter specific attacking approaches, as in this text. With that being said, the same system might apply to various phases within the game. In addition, all of the teams that will be further examined are also keen on using countermovements to avoid a stagnating progression.

The Concept of the False 9

The concept of a false 9 is essentially a forward dropping deep. The player does this in the purpose of disrupting lines and creating disorganization, which is fundamental to positional play. The essence of the role is therefore built on provocation.

A forward with this task at hand has been used for decades. Austria’s national team in the 1930s, known as the “Wunderteam”, played their striker Matthias Sindelar in a similar role. In modern times, mainly two great players come to mind, Francesco Totti and Lionel Messi. Totti was used in this type of position in Roma, during Luciano Spalettti’s successful first stay at Roma. Messi played in a similar role under Pep Guardiola in Barcelona.

The Modern Usage

Even though the false 9 often provides two outcomes in which the attacking team can usefully exploit either of them, the deployment of this role in the past was justified in a sense of frequently getting their biggest talents on the ball. For example, apart from Totti’s obvious technical abilities, Spaletti described him as a master in occupying space. Therefore, it made sense to create an environment in which the team could optimize these two great strengths of his.

As seen later in this century, one lone player dropping deep does not always provoke defenders enough to leave their position. Mainly great talents like Totti and Messi attract enough attention to do that. Of course, some players come to mind that have played in a similar role more lately. Roberto Firmino in Liverpool is one example. He is however dependent on wingers playing more centrally, and in Liverpool, the fullbacks are often the ones providing the width. This means that Firmino is able to roam in a system where other players in his team are engaging the center backs and spreading the opposition’s lines.

Yes, Kai Havertz was also briefly used in this role under Peter Bosz during the 2019/20 season. But Havertz, although undeveloped, possesses similar attributes to that of Totti and Messi, and in a surrounding with quick wingers running in behind, forcing teams to drop lower, it allowed him to thrive. He is also quite fast himself and the duties of his role were widespread since he was also making runs in behind the defense himself.

Since a lot of teams now also play with three centre backs,or a midfielder slotting in just between two center backs, like Marquinhos under Thomas Tuchel, the use of a lone striker dropping deep is also limited. A pairing of three centre backs will either not bother to approach a forward dropping deep, or if one player does so, he still has two players covering his ground. Two attacking players, however, will possibly engage more than one defender and therefore cause disruption in the lines.

There are some trends for managers trying to implement ideas from the positional play at the. Great minds like Thomas Tuchel, Pep Guardiola, and Erik Ten Hag all seem to be heavily reliant on leaving the wingers wide and high, to stretch the play but also provide depth pinning the opponents’ backline down. This puts great emphasis on the tactical understanding of the wide players, who then are mainly the ones exploiting spaces behind the center back if they apply pressure centrally and therefore disrupt the shape of the defensive line. A player that does this very well is Sterling, as you will see further down in the text.

Another key aspect seems to be to not overload with players between the opponent’s midfield and defensive line. This is built on the concept that if you want to reach a certain space, let it remain empty. This differs from the use of a normal 4-2-3-1. In this scenario, most managers tend to invert their wingers meaning 3 players are playing centrally behind the strikers.

This often leads to the defending team overloading their defensive positioning with players in the middle. This then leads to the attacking team more frequently having to attack down the wing because that is where space is. Teams like PSG under Thomas Tuchel instead like to remain low with one more player when attacking high, leaving a 2-3 or 3-2 system deep. This gives the teams defensive solidity but also frees up space when attacking centrally.

Today, a maximum of 3 players in the central area, behind the opponent’s midfield line, seems to be the go-to rule for a lot of managers. From here on, teams of course use a variety of ways, but we will just focus on the double occupation of the opponent’s center backs, and the use of a provoker in the free space. This man, as you will see, is either an additional spare man, which is also a common theme in positional play or one of the players playing within reach of the center backs dropping off.

The Usage of Double Occupiers

The night in Madrid featured two strikers in Bernardo Silva and Kevin De Bruyne, both prone and instructed to search for the ball deep more often. Since they were the last attacking line centrally, it essentially meant that City were playing with two false 9s when these two positioned themselves to receive the ball.

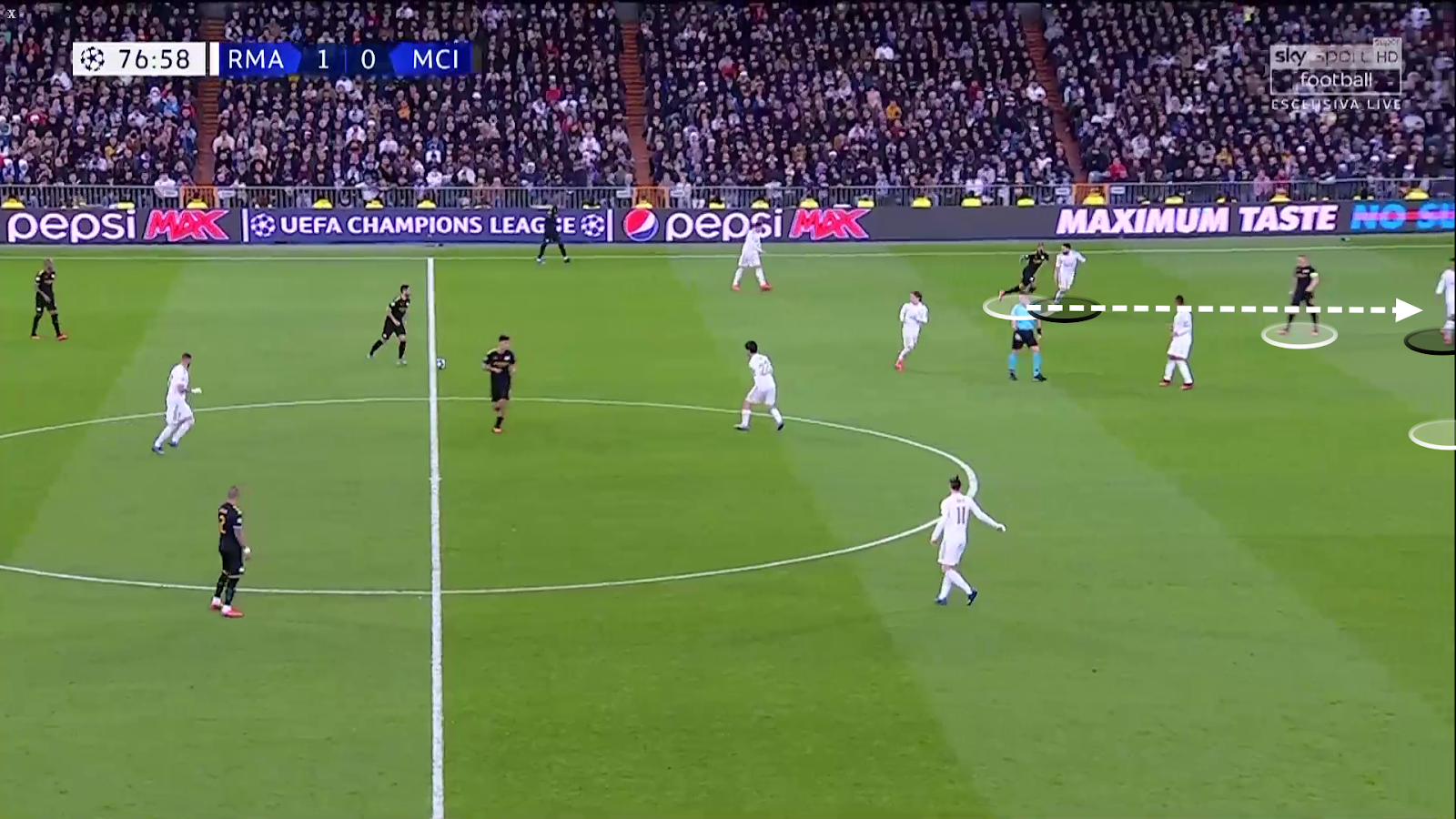

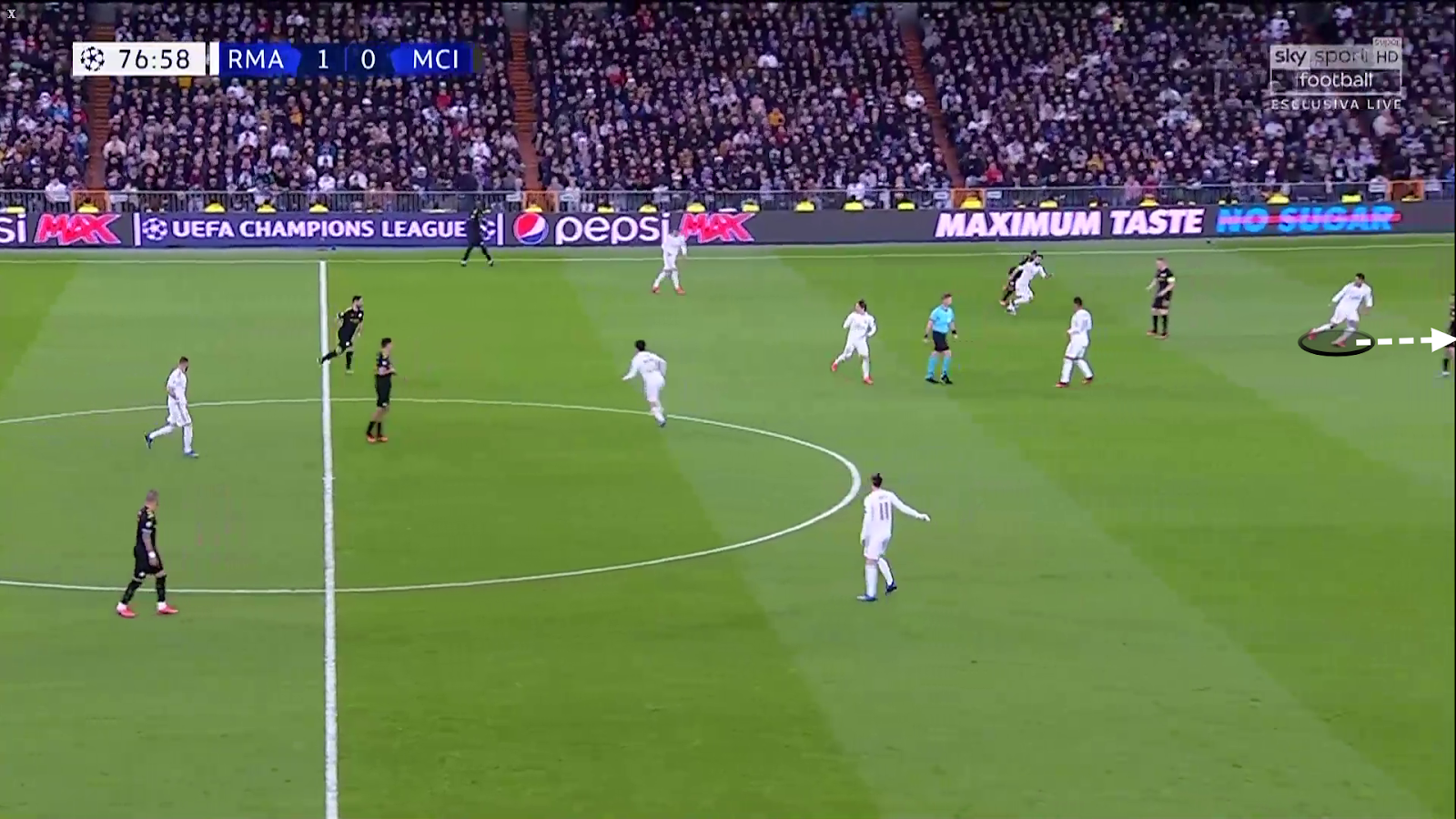

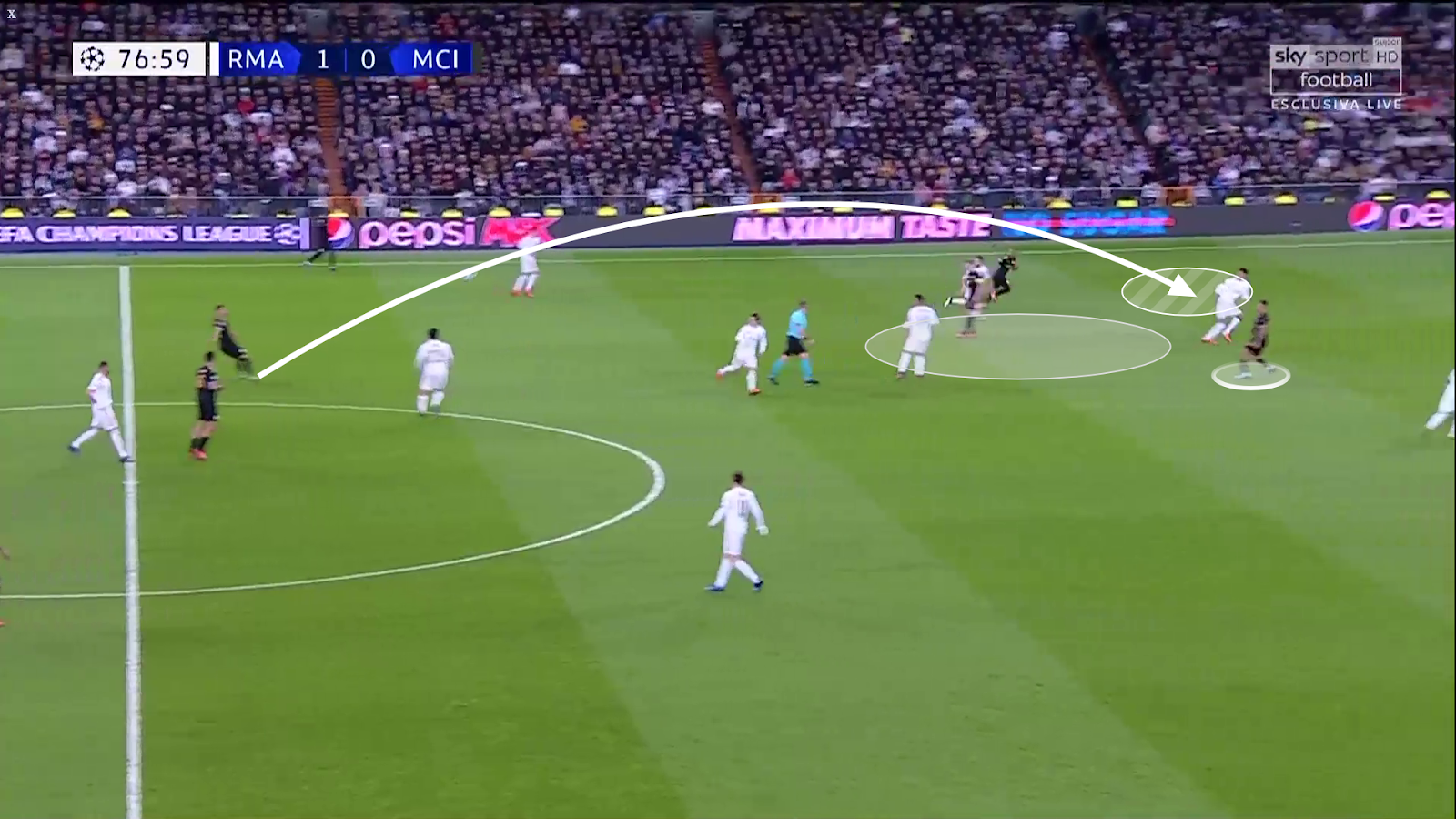

When searching for the ball, Guardiola also wanted both players to drop diagonally to occupy the half-spaces. By their positioning, they were not only dragging Real Madrid’s press happy center backs up the pitch, but also wide. When well positioned, even the defending fullback could be triggered into applying pressure. Either the outcome, City’s winger will be free of space to exploit as seen in the example below.

Here City wins back the ball deep in their build-up phase and has just established a well systematic arrangement on the left side. De Bruyne is first of all positioning himself in the half-spaces, meaning that without any other movement, Varane still has to be dragged wide out of position if he decides to put pressure on the Belgian.

Gabriel Jesus, who is just outside the picture on the left side, is also contributing, due to him also occupying free space centrally. Within a given second Raheem Sterling makes a run deep. Since Dani Carvajal is first unaware of the movement, he ends up on the backfoot, lacking behind Sterling.

This instead forces Varane to follow Sterling’s movement, and therefore allowing De bruyne the free space. Since the run is so precise and well executed, Sterling will soon also be in a position able to receive the ball.

In the end, Gündoğan decided to play the deeper ball to Sterling, and after some sequences, Gabriel Jesus were able to head home 1-1 to the away team. However, with this movement City provided two good options to Gündoğan in the start, and either alternative was in real possibility of hurting Madrid.

Positional Interchanges

Right now City plays a somewhat evolved version of this system. As seen in the picture below, Foden or Bernardo Silva (Bernardo in the example below) often remains as the player providing width on the left side. The fundamentals of two attacking players playing in front of the central defenders is still there, which in this instance below is Ferran Torres and De Bruyne.

In this setup though, Torres is firstly tasked with providing space for De Bruyne, in order for City to frequently put his great abilities on the ball into action. We will further examine that in just a bit. On the right in this system is often Mahrez, but this player often switches with the two central attacking players to keep the fluidity. Gündoğan’s role is often more that of an advanced central midfielder, often arriving late as an additional spare man. As already mentioned,

The difference to their approach in Madrid and now is that City’s main objective more often revolves around finding De Bruyne in free space in front of the backline. This means that City’s frontman Torres is firstly tasked with roaming behind the backline to constantly drag down the central defenders. However, for the system not to become too stagnated, interchanges and countering movements between players must occur in order for the game to stay fluid.

This underlines that within a two striking setup both strikers must be good enough on the ball in order for the game to remain fluid. Let us dive into an example of this below.

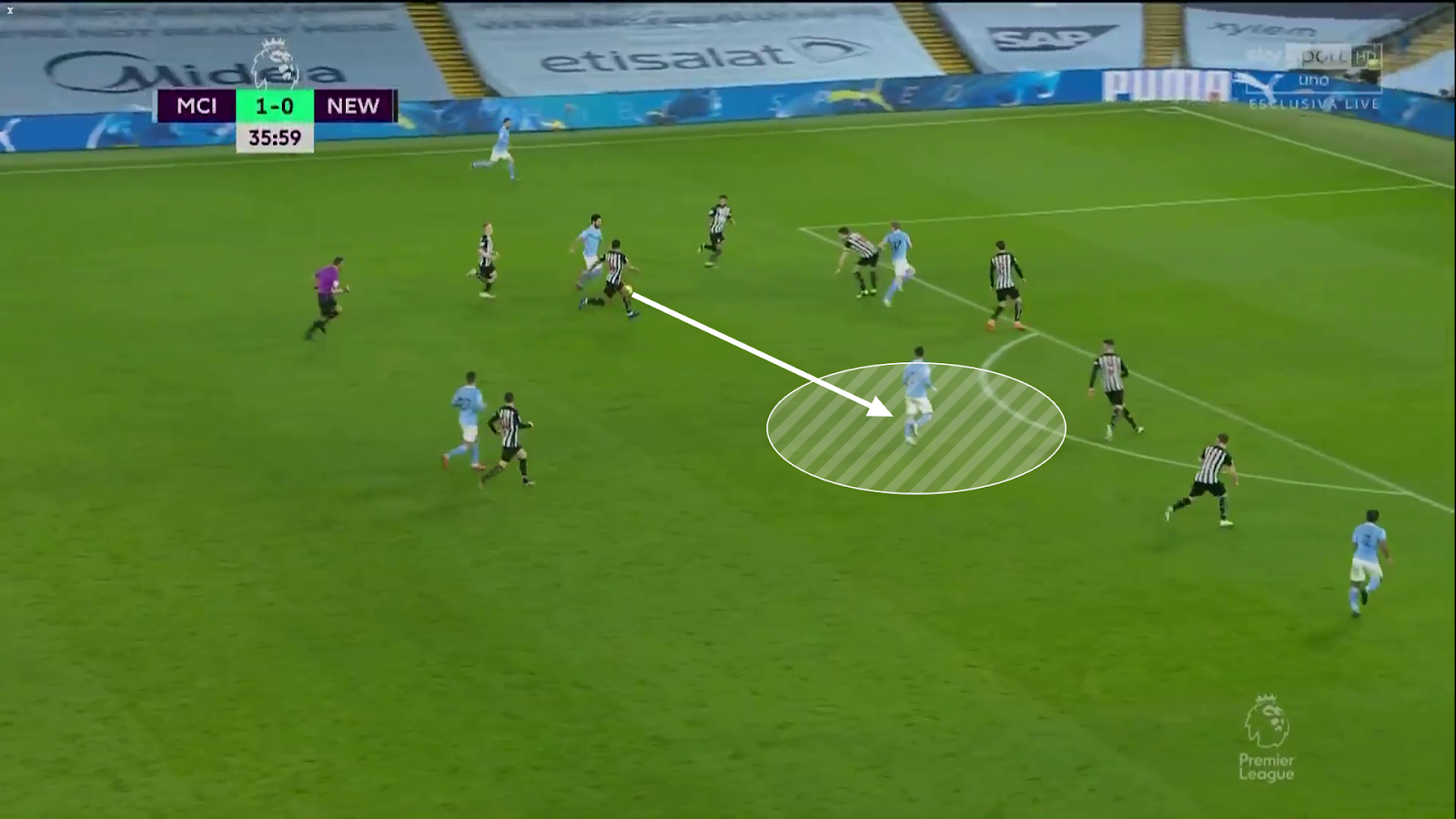

In the first picture City’s usual striker setup is visible. Gündoğan is progressing the ball forward in the middle. De Bruyne has positioned himself a bit deeper away from Newcastle defenders. Torres is here dragging one center back down with his continuous movement forward.

In the second picture, however, De Bruyne makes a run behind City’s defenders, forcing Ferran Torres to slow his run down.

Because of De Bruyne’s run, Torres is able to play one on one with the defender closest to him, and due to CB not daring to follow him, the Spaniard ends up in free space to receive the ball. A couple of sequences later City had scored, and this was the key moment in that attack.

Moving eastward, we can find another club that use a variety of the concept of two players occupying the opponent’s central defenders with Erik Ten Hag’s Ajax. Similar to City, these players are mainly tasked with different duties. However, Ajax line up with more of a clear fixed point, which in the instance below is Lassina Traoré. This player often remains at one center back and is tasked with tying up this player. Left of him is Zakarya Labyad positioning himself. He is in this system the provoker and is tasked to position him in half-spaces, especially in contact with the free center back.

This asks questions to the remaining defenders. In the first instance, with one center back tied with Traoré and the other player unwilling to approach Labyad, the player will find free space centrally, able to receive the ball between the lines. Labyad can also exploit spaces behind the backline if the central defenders become too occupied with Traoré.

On the contrary, pulling out one center back to press Labyad will first of all disrupt the opponents’ last line, but also leave Traoré one on one with the defender. The concept therefore also provides an opportunity for strikers physically dominant, to repeatedly be put in a position where he can utilise his strengths one on one against a lone center back.

With the arrangement of two players within reach of the opponent’s center back, Ajax, just like other teams, then likes to use the addition of a spare man. This player is supposed to arrive late, after the establishment of the fixed point and provoker (Traoré and Labyad). By doing so, Ajax avoid their game becoming too stagnated. It is especially of good use when playing against a double centre back pairing, since the addition of the spare man will almost certainly cause a numerical overload.

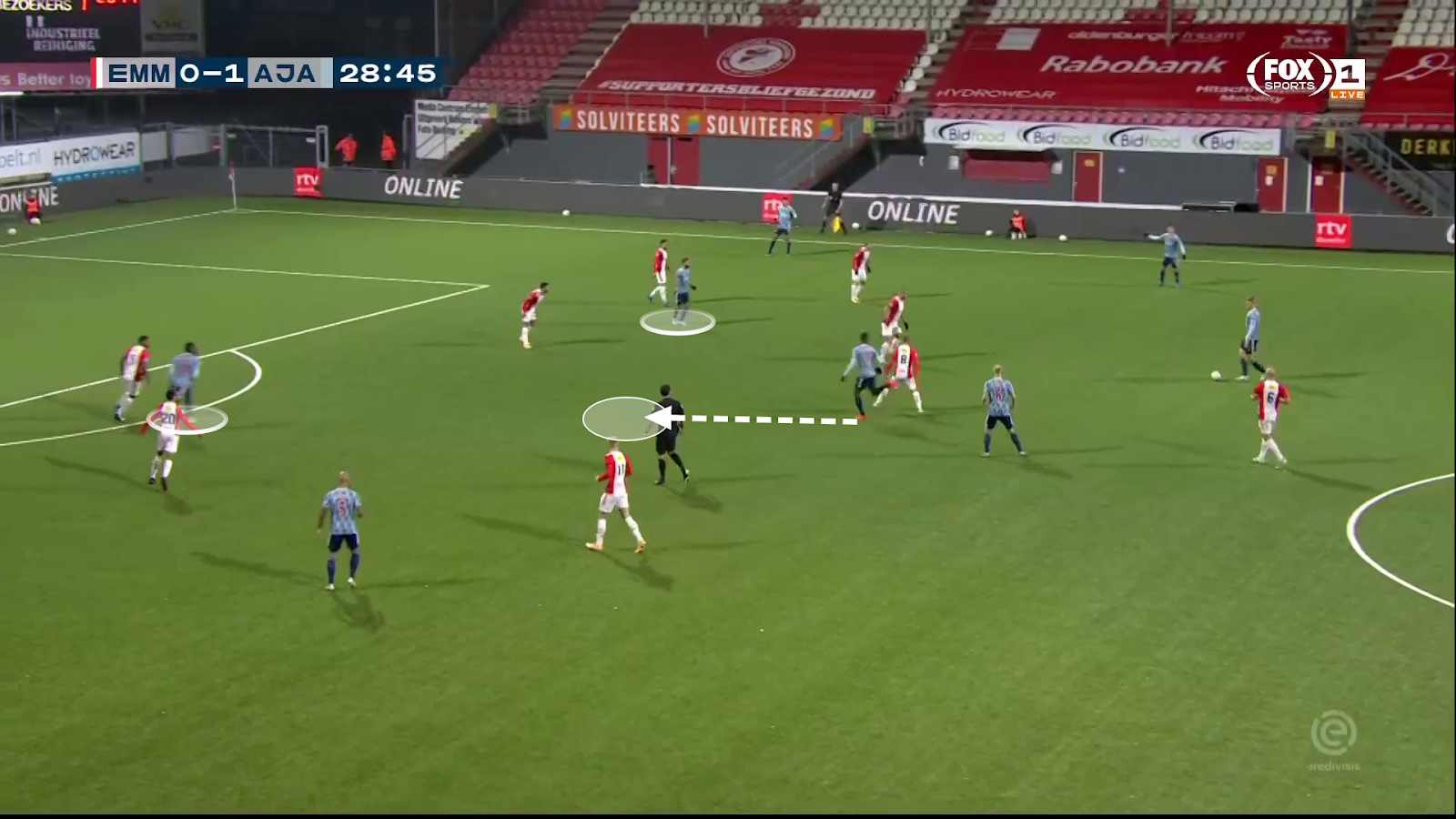

In this example against FC Emmen, Ajax have already established a good attacking setup. Traoré has tied up his center back and Labyad is positioning himself in the half-spaces. Ryan Gravenberch is just on his way to arrive in the free space as the spare man.

After the addition of Gravenberch, Ajax has now caused a numerical overload against the opponents. The left center back now has two attacking players surrounding him, and since he is too occupied with Gravenberch, Labyad makes a run in behind. The Emmen left back does not follow Labyad’s movement. Although the left center back is quick to react, Davy Klaasen’s through ball is too precise and Labyad will soon score.

Moving back to England, Thomas Frank’s Brentford have also been using a similar approach lately. Since the switch from Ollie Watkins to Ivan Toney in the lone striker role in the summer, their frontman has not declined in goal production but is more of a distinct box striker than his precursor. With Toney still possessing good qualities in the link-up play, Watkins was even more astute in his abilities to drop deep and combine with short interchanges.

As such, it makes sense that Saman Ghodoos has been deployed just behind Toney lately. However, the set up is a bit more fluid than Ajax and City. Toney is still instructed to drop deep at times and Ghoddos is allowed to seek the ball over bigger areas. They also switch between having one or two provoking players below the fixed point, instead playing with two players occupying the central defenders and with one additional provoker.

Brentford also seems to like to use the addition of a spare man. The right winger Bryan Mbuemo is sometimes instructed to stay centrally within reach for one center back, with Toney also remaining in a high position centrally. This provides an opportunity for Ghoddos to remain free in space in front of the two. However, Ghoddos is often early positioning himself in the free space, not arriving in a later moment, and the emphasis is instead put on the two strikers, Toney and Mbuemo, to create movement.

Here Mbuemo and Toney is playing close to the opponent’s center back, and countermoves to cause disruption in the defensive line. Toney is dropping and Mbuemo moves in behind, both tying up one opponent each in the process.

This leaves Ghoddos further free of space. In the end, Brentford’s center back Mads Bech actually decided not to play the ball into Ghoddos, but it was a good alternative nonetheless, and showed how Brentford worked to create space within the final third.

Conclusion

Finally, I want to clarify that football is a complex game. Most teams use a variety of approaches from an ever-switching turmoil of coaches responding to different tactical concepts. Players also find solutions that no one has thought of, so of course, this notion is more about when and how teams deploy this approach, rather than always attacking this way.

A portfolio of wide attacking varieties only further widens the uncertainty of how to respond from the opposition, and this is why great minds like Pep Guardiola or Erik Ten Hag are constantly trying to develop the game, and create disruptions within the opponent’s lines to exploit. However, as already mentioned, it is still a concept that has gotten more of a foothold lately, and as we have further examined, there are reasons for that. So, at that night in Madrid, maybe Sergio Ramos and Raphaël Varane were the first to come across the efficiency of this method, but they were certainly not the last.

By: Marcus Ejerblad / @marcusejerblad

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Dean Mouhtaropoulos / Getty Images / Pool – Getty Images