Tactical Analysis: Cycle Over Division

Football is often divided into the ‘four moments’ (in possession, out of possession, attacking transition, defensive transition) as a framework for analysis, however, by doing this, are we ignoring the complex, fluid nature of the game? Watching and analysing Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli (17/18 especially) and Italy at Euro 2020, alongside reading the intriguing Pep Confidential, has allowed me to view this matter from a different perspective.

In essence, it has allowed me to recognise that these elements of the game (often referred to as moments) are all connected, rather than separate, and therefore dividing them up to provide analysis with an element of structure is potentially more ignorant than beneficial, as it disregards the significant relationship(s) between these components.

This was perfectly summarised by Thomas Tuchel, when explaining his coaching methodology at Chelsea, during a post-match press conference after an FA Cup fixture last season; “We spend very few minutes and moments in training isolated on defence or attack. We train in complex situations because the game is complex and we don’t try to divide the situations in an artificial way.”

Tactical Analysis: The First Weeks of Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea

This article will focus on how these elements are connected, by analysing the overlap between defence and attack, and how they both can facilitate advantageous transitional moments. Overall, it will look to explain why we should seek to analyse football wholly, hence the title of the article: Cycle over division.

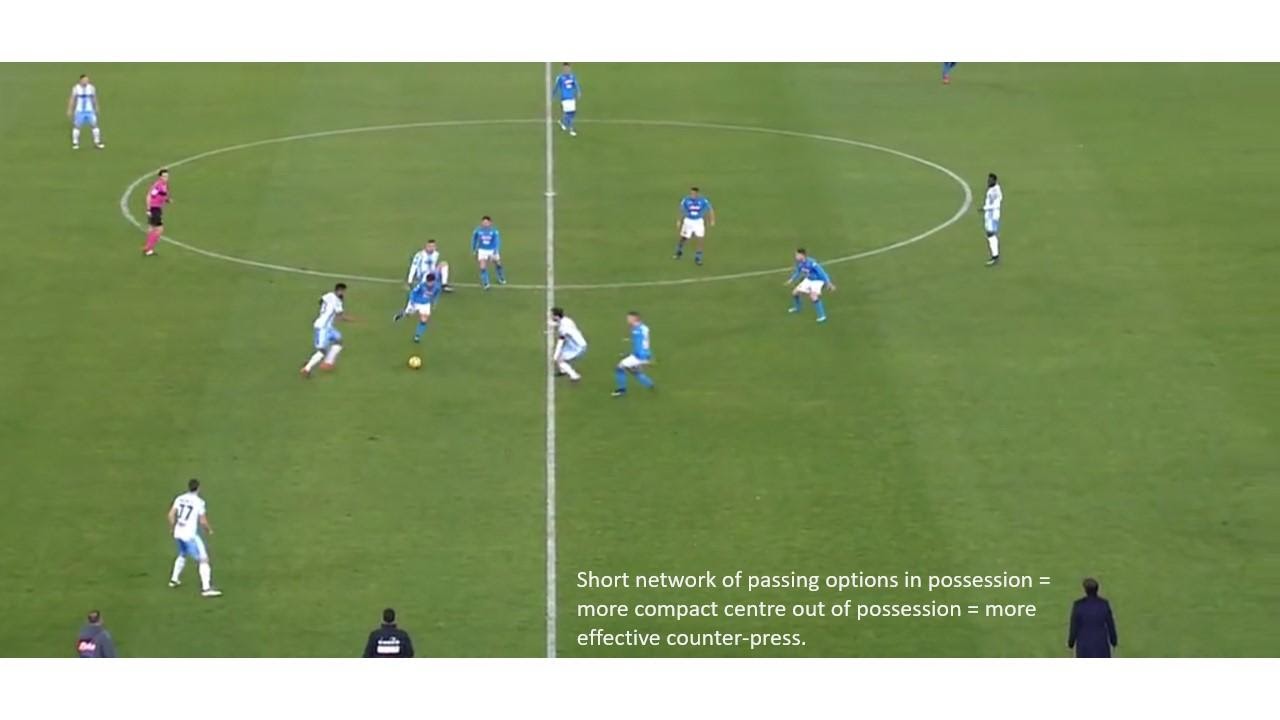

Firstly, the article will focus on defending, or being set to defend, whilst in possession. The general idea is that a more compact centre of the pitch in possession is ideal preparation for a potential turnover, because in turn, it results in a compact centre when possession is lost, which increases the threat of the counter-press because immediate pressure can be applied to all nearby passing options in a shorter space of time, therefore generating a greater chance of turning over the original turnover (winning possession back immediately after losing it).

The 15 pass rule, which stars in the book Pep Confidential, strongly manifests this principle. Guardiola believes that making 15 passes whilst in possession allows the team to move up in conjunction and therefore create central compactness which helps establish control but also an advantageous transitional moment if the ball is lost.

In addition to this, the 15 pass rule also considers the impact on the opposition: 15 passes will force the opposition to become disorganised as they try to win possession back, by pressing aggressively or defending zonally. Consequently, this disorganisation can have a constraining effect when a turnover occurs, as the player who wins possession back is immediately isolated and surrounded by the now defensive team’s central compactness and aggressiveness, which makes the transition to attack a more difficult process.

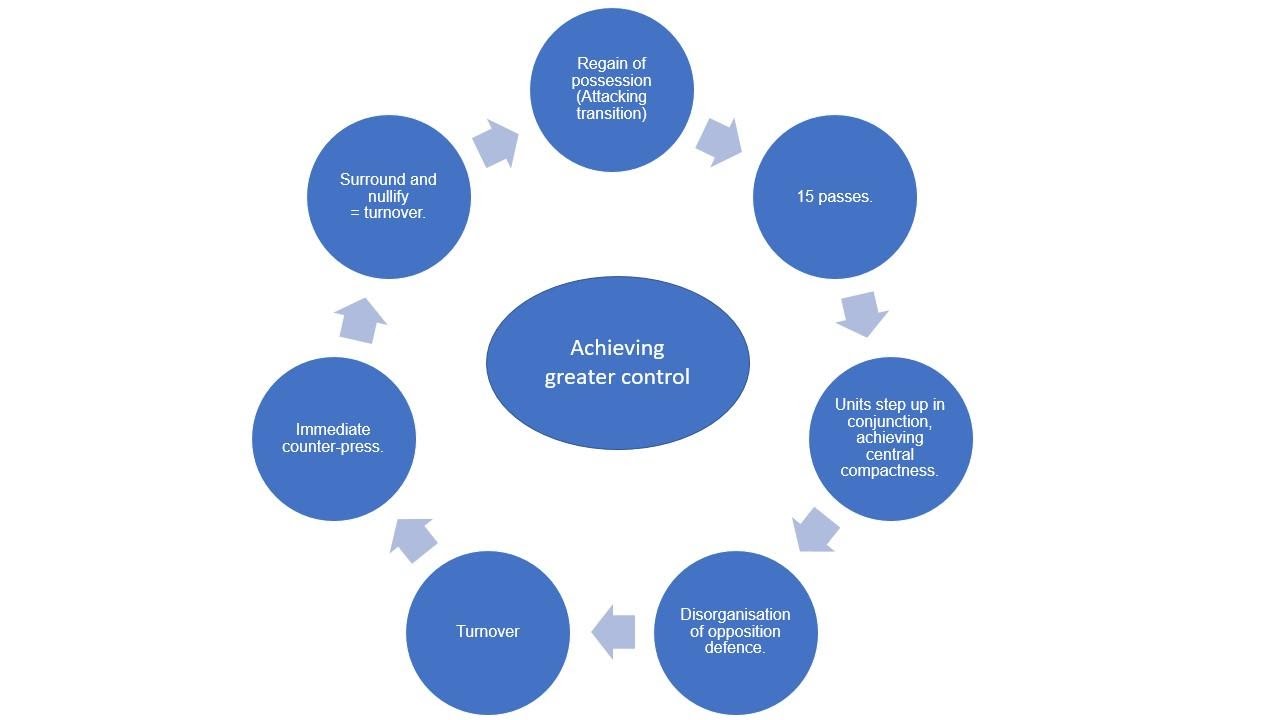

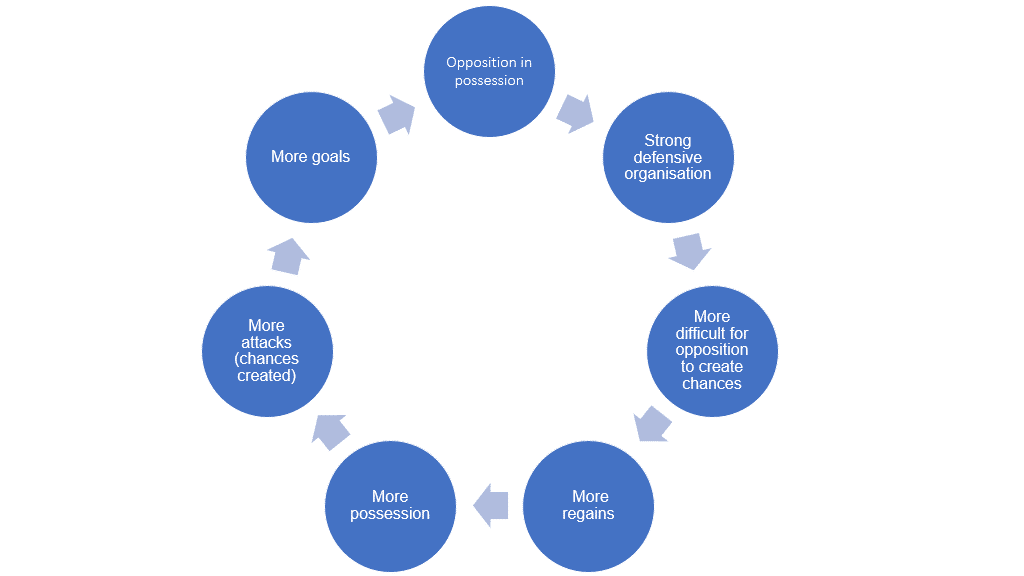

The 15 pass rule seemingly derives from the concept of trying to achieve as much control as possible in football, both in and out of possession, as 15 passes seeks to provide periods of sustained pressure, obtained through short, sharp passing, but also to disorganise the opposition defence and allow the team in possession to step up in unity, which facilitates a more effective defensive transition. Visualising this cycle would perhaps look something like the following:

This further highlights the connection between the elements and also the cyclic nature of the game. This particular cycle is predicated on the idea that more possession results in greater levels of control, predominantly because the defensive team is always in a reactive state (their actions depend on the actions of the team in possession), therefore, the offensive team (in possession) always holds the initiative, which can manifest itself in a level of control.

The amount of passes is more so a guide whereby central compactness can be achieved, however, it can also be achieved through a smaller volume of passes. A sustained period of passing is idyllic because it offers the team the opportunity to move forward in unity and gain territory; the number of passes is just a simple guide rather than the primary objective, in my opinion.

The following example from Napoli’s 4-1 win over Lazio in 2017/18 highlights how a compact centre in possession facilitates a greater counter-press if the ball is lost centrally.

Anticipating the next pass, or the free man as it’s named in Pep Confidential, is another crucial aspect of defensive transition. In essence, anticipating the next pass after the ball is lost allows the now defensive team to apply aggressive pressure onto the player in possession, who should be isolated, if the original defensive team has become disorganised as a consequence of the sustained period of opposition possession.

This defensive principle, i.e., without possession, has a desired outcome which is advantageous from an offensive perspective (high turnover), which further highlights the overlap between these two factors and how they can facilitate greater transitional moments. This manifests Jesse March’s principle: “pressing is attacking without the ball.”

The example below demonstrates the value and importance of anticipating the first pass after possession is lost: Napoli possession is lost mid-way through the Lazio half as Stefan de Vrij tackles José Callejón; he directs the ball towards Sergej Milinković-Savić (the free man) in the process.

Jorginho anticipates this pass/ricochet and applies aggressive pressure. In doing so, he forces the Serbian midfielder into an error and possession is regained. Napoli then keep possession for a sustained period, moving up the pitch as a unit.

In addition to anticipating the first pass after the ball is lost, I also believe anticipating and pressurising the receiver of the following pass is a crucial element of counter-pressing. This is predominantly because I believe it generates a greater volume of turnovers than the first man who receives a pass following a turnover.

If you anticipate the first pass and congest the area, passing options will be limited for the player in possession and therefore it may be easier to predict where the ball is passed next, which has a greater constraining effect because aggressive pressure and a lack of options typically results in either a foul (the ideal scenario for the team in possession at this stage), or a turnover.

It also affords the team without possession more time to crowd the area where the ball has been passed originally, which means if the ball is played short to the next player, pressure will be more immediate and therefore difficult to combat.

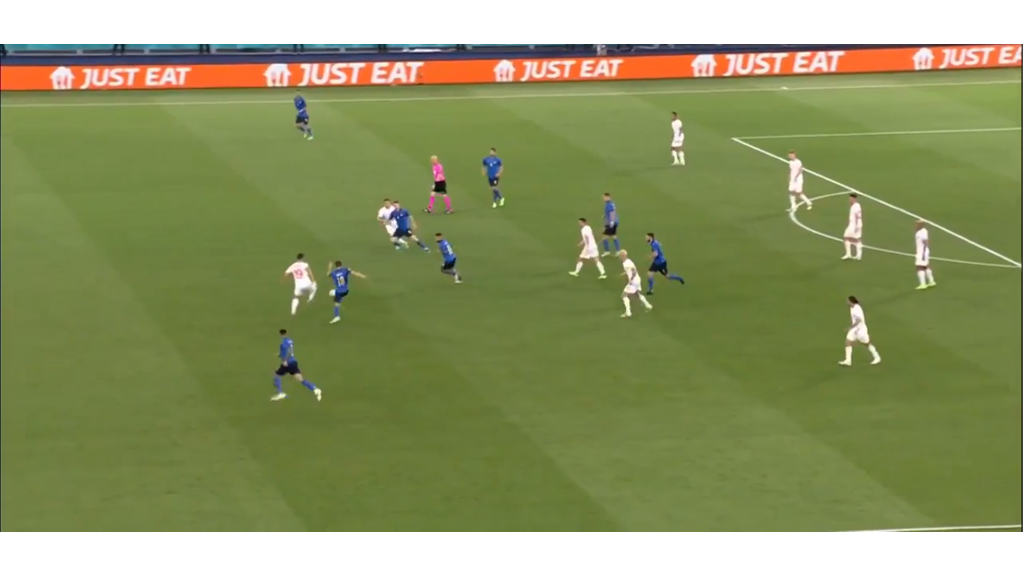

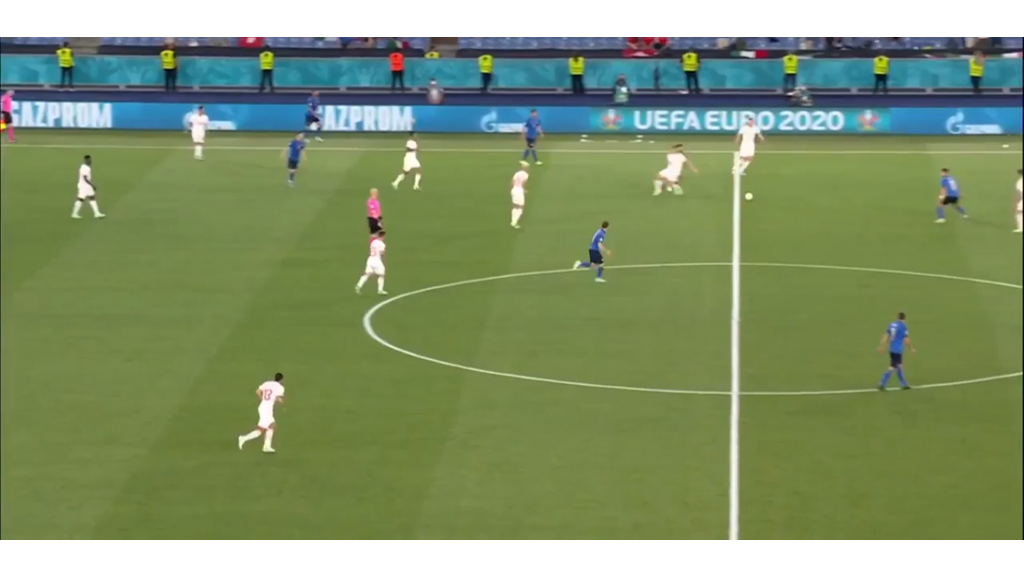

The following example from Italy’s 3-0 victory over Switzerland at Euro 2020 highlights the potential for turnovers when anticipating and pressing the second receiver after the first, following the loss of possession.

Possession is lost after a period of sustained play in Switzerland’s half. Grant Xhaka, who the ball originally breaks towards, plays the first pass into Xherdan Shaqiri, who is immediately pressured by Jorginho (he is excellent at this).

Italy are able to congest the area as a result of their central compactness whilst in possession. Therefore, the only realistic, short passing option for Shaqiri is an inside pass; he must decide quickly due to the aggressive pressure applied by Jorginho – forcing players into quick decisions. Nicolò Barella has already anticipated this pass.

Due to the predictable nature of the second pass, as a consequence of a lack of nearby options for Shaqiri, Barella intercepts the pass before the second player receives possession. Italy turnover possession quickly and are able to restart a period of sustained possession in the Switzerland half.

In order to benefit from the greater constraining effect that occurs when the second pass is about to be played/is played, you must pressure the first receiver and compact the nearby area to limit short passing options, and therefore, to achieve the desired outcome (turnover and regain possession), immediate compaction of the nearby area is critical. Thus, each aspect (anticipating the first and second pass) is equally important; to turnover on the second pass, you must perform step one (anticipate and pressurise the first pass).

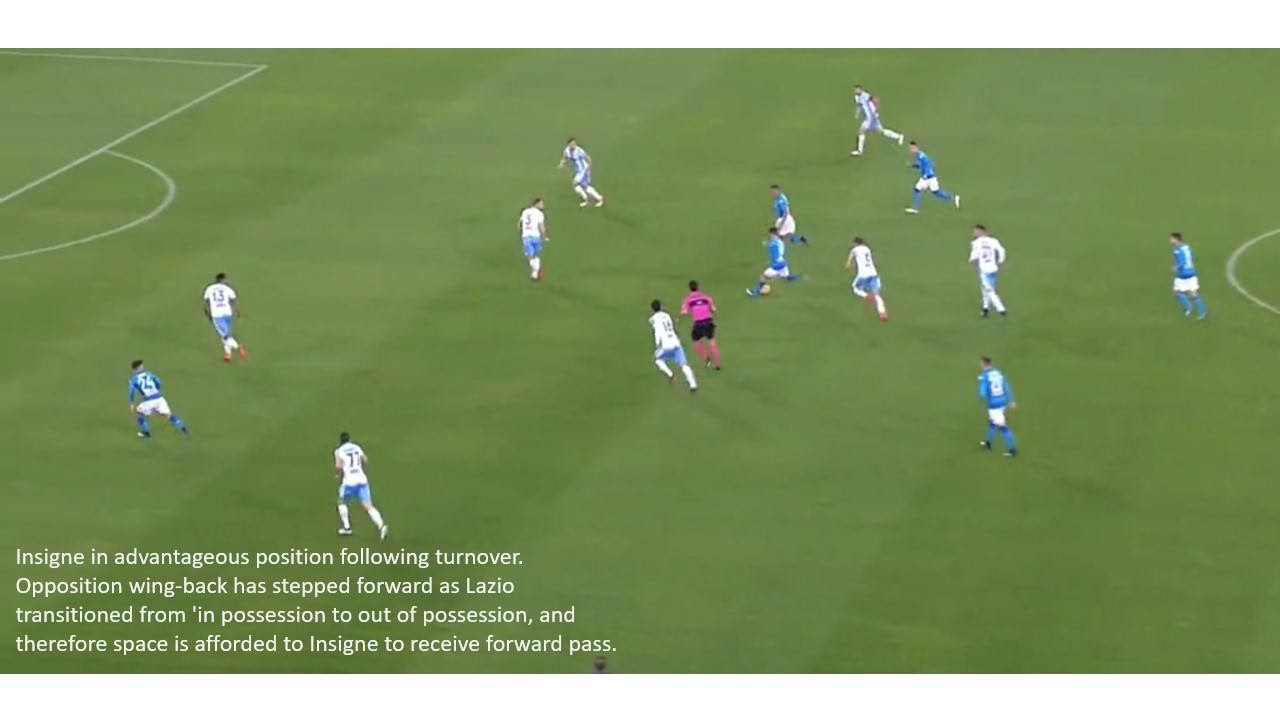

Although the transition after regaining possession from the second pass rather than the first is essentially slower, it is perhaps more advantageous, due to, in my personal opinion, an under-explored aspect of attacking transition. In consolidated attack, the team’s attackers, most prominently wide players (ones who would not be directly involved in a central counter-press) obtain consolidated positions, and therefore when possession is lost they naturally occupy dangerous space in the event of an immediate turnover.

This is augmented by the defensive team who are mid-way through a key transitional moment; transitioning from defence (marking men, tracking runs, protecting space etc) to being a passing option for the player under pressure, which results in a change of position and mentality. Ultimately, the extra 1-2 seconds which derives from regaining from the second pass rather than the first, extends the original transitional period from defence to attack for the team who was originally defending.

As such, when the counter-press achieves its desired outcome (turnover), they are more out of position from a defensive perspective and thus more time and space is afforded to the high and wide attacker who has remained in an advanced position due to their minuscule defensive responsibility in the central counter-press.

In essence, the positional superiority for the attacker is even greater if the ball is regained and played forward following the second pass, rather than the first pass, because it facilitates more time for the opponent to transition to being in possession and therefore more space is granted to the attacker upon reception of the forward pass following the regain of possession as the defender is more out of position. To speak less abstractly and to decipher this idea, here is an example:

In addition to compaction of central areas aiding defensive transition originating from central areas, flank compaction (out wide) in possession also facilitates a greater defensive transition. Flank compactness in possession helps solve solutions out wide during consolidated possession when the opponent attempts to constrain you, however, it also makes it easier to regain possession immediately after losing it if options are nearby.

This is also supplemented from a pressing perspective due to the constraining effect of the touchline and perhaps a less detrimental situation if the opponent manages to play out of the wide counter-press due to the increased distance from goal in wide areas compared to central, thus affording the team out of possession a greater amount of time to recover and defend the situation.

I believe these factors facilitate more aggressive, intense counter-pressing than central pressing due to the decreased exposure to danger. The following example demonstrates the point above: short options when in wide possession = able to constrain and nullify the opposition to a greater extent if possession is lost = more regains.

To conclude this section, it is worth noting that the efficiency of the counter-press can depend on the players’ ability, or the team’s ability as a collective unit (which can be enhanced by the ability of the players) to anticipate the direction of the pass and apply immediate, aggressive pressure onto the opponent. However, this point is not to detract from the importance of positional factors.

The focus of this article will now switch to preparing to attack whilst out of possession. Referring back to the brilliant Pep Confidential, Guardiola explains that he works extremely hard on defensive organisation on the training ground despite his teams (Bayern Munich in this case) typically having greater amounts of possession than the average opposition. This once again highlights the overlap between defending and attacking which is demonstrated in the cycle below.

Although this link is perhaps less significant than defending with possession, I believe it is still worthy of mentioning. I feel the overlap is perhaps less prominent because the defensive transition is potentially more dangerous from a defensive perspective and therefore the setup or structure in possession can drastically impact the transition, whereas the offensive transition is perhaps more so dependent on context and therefore the initiative perhaps lies in the hands of the players.

In essence, in my opinion, it requires less preparation. The idea is that compactness between units out of possession facilitates a more advantageous offensive transition. Perhaps in this case, ‘more advantageous’ is based on personal preference rather than objectivity; however, I do feel it greatly impacts the team’s ability to secure the first pass and therefore possession before progressing up the pitch.

For example, greater commitment to the centre or ball side could allow you to play out of the counter-press when a turnover occurs. However, as explained previously, this can be easier for the opposition to constrain when pressing immediately after losing possession and therefore perhaps compactness alongside vertical/horizontal stretching upon turnover is optimal as it creates a forward passing option (to an outlet) in order to escape pressure and/or the main location of the counter-press.

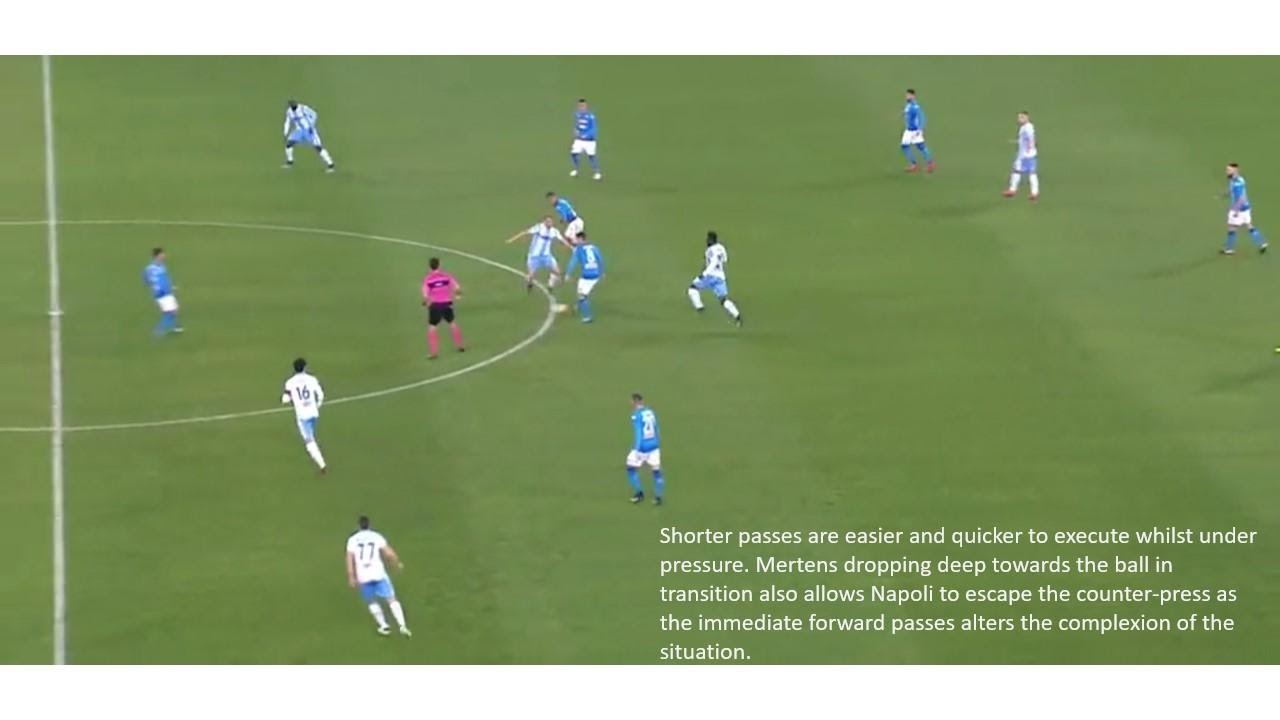

This optimal structure was evident during Maurizio Sarri’s time at Napoli, with Dries Mertens consistently dropping deep from centre-forward upon turnover to support ball possession. The initial reaction was to drop towards the ball rather than move away from it (to exploit space in behind), which demonstrates the importance of securing possession after regaining it in order to sustain it. In my opinion, there were three main reasons behind Mertens dropping deep immediately after winning possession:

- To provide a greater network of short, sharp passing options in order to escape the counter-press of the opposition. Shorter passes are essentially easier to execute than longer passes and completion takes significantly less time, which facilitates quicker ball progression and the ability to move up the pitch as a unit once possession is regained.

2. To provide an immediate forward pass that secured territory and also allowed Napoli to escape the centre of the pitch or the counter-pressing location. This is crucial in avoiding the intense counter-press of the opposition as the immediate forward pass often results in the opposition backtracking and losing further territory which was a result increases the chances of possession being progressed and thus sustained for a longer period of time.

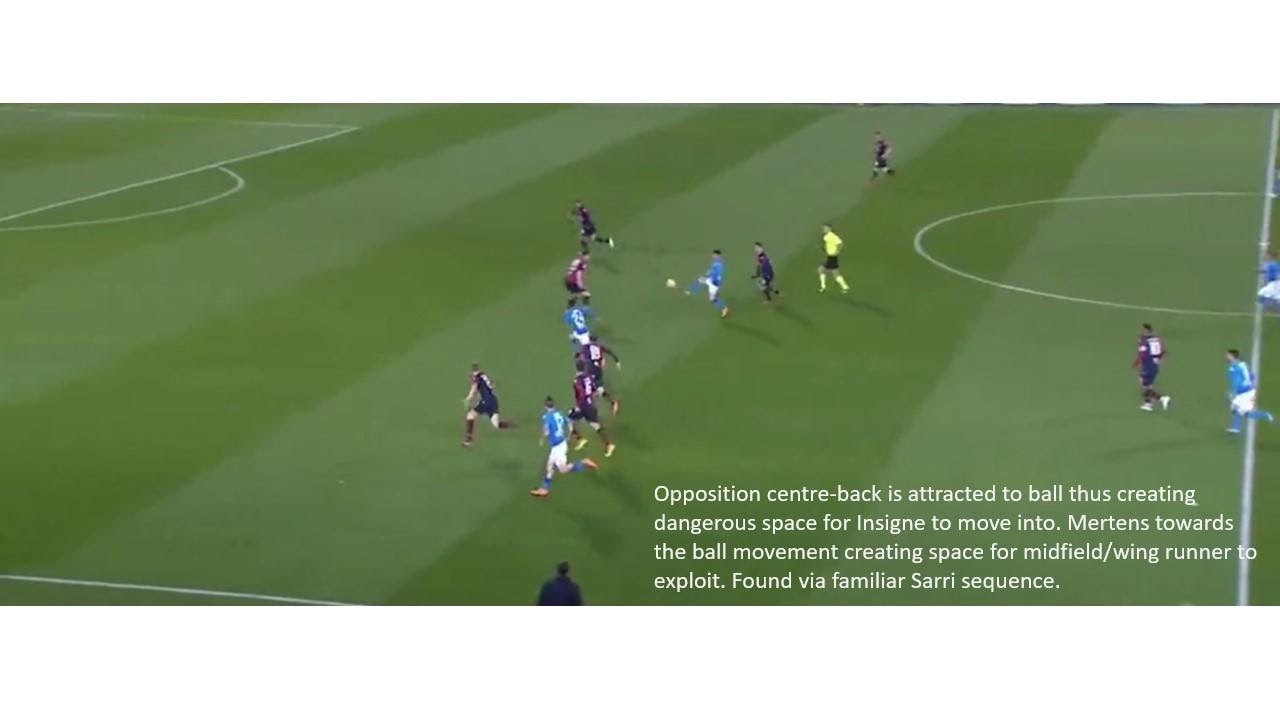

3. Dropping deep provides a platform, or an opportunity, for combinations, particularly the up-back-through sequence which was so prominent under Sarri. Mertens dropping towards the ball to receive inevitably dragged an opposition centre-back forward due to their aggressiveness as they seek to win possession back immediately after conceding it.

However, this often created space for a runner to exploit, which facilitated the back-through sequence. This was most prominently a runner from central midfield or a wide area; a player who was in an advantageous position to do so upon turnover.

Perhaps the following example from Italy’s 3-0 victory over Switzerland at Euro 2020 is the best example of the three reasons above. Jorginho receives first pass following turnover; his immediate reaction is to play forward to Lorenzo Insigne. The Italian midfielder has a few available options, mostly short. The forward pass is the beginning of this ‘up, up, back, through’ sequence.

Immediately upon reception, Insigne flicks the ball around the corner towards Ciro Immobile, the centre-forward who is dropping deep to support possession. Meanwhile, Barella has recognised the space created from the Swiss centre-back following Immobile forward and is beginning his run into the vacated space. The pass from Insigne -> Immobile is the second ‘up’ pass within this sequence.

Immobile passes first time to complete the ‘back’ pass of the sequence, which opens space for Insigne to play the ‘through’ pass to Barella to complete the sequence.

Overall, an advantageous transitional moment is created due to original compactness out of possession which allowed Italy to regain possession and play forward away from the location of the opposition counter-press and to the feet of the dropping centre-forward which facilitated the combination.

In summary and to compare the two main elements discussed in this article, preparing for the defensive transition is a reason for making 15 passes, in order to achieve central compactness by moving forward as a unit, whereas a greater offensive transition as a result of compactness out of possession is more so a consequence of achieving the desired outcome from a defensive perspective when out of possession, rather than the main reason behind it.

It is also important to note that individual quality is more influential in these elements of the game, more so than counter-pressing (starting positions are more important to the success of the counter-press). Players that are able to sustain possession under pressure and pass forward in tight spaces are vital to the original stages of the offensive transition.

In summation, this article has focused on how defence and attack overlap, and how this overlap, if prepared and produced correctly, can create more advantageous transitional moments.

I believe this highlights how football should be coached and analysed wholly rather than in isolation; this approach takes into account the fluid nature of the game and therefore from a coaching perspective, you are more able to recreate game-like situations in training, for example, practices which always contain an element of transition, rather than ones which focus on attacking or defending in complete isolation.

To conclude, I leave you with the Thomas Tuchel quote once more, as it perfectly manifests the reasoning behind this approach, and this article, for that matter: “We spend very few minutes and moments in training isolated on defence or attack. We train in complex situations because the game is complex and we don’t try to divide the situations in an artificial way.”

By: Ollie Himsworth / @ollie_himsworth

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Carl Recine – AFP / Marco Rosi – SS Lazio – Getty Images