Vicissitudes of Verticality: Lazio

Stretching the opposition vertically is typically conceptualised positively because it increases the space in between the opposition’s lines, granting additional space for the players in possession to move into to be effective at eventually infiltrating in behind and generating a goalscoring opportunity.

However, the flipside of this is the potential for opposition benefit from the spatial circumstances produced, with errors or risky passes which lead to turnovers now being especially dangerous because of the lack of compactness out of possession, allowing the opposition to exploit the attacking shape through a counterattack.

In essence, while large distances between players in possession can be positive for stretching the opposition defence, it can often lack a counter, counter, whilst additionally fostering a potentially more high-risk playstyle more conducive to turnovers because of the lack of short, safe passing connections for potential progression to provide a support structure for the player receiving in space. To analyse this paradigm, this article will investigate Simone Inzaghi’s Lazio.

In short, Lazio deliberately add backwards depth which creates a conundrum as to whether to continue pushing higher onto Lazio’s deepening line or to allow them to consolidate possession in deeper regions. In this regard, they seek to bait a press in part because that creates a conundrum for the defensive line should the opposition decide to press higher: stay deeper to protect space in behind which a probing Ciro Immobile could potentially exploit.

Immobile could cause them issues through the additional time generally afforded to defenders because of the general state of numerical superiority encountered by teams building out of defence through depth, making them more resistant to pressure thus more capable of exposing compactness through time and space. Or otherwise, push forward to maintain vertical compactness to reduce the possibility of Lazio playing through the lines of defence through varied vertical build-up which could grant them the positional superiority.

The situation is more complex than the binary push up or maintain similar level of depth but can rather be conceptualised across a continuum; and the severity of the consequences generally vary across this continuum for both sides. I.e., pushing extremely high and maintaining compactness via a high line exposes a greater degree of space in behind but additionally increases the chances of a turnover being generated in high areas and the effective space of Lazio’s players nullified which makes exposing the compactness difficult.

Effectiveness of execution of particular consequences is difficult to anticipate in the abstract because of the fluctuations which are present both internally for all teams and externally with regards to opponent faced; however, predictable, if broad outcomes can be ascertained through looking into the potentialities of either sides effective/ineffective execution.

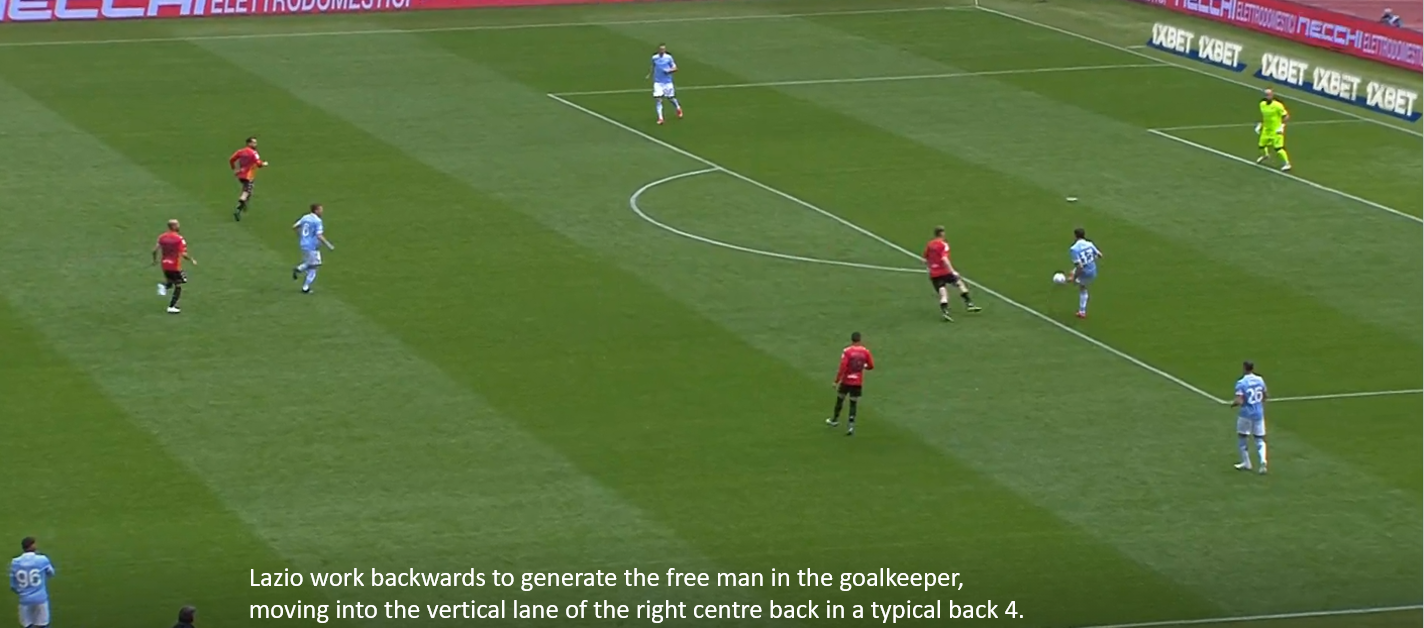

Tools which increase Lazio’s effective execution include the creation of a ‘flat’ (goalkeeper is frequently deeper but the term helps elucidate the horizontal space occupation which is reminiscent of a back 4 as the centre backs, two of whom are now deep full backs are on the same horizontal line as the centre, centre back) back 4 through involving goalkeeper Pepe Reina in possession, something which is only achieved without extraordinary risk in deep areas of the pitch.

The achievement of a ‘flat’ back 4 provides Lazio with full horizontal coverage on the first line which in turn either increases time on the ball for the recipient or reduces the opponent’s horizontal compactness/coverage increasing opportunities for vertical passing in between the lines or the danger of switches. The ‘deep full back’ can be an irritating position to press because it maximally stretches the opponent vertically and draws them into wider areas reducing central coverage or compactness depending on decisions made.

Typically, the touchline can be considered to have a constraining effect, meaning the players in possession can be more easily isolated from passing options. However, the potential for additional depth is present through goalkeeper involvement.

Usually, the goalkeeper is uncovered in a marking scheme which should result in him being free or otherwise a free man appears elsewhere due to how player resources are allocated – the goalkeeper is always a +1 and moving as there is an additional layer of backwards depth to provide support, conditions of isolation should not have been reached.

The pass to the goalkeeper subsequently permits a switch of play to the opposite flank or shorter to the centre back with an established connection to the underloaded flank allowing for the generation of a potential transitional moment or at the very least alleviates opposition pressure.

This is just one of many potential sequences resulting from the flat back 4 approaches as the permutations of reduced horizontal and vertical compactness, potentially majorly if pressing the goalkeeper providing additional support and short passing option, as it opens space for a lateral pass into the centre or potentially an up-back-up sequence from full back to goalkeeper to defensive midfielder who can consequently switch.

The possibilities therefore are wide in scope; however, the outcome provided execution is solid: a vertically stretched opponent and a possible transitional moment if the opponent has reached the stage where they are advanced against the goalkeeper. To better elucidate the concept, here is a practical demonstration:

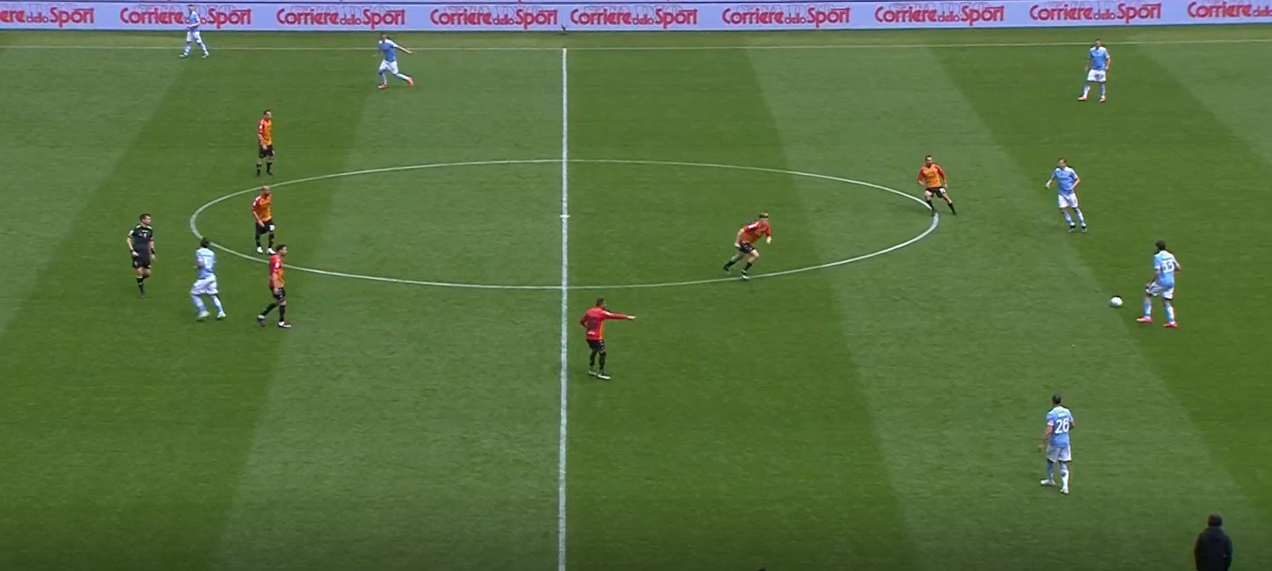

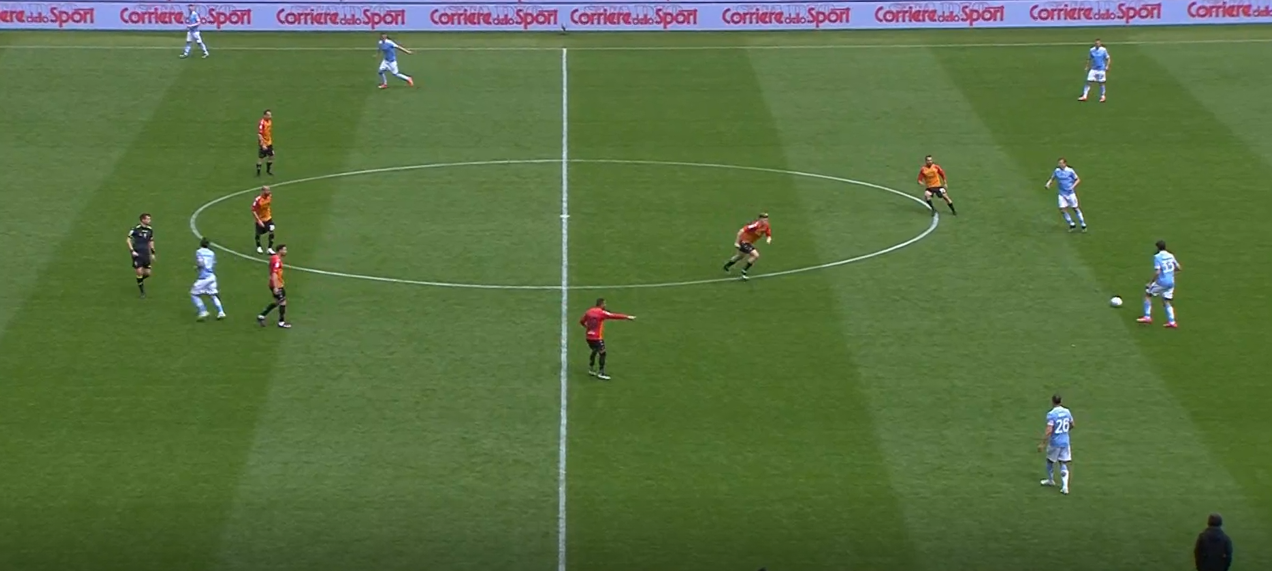

Reina occupies the vertical position associated with the right centre back in a 4. Ștefan Radu, as the ball progressed backwards down the left it was already placed accordingly, whilst Adam Marušić dropped deeper and wider in accordance with the positional requirements.

The ball is moved to Manuel Lazzari who has a triangle of options available. He passes backwards to Marušić, who works the angle back to Reina who is free and presented with this situation.

Luis Alberto now has an easy pass to the underloaded flank, provoking a potential transition and assuredly bypassing the press.

This sequence, along with the conceptual framework hopefully clarifies the utility of the flat back 4 in permitting transitional moments through vertically and horizontally stretching the opposition – the goalkeeper is a free man in an active position, his wider positioning undermines any touchline containment attempted by the opposition through adding a difficult to cut passing option and pertinently, if pressed, opening another player open in a more advanced region.

The additional man makes overloading the ball side easier, while the consistent safe passing connection due to the difficulty in cutting the depth after circulation makes the up-back and switch (and whatever permutations evolve due to the nature of the opponents pressing) possible.

This concept in practice can be seen in more advanced regions of the pitch additionally with Lucas Leiva dropping in rather than Reina advancing, hoping to similarly draw a marker forward which seeks to vacate space, leaving it unpatrolled for potential interceptions facilitating verticality through decreasing the coverage of the opposition space in between the lines.

The positioning of the deep full-back moreover allows the wingback to push higher which increases the extent of vertical stretching with regards to advancement as he is no longer required to provide a shorter passing option in wide regions during the build-up. This means there is a compounding impact resonating from the deep full back positioning of the centre back facilitated through the back 4 structure in that they stretch the opposition’s first line, while the oppositions last line is being stretched by the wingback.

This moreover generates additional horizontal space through increasing the defensive horizontal coverage required, therefore reducing compactness as the wingbacks pose a direct threat in behind, accessible through the deep full-back, who is generally free upon receiving possession with time and space because the opponents initially prioritise central compactness to prevent central infiltration.

This has a pinning effect, keeping the opponent’s wide defender deeper, thus increasing the space for central infiltration through reducing 2nd line coverage while also facilitating positional manipulation as the wingback becomes more important as a spatial rather than direct possession actor.

Horizontal space can moreover be used for indirect central infiltration, particularly if the line in question is vertically stretched because it allows the wide player to penetrate inwards, going around the block rather than through it to achieve central space in between the lines which is larger due to the vertical stretching. This means there is at least a partial symbiotic relationship between the two, as vertical stretching increases the efficacy of horizontal stretching through greater permitting the ‘around’ rather than through option.

However, when facing a higher zonal press in particular, which seeks to show Lazio into wide areas to constrain, the wingback becomes an important passing option. This is because of the threat they pose in behind, meaning their opposing marker will want to stay behind them, typically with space to gain the make up for the initiative granted to the runner.

As such, that when the wingback drop deeps to support, they have initiative and additional time and space which can aid in finding runners into the space in between the first and second lines which is generally large and underoccupied. This aspect was highlighted in this sequence against Napoli:

The deep flat back four vertically stretches Napoli, drawing them forward. Moving the ball central to wide allows Marušić to be the free man as Lorenzo Insigne must cut the passing lane to Manuel Lazzari before engaging. The ball being in wide areas triggers Napoli’s man-orientation as they seek to reduce the size of the available playing pitch, attempting to compound the effects of the touchline and backwards reception with regards to compaction.

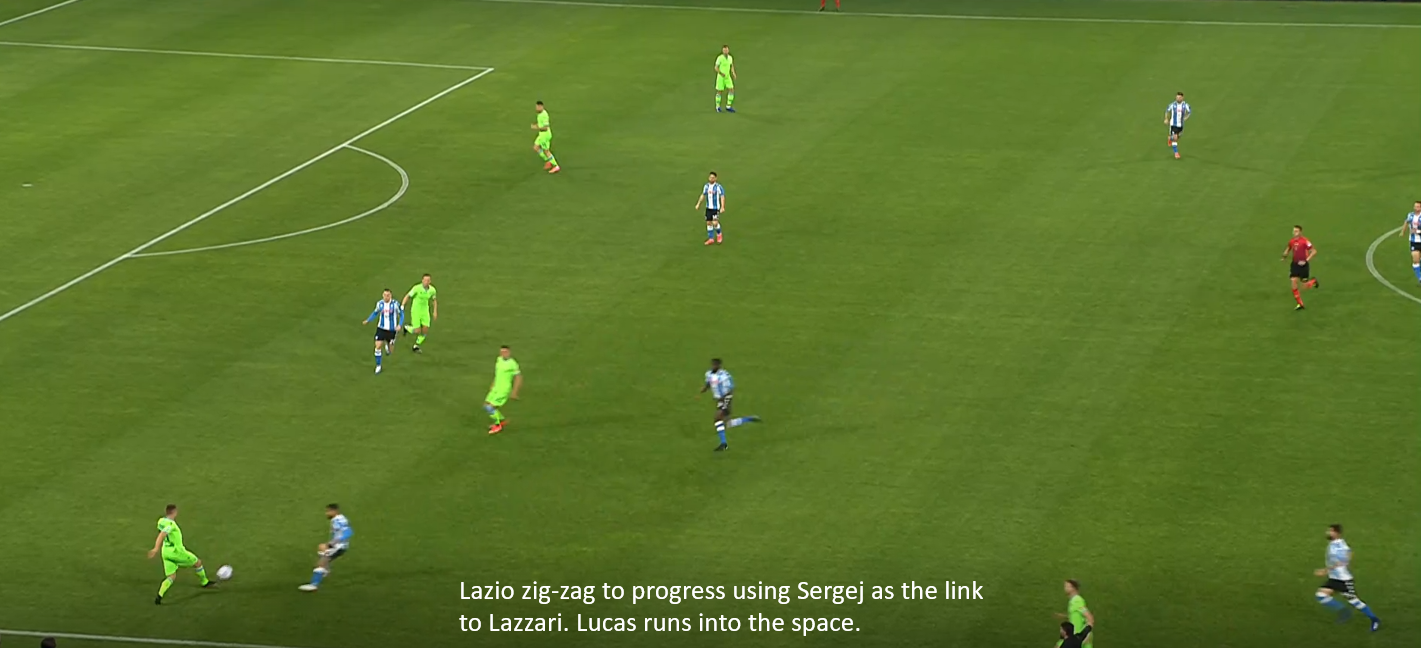

Tiémoué Bakayoko’s man-orientation to Sergej Milinković-Savić vacates the ball-side space in between the 1st and 2nd lines. Therefore, this pressure only works if that space is rendered ineffective to justify the compactness. Otherwise, the compactness will be exposed due to lack of space coverage. This is what happens to Napoli in this sequence.

Lazio can progress despite the pressure, because many of the movements are automatised, meaning they are aware of what the subsequent action will be because it is a common occurrence drilled in training.

This is an additional benefit to building backwards to consolidate possession as it produces predictable game states where increased knowledge of subsequent actions can be harnessed to increase effective time, a jargonistic way to describe the reduced importance of time as assessing options is not required (to the same extent) due to prior knowledge of anticipatable positioning.

This can be particularly useful when attempting to contract the opponent to then expand into the space left vacant such as in this sequence. Sergej knows to drop deeper to vertically stretch the opposition, which allows Lucas to then move into the space with the passing angle opening via Sergej to Lazzari.

Napoli are attempting to reduce the size of the effective pitch through compact pressing, and Lazio aware of this are contracting, because it creates space when bypassed. Lazio are seeking Lucas here, who is on Piotr Zieliński’s blind-side; however, because of the initiative of the attacker in space, it is likely he would have received the ball regardless, albeit under more pressure.

For transparency, in this sequence, execution was not perfect, largely due to the pass by Sergej which required Lazzari to receive at an awkward body angle meaning the pass to Lucas was not open, where he hastily laid it off for Sergej, but played it out of play.

This, however, does serve to highlight an element that turnovers in these compact situations for both sides typically are not microcosmically dangerous because the ball often goes out of player or otherwise a battle for second balls/recoveries begin, or the team that has regained possession plays it backwards to consolidate consequently allowing the opponent to reform into their defensive shape.

Lazio’s primary issues defensively lie in their losing of possession once committed to the transition because the large spaces which catalyse such promising attacking events are also promising to the opponent when the turnover occurs; hence, the vicissitudes of verticality. I think the sequence leading to Bayern München’s 3rd goal at the Stadio Olimpico highlights this exactly.

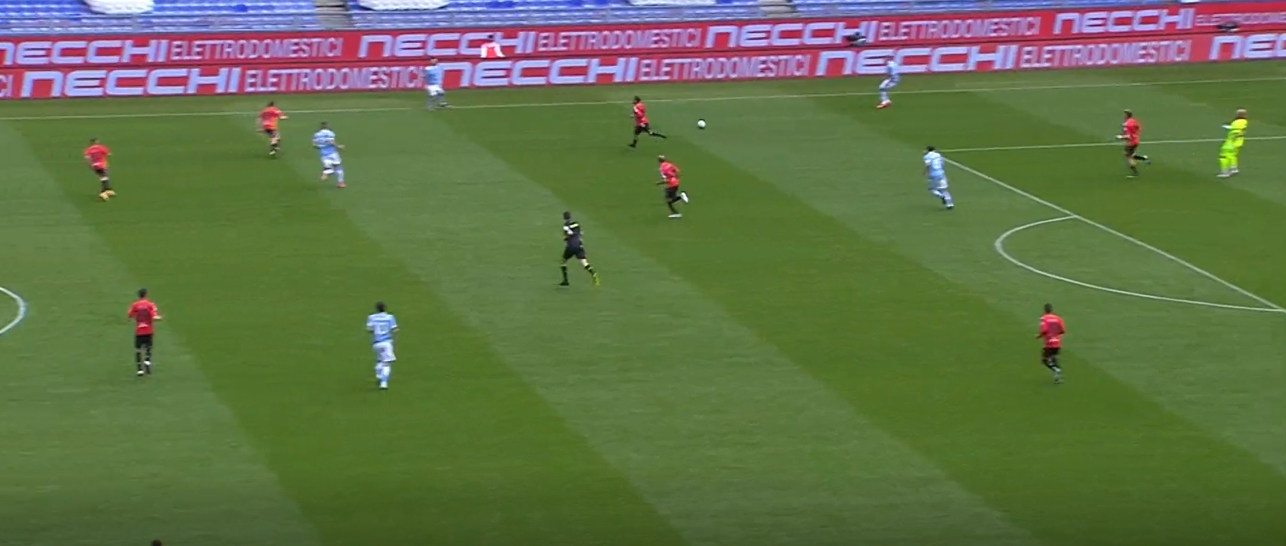

Reina holds the ball deep while Luis Alberto drops deep to support, making an alternative run to drag Leon Goretzka deeper, thus reducing Bayern’s compactness through increasing the gaps in between the 2nd and 3rd lines.

This created space for Joaquín Correa to drop into, enough space where technical inaccuracy was not particularly pertinent because of the lack of challenges for second balls as Bayern lacked the support structure to compete meaning aiming it in approximately the right direction of a teammate was sufficient, facilitating the raised pass. That is not to suggest technical accuracy is not desirable, but rather not necessary.

The scrap for second balls benefits Lazio as they can better compete due to dropping attackers while the run of Lazzari prevents Bayern’s defending in the initial duel because of the potential for an up-back and through manoeuvre.

The potential for that manoeuvre was facilitated itself through the initial vertical stretching through providing the Lazio players the space and forward momentum (therefore, under no direct forward pressure which could cut progressive passing lanes) to move into to receive backwards passes with potential for instant progression. Thus, the combination of the elements: initial vertical stretching through heavy support network to goalkeeper in possession; space in between the lines for dropping forward and second ball contestation.

Lazzari’s vertical stretching to pin Bayern’s back-line and the completion of the circle as that threat is made effective by the potential for a backwards pass into space where progressive passing options cannot be cut due to forced high commitment from Lazio (forced insofar as Bayern pressed man-oriented from goal-kicks and thus left themselves susceptible to positional manipulation).

This game state continues due to the continued requirement for the dropping of Bayern’s backline to respond to threats in behind forced a holistic retreat in an attempt to salvage a degree of compactness. The distance between the lines and transitional game state of retreat creates a myriad of potential passing options which ends in a cross from the underloaded side in the picture.

However, the loss of possession catches Lazio in a transitional state, with as pictured a great deal of numerical commitment. The situation is now inversed and the constant introduction of newly created effective space is flipped onto Lazio as the defending team, and Bayern as the attackers.

For Bayern, the response was dropping backwards to cover more crucial areas potentially being infiltrated by vertically stretching players while providing sufficient time for compactness horizontally between the first line and in between the 1st and 2nd lines vertically to be established.

For Lazio, it was to provide passing options to the ball carrier or to stretch the pitch to potentially receive possession and achieve good spatial occupation. In essence creating a good spatial situation in possession. The turnover reverses this and now they need to cover defensively but have exhausted themselves pushing forward and lack the momentum going in that direction, further benefitting Bayern.

They dealt poorly with the second ball and whilst probably having enough men back to typically index against counters were caught by an intense Bayern on the break who could use all the space in between the lines manufactured by Lazio to their own benefit and reverse the situation of transition.

The defenders lacked the numerical support to adequately cover all vital spaces, while good individual play from Kingsley Coman was able to exploit the increased space to engage in more isolated defender scenarios in addition to the threat of such and losing forced positioning which allowed progression. Another example highlighting potential pitfalls occurred against Sassuolo:

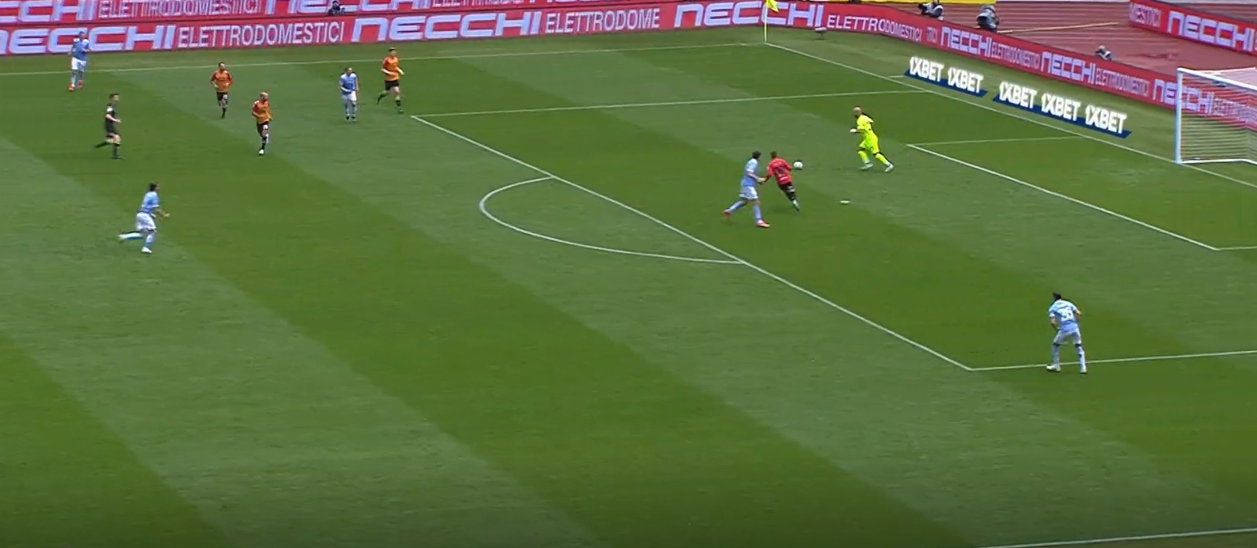

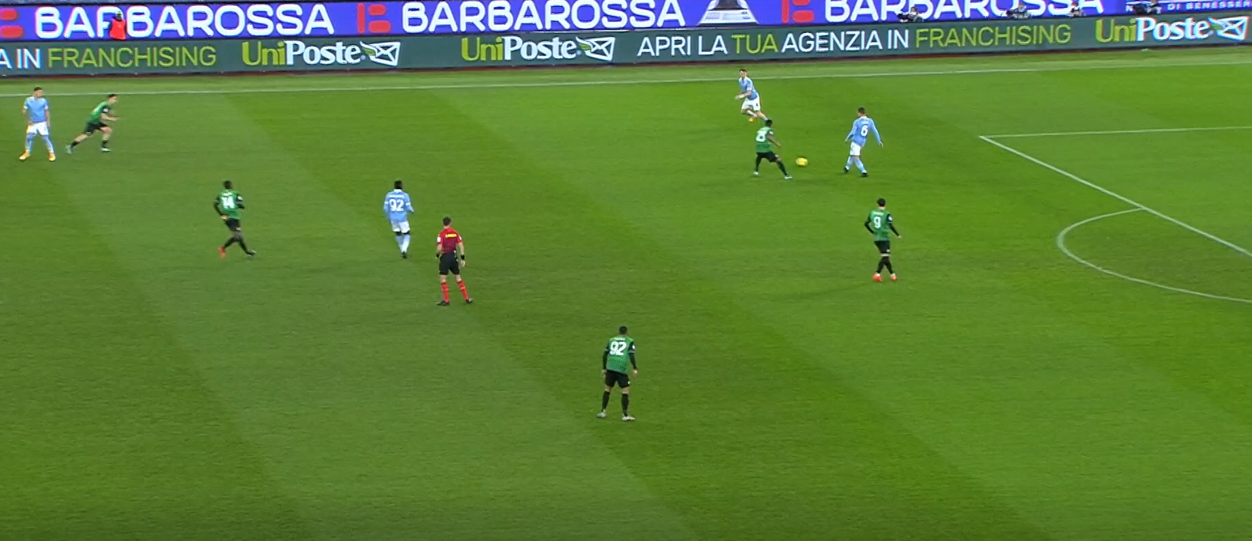

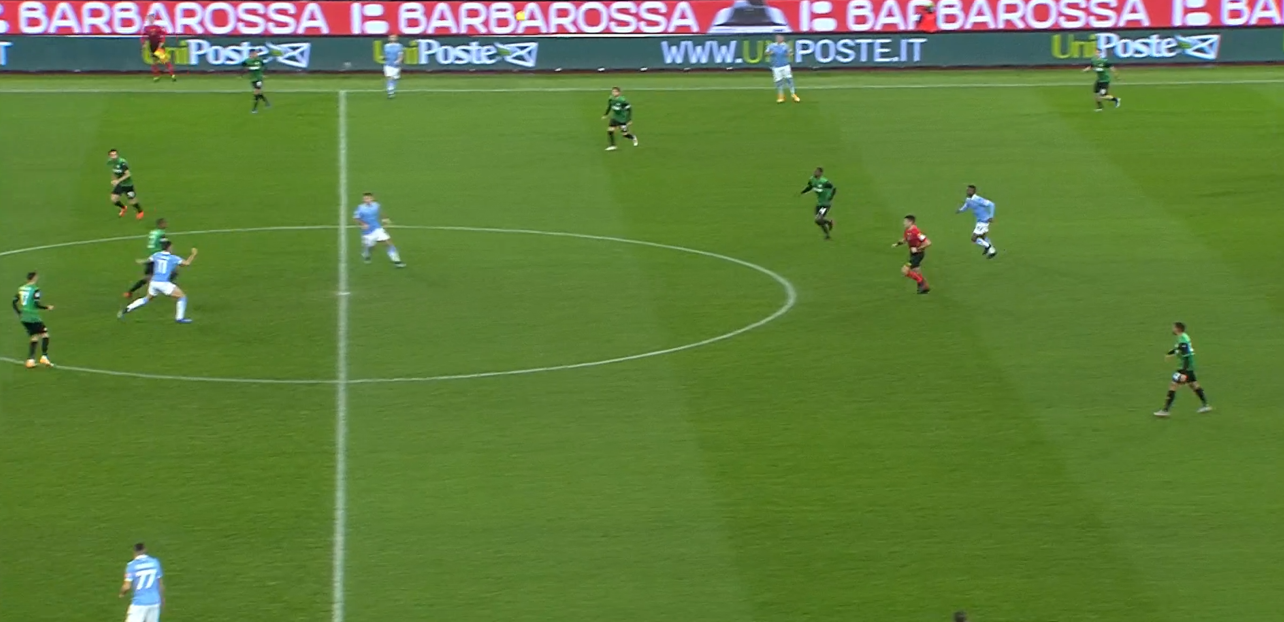

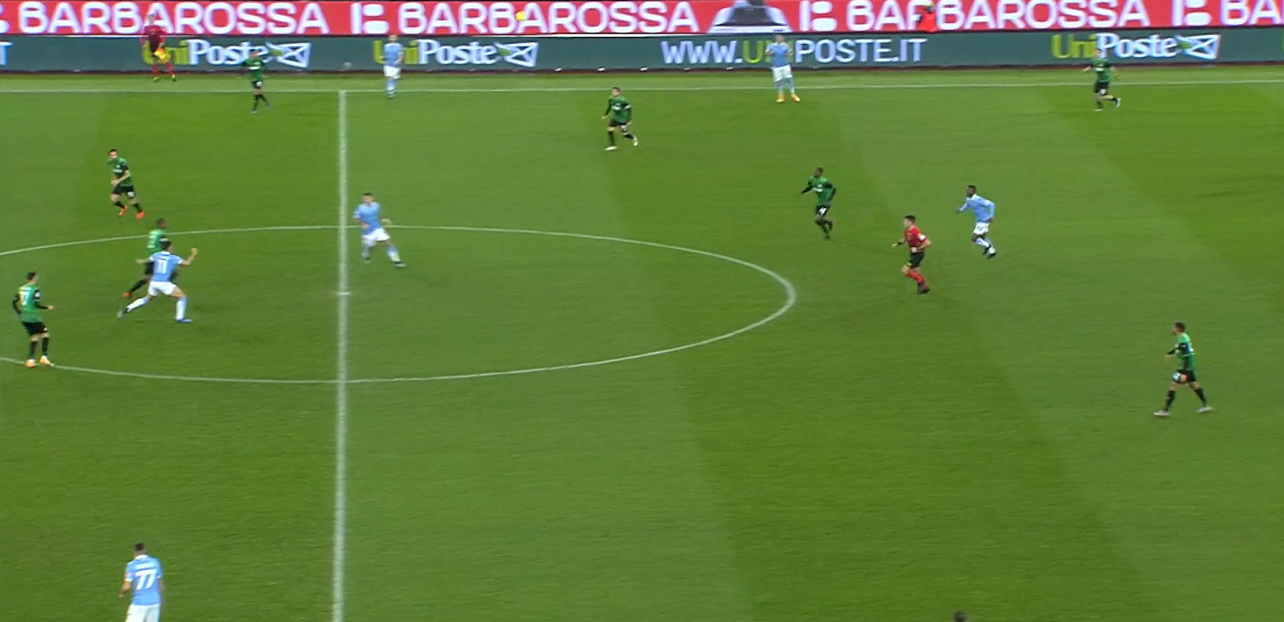

Lucas drops to create a flat back 4, creating the 4-2-4 build-up structure often used by Lazio. Passes it to the deep full back. A lofted ball is played towards the forwards.

Firstly, it is at least possible to imagine an alternate reality where I am highlighting the positives of such vertical stretching should Joaquín Correa win his duel with Marlon, as Immobile has dropped off to receive potential second balls – potentially resultant from a chest lay-off in the perfect hypothetical while because Mert Müldür has compacted granting space for a through pass to Marušić.

However, Marlon wins the duel, finding Manuel Locatelli in space as Sergej Milinković-Savić in the possession sequence moved wide to provide a passing connection should he not be tracked in addition to vacating the half-space should he have been tracked to reduce second line coverage. This results in all three of Lazio’s right-sided players being in the wide vertical corridor after the turnover, thus meaning they now lack midfield coverage.

The flat back 4 with high wingbacks is now exposed as positional recovery from high areas is difficult while Sassuolo are able to first transition centrally because of the wide positioning, then to go wider once Lazio’s defensive compaction occurs as they prioritise crucial areas. A defensive state of retreat is provoked, which is characterised by backwards movement as defenders must continually adjust to newly introduced space which makes it susceptible to cutbacks, such as that scored by Francesco Caputo as the forward has the initiative over the reactive defender.

Juan Manuel Lillo, is quoted with the statement “The quicker the ball goes forward, the quicker it comes back“. This encapsulates the potential issues with transition-based football being discussed and sought to be achieved by Inzaghi.

Fundamentally, once the transition occurs there is a lack of control because players are having to constantly react to newly introduced space in addition to the speed of play in possession resulting in gaps appearing because of the necessary differences in intensity for the players in possession in particular, as because of the potential for a turnover it would be irresponsible for defenders with no ambition of receiving possession to charge forward at a similar pace to the key transitional actors such as the ball-sided wingback or centre forwards.

By trying to infiltrate space the players in possession are creating more of it and subsequently reducing their own compactness as discussed. This is the reason viewing counterattacks and possession-based transitions as separate entities is fallacious, as the underlying factors are the constant introduction of new space and the attack of and or in behind the opponent’s last line at pace which are present in both. There is no real difference in-game state to the one Lazio created via possession and the one created through Bayern’s turnover.

This potentially highlights a flaw in the broad application of the 15-pass rule as it only applies in particular circumstances and under the wider context of positional play where transitions are primarily sought to be provoked in the final third. The 15-pass rule can be pertinent in attempting to gain control and form a consolidated game-state deep in the opposition’s half, where the opponent’s defence is pinned back and compact meaning, they are less of a threat from counter-attacking situations.

The Consigli-Boga: Analysing Goalkeeper Possession against Mid-to-High Passive Blocks

15 passes, however, is not a requisite for good transitional shape, as demonstrated by Lazio, who often use passing to create these transitional game states. The principle from positional play to apply in this regard is the quicker the ball goes up, the quicker it comes back rather as it prevents an over-emphasis on the direct on-ball benefits of transitional state.

The use of press-baiting as a means of space (and thereby) creation necessitates the quick movement of possession up the pitch in addition to wide gaps between players being created. Deeper play stretches the pitch and often requires more dynamic movement accordingly compared to controlled, consolidated states.

That is not to say a dogmatic prism of positional play is the optimal way to play football irrespective of circumstance, rather it can contain useful bits of knowledge elsewhere when selectively applied, and moreover can be misleading when selectively applied as in this instance, the 15-pass rule only works when playing acting out the axiom of the quicker the ball goes up, the quicker it comes back.

Nevertheless, if Lazio abided by that principle rigidly, it would also neuter the most effective part of their game; a playstyle which has earned Simone Inzaghi a move to Champions of Italy, Inter. The vicissitudes of verticality entail a series of trade-offs, predominately due to the potential produced via space created to be reversed onto the team in possession and this is an important to bear in mind.

Personal bias included, I think press-baiting and space creation through deep possession, particularly through using the goalkeeper as an additional possession actor is an excellent way to create chances through disrupting opposition consolidated defensive shape and due to the numerical superiority often providing control in those deeper regions can be used to provoke a series of automatisms which hopefully nullify issues with lack of control during the transition for the in possession team, generating a degree of safety until the last line is beaten.

However, this preference exists in spite of knowledge of the vicissitudes, because I have come to the judgment the positives outweigh the negatives in the long-run. With a higher calibre of players, capable of better defending space at his disposal at Inter, such as Marcelo Brozović, Nicolò Barella, Milan Škriniar etc., I anticipate will be able to produce more refined, higher quality version of his football displayed at Lazio as Inter can realistically seek to retain the Scudetto and improve upon two poor (results-oriented) Champions League campaigns.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Mondadori Portfolio