Echoes of the Fall – Is Jürgen Klopp’s Final Dortmund Season Happening All Over Again at Liverpool?

“History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes” – Mark Twain.

When Liverpool were in the process of hiring their 21st-century idol; the man who, like so few others in the club’s history, could guide them to a raucous, unrelenting state of football revelry, there was a remark made by Ian Graham, Liverpool’s contemporary Director of Research.

He was, with the hope of convincing Jurgen Klopp of its merits, using data to analyse Dortmund’s 2-0 loss to Mainz in Klopp’s final season, one of those results that truly stuck in Klopp’s craw as his side fell to eighteenth place in the table – that’s stone, dead, bottom in the Bundesliga – only fifteen months after being in the Champions League final.

According to the New York Times, Klopp is said to have marvelled at Graham’s description of the game: that Dortmund were killing Mainz, that it was incredulous and astounding for Dortmund to lose it 2-0. Dortmund, to quote the New York Times piece, lost that game “because of two fluky errors.”

So Klopp, validated in his approach and with a few analytical revolutionaries along to properly ensure his side were on the right track, took the Liverpool job, and turned them into, at one point, the world’s best football team.

His heights reached with Liverpool have reached well beyond that Dortmund team – and, despite having significantly more resources, those resources pale in comparison to the state-run competition much in the way that Dortmund’s paled in comparison to the Bundesliga juggernaut they conquered. But, at Dortmund, the cycle ended, and things fell apart. The question is, how similar are the failings of Klopp’s Dortmund to the cracks appearing in this Liverpool team?

An Unfulfilling Window

Klopp’s final transfer window at the helm of Borussia Dortmund (in which, it should be noted, Michael Zorc was in control of transfers, as was the norm), saw Robert Lewandowski depart for Bayern Munich, and Ciro Immobile brought in as his replacement. It saw the return of an old stalwart in Shinji Kagawa, the signing of a brilliant young midfielder named Julian Weigl, the young centre back Matthias Ginter, and the midfield signing of Kevin Kampl.

There was an emphasis on the rise of Pierre-Emerick Aubamayang, who they’d signed the previous summer, and a collective belief in the priority of Klopp’s system over any one player (remember, Mario Götze had trodden the path to Bavaria the season prior on a free transfer.)

There were, however, two notable red flags being waved even before the season began. Ilkay Gundogan had only just returned from a 428-day back injury and needed to be eased into the side, and Marco Reus had, in the second half of the 13/14 season, missed six games with four different muscular injuries. Reus would go on to miss almost half the season with ankle injuries.

These red flags were seen as mitigating circumstances that could be managed: especially if Ciro Immobile could fill the goals void left by Dortmund’s key man. Spoiler: he couldn’t.

Liverpool have a different problem; in that they haven’t really played with a striker in Klopp’s tenure. Roberto Firmino morphed into a more mobile striker, rather than a dogmatic and pure false nine, but he still spends less time in the box than outside it. Darwin Nunez’s much-vaunted arrival may have hit a headbutt-inspired roadblock, but there’s nothing to suggest he won’t score plenty if the system is right.

Lazy analysis would pin it on the absence of Sadio Mane – which discounts how influential Luis Diaz has been so far this season. But, given the lack of midfield depth, a cost of losing out to Real Madrid on Aurelian Tchouameni and having their genuine midfield target (who is, funnily enough, currently playing for Borussia Dortmund) unavailable for purchase yet, the system itself might be the problem. That, indeed, is where the parallels come strongest.

An xG Aberration and a System Malfunction

Liverpool have won every Premier League game on expected goals this season (according to the xG Philosophy’s model, which had them over Everton by a slim 0.07 xG.)

Dortmund’s biggest problem in 2014/15 was not that they failed to get the ball into the box. It’s that they failed to score. When Dortmund had four points on the board – in the relegation zone – after a miserly start, they simultaneously had an xG differential of +8 – that is, they expected to have a goal difference somewhere in the top four. The ball simply wasn’t going in.

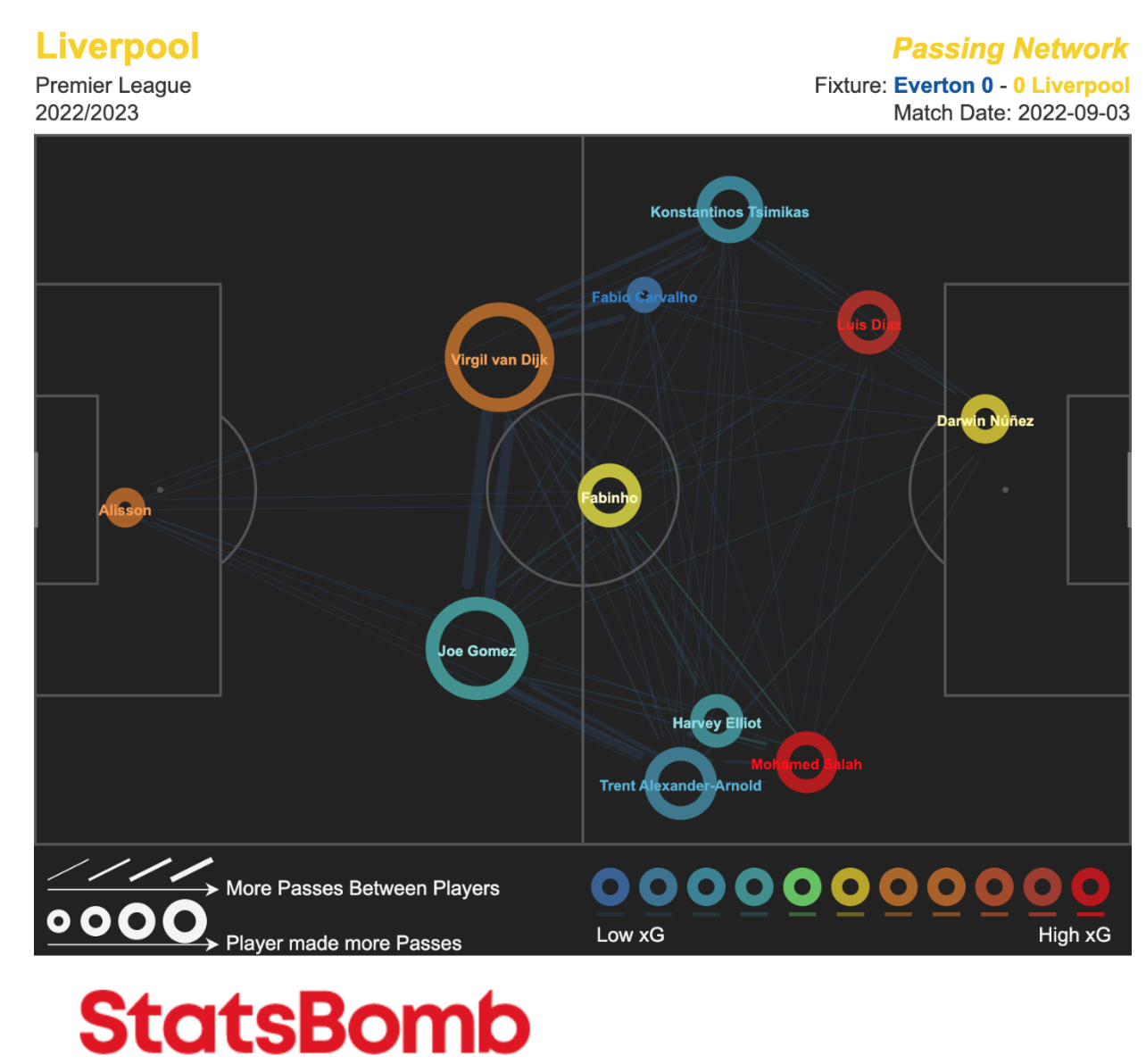

Liverpool currently have the player who’s created the most chances in the Premier League this season: Mohamed Salah, even with his puzzling tactical width. Yet, outside of Bournemouth, none of the goals they’re scoring are traditional Liverpool-under-Klopp goals. It seems like the system itself is faltering under the pressure of its own flaws. Below is the passing map from the Merseyside derby stalemate, courtesy of StatsBomb.

The most notable – and ominous – part of that map is the complete vacuum in front of Fabinho. Klopp’s new system, innovated and executed tremendously last season, counteracted the marking done on Salah by having a three-man overload on the right-hand side – like is present in that passing map – to ensure two things: Salah’s creativity towards the byline, and Trent Alexander-Arnold being able to cross the ball into dangerous areas. The balance of the team, though, effectively swung right, which meant the midfield two became something of a pivot.

Usually, that was Fabinho and Thiago – which worked, because Thiago could spray the passes, and Fabinho could break up the play. The unfortunate plummeting of Jordan Henderson’s form, the injury-plagued Naby Keita, and the stark age gap between Fabio Carvahlo and James Milner means that when Thiago is injured (as he tends to be) Liverpool have a vast vacuum in midfield.

Dortmund, interestingly, had a similar system malfunction. At Dortmund, Klopp stuck to a 4-2-3-1 that got the best out of his intense gegenpressing mantra. He coined a phrase (which he now regrets) of the gegenpress being the best playmaker, and while that is slightly tenuous and reductive to mention, the point is that the press stopped. It just stopped.

A pressing system requires two things: the use of possession when the players are tired, and the synergy of all to execute the press properly. Liverpool haven’t just stopped doing one or the other, they’re stopped doing both. Klopp’s Dortmund didn’t just stop doing one, they couldn’t do either.

Marco Reus wasn’t an attacking midfielder, despite Klopp trying to use him there. Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang wasn’t a right winger, despite Klopp trying to use him there. Ciro Immobile wasn’t (and still isn’t) a striker outside of Serie A.

Matthias Ginter wasn’t ready to play a starting role in a high line (though Neven Subotic was injured enough that Ginter didn’t have a choice in the matter), and despite Julian Weigl’s performances, they never had control of a game.

There is an interesting difference, though. Klopp’s Dortmund team kept pressing, they just didn’t win the ball enough in those pressing moments. Klopp’s Liverpool have simply stopped running. Per Dan Kennett of Anfield Index; they’ve been outrun in both distance AND high-intensity sprints in every game this season.

There was an astounding amount of luck that went against them, without a doubt. They were still the second-best team in Germany, as the expected goals went. But the intangibles got hold, and didn’t let go until Matchday 20, by which time Dortmund were losing to Augsburg and were in the relegation zone.

A Natural End to a Cycle

There is something that’s being whispered among Liverpool fans, too. Maybe, just maybe, this was inevitable. For Klopp, and his team, to keep going like they did, against the mechanical, soulless onslaught of Manchester City and a Premier League flooded with money, with other teams getting closer in the rear-view mirror, is a testament to their achievement.

To lose a Champions League final, then come back the following season and win it, only to lose the League title by a point, and then come back the next season and win it, shows tremendous mental fortitude. But it can’t last forever. Dortmund clung on, they tried to keep going, but one poor summer of recruitment and Klopp’s tendency to be overly loyal to players lay the foundations for the bad luck to fester.

The 2014 World Cup meant their pre-season was poor, injuries to Nuri Sahin, Ilkay Gundogan, and Marco Reus hampered their ability to field the same team regularly, and Henrik Mkhitaryan could not score for the life of him. But all this was simply the indicator that it was time to start again. Dortmund (well, Klopp himself in fact) elected to replace the manager, and keep the team.

Liverpool will likely make the opposite decision. But, if they want to ensure the bad luck doesn’t completely upend this season, Klopp and his team ought to think back on that fateful 2014/15 season, and ensure that the similarities – of which there are a distinct few – don’t rear their ugly heads again.

By: Alex Barilaro / @Alex_Barra12

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Matthias Hangst / Bongarts