The Rise and Fall of Bernard Tapie’s Marseille: Part 4: La Balance

This is the fourth installation of a six-part series on Olympique de Marseille. You can read “Part 1: L’homme d’affairs,” here, and “Part 2: La Nuit Les Projecteurs Se Sont Éteints,” here. You can read “Part 3: Nuits Blanches Et Thés Frelatés,” here. You can read “Part 5: Les Retombées,” here. You can read “Part 6: Le Mec de La Courneuve,” here.

Two years after the narrow defeat in Bari, Marseille headed to Munich to face off against Milan in the inaugural UEFA Champions League Final. The Rossoneri had returned from their European ban stronger than ever, having won all ten matches in the competition and conceding zero goals in the process. Nevertheless, Bernard Tapie remained determined to repeat his team’s triumphs in cycling and lift football’s most esteemed trophy.

The players entered the Olympiastadion pitch around 8:15 p.m. local time, as Tapie watched closely from a few seats next to Milan owner Silvio Berlusconi, the man whose footballing legacy Tapie had spent the past half-decade attempting to emulate. Milan lined up with a back four of Mauro Tassotti, Alessandro Costacurta, Franco Baresi, and Paolo Maldini, with Gianluigi Lentini and Roberto Donadoni manning the flanks. Leading the line for Milan was a 28-year-old Marco van Basten, who, unbeknownst to him, would play the final match of his footballing career that night.

Fabio Capello’s side dominated early proceedings, with Fabien Barthez forced to produce a string of world-class saves to keep Marseille alive, whilst Gianluca Massaro and Frank Rijkaard’s headers sailed just wide of the mark. The French side’s hopes were thrown into further disarray when center back Basile Boli pulled up with an injury and asked to be substituted, but just when Raymond Goethals was prepared to take him off, the Belgian received a call from Tapie, who told him to keep Boli on the pitch.

Abedi Pelé won a corner shortly before halftime, and the Ghanian stepped up and launched the ball into the box, where it was met with the head of Boli, who deflected it past Sebastiano Rossi and into the back of the net. It was Pelé, the man who Tapie had fabricated a widespread lie about being HIV-positive in order to ward off potential suitors and sign him for Marseille in 1987, and Boli, the man whose tears had strewn onto the Bari pitch in the wake of the 1991 Final, who combined to score the first goal in Champions League Final history.

They would hold on for the final 45 minutes and become the first, and to this date, the only French victor of the Champions League. Didier Deschamps hoisted the trophy, Tapie rode the shoulders of his players, and the streets of Marseille erupted in glory and ecstasy. That is, until two weeks later, when French detectives dug up an envelope containing 250,000 francs in the garden of Christophe Robert’s aunt.

A criminal investigation was soon opened, and when the Marseille players arrived in the Pyrenees for a pre-season training camp, 12 were taken away for questioning. Jean-Jacques Eydelie was arrested and charged with active corruption for providing the cash payment, Robert was charged with passive corruption for originally accepting the bribe before going back on his word, while his wife was charged with complicity. Jean-Pierre Bernès was initially taken to the hospital with heart problems, but when he returned, he too was charged with active corruption for his role in the deal.

Bernès was given a two-year suspended sentence and a fine of 15,000 francs ($3,000), and in 1994, he was banned for life from the French Football Federation (FFF), although this was overturned by FIFA in 1996. He has since become the most influential agent in French football, working with the likes of Franck Ribéry, Samir Nasri, Nabil Fékir, Laurent Blanc and Deschamps and enabling several of them to join Marseille.

The scandal sent shockwaves through the spine of French and European football, its aftermath affecting far more than just the principal actors in the bribery case. Disgusted with the corruption, Arsène Wenger departed his home country and packed his bags for Japan, where he would briefly manage Nagoya Grampus Eight before taking charge of Arsenal in 1996. Boro Primorac, the Valenciennes manager at the time, would follow his lead and serve as Wenger’s assistant over the course of the next two decades.

“We are talking about the worst period French football has been through. It was gangrenous from the inside because of the influence and the methods of Tapie at Marseille. I wanted to warn people, make it public but I couldn’t prove anything definitively,” stated Wenger in 2006. “At that time corruption and doping were big things and there was nothing worse than knowing the cards were stacked against us from the beginning.”

“Everybody knew they did it many times, bribing three players on one team. We were runners-up to them every year. We knew it was happening in France, although I was never approached to throw a game. I’m in football because I love football. I am happy that the players are earning a lot of money because I have always fought for that. But it has brought a lot of people to the game who don’t care about football, only money,” said Wenger in 2001.

Despite claiming that he rejected the offer after originally considering it, Jorge Burruchaga received a suspended six-month jail sentence and a two-year ban from footballing activities in France. He returned to his home country for his second spell at Independiente before retiring at 35 years of age, ending a storied career that had seen him score the winning goal against West Germany in the 1986 FIFA World Cup Final and participate in one of the most shameful scandals in footballing history.

Robert, who had buried the envelope in his aunt’s garden, received a two-year ban as well from the French Football Federation, and, like Burruchaga, was also handed a suspended six-month sentence. Both ‘Burru’ and Robert decided to head to Argentina to play in the Torneo Clausura, with Robert arriving to join Ferro Carril Oeste on a six-month contract with the option of a one-year extension.

“I had other proposals in Argentina, especially with a more upscale club, but if I opted for Ferro’s green jersey it is because I had given my word to the leaders long before. So even if I was offered more elsewhere, I preferred to honor my word,” stated Robert.

However, just a week before opening day, Robert was injured in a friendly against Inter Bratislava, only this time, he wasn’t faking it. The Frenchman would never once play an official match for the club, contending that the manager Rodolfo Motta never gave him a chance despite his best efforts to get fit, whilst asserting that the club failed to honor its wage promises.

Club president Felipe Evangelista rebutted his claim by stating that Robert’s stay at a glitzy Buenos Aires hotel had in fact left the club with a larger invoice to pay than that of his reported wage demands, whilst also stating that, unlike Burruchaga, who returned to Argentina after four days in France during the ensuing trial, Robert elected to spend several weeks in his homeland. Unable to gain a fresh start in South America, Robert spent a lone season in France’s fourth tier with Louhans-Cuiseaux FC before returning to Ligue 1 with AS Nancy. He would depart after just one season and joined Saint-Étienne, where he would make 24 appearances before retiring in 1999.

As for Eydelie, he was banned for a year from all footballing activity by FIFA and spent 17 days in prison, with the rest of his one-year sentence being suspended. Following the ban, he tried his luck at Benfica, but after failing to make a single appearance for the Águias, decided to head back to France and join Bastia. The journeyman would bounce around from Switzerland, England, and his home country, before hanging up his boots at Stade Beaucairois in France’s lower tiers.

Whilst he achieved moderate success as a manager in France, Algeria, Burundi and Côte d’Ivoire, Eydelie caused even greater headlines in 2006 when he released his tell-all book “Je Ne Joue Plus” (I’m Not Playing Anymore). Eydelie claimed that nearly all the Marseille players were involved in match-fixing and also stated that, with the exception of Bastia, he had engaged in doping in every single club that he had played at.

“Before the [1993 Champions League] Final, we were asked to stand in line and receive an injection. Rudi Völler was the only one to kick up a fuss. He went on yelling at everyone in the changing room. I had a dry mouth during the game. My body didn’t react like it would normally. Actually, the stuff inhibited me more than anything else. It was the first and last time I agreed to take something.”

Whilst Didier Deschamps and Marcel Desailly rejected the accusations that they had used performance-enhancing drugs, with the former even threatening to sue Eydelie for libel after he claimed that Deschamps had offered him a bribe to ‘take the foot off the gas’ during his time at Nantes, Irish international Tony Cascarino has claimed that he was injected with drugs during his time at Marseille.

“To this day I don’t have a clue what it was. The doctor would only tell me that it would give me an adrenalin boost and I never felt inclined to ask the rest,” stated Cascarino in 2003. “Whatever the substance was, my performances improved. I cling to the sliver of hope that it was legal, though in reality I’m 99 percent sure it wasn’t. I was fortunate that I was never caught. Most of the Marseille players were participating, so it seemed silly to decline and make a fuss.”

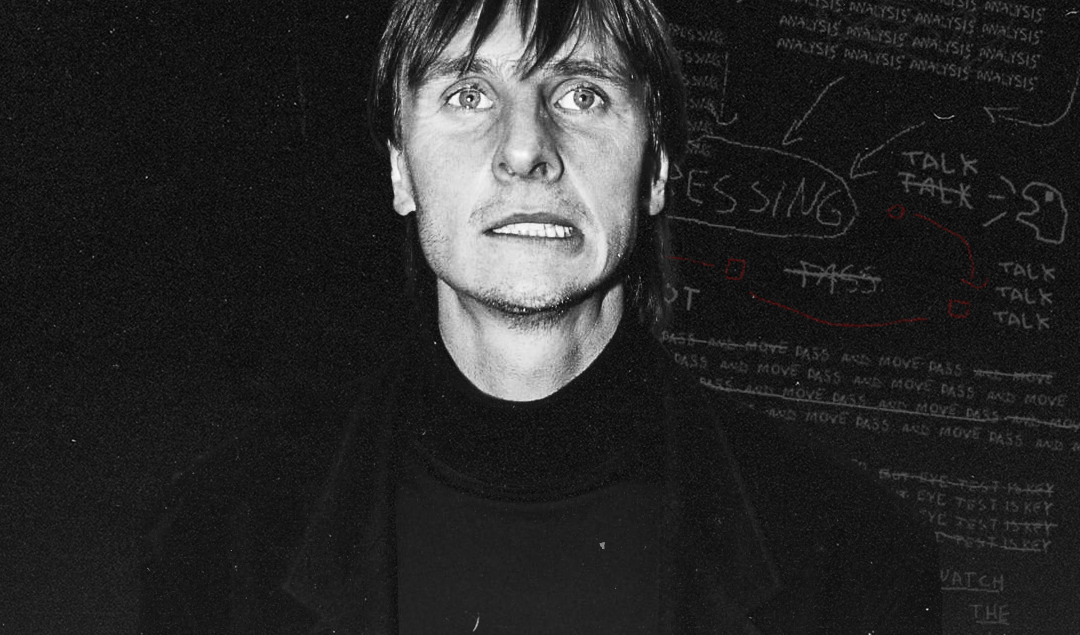

Jacques Glassmann would go on to receive the FIFA Fair Play Award in January 1996 for lifting the lid on the scandal, as well as a check for 10,000 Swiss francs, but his courageous actions were not received well with French fans. During the 1993-94 season, the whistle-blower was the constant target of whistling, booing, and death threats, often being referred to as “la balance” or “the scale,” “justicier” or “vigilante,” with Bernès sardonically dubbing him “Monsieur Propre” or “Mr. Clean.” Boro Primorac even decided to bench him in an away match against Nice so as to not rile the home supporters.

As Valenciennes struggled to adapt to life in the second division, Glassmann suffered an even harsher fate as a constant scapegoat, with fans spitting on him, hoisting uncharitable banners prior to each match, and jeering him whenever he touched the ball. On one occasion, whilst traveling for an away match against FC Gueugnon, a young boy handed him a coffin with his name written on it. This incident prompted Valenciennes to hire two personal bodyguards for his protection, and during the ongoing trial, the town hall placed two mobile guards by his in-laws’ house, where he had taken refuge.

With Valenciennes finishing 20th in the league and being relegated to the Championnat National, the club elected to not to renew Robert’s contract, although president Michel Coencas guaranteed him a ‘lifetime contract’ due to his honesty. No professional club was willing to take a chance on the national pariah, and at 32 years of age, Glassmann found himself without a club. He eventually joined Maubeuge in France’s fourth tier in October 1994, where he would stay for just one season.

Unable to deal with the constant flood of threats and harassment, Glassmann left France and headed to Réunion, a small island located approximately 340 miles east of Madagascar. Playing in the equivalent of the French sixth division, Glassmann continued to play football at Sainte-Rose whilst also holding a position at the municipal sports office, serving as a consultant for the local radio station, and coaching youngsters at the club in the U-16 and U-17 levels.

“Life was getting heavy in France. People kept telling me about the affair. In Reunion, they leave me alone….there were some very hard times. To be insulted, whistled, scolded on all areas of France, while we have told the truth … Anyone would have suffered from this situation.” After receiving his award and check from FIFA, Glassmann lamented, “I am not sure that my example makes others want to speak…The truth is not always good to say.”

Glassmann headed back to his homeland in October 1997 with the desire of becoming a manager, but despite receiving his coaching licenses, he did not receive any offers apart from a brief spell at Strasbourg that ended after a month. When Daniel Tantot, the president of the “Allez VAFC” fan club sought to rename the Valenciennes town hall after Glassmann, he was shouted down by the town hall members.

After struggling with unemployment, Glassmann finally received a job offer from the Union Nationale des Footballeurs Professionnels (UNFP) in January 2002, where he was responsible for helping footballers who were nearing the end of their careers find a job, and he continues to work at the UNFP to this date. Six years later, Glassmann received another position from French football’s governing body, the Ligue de Football Professionnel (LFP), where he tracked down unsportsmanlike behavior in football matches.

“Some people agree to be bought, not me,” stated Glassmann in his 2003 autobiography “Foot et moi la paix” (Football and me the peace). “It was said that I had betrayed my sport, my team. On the contrary, I consider that I have rendered service to football, to my team, and even to OM. I was playing at a club that was struggling with its guts to stay in Ligue 1, and I was asked to make them lose for money. If I had done it, I would have betrayed the supporters, the inhabitants of an entire city.”

By: Zach Lowy

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Pool Bassignac / Turpin / Gamma-Rapho