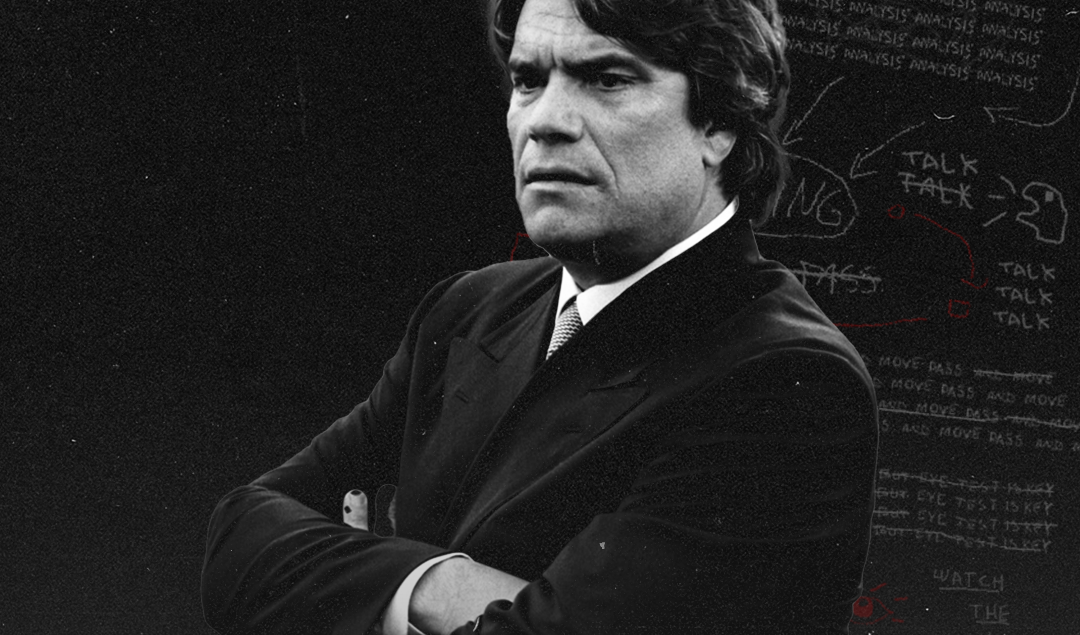

The Rise and Fall of Bernard Tapie’s Marseille: Part 1: L’homme d’affaires

This is the first installation of a six-part series on Olympique de Marseille. You can read “Part 2: La Nuit Les Projecteurs Se Sont Éteints,” here. You can read “Part 3: Nuits Blanches Et Thés Frelatés,” here. You can read “Part 4: La Balance,” here. You can read “Part 5: Les Retombées,” here. You can read “Part 6: Le Mec de La Courneuve,” here.

Since its founding in 1899, Olympique de Marseille has established a reputation as one of the most successful, popular, and ambitious clubs in French football. However, in the spring of 1986, they were on their knees for a savior to rescue them from a crisis that had been brewing for over a decade.

The troubles began 14 years prior with the departure of club president Marcel Leclerc. After the French Football Federation rejected the signing of Hungarian striker Zoltán Varga, whose arrival would have seen Marseille surpass the foreign player limit of 2, Leclerc threatened to withdraw the club from Ligue 1 entirely. Instead of backing Leclerc, who had presided over a glorious period that saw Marseille return to the top flight and accumulate a total of five trophies, they gave him the ax.

The years that followed Leclerc’s unceremonious exit were filled with uncertainty, regression, and soon, despair. Marseille were relegated in 1980, and the year after, they were forced to declare bankruptcy and sell their entire squad, Marseille remained in the second tier for the next four years until winning promotion with a ragtag group of young footballers from the academy, commonly referred to as ‘Les Minots.’

After narrowly escaping the drop in their first season back in the top flight, Les Phocéens found themselves embroiled in another relegation fight midway through the 1985/86 campaign. With the club in desperate need of an affluent owner to return them to the promised land, Marseille mayor Gaston Defferre turned to a middle-aged Parisian businessman by the name of Bernard Tapie, who purchased the club for one franc, or 14 pence by today’s conversion rate. Under Tapie’s reign, Olympique de Marseille would enjoy their most glorious night, before suffering the darkest period in club history.

Born to a metalworker and a cleaner in the Parisian suburb of Le Bourget, Tapie’s first big break came at 21 years of age when he won a singing contest at Saint- Jean-de-Monts on the Atlantic coast, a triumph that motivated him to pursue a brief yet mildly successful career as a pop singer. In 1966, under the stage name of Bernard Tapy, he reached commercial success by recording “Passport pour le soleil,” a French adaptation of “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” a patriotic song used to motivate American military forces during the Vietnam War.

Shortly after, Tapie decided to follow his childhood dreams of becoming a racecar driver and began racing in Formula 3, until a severe accident left him in a coma for two weeks and ended his fledgling sports career. He quit the music industry in 1976 and spent a year in the United States, absorbing the capitalistic mantras of the era, before returning to France as a determined business consultant. Tapie decided to pursue a livelihood of buying and selling companies that were on the brink of bankruptcy, using his business tacit and large-scale lay-offs to churn massive profits for himself. Between 1977 and 1990, he purchased over 40 companies, amassing a fortune of 2 billion francs.

Basking in his newfound affluence, Tapie soon decided to make inroads into the sports industry; in 1983, his health food chain La Vie Claire founded the La Vie Claire cycling team that would go on to win multiple Tour de Frances. In 1985, he bought “Club Mediterranee,” the longest sailing ship in the world at the time. Tapie renamed the yacht “Phocea,” and three years later, his crew broke the world record for crossing the Atlantic Ocean, sailing 2,810 miles in 8 days, 3 hours and 29 minutes.

Much of Tapie’s early life is intentionally obscured. Despite hailing from the middle-class community of Le Bourget, he has erroneously claimed that he grew up in the despondent slum of La Courneuve. He repeatedly stated that he had attained an engineering degree, but he had never even graduated from high school. He claimed to have been born in 1946, rather than his actual birth date of 1943, a lie magnified by the countless botox injections he would receive in his middle age. He has also stated that he possesses an engineering degree, but the research of various journalists proves that he never even finished school.

By the mid-’80s, Tapie had become a household name in France, having peddled his wealth into a weekly television show called “Ambition” that motivated burgeoning young entrepreneurs to start their own businesses, in a similar fashion to modern-day reality television shows in the United States such as Shark Tank or The Apprentice. “He was Trump before Trump, a typhoon of populist charisma whose Hollywood smile was paired with scheming brown eyes,” wrote Christopher Weir of These Football Times.

Like Donald Trump, Tapie soon discovered that it did not suffice to have deep pockets and a pervasive cultural influence; the real power came in politics. He took note of his country’s ongoing malaise — racial tensions, a high unemployment rate, anti-immigrant sentiment — and realized OM’s potential as a vehicle for political gain.

He realized that he could peddle millions of his increasing fortune into the football club and revive a fallen giant, whilst simultaneously currying political favor with the Marseille community. It’s why, after originally rejecting the offer on the basis that he “knew nothing about football,” Tapie decided to purchase Olympique de Marseille on April 12, 1986 for a symbolic single franc. He would have been swayed by the words of mayor Gaston Defferre, who told him, “I’m not selling you a team, I’m not selling you a stadium – I’m selling you a public.”

After the club narrowly stayed up in Ligue 1, Tapie’s first order of business was bringing in Michel Hidalgo as his director of football, two years after Hidalgo led France to their first ever international title in the 1984 European Championship. With Tapie’s generous financial backing and Hidalgo’s expertise, Marseille purchased Jean-Pierre Papin, the breakout star of France’s run to the semifinals of the 1986 FIFA World Cup in Mexico, Jean-François Domergue and Alain Giresse, two key performers in France’s Euros triumph, and West German defender Karlheinz Förster, widely considered to be one of the best markers of his generation.

The Mercurial Talents of Jean-Pierre Papin, a Forward of the Highest Quality

Bolstered by their star-studded cast, Marseille bounced back from their 12th-place finish from the previous season and skyrocketed up the Ligue 1 table, only to lose the title by a whisker to Bordeaux. They defeated Lyon, Lens and Reims en route to the Coupe de France Final, where they would lose to Bordeaux at the Parc de Princes via goals from Philippe Fargeon and Zlatko Vujović.

Undeterred by the club’s near-misses, Tapie continued to pour millions of francs into the transfer market, as Marseille brought in Ghana attacking midfielder Abedi Pelé, France defender Yvon Le Roux, and Germany striker Klaus Allofs. To secure the signing of Pelé from FC Mulhouse, Tapie had advised the Ghanaian to refuse to take a blood test during his medical at AS Monaco, whilst also contriving with a Monaco employee to fabricate a lie that Pelé had contracted HIV.

The fear of an HIV-positive player during the height of the AIDS epidemic was enough to put off Monaco’s interest and allow Marseille to swoop in and purchase him with zero competition. “It’s like that. You have to win at any cost. I am ashamed of myself now but we have to accept what we are, with the good and the bad,” Tapie revealed in 2017. It was to little avail, though; Marseille finished 6th in Ligue 1, although they did reach the semi-finals of the Cup Winners’ Cup before losing to a Dennis Bergkamp-led Ajax side.

Desperate for results, Tapie sacked manager Gérard Banide and replaced him with Gérard Gili, a former goalkeeper who had begun and ended his playing career with Marseille. The flamboyant owner continued to reinforce the squad with the signings of Franck Sauzée, Gaëtan Huard, Bruno Germain, and Philippe Vercruysse, whilst bringing in a 22-year-old forward from Auxerre by the name of Eric Cantona. As Marseille prepared for the upcoming campaign, Tapie braced himself for a new battle: this time, in the ballot box.

When Jean-Marie Le Pen, president of the far-right National Front party, announced his candidature for a congressional seat in the Marseille area, Tapie decided he needed to intervene. Le Pen had achieved notoriety for his hard-line stance on immigration, once saying, “I have come here because I have the solution to your problems – deport the immigrants and the streets will be safe and jobs plentiful.”

Whilst Le Pen aimed to latch onto the growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the region, Tapie attempted to curry favor by showing off his ostentatious lifestyle, touting himself as a self-made millionaire who could inspire a new wave of rags-to-riches stories. “As the era of Reagan and Thatcher unfolded elsewhere, Tapie was the only man in France preaching the creed of free enterprise, and how to make it work in a culture controlled by class barriers and red tape,” wrote Louise Baring in The Independent. “With his Porsches and his private jet, complete with corporate logos, he became the living embodiment of the profit motive.”

The debates between Le Pen and Tapie produced plenty of fireworks and flashy headlines, but after 300 votes had somehow vanished in the first election, Tapie won the re-run in January 1989 to become the Socialist Deputy for the Bouches-du-Rhone region.

On the pitch, meanwhile, things were turning around for Marseille. After picking up just 1 win in their first 7 matches, Gili’s side had ascended to the top of the table on the back of Papin’s 22 goals in the league campaign. They would go on to finish two points above Bordeaux in first place, ending a 17-year title drought and defeating Arsène Wenger’s Monaco in the Coupe de France Final.

Conquering French football in three short years only exacerbated Tapie’s insatiable appetite for European silverware, who continued to invest heavily with the signings of Didier Deschamps, Enzo Francescoli, Alain Roche, Carlos Mozer and Jean Tigana. He nearly managed to snatch Diego Maradona away from the Partenopei, but when Napoli president Corrado Ferlaino pleaded with his Argentine superstar to go back on his word, Maradona reneged on the deal. Instead, Marseille ended up signing Chris Waddle from Tottenham Hotspur for a fee of £4.5 million, the third-highest transfer fee in football history at the time.

The following year confirmed Marseille’s position on the domestic stage, as Les Olympiens edged Raymond Goethals’s Bordeaux to the league title. The real drama, however, came in Europe: after eliminating Brøndby, AEK Athens and CSKA Sofia, Marseille faced off against Benfica in the semifinals of the European Cup. A 2-1 victory at the Stade Vélodrome had brought them within touching distance of their first-ever international final, and they looked well on their way to booking their ticket to Vienna until the 82nd minute of the second leg.

Benfica striker Mats Magnusson connected on Valdo’s inswinging corner kick with a glanced header, spinning the ball into the direction of Vata, who used his forearm to deflect the ball into the back of the net. The Estádio da Luz erupted with red flares and triumphant cheers, cathartically celebrating a goal that should have never been awarded in the first place. Marseille were robbed of a place in the Final, and Tapie vowed for revenge. “I learn quickly. That will not happen to us again.”

By: Zach Lowy

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Neal Simpson – EMPICS / PA Images