When Dictators Stepped in the Way of Big-Money Transfers

Whilst doing research for an article about the decline of Romanian football, the story of Nicolae Dobrin came up. He was a brilliant footballer whose career began at 14 and he helped his fairly unknown site, Arges Pitesti, defeat the mighty Real Madrid in a European Cup tie. This prompted the Spanish club to make a bid to sign him, but the country’s dictator Nicolae Ceausescu blocked the move.

This story has sent me on a path of trying to find out which other players were prevented from sealing a possibly dream move by a tyrannical regime. I hope this offers a stark contrast to the drama and histrionics of today’s players who throw their toys out of the pram every time their clubs decline them a so-called “dream” move.

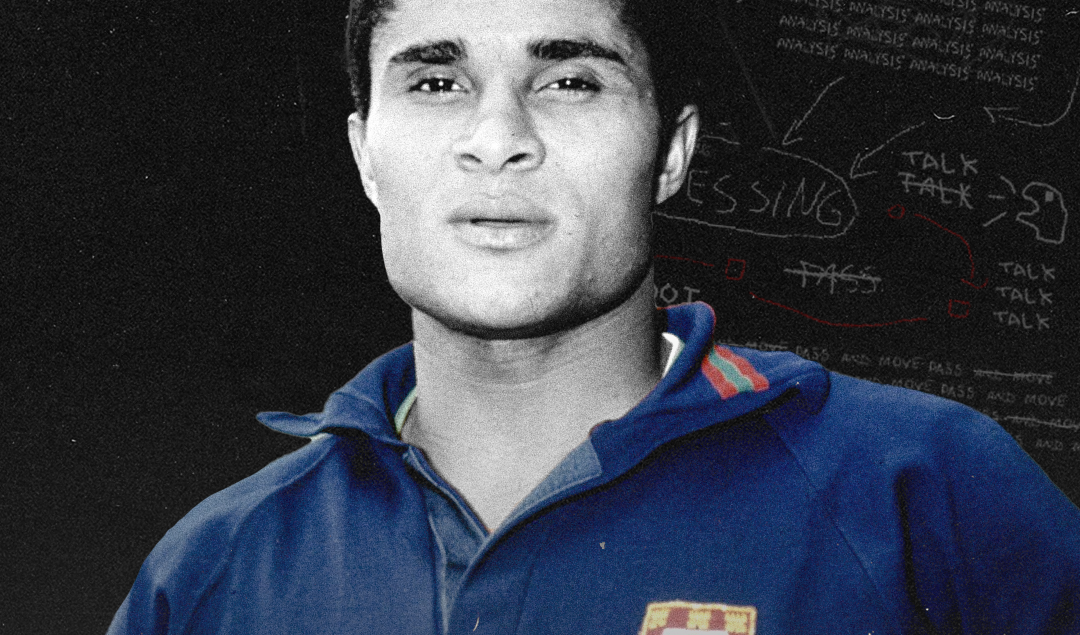

Eusebio

As in most cases, the humblest of backgrounds produce the most precious diamonds and Eusebio was no different. His life began in Maputo, which was part of Portuguese Mozambique at the time. He honed his skills on makeshift pitches with balls made from socks stuffed into newspapers and applied for a trial at Grupo Desportivo de Lourenço de Marques, a Benfica feeder team. Since he was rejected without any form of trial, young Eusebio went to local rivals Sporting Clube de Lourenço Marques, which was a Sporting feeder club.

His talent shone through and soon enough they were reported to legendary Benfica coach Bela Guttmann. The first transfer controversy of his life ensued. Benfica made an approach to his family offering a paying contract and the family agreed. Sporting were none too pleased that the brightest talent in their feeder team was snapped up by their biggest rivals and contested the legitimacy of the move.

A story fit for a spy thriller ensued, where Eusebio was given the codename Ruth Malosso and moved to a safe house in the Algarve with three bodyguards. He was kept safe until May of 1961 when his move to Benfica became permanent. Four Portuguese titles, one European Cup, one Ballon d’Or and a third-place finish at the 1966 World Cup followed. In the summer after the World Cup, La Grande Inter came calling, looking for Eusebio’s talents to help them secure a third European Cup.

As was the case with most athletes living in repressive states, Antonio Salazar declared Eusebio a national treasure and scampered a move that would have seen the player earn his year’s salary at Benfica in one month in Milan. Luckily for the Portuguese people, the 1974 Carnation Revolution deposed Salazar’s regime, four years after the dictator’s death. For Eusebio however, it was rather late, as he could only secure a move to the United States.

Pele

On December 29, we lost Pele, arguably the greatest footballer of all time. One criticism that is often thrown at O Rei is that he did not show his talents on the European stage. Although the Brazilian game in the 1960s was easily on par with the European game, the casual xenophobia found amongst many European football fans prompt them to take this fact into consideration when discussing the moniker of the greatest player of all time. However, history could have been much different.

You cannot spend your playing career scoring obscene amounts of goals, making whole defensive units look like toddlers and winning three World Cups without attracting interest from the greatest clubs in the game. Many clubs have been linked with the Brazilian magician, Real Madrid, Inter, Juventus and Manchester United amongst them. Whilst many links could be mere fabrications by overzealous journalists two of these bids have an actual story behind them. Years before Inter’s Helenio Herrera failed in his bid for Eusebio, one million dollars was offered to Santos for the services of Pele.

One year later the president of Juventus and Fiat travelled personally to Brazil to negotiate a transfer, which involved Pele receiving shares in the automobile manufacturer but returned empty-handed. The reason for both these rejections was state interference. Despite not being a dictator, President Jânio Quadros was acutely aware of the importance of football to his electorate and the importance of Pele to football. And with his support dwindling after a series of failed reforms and dubious decisions (which included banning bikinis) he signed a decree which named Pele as a national treasure that could not be removed from the country.

Argentina and France’s Road to the World Cup Final: Part One — France’s Early Beginnings

His term would not last much longer, but Quadros’ successors never thought of revoking the decree, instead only reinstating the bikinis. Pele’s big money move would come many years later, at 35 after his retirement from Santos. Ever the gentleman, whenever he was asked about those transfers Pele would smile and say he did not ever think of leaving Santos at the peak of his powers.

Zaire 1974

Our next inclusion covers a whole squad instead of just one player. Zaire’s dictator President Mobutu, who was, let’s be honest, a massive prick, also had an unfortunate influence on his country’s footballers. After coming to power, he recalled all Zaire-born footballers back to the internal championship with the aim of creating international fame for his new country through football. As he was a man you could not refuse Zaire’s players returned and with a fully home-based squad they won the 1974 African Cup of Nations.

The team would also take part in the 1974 World Cup, where a strong showing was expected. Despite playing an exciting brand of attacking football, the first game ended in defeat against the Scots. The next game saw them take on Yugoslavia, but a major issue unfolded before the game. Their supreme leader had sent a large entourage with them to Germany and quite a sizeable sum of money, which should be used both for the team’s salaries and to give the impression of wealth and success.

Like any self-respecting parvenu, the Zaire delegation blew through the whole budget, meaning their players would not be paid for their next games. A boycott took place, in the form of a 9-0 loss to Yugoslavia and FIFA had to intervene and pay the players themselves. Back in Zaire, Mobutu, apoplectic with rage, sent his henchmen to threaten the team at their hotel in Germany.

The whole hotel was closed off and after a tirade of abuse and threats; the players were warned they would not be able to return home if they lost to Brazil by more than four goals. Disaster was avoided in spectacular fashion in the next game, with one Zaire player hoofing the ball up the pitch as the Brazil players lined up to take a free kick. In later years football did not occupy such a prominent role in the dictator’s thoughts and his reign of terror finally ended in 1997.

Wlodimierz Lubanski

Before Robert Lewandowski, there was Walodimierz Lubanski. He is the second-highest scorer of the Polish national team and is considered one of the best Polish footballers. In his early career with Gornik Zabrze he impressed not only the Polish public but also managers like Sir Matt Busby and Helenio Herrera. The latter coached him in a charity game in Basel in a Europe team that faced the South American team.

After the game two Real Madrid players, who were on the pitch with him that night, tried to convince him to join their ranks. Lubanski was skeptical his regime would allow him to leave but held out hope. Sometime later in 1972, Madrid’s representatives travelled to Warsaw with a million-dollar offer but the representatives of the communist party refused them.

Apparently the reasoning was: What would Moscow say? His career was negatively impacted by this failed move, as he sustained a knee injury, which was poorly treated by the incompetent doctors assigned to him. To this day he states that he was simply a regular mediocre player after the injury.

The Mighty Magyars

In the 1950s, Hungary was one of the most feared teams on the European footballing landscape. Their proto Total Football and WM formation ensured they were a daunting prospect for every opposing team and one only has to look at the 1954 World Cup final to understand how good this team was. They literally had to name that game The Miracle of Bern to encompass the shock that West Germany sent throughout the world of football by defeating the Hungarians.

But whilst the footballing side of things was as rosy as it gets, the internal politics of the Hungarian state were a bleak affair. On the losing side of World War Two and with a long history of revisionism and far right-leaning tendencies the repression introduced by the Soviet-backed regime was as high as it could get. Unlike countries situated further East, Hungary bordered Austria, which was rescued from the clutches of one of the most disgusting human beings to walk this earth.

Despite the world being rid of Joseph Stalin for three years his successors were just as repressive as him. Not content with making the lives of their own citizens miserable they sent troops to suppress the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. This event saw the country’s most important team, Budapest Honved away on European Cup duty. Many of the players refused to return to the country, even with the government threatening their families.

After a fundraising tour, they returned to Europe where they parted ways. Players like Ferenc Puskás, Sándor Kocsis and Nándor Hidegkuti decided to defy the regime and found clubs in Western Europe whilst others returned home. Honved was, back then, the sports club of the armed forces and contained the core of the Mighty Magyars but its assembly was mired in controversy. Since the communist takeover, the club received license to raid other clubs, especially Ferencvaros, which had right-wing leanings.

From there, they recruited Sándor Kocsis, Zoltán Czibor and László Budai. The team’s goalkeeper Gyula Grosics attempted to leave the country and was arrested and later set free, after which he also miraculously joined Honved. Two more footballers have attempted to escape their tyrannical regime with opposite levels of success. Laszlo Kubala left his country in 1949 and despite FIFA siding with the despotic regime (as they so often like to do) and banning him for a year he went on to find success with Barcelona.

Sadly, our next inclusion lost much more than a dream transfer at the hands of his regime. Sandor Szucs was a defender that won three titles with Ujpest FC and played with some of the members of the Golden Generation on the international stage. In 1948 he started a relationship with pop singer Erszi Kovacs, but since she was married the state did not take their relationship easily.

With Szucs at risk of losing his status as a footballer if he continued his romantic affair, the couple found a handler who promised to help them escape to Austria. Since Kubala’s defection, the state was much more careful in regard to their athletes and their handler proved to be an agent of the state police. The couple were taken into custody and since Szucs played for a club affiliated with the police, he was found guilty of treason and executed. Every year a youth football tournament is held in his honour.

By: Eduard Holdis / @HE_Ftbl

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / MirrorPix