Clermont Foot – Ligue 1’s ‘Other’ Overachievers

Ligue 1 is a division of disparity. The top side, PSG, possess a squad worth about £760 million, whilst the poorest side is worth approximately £23 million. What this means, however, is that the division is a perfect environment for underdog stories, everyone’s favourite kind. Most will be aware of RC Lens’ outstanding run over the last two seasons, securing second place this year and Champions League qualification. There is, however, another punchy overachiever in France this year, in the form of Clermont Foot 63.

Who? And Why Should I Care?

Clermont were promoted from Ligue 2 just two years ago, surviving last season by the skin of their teeth despite being firm favourites for the drop. This year, they’ve continued their upwards trajectory, playing a pragmatic brand of football and recruiting with great intelligence. Clermont really are tiny. They rank second bottom in the aforementioned squad value ranking, with a total of just £32m.

For perspective, when compared to English clubs they are valued by Transfermarkt as equivalent to Reading and Blackpool, two clubs that will play in the third tier next season. Despite this, Clermont finished 8th in Ligue 1. A remarkable overachievement, placing them above established clubs such as Nice, Reims, Montpellier and Toulouse. A club with a stadium, the Stade Gabriel Montpied, which holds under 12,000, ended up just eight points away from European competition, turning over PSG at the Parc des Princes in the process.

Foundations: Recruitment

Clermont have put to shame some of the far bigger clubs below them, with a campaign built on smart recruitment. The summer saw a high volume of squad turnover, with some of their most important players moving elsewhere. The two most vital losses were 14-goal striker Mohamed Bayo, who went to Lille for £12 million, whilst young midfielder Salis Abdul Samed was snapped up by the equally intelligent Lens.

Salis Abdul Samed: The Ghanaian Midfielder Making Strides at Lens

In total, six first-team players left the squad, to the tune of about £19m. To replace them, roughly £2m was spent with remarkable effectiveness. The arrivals which have played the biggest part include goalkeeper Mory Diaw, Genk left wing-back Neto Borges, his right-sided equivalent Mehdi Zeffane and loanee Belgian centre-back Maximiliano Caufriez. All of these players have been starters this season and all arrived for free.

One of the most exciting additions this season has been a player who was already on the books. Austrian forward Muhammed Cham returned from a spell at affiliate club Lustenau, in the Austrian second tier which saw him chalk up 27 goal contributions. A return of 10 from 21 starts in his first Ligue 1 campaign represents a promising step-up considering the steep increase in quality. All in all, undergoing such a high amount of disruption, making that much profit from the window, and ending up eight points away from Europe is a remarkable achievement.

Foundations: The Coach

A large degree of the credit for this must therefore go to the manager. There are multiple things that both Pascal Gastien and Clermont Foot have in common. Both arrived in Ligue 1 and remain there against the odds, both are brilliantly pragmatic and both are overachievers.

Gastien was an internal promotion at Clermont, given the first team manager’s job having been in charge of the club’s B team. Before this, a respectable, if unremarkable coaching career spent primarily in Ligue 2 did little to indicate a season like this on the horizon. Now 59 years of age, Gastien is duelling with France’s top clubs having arrived via unconventional means, just like Clermont itself.

The connection is also enhanced by arguably their most important player, Johan Gastien, son of Pascal. Gastien Jr is something of a quarterback for Clermont, often found dropping alongside defenders to assist in the build-up, before picking a forward pass to launch Clermont’s attacks. He’s capable of guiding his teammates and executing tactical instructions accurately, as I suppose he should be.

Often paired with Yohann Magnin or the vastly experienced Maxime Gonalons, Clermont’s midfield is adaptable and responsible for executing a mid-block, cutting out interior passing lanes and daring the opposition to play riskier balls elsewhere. Clermont protect the centre, aiming to intercept or to simply frustrate their richer and higher quality opponents.

Once possession is won back, their shape tends to look something like the above, a 3-4-2-1 formation. The specific personnel is of course subject to change depending on the opponent in question, but the general principles remain the same. Clermont’s wing-backs are of vital importance to their pragmatic approach, with their positioning able to change a five-man defence into a five-man attack with ease.

Clermont’s attacking output remains similar in volume to last year, but has changed somewhat in nature. A team not blessed with elite creative talents, or able to exert real control over games, Clermont pride themselves on being opportunists and this is reflected somewhat in its offensive data. An expected goals total of 47.5, having actually scored 45, is only good enough for 13th in the league, despite their eventual finish in 8th. Clermont simply don’t create very much. When they do get chances, however, they tend to take them, as shown by the close difference between expected goals and actual output.

How Do They Attack?

The nature of the chances created has changed somewhat, mostly on account of the new profiles added to the squad. Previously, the presence of Mohamed Bayo led Clermont to frequently target wide areas, with a view to getting crosses into the box. Clermont still look to progress the ball this way, but their chances are created slightly differently.

Without the asset of Bayo in the box, as well as the new presence of more gifted ball carriers such as Cham, Borges, Zeffane and the increased influence of Tunisian playmaker Saîf-Eddine Khaoui, has meant that Clermont now look to enter the box via more precise passes and carries, rather than hopeful crosses.

Aos 25 anos, Neto Borges já começa a mostrar o seu talento como um dos mais promissores laterais esquerdos da Primeira Liga com o Tondela de Pako Ayestarán.

Falei com o jogador brasileiro numa entrevista exclusiva de @BTLvid.

— Zach Lowy (@ZachLowy) November 6, 2021

This has meant that they are far more efficient in their chance creation. Crosses are often easier to defend and are actually quite hard to perform effectively. A large volume of such passes is required to yield any significant return. The introduction of more technical ball carriers allows Clermont to penetrate the box with the ball at their feet, causing chaos and generating better opportunities with a clear sight of the goal.

They will still generally enter the box from wide areas, as their wing-backs allow them to progress into these spaces. Once in the box, however, they will now look for more cutbacks along the ground, quick incisive passes, either directly across the box or a reverse pass into the feet of an onrushing attacker.

A great example of this can be seen in their 2-0 win against Lorient back in May. The move begins in the aftermath of a penalty save from keeper, Mory Diaw. He looks upfield to start an attack and opts for a long throw, finding the feet of left wing-back Neto Borges.

Borges receives the ball and immediately looks to drive at the opposition, embarking on a brilliant direct run which draws the attention of three Lorient players. This is something commonly seen in Clermont’s build-up, with Borges acting as a ‘wide receiver’ of sorts, to use an American Football term.

This allows him to slip through a perfectly weighted pass to the left-sided forward, in this instance the young Aïman Maurer, who drives into the box. Borges’ fast and direct play has opened up gaps in the Lorient defence, perhaps slightly on its heels due to the penalty drama just seconds earlier.

Upon arrival in the box, Maurer is faced with multiple options for the cutback. Two forwards, in Khaoui and Kyei, but also the right wing back, Mehdi Zeffane. This is not uncommon for Gastien’s side, with the wing backs often given licence to join the attack and pop up in dangerous situations, often causing chaos in the box and drawing defenders.

Maurer finds the feet of Khaoui, who is unmarked partly thanks to his teammates’ accompanying runs, and finishes the move.

This is a great example of how Clermont create opportunities. From the keeper’s hands to the opposition net within twelve seconds, an emphasis on speed is clear to see, as well as direct passing and progressive carries in wide areas. What’s even more typical of Clermont is the game state in which it was scored.

Directly after a penalty save which kept the scores level, just a minute before half time, Clermont sensed an opportunity to capitalise on the opposition’s disorganisation, as they were still repositioning themselves and distracted. Clermont’s record this season is partly built on sensing these opportunities and capitalising on them. Without top-quality players, they have to take whatever they can get.

Marginal Gains

Clermont contest most games against teams with superior players, forcing them to play with their backs against the wall. Part of closing this gap in quality and snatching results is through seeking marginal gains of sorts, doing what they can to disrupt the rhythm of the opposition and therefore break their control of the game.

A particularly interesting example of this is shown through Clermont’s number of fouls won compared to other teams. This season, Clermont drew 592 fouls, with the next highest being 523 and third having 501. This is an immense number of fouls by any standard, miles clear of a majority of teams in the division. Clermont are exceptionally good at getting kicked, it seems.

The advantages of this for a small club are evident. Clermont can disrupt the flow of the game, winning set pieces from which to retain control of the ball or deliver a dangerous ball to their physical threats in the box. This is facilitated by their propensity for fast counterattacks, the presence of players happy to run directly at the defences, as well as a number of savvy professionals with years of experience in a league now known for its rugged approach to defending. Clermont are more than aware of what referees are looking for.

Pragmatism and Opportunism

This focus on seizing their moments also shows itself in Clermont’s out-of-possession approach. They employ a mid-block, happy to press when the opportunity arises, particularly against defences who are slightly dodgy with the ball at their feet. Primarily, Clermont defend the centre of the pitch, packing the box and forcing opponents into unfavourable wide positions.

This is shown in the below example from the visit to Auxerre. It’s clear to see that Clermont have retreated to a 5 man defence, with the wing-backs aligning with the centre-backs. What is interesting here is the use of a ‘box’ midfield, with the two centre midfielders sitting behind the two wider forwards, who have taken up narrower positions in this phase.

This makes the formation more of a 5-2-2-1, allowing for effective zonal marking in the centre of the pitch and often outnumbering opponents’ three-man midfields. This can also generate effective counter-attacking opportunities, leaving creative players between the lines and at good angles to receive a diagonal pass on the break.

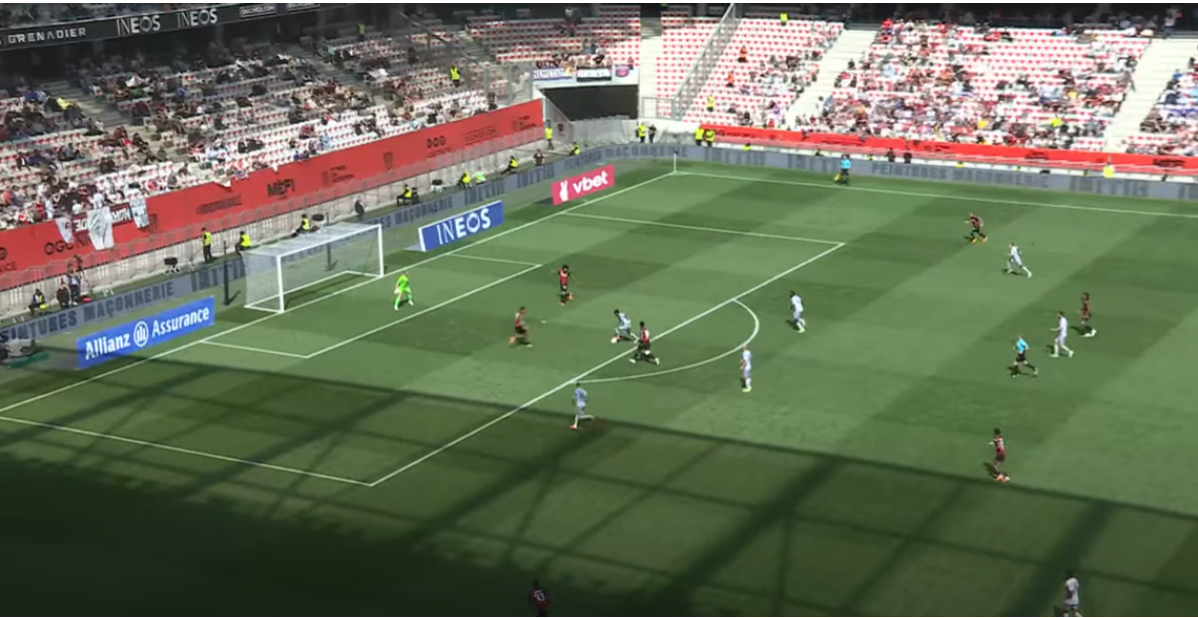

On this occasion, Auxerre were unable to progress centrally, with all passing lanes blocked by a Clermont man. The centre-back resorts to a risky long ball to the wing, just where Clermont want it. It’s defended and a goal kick results. The two ‘wide’ forwards’ out-of-possession responsibilities don’t end there, however. In the below example, we can see another manifestation of Gastien’s pragmatic approach, from an away fixture against Nice in April. The Nice goalkeeper, Kasper Schmeichel, is looking to play into midfield from a goal kick.

Clermont are aiming to box Nice in, with their three forwards, Elbasan Rashani, Grejohn Kyei and Muhammed Cham positioned aggressively, taking away the option of passing to either centre back, who would be placed under immediate pressure. Schmeichel opts for a riskier pass directly through the Clermont press to his defensive midfielder, who receives and looks to turn.

However, he is faced with an onrushing Clermont midfielder almost immediately, in the form of captain Johan Gastien. He nicks the ball away from the Nice midfielder, with striker Gyei offering supporting pressure from behind.

He’s left with a simple pass into the feet of Cham, who shows great composure, rounding his man and finishing brilliantly with his left.

This goal of course demonstrates how bad Nice are at building from the back. A goalkeeper as experienced as that should simply not play that pass, putting its recipient under so much immediate pressure. Yet, it also shows Clermont’s intelligence. They are not known as a high-pressing team by any means, but as shown before, they are opportunists.

Perhaps in the knowledge that Nice are slightly dodgy from the back, they shut off the easy options, inviting Schmeichel to either kick it long, where Clermont’s three centre backs stand a good chance of winning the header, or play a riskier pass into midfield. He opts for the latter, falling straight into the trap. Clermont pounce with perfect timing and reap the rewards, having placed their best attacking threats high up the pitch to take immediate advantage.

Players To Keep Tabs On

To finish, a mention to a few players who might be worth keeping an eye out for this summer. Clermont’s squad has been built with intelligence and efficiency but is founded upon its fair share of seasoned Ligue 1 campaigners, who are overperforming to be at this level and are unlikely to move for any great fee. But this is not to say that there aren’t players in the squad who may be targeted by larger clubs this summer. One might be Muhammed Cham, who’s come up a fair bit during this piece. As previously mentioned, 10 contributions in 21 starts, in his first go at a top-five league is not to be sniffed at.

His is a unique profile too, an attacking midfielder most comfortable in a narrow three. Highly proficient in the final third, an intelligent presser with great composure in front of goal and an effective playmaker. He’s already been capped at senior level for Austria and at only 22 years old, he could be seen as a player worth taking a punt on for a relatively low-risk price.

Joining him on the radar of other European clubs will likely be 23-year-old Ghanaian defender Alidu Seidu. Primarily a centre-back, but also capable of playing as a right-back, he’s ideal for a role on the right side of a back three, where he’s featured 22 times this season, overcoming a period out injured and a promising trip to the World Cup. He possesses good fundamentals, a proactive defender in the 90th percentile for interceptions among his peers.

The Ghanaian often steps out of the back line to attack the ball, necessary to make up for his small stature at just 5ft 8in. Seidu also compensates for this by offering a great outlet in the build-up, happy to take up higher positions to receive progressive passes and carry it forward. He’s in the 99th percentile for successful take-ons, although this is influenced by his 6 games at right-back this campaign. That position might be where his future lies, but there is plenty to like as a centre-back with a unique profile and some might be tempted.

Other departures might include left wing-back Neto Borges. A shrewd pick-up in the summer, who has demonstrated an ability in transition which could be highly coveted. Still only 26, in the last years of his deal and in the 90th percentile for successful take-ons, Borges might attract the attention of clubs looking for a ‘wide receiver’, as his role might be best described. There may also be interest in academy graduate Aïman Maurer. At just 18, some might look to secure him early, but with just 10 league appearances, albeit highly promising ones, he’s probably still in need of a ‘breakout’ campaign.

As last summer demonstrated, whoever attracts interest, the message is clear that no player is off limits. Should the price be deemed appropriate, Clermont will sell. They back themselves to replace any player in the squad at a fraction of the price and proved this last time out. Coach Gastien is capable of turning a seemingly inferior squad into a highly effective and unified team. But can they continue to punch so far above their weight? Will their financial limitations catch up with them? Could they reach Europe? Based on the journey so far, I wouldn’t bet against it.

Either way, Clermont Foot’s story deserves higher recognition outside of France, not just as Ligue 1’s ‘other’ underdog, but as yet another example of what a smartly run club can achieve against the odds. Long may it continue.

By: Oliver Haines – @OTG_UK

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / FEP / Icon Sport

Data, Images and Footage: Ligue 1 Uber Eats Official – YouTube.com, Ligue1.com, fbref.com, transfermarkt.co.uk, sofascore.com