Hull City’s Robust Reparation Under Liam Rosenior

One year on from the arrival of owner Acun Ilcali, the Championship league table would suggest that Hull City have made slight but insignificant progress relative to the volume and calibre of signings made in the last two transfer windows, with the club going from hovering ominously above the relegation zone last season to pushing towards the top half this term. However, an enhanced focus on fundamentals throughout the club in recent months has provided much larger growth, which has given hope that there are brighter days to come.

A summer shrouded by exciting signings – some of which proved to be part of an incoherent transfer policy – was reflected by inconsistent performances on the pitch. An encouraging start to the season that brought three straight home wins soon became seven resounding defeats from nine and a lot still to be desired, in performances more so than results.

It almost always takes time to gel a squad full of unfamiliar faces, but efforts to rectify a clear lack of cohesion which led to unforced errors in countless crucial moments were almost non-existent. So, when former Hull player Liam Rosenior came in to replace Shota Arveladze in the dugout last November, there were issues to iron out right through the spine of the squad.

Although the style of play hasn’t changed significantly between the two coaches, there has been a noticeable difference in the manner in which it is executed which is testament to Rosenior’s attentiveness and ability to use his squad correctly. The key principles of the system include a heavy reliance on competent technical ability in the first phase of play. An ability to not only draw the opposition in before acting quickly to exploit the spaces their press exposes, but to adapt proactively in matches by having multiple avenues to play out from.

This makes the patterns of play difficult to predict and therefore increases the likelihood of working the ball out from the back with success, one way or another. That is, of course, the ideal outcome. Something that Hull tend to achieve more often than not these days, which seems like the bare minimum. But, compared to the disastrous start to the season in that respect, they have made enormous progress.

Previously under Arveladze, Jacob Greaves’ ability to pass through the lines and carry the ball up the left wing was Hull’s lifeline to breaking out of the press, and with the team’s obvious limitations in the right channel, teams quickly adapted to drowning them out down the right and causing danger with overturns high up the pitch.

Opposing teams would often mark man-for-man or even press beyond that into the cover shadow to entice passes through tight gaps to prevent Greaves from playing out, whilst leaving right centre-back Tobias Figueiredo with space as the appealing option for Hull. The pass to Figueiredo would then trigger this press, and that is where the problems would stem from, although they weren’t entirely of the Portuguese defender’s own doing.

The reason the former Nottingham Forest man was highlighted by the opposition is partly down to his lack of initiative in carrying the ball and incisiveness in passing forward, but also the misprofiling of those around him. At times, Figueiredo’s options were extremely limited when receiving the ball.

One Player From Each Championship Club Who Will Play in the Premier League – Part One

To his left was Greaves, who has been proven to thrive on the left of a back three or as a left-back in a four, where the channel ahead of him is open and his closest option is a winger or wing-back to combine with. Instead, he was usually confined to the left half-space, occupying left centre-back in a four, where his best options were to pass to a marked full-back or a crowded midfield, both of which were typically quite stagnant or easy to track.

To his right, Figueiredo had a similarly consuming situation to play through, and so for a two-month period, there was a sense of inevitability when facing teams who pressed high that the Tigers would lose possession in their own third at least two or three teams per match, which therefore led to at least one big chance created as a direct result. The following example demonstrates this.

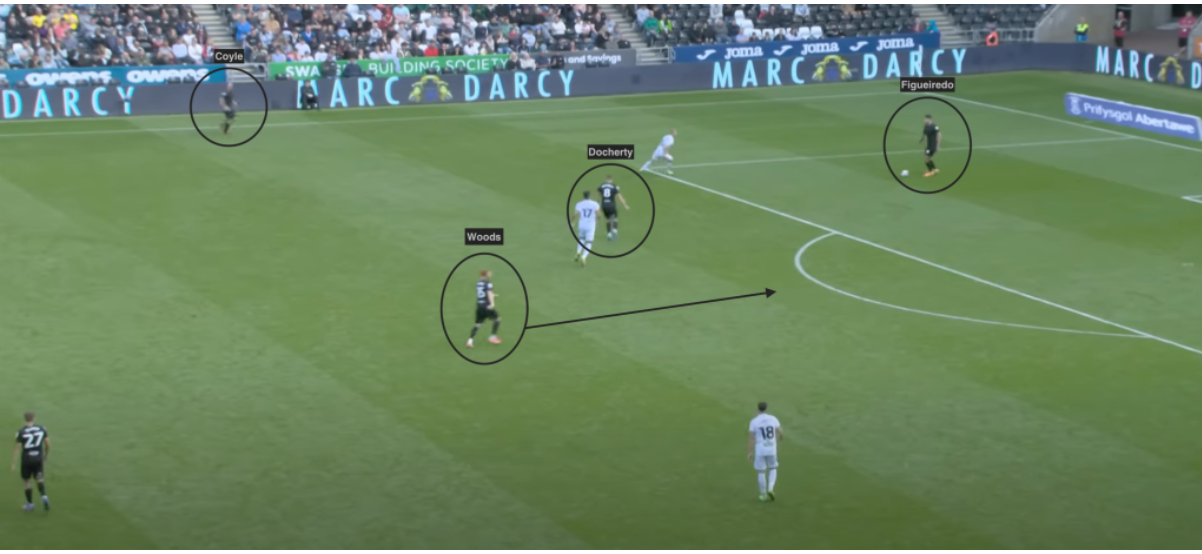

In this instance, the two Swansea attackers attempt to block the passes into Hull’s Lewie Coyle and Greg Docherty, which in theory, should free up space for Ryan Woods to drop in and collect possession with ease, or even receive a lofted pass with plenty of space around him.

However, due to bad positioning from Woods to drop in, and Figueiredo’s slow reaction time to exploit the space and release the ball, what should be a simple pass is played straight to Swansea’s Joel Piroe.

From there, the Dutch striker has a clear run on goal and duly dispatches a chance completely of Hull’s making. When Rosenior arrived, what Hull desperately needed was variety and correctly profiled players across the defence. To suit his style, he needed centre-backs who are composed, quick but not erratic in possession with a good range of passing. Full-backs capable of offering an option to go long or to come inside to give numbers advantage in the centre of the pitch, and hard-working wide midfielders to facilitate this.

Despite not seeming likely with the current crop of players, it quickly became apparent after the World Cup break that, when coached the right way, Rosenior had the right personnel for this to work. His first priority was to free up the right side, and Cyrus Christie soon favoured Lewis Coyle as the more adventurous, threatening right-back option. The calm, dependable Alfie Jones also came in for Figueiredo in the right centre-back spot.

Greaves was shuffled across to compete for left-back with Callum Elder, as Sean McLoughlin offered a similarly reliable, steady presence at left centre-back. The fact that since the World Cup, Hull are one of only two teams, alongside league leaders Burnley, to concede eleven or fewer goals in 16 matches is no coincidence. This is made even more impressive considering that, in the 19 Championship matches prior to Rosenior’s reign, Hull were the only team to concede more than 30 goals, having let in 37.

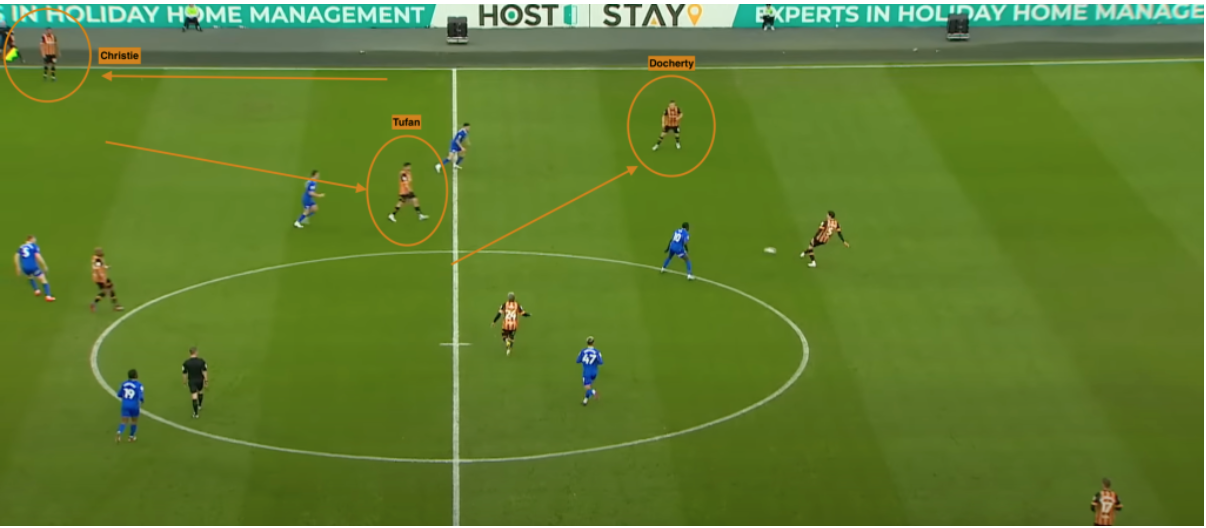

Although the following slides show a slightly different scenario for Hull that isn’t on the edge of their own penalty area, this is still the first phase of play up against a structured Cardiff press, and the options that are available to the right centre-back are much better than the previous example.

By the time Jones receives the ball, Ozan Tufan has dropped inside from the right wing to offer an option and give Cyrus Christie space out wide, which leads to central midfielder Greg Docherty moving to right-back to draw a player out for Tufan to receive possession, and this entices four Cardiff players towards the ball.

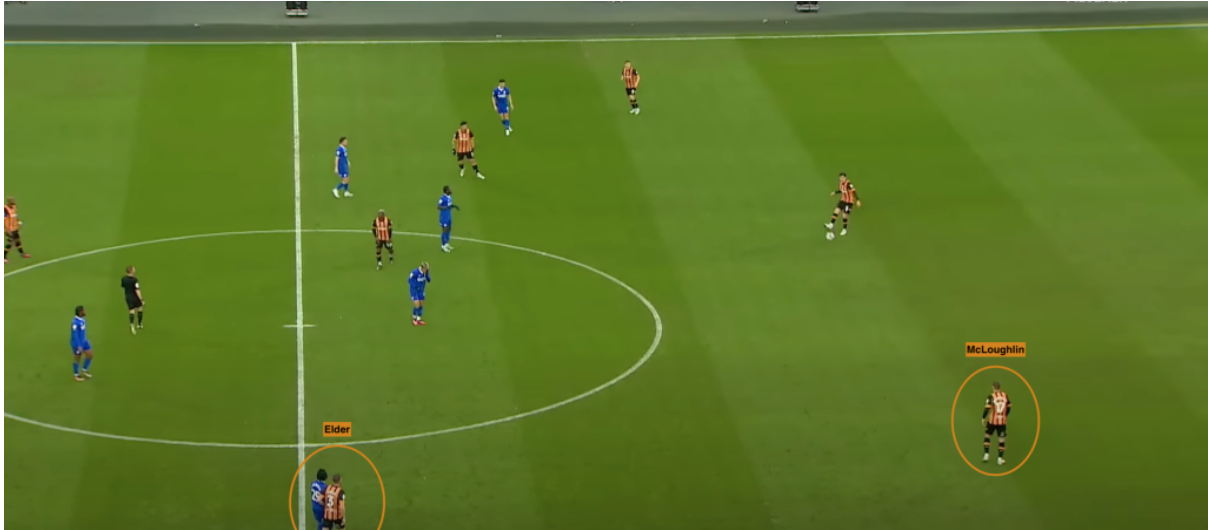

After a quick one-two with Tufan, Alfie Jones opens up the pitch to centre-back partner Sean McLoughlin. By this point, left-back Callum Elder has shuffled into the left half-space to occupy another Cardiff man, which leaves the left-hand side completely open.

From there, a simple pass from McLoughlin finds left midfielder Regan Slater in acres of space to carry the ball forward, thus breaking out of the press with ease. In this instance, Hull’s setup gave them the potential to create a 1v1 down either wing, pushing up Cyrus Christie to essentially become a part of the front three – where he has been instrumental to the team’s chance creation in recent months – whilst providing cover on each side if a loose pass sprung a counter-attack.

This works often for the Tigers because McLoughlin and Jones are both sharp in passing over short distances to adjust their feet and play first time to buy the recipients of their passes a crucial yard in tight areas. With time and space, they are both calculated and quick to assess what is around them and where opposing pressure is coming from, and they have become consistent in picking the right pass to progress possession, helped enormously by the more fluid dynamic in front of them.

In midfield, Rosenior likes to play with a double-pivot of a number six, typically Jean Michael Seri, conducting the play through the second phase, and an energetic number eight alongside him to cover as much ground as possible to give Seri the maximum space and time to work his magic.

Either side of those, he favours midfielders used to playing centrally, who are effective in occupying the opposition’s full-backs by hugging the touchline, or their defensive midfielders by dropping into the half-spaces, which again frees up the team’s creatives – the six and the full-backs by creating a numerical advantage in the respective portions of the pitch.

As a result of these tweaks to the system, recent months have seen Hull surpass the first wave of opposition press far easier, whilst having the players to retreat quickly into a compact low block and nullify any danger of those devastating counterattacks they faced early on in the season.

This focus on diligence and positional awareness across the team has also proved important in suffocating other teams once they reach the penalty area. McLoughlin and Jones are also both competent box defenders, showing patience not to dive in against tricky forwards, dominance aerially and awareness in deciding to pass the ball out or clear long in a split-second when under pressure.

This calm temperament in the penalty area has been infectious throughout a defence that was chaotic in the season’s first half, and because Hull track back so well to gain a numerical advantage, they have become consistently difficult to break down. On Rosenior’s long to-do list left upon Arveladze’s departure, it’s safe to say that Hull’s control of the game in the first two phases deserves a firm tick. However, despite his best efforts, Hull are yet to find their rhythm in the final third under the 38-year-old.

It is an interesting contrast from the top-heavy troubles many fans rightly anticipated following eight attack-minded signings in the summer, but with injuries and inconsistency causing a lack of creativity from midfield, the Tigers have scored just 16 goals in the 15 matches since the World Cup.

The loan signings of Malcolm Ebiowei and Aaron Connolly in January signify Rosenior’s intention to replicate Jacob Greaves’ relationship with the explosive Keane Lewis-Potter out wide from last campaign, where options of a full-back overlap/underlap and Lewis-Potter cutting inside and creating chances from central areas were equally prevalent.

But neither Ebiowei or Connolly are yet to have a sustained impact despite showing glimpses of how this team can work well going forward. Not to mention Allahyar Sayyadmanesh, Benjamin Tetteh, Dimitrios Pelkas and Ryan Longman, who have all endured spells on the sideline. And yet, Hull sit 11 points above the relegation zone following a 1-1 draw at Reading as well as 13 points away from the playoff positions, with the Tigers looking set for a comfortable midtable finish.

A lack of goals has unsurprisingly been met with disdain throughout the fanbase after being promised high-scoring affairs by the club’s owner, and the eagerness to rectify this has and will continue to see the club operate from a much higher standpoint in the transfer market than it did under the previous regime until they get it right.

In finding a manager with a long-term vision and the capacity to fix short-term issues, half of the work has already been done. Rosenior’s philosophy has proved to be effective and, at times, easy on the eye in recent victories. Now, patience, an improvement in the squad’s depth and a bit of luck with injuries are all that stand in the way of a serious push for the playoffs for this team next season.

By: Brad Jones / @bradjonessport

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Gareth Copley / Getty Images