Manuel Pellegrini’s Real Betis: Evolution, Not Revolution

Holder of the highest ever win percentage at four different clubs in LaLiga – Villarreal, Real Madrid, Malaga and now Real Betis – Manuel Pellegrini wears his crowns lightly. With the exception of his time in Madrid, where being thrown out is in fact the norm, the Chilean arguably has hero status at all three of the others.

For a man who has lived through the heat of Santiago de Chile, Buenos Aires and Madrid, each its own brand of pressure cooker, Pellegrini’s demeanour remains demure, his manner stoic.

This latest escapade brings all the baggage of a big club that is often outperformed by both its rivals and its own expectations. The Seville heat is akin to an oven too. Yet without starting a revolution, Pellegrini has casually taken a side from a 16th place finish to third; a miracle without the PR of a younger manager.

Within those thirteen places lie 18 months of continuous work and steady improvement. Still, on a superficial level, this is in many ways the same side that his predecessor Rubi left out of breath and narrowly above the relegation zone.

They play the same formation (4-2-3-1) with a great deal of the same players. The most notable arrival since has been defender Germán Pezzella, a Copa América winner, but also a player Fiorentina parted with for a mere €3.5 million. It’s the only fee that Betis have paid with Pellegrini in charge. Since he arrived, Betis rank 19th in the league for expenditure.

In that same period, Los Verdiblancos have sold €57.8 million worth of talent. Loanees such as Héctor Bellerín and Willian José have come in, while Claudio Bravo, Víctor Ruiz, Martín Montoya, Juan Miranda and Rui Silva were free. The reason being, apart from the latter, all of these players have deemed an insignificant loss to their former clubs.

The team they arrived to was a group of footballers in stagnation. Before Pellegrini, Betis played attacking players without playing attacking football. The ball almost became an enemy as the players struggled to move it. Most opponents simply waited patiently to spring into the space Betis would leave behind.

To return to the present day, Real Betis have just authored arguably the most dominant performance of any team in Spain all season. The ball moves quickly. The players, like Pellegrini, are serious but relaxed. More than any tactical change, the mindset of this group has been reconfigured.

To explain how this translates into the use of the pitch, ostensibly the team revolves around an axis of two left feet, one of which belongs to grizzly warlock Nabil Fekir and the other to Sergio Canales, a smooth magician.

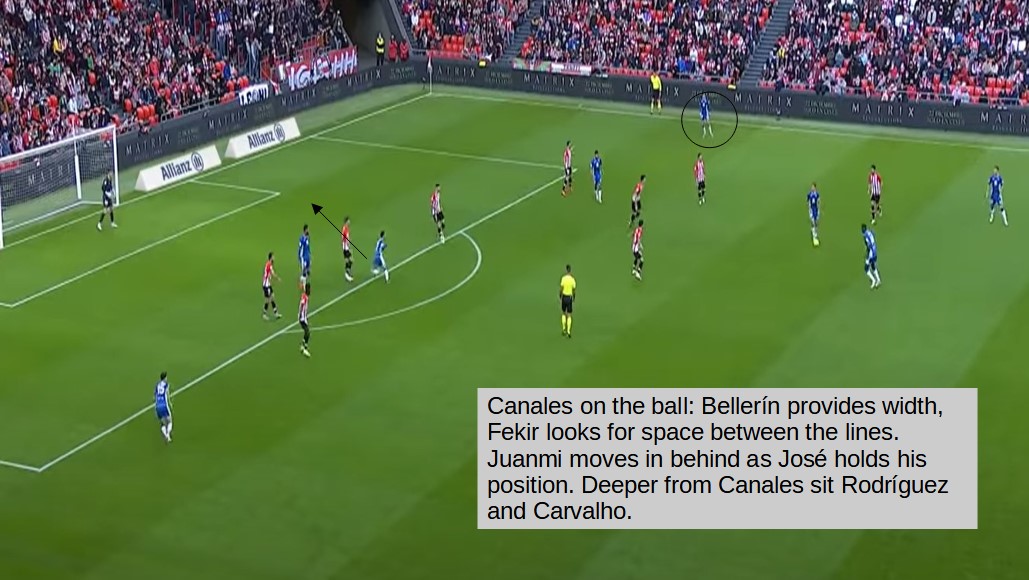

In theory, Fekir occupies the middle of the attacking three, while Canales would be the wide right-hand side of that trident. In reality, the two roam more or less within the width of the box but at different depths. Both are charged with the co-direction of the attack, although Canales will likely receive the ball deeper and often look to find Fekir.

From these two, the rest of the team takes their cue to interpret where they should be. Behind them lurks the security. A capable guard frormed by two of a trio from Mexico captain Andrés Guardado, Premier League rumour William Carvalho and another Copa América winner, Guido Rodríguez.

The latter will usually be charged with short-circuiting counters, while the others must provide an option in the spaces where Canales is not.

Dealing with just four of the XI, the key to Betis’ success with the ball begins to sharpen into focus. Ahead of the defence, the attack is almost always asymmetrical. Many of their superiorities or routes to goal are borne out of this principle.

The role of the central striker is an almost curious one in the context of most football teams. It exists almost more for structural integrity than it does to cause danger. The striker is closest to goal and as such, the place where the goal should come from normally.

Alternating between Borja Iglesias and Willian José, the Spaniard averages just over 32 touches per 90 minutes. They should come short, go in behind, show in the box – play the role of the modern striker. At Betis, it’s almost performative, however.

Within that very conventional role, they exist as a fixed point in the attack. Or more importantly, a fixed point for the defence. This does not mean to say that Iglesias and José are not a key source of goals, but it’s no coincidence that their top scorer with twelve goals is Juanmi.

Don’t Stop Them Now: How Rayo Vallecano’s Feel-Good Tale Has Made a Neighborhood Dream

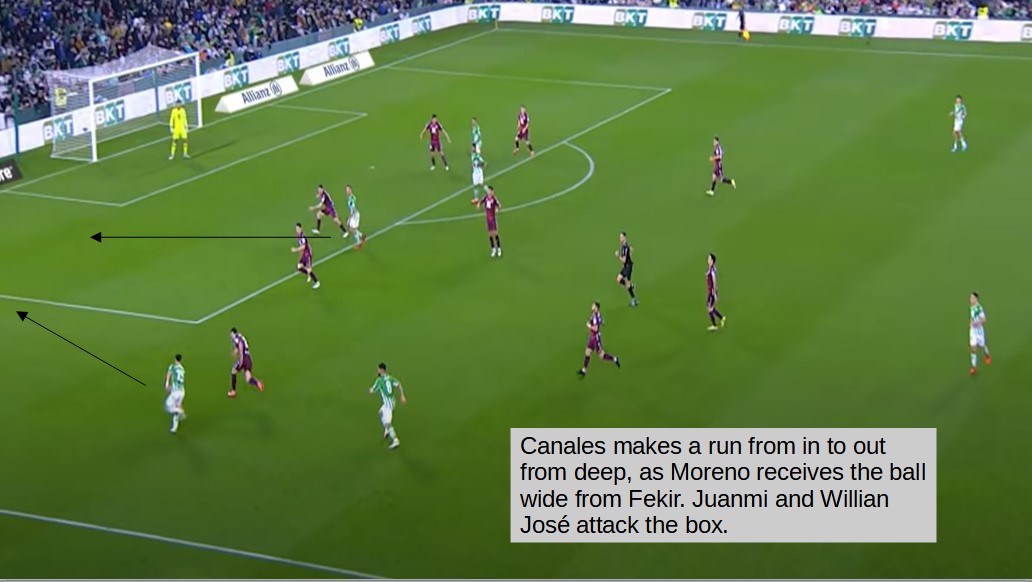

Beginning nominally from the left of the three behind the striker, Juanmi is essentially given the freedom to move inside as he pleases. The trick being that while the number nine fixes the defence, Juanmi is always in motion.

The former Southampton striker has astounded many with his accuracy, outperforming his xG by 4.8 goals. However, the intelligence with which he procures space in the box is just as impressive.

With Fekir and Canales to feed the these runs, it’s proved an almost irrepressible strategy. Second and seventh respectively for key passes, Fekir also leads the league for shot-creating actions.

Pellegrini’s one trademark beyond a general appetite for protagonism would be the full-backs. Even before it became fashionable, Pellegrini has always ensured that the wide areas are a railroad for his full-backs. Usually, that means Bellerín and Álex Moreno and at times, the width of the team is entirely their domain.

Where Pellegrini differs from many of Europe’s genius tacticians is his complete lack of dogmatism. His approach is thin on ego. It’s true that there is a familiarity to each Betis game; ambitious, attractive, ballsy football.

Partly a consequence of the footballers at their disposition, but there is no desire to impose a particular tactic on a match at all costs. The plan is dictated on an objective analysis of strengths and weaknesses.

According to SofaScore, 37.5% of their attacks come down the left side, 37.5% up the right and 25% through the middle. Across the pitch, the ball spends 44% of their games in the middle third and 28% of the time in each of the others. An all but contrived level of balance.

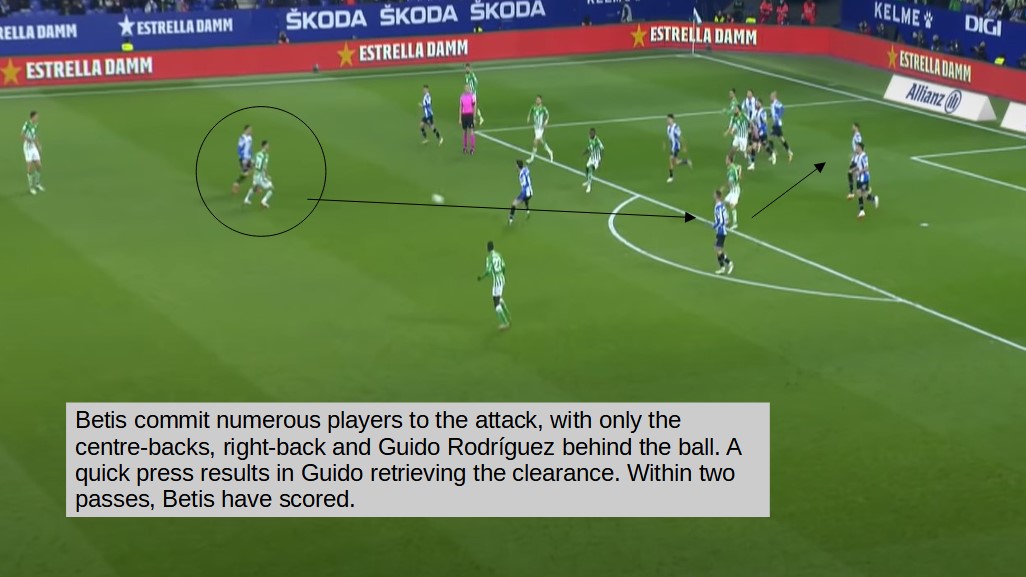

Off the ball, this adaptability comes to the fore. Against Barcelona at Camp Nou, Real Betis played a low block and countered quickly and efficiently down the sides. The final touch arrived on time from the other side, as happened for Juanmi’s winner.

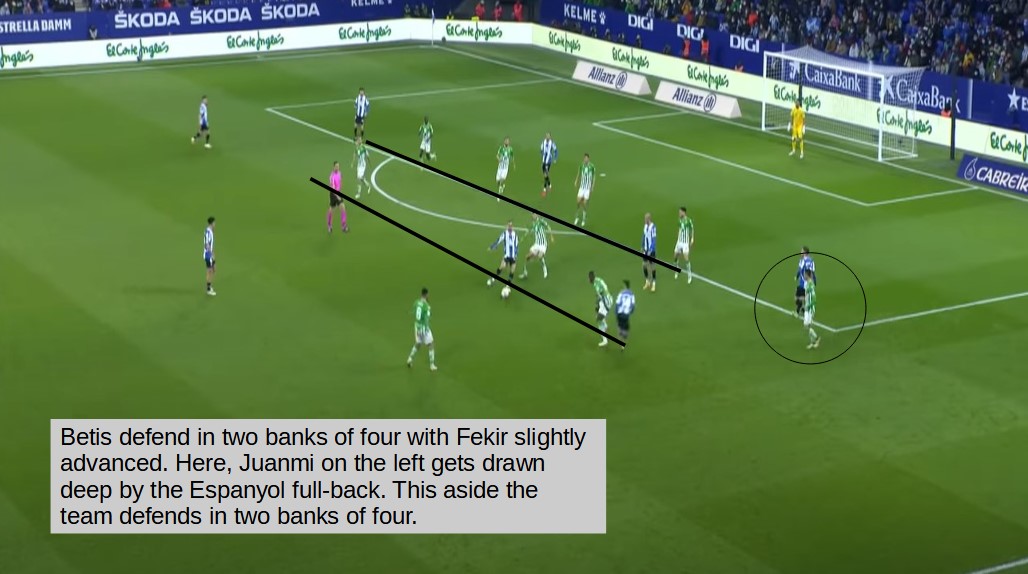

More recently against Espanyol, the press was high and immediate, causing two of their four goals. In most games, the team finally makes sense of the sheet put out before the match by retreating into a 4-2-3-1/4-4-1-1 unit, ten to fifteen yards in front of their area.

Regardless of where or when it happens, it works. Although their poised approach to win the ball back does not jump off the screen, a ferocity and conviction is the key to their defence.

Despite being one of the least defensive teams in the league, Betis deal out the second most tackles per 90 minutes (18.3) after Cádiz. No team in the top half has registered more interceptions per game either.

This commitment has gone a long way to masking the deficiencies within that defence. With Pezzella oft injured so far, La Liga debutant Edgar González has the most minutes in central defence partnered by sometimes suspect veterans Marc Bartra or Víctor Ruiz.

Ahead of them, four of the players are forward-thinkers. Beside them, Moreno and Bellerín have come under fire for defensive lapses previously. Remarkably, none of this has become a major problem so far.

Perhaps it is this emotional intelligence, the ability to avoid being sucked into your own stylistic preferences, which explains Pellegrini’s success. Player performance has been optimised and combined with the cold objectivity to organise the side in the most effective way. Perhaps it explains his 34 years of longevity in management.

The show at the Benito Villamarín seems spontaneous – a bohemian mix of talent working in synchronisation. Yet that’s a product of being afforded creative space.

Without dramatically overhauling the squad nor the style, Pellegrini has tweaked and tailored them into a pretty and effective outfit. “The important thing is the players themselves,” says the 68-year-old. A mantra that remains more sacred to him than any larger tactical ideal of perfection.

By: Ruairidh Barlow / @RuriBarlow

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Fran Santiago – Getty Images