Tactical Analysis: Ralph Hasenhüttl’s Southampton

“If you want guarantees you should buy a washing machine. There are no guarantees in football anymore,” Ralph Hasenhüttl famously stated in his first press conference as Southampton manager on December 6, 2018. In contrast to Hasenhüttl’s parabolic statement, it seems like the biggest guarantee of the Premier League so far this term is the enjoyment and thrill that comes from watching Southampton play.

Born in Graz on August 9, 1967, Hasenhüttl had a relatively subdued playing career, an insinuation the Austrian is happy to confide in when asked about his experience in professional football. A stocky target man in his day, he played for Grazer AK, Austria Wien and Austria Salzburg in his homeland, before moving on to play for Mechelen and Lierse in Belgium.

He finished his career playing in Germany for FC Köln and Gruether Fürth before playing his last games in Bavaria for Bayern Munich II in the Regionalliga Süd, where he would brush shoulders with Philipp Lahm, Bastian Schweinsteiger and Paolo Guerrero in their teenage years. Following his retirement, he headed to the outskirts of Munich where he served as a youth coach at SpVgg Unterhaching.

After two fruitful experiences in the third division with SpVgg Unterhaching and VfR Aalen, the 46-year-old Hasenhüttl took the reins of FC Ingolstadt 04, replacing the departing Marco Kurz in October 2013. In his first season, Hasenhüttl took them from last place in 2. Bundesliga to a respectable 10th-place finish. The following season, Die Schanzer won promotion to the top flight for the first time in club history, finishing atop the league table with 64 points from 34 matches.

Photo: EPA/ Marius Becker

After managing an impressive 11th-place finish in Ingolstadt’s inaugural season in the Bundesliga, Hasenhüttl decided it was time for a new challenge. He left Bavaria and headed to Saxony, where he would take charge of newly promoted RB Leipzig. Bolstered by a treasure trove of young talents such as Naby Keïta and Timo Werner, Leipzig finished second in the Bundesliga, although they failed to regain the same magic in 2017/18 and finished sixth.

Shortly after the season’s completion, it was revealed that wunderkind manager Julian Nagelsmann would leave his post as Hoffenheim manager and take over as Leipzig manager at the end of the 2018/19 campaign. Unwilling to be a lame duck, Hasenhüttl asked for his contract to be terminated, but he didn’t have to wait long for his next opportunity to arrive at his doorstep.

With Southampton embroiled in a relegation battle, Hasenhüttl replaced the widely unpopular Mark Hughes and managed impressive victories over Arsenal, Tottenham and Wolves as Saints narrowly avoided the drop. They comfortably avoided relegation the following year, finishing 11th in the table, and today, they find themselves 4th in the league after taking points from the likes of Chelsea, Everton and Aston Villa.

Tactical Set-Up

Hasenhüttl organises Saints in a 4-2-2-2 formation, a variant of the more traditional 4-4-2, although it reverts back to the 4-4-2 when out of possession. The main difference from the traditional 4-4-2 is that the wider midfielders, usually Stuart Armstrong and one of Nathan Redmond or Moussa Djenepo, tend to operate in and around the half spaces rather than staying high and wide, especially when in possession. This in turn allows the full-backs Ryan Bertrand and summer acquisition Kyle Walker-Peters to push forward and constantly offer width.

The strike partnership of Danny Ings and Ché Adams has been a fruitful one, having combined for 9 goals so far this term as well as four assists. However, Adams and Ings’ relentless work rate is just as impressive, with the duo setting the tempo to initiate Southampton’s aggressive pressing strategy, offering high-octane energy as well as situational intelligence to be aware of various pressing triggers.

A midfield two combination is becoming more uncommon with teams favouring midfield superiority with a three-man central midfield. In this system, James Ward-Prowse operates as a box-to-box midfielder, with Oriol Romeu deployed as a six and the destroyer in the middle of the park.

At the heart of the defence, Jan Bednarek, a typically no-nonsense centre-half, partners a more progressive passer in Jannik Vestergaard, the Danish defender having amassed 25 passes into the final third already this season. Alex McCarthy has been a mainstay in the Southampton team and despite being on the wrong side of 30, he has adapted his game to become more of a sweeper-keeper, a necessary role behind a back-line that operates high-up the pitch.

Defensive Organisation

Arguably the biggest improvement from Southampton since Hasenhüttl’s arrival in 2018 has been the way the team has defended. A common German term in modern football is ‘Gegenpressing,’ or counter-pressing, and Hasenhüttl is a major proponent of this ploy which seeks to win the ball back close to the opponent’s goal by fiercely closing down the opposition.

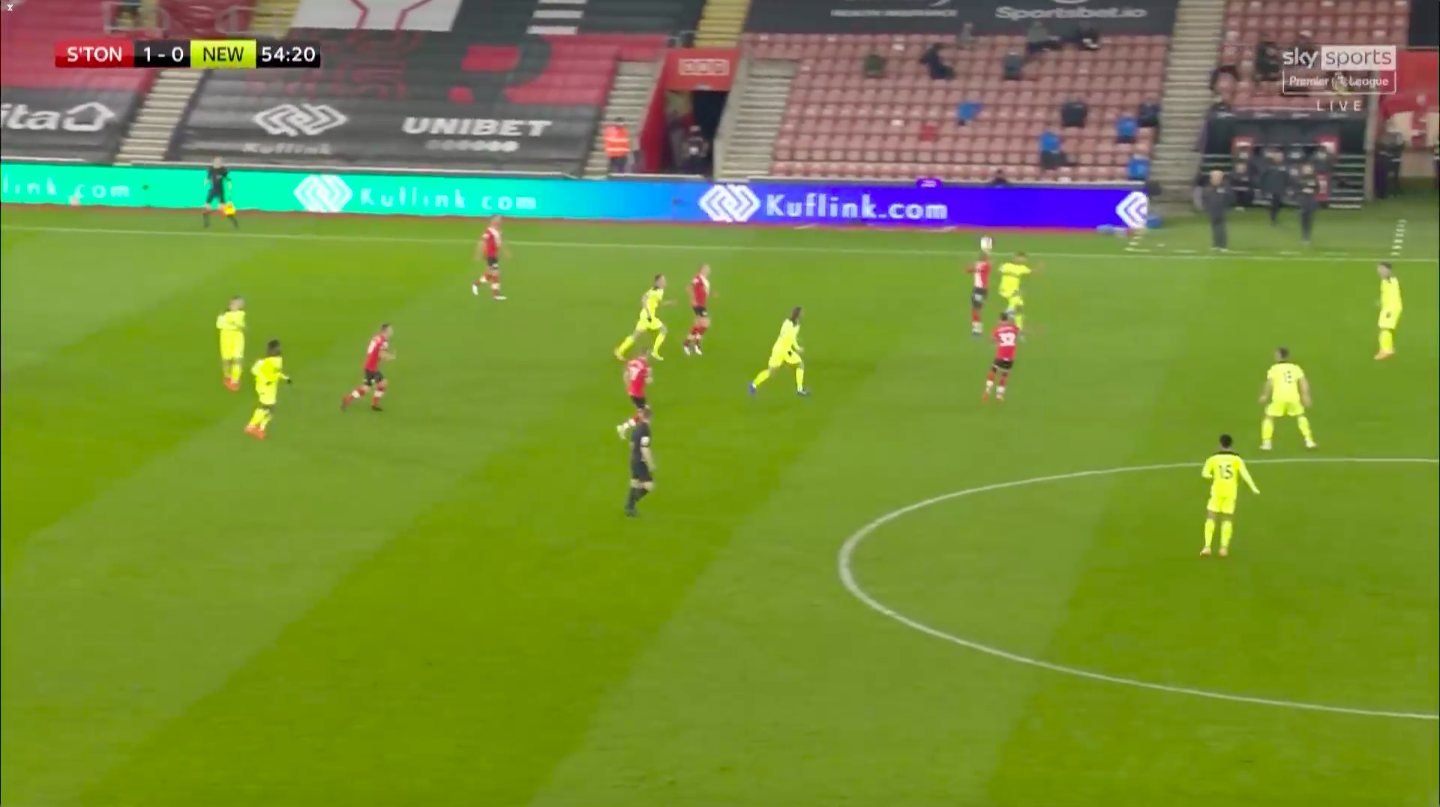

In order to properly execute the Gegenpressing, Southampton press incredibly high up the pitch in an attempt to retain numerical superiority in advanced positions and win back the ball from the opposing player in prime goalscoring areas. We can see an example of this in the previous match against Newcastle; after Karl Darlow palms away a powerful shot from Ings, Miguel Almirón comes to collect the ball, but he’s followed in hot pursuit by Walker-Peters.

Almirón could have and should have dished it off to Jeff Hendrick, but he instead attempts a fanciful pirouette to evade both Walker-Peters and the ensuing Theo Walcott, landing himself in even hotter water. Walker-Peters pokes the ball away and into the path of Walcott, who dribbles into the box before firing a pass towards Adams, who fires in the opening goal.

Any team can go out and press, but few do it efficiently. Hasenhüttl has instilled more defensive intelligence by drilling home various pressing triggers. As shown above, the body shape of the opposition player receiving the ball denotes whether a press can be initiated. Walker-Peters realizes that after receiving with his back to his opponents (and teammates), Almirón is in an extremely vulnerable and error-prone position.

There are several indicators that tell Southampton players whether or not to initiate the counter-press, be that the accuracy of the pass or the positioning of the receiving player, and Hasenhüttl drills his players with the mission of preventing the opposing team from reaching their most creative players with the ball as well as regaining possession in dangerous areas.

One noticeable factor from Southampton press is Hasenhüttl’s desire for his forwards to dictate the play of the opposition. Depending on which centre-half has the ball, one of Adams or Ings or Walcott applies pressure to the centre half in order to prevent the ball from coming in field, and the surrounding players apply pressure to funnel the ball to the opposition full-back.

As a result, one of the wide midfielders is able to press the player whilst using the touchline as another defender. In doing so, Southampton can force the opposing players into attempting errant passes and turning the ball over or passing it backwards to the center backs and/or goalkeeper.

Despite often being expansive when defending from the front, Southampton have shown that once the initial line of engagement has been broken, they can remain compact in a mid-block, cutting the supply line to the final third in an attempt to dictate the play into wider areas before using the touchline as an extra defender to close down the opponent.

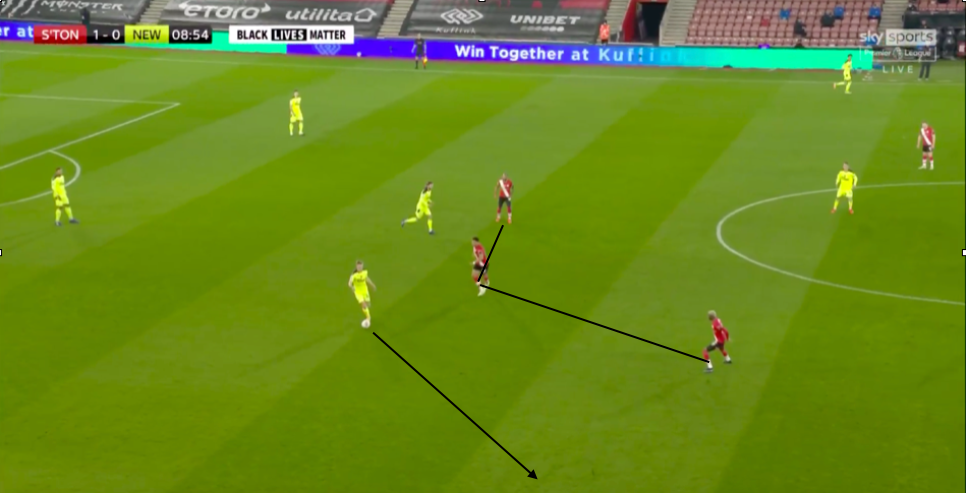

The majority of Premier League sides favor a three-man midfield, such as Liverpool, Manchester City and Everton, enabling them to outnumber Southampton in the middle of the pitch. In order to counteract this, Hasenhüttl commands his wide midfielders to invert their positioning and suffocate the opposition, with the aim of retaining the ball and recycling it either to the centre halves to start the attack from deep, or to one of the full-backs who can then exploit the vacated space.

The below example shows how Southampton’s narrow positioning can allow them to form a box and encompass the opponent, with Walcott, Djenepo, Romeu, Armstrong, Jack Stephens, and Ward-Prowse surrounding three Newcastle players. If Djenepo beats Jacob Murphy in the aerial duel, Southampton can then launch a counter-attack.

Building the Attack

As impressive as Southampton’s turnaround in their defensive solidity has been, Hasenhüttl has also overseen a dramatic improvement in the team’s attacking phase, especially after ditching the 5-3-2 that he used in the beginning of his time in the South Coast and reverting to his tried and trusted 4-2-2-2.

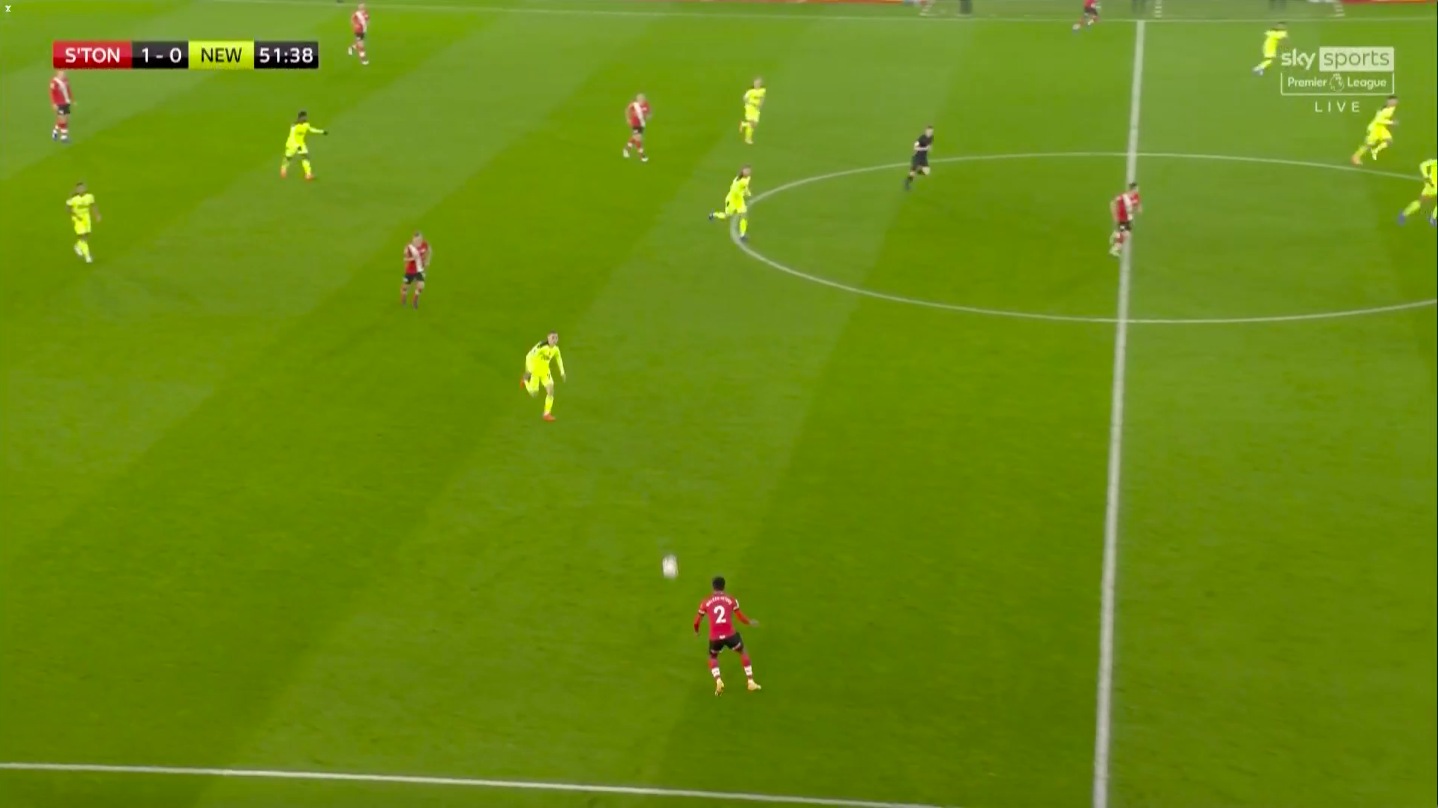

Southampton have started building their attacks from deep with an emphasis on dominating possession, and a big reason for this has been Vestergaard, who displaced Stephens in the starting line-up after a 5-2 loss to Tottenham on September 20. The 6’6″ Dane has the ability to progress the ball into midfield or into advanced positions by playing diagonal balls towards the fullbacks, allowing Southampton to beat the initial line of press and take the opposing players out of the game.

Higher up the pitch, Hasenhüttl demands his players to operate in the ‘Red Zone,’ the area in front of the opposing defense, as the conglomeration of Saints players in the hole can leave opponents in a Catch-22 where they’re forced to either pressure the player on the ball or drop even deeper and providing the Saints player with even more space to exploit.

So far this season, Ings, Armstrong and one of Djenepo or Redmond will typically roam the ‘Red Zone,’ although Walcott will be replacing Ings in this facet for the following month due to the latter’s knee injury in a 4-3 victory against Aston Villa. In the below example, Walcott operates in the hole alongside Armstrong, who vacates the flank to seek a pass behind Newcastle’s midfield line.

Having a numerical superiority in this zone allows the players to weave together intricate passes behind the defensive line for sharp players such as Adams to latch onto, a quality that Armstrong offers. Alternatively, the wider midfield players drop into deeper spaces to receive the ball and penetrate into the red zone through a dribble as opposed to a pass.

Southampton’s capture of Walcott on a season-long loan from Everton is crucial for this. Like Djenepo, the 31-year-old English forward has the requisite pace, dribbling ability and directness to be able to penetrate into the ‘Red Zone’ with the ball at feet. Nearly 15 years after leaving his boyhood club for Arsenal, Walcott is proving that he still has the ability to make a difference at the top level.

Conclusion

Less than two years after taking charge of the South Coast club, Hasenhüttl has taken Southampton from a relegation battle to a battle for European football; in fact, they briefly led the Premier League for the first time since 1988 (when it was still known as the First Division) after their 2-0 victory over Newcastle. Moreover, as Mohammed Salisu and Ibrahima Diallo adjust to the Premier League and near full fitness, Hasenhüttl will have even more options at his disposal in the crowded holiday period.

Hasenhüttl’s demanding training regime has allowed Southampton players to meet the physical demands that come with executing his self-proclaimed ‘demanding’ style. His tactical nous has also returned the feel-good factor back to the south-coast not seen since the days of Ronald Koeman, and whilst Southampton will almost certainly drop out of the race for top four due to their relative lack of depth, Saints fans can look forward to even more improvement and progression under the watchful eye of their Austrian tactician.

By: Russell Pope

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Matt Watson / Southampton FC