Tactical Analysis: Stefano Pioli’s Milan

After a disastrous start to the 2019/20 season, Marco Giampaolo was sacked from his position as Milan manager. The Rossoneri had picked up just nine points from the first seven league matches of the season and were sitting in 13th place, trailing league leaders and eventual champions Juventus by 10 points. The Milan leadership made the decision to fire Giampaolo and bring in Stefano Pioli as manager.

Pioli’s original contract was set to expire at the end of the season, and the general idea was that Ralf Rangnick would then assume the position the following summer. However, after a 10-game unbeaten run which saw them defeat league leaders Juventus and title challengers Lazio, Pioli was rewarded with a 2-year contract. This article will investigate the tactical aspects of Pioli’s Milan to find out why Milan abandoned their pursuit of Rangnick and instead bought into their Italian tactician.

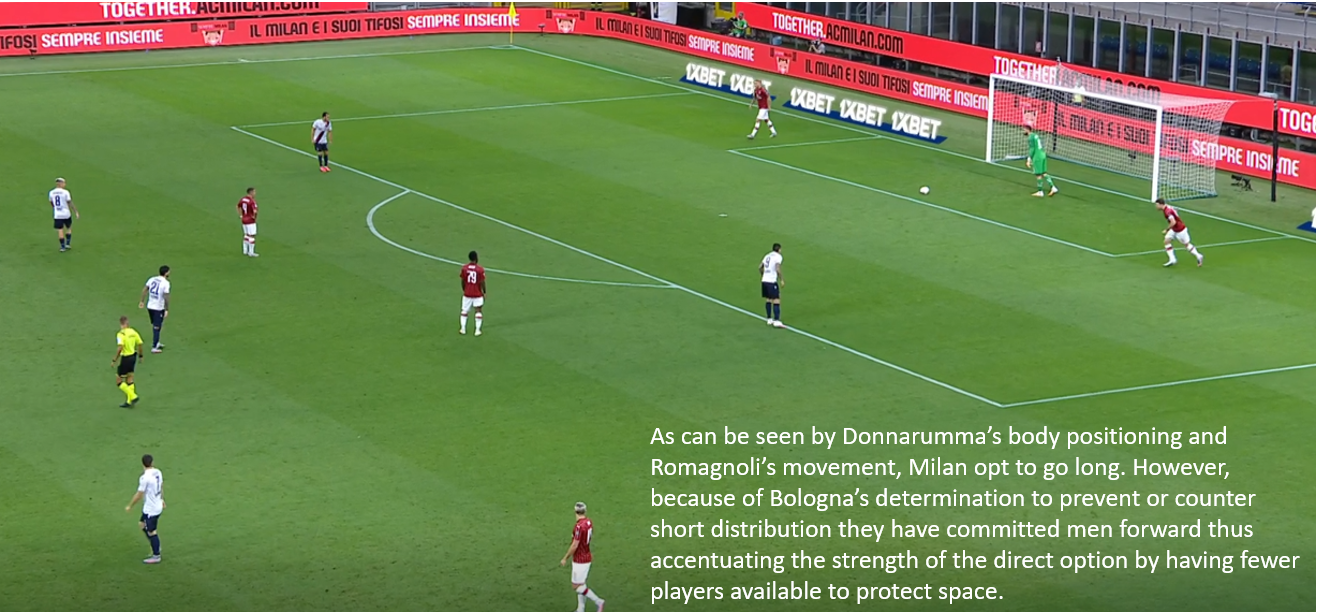

During the build-up of possession, Milan are versatile in that they can go direct because of Zlatan Ibrahimović’s aerial prowess while still possessing enough individual quality to play out of defence thanks to players such as Alessio Romagnoli and Ismaël Bennacer. Should Milan drop their centre backs deep parallel to goalkeeper Gianluigi Donnarumma, they strengthen the direct option by making it more difficult for the opponent to remain compact through making the playing area bigger.

This forces the opposing team to commit more resources forward and thus have fewer players nearby to compete for potential second balls or to react to Milan consolidating possession in advanced areas. As such, they can compound their potential gains from a header won given the fact that there is more space for the opposition’s defense to cover.

Conversely, the option of Ibrahimović and cognisance of the aforementioned interplay could potentially cause the opponent sit back and attempt to congest central areas where Ibrahimović’s header could fall. This then allows Milan’s defenders and midfielders to advance relatively unperturbed and gain territory, allowing them to sustain pressure which would have been more difficult without having the direct option of Ibrahimović to deter a high press.

The option of Ibrahimović as an outlet therefore creates a positive feedback loop as the better Milan become at going direct, the better they become at playing out of defence and vice versa with their adaptability, allowing them to tailor approaches to opponents better rather than being constrained to a disadvantageous approach due to a lack of options.

Against proficient pressing sides, they can go direct whereas against defensive teams they can more safely build progressively through the defence.

When going long, Ibrahimović typically drops deeper rather than attempting to force the defending team backwards and attempt a flick on in behind. This has two possible explanations: firstly, Milan lack pace in attack with none of their regular starters being renowned for their ability to get in behind, so instead of seeking to create direct from going long, the preferable option would be to tailor their attacks to their players through attempting to consolidate possession in more advanced regions to subsequently work the ball forward, as they prefer to have the ball played into their feet.

The second motivator is either to create a situation where Ibrahimović is more likely to win a header by placing himself against a midfielder who is typically smaller than a centre back thus taking advantage of a clear qualitative superiority, similar to Mario Mandžukić under Massimiliano Allegri.

This tendency from Ibrahimović could lead to a centre back being aggressive and following him, thereby allowing Milan to draw a centre back out of position to contest the header, thereby disrupting their defensive shape and putting them in a worse position should Ibrahimović win the header.

When Milan do seek to build from the back, Bennacer typically drops back to provide a central passing option after the centre backs have split in order to provide a numerical superiority against the first wave of pressure. They subsequently look to move forward in a low risk manner, circulating between the defensive six players against teams that do not press their centre backs.

They aim to gain territory and enable their fullbacks to receive the ball in advanced positions once they begin transitioning towards the attack. When under pressure from the opposition, Milan are more inclined to distribute directly to the full back.

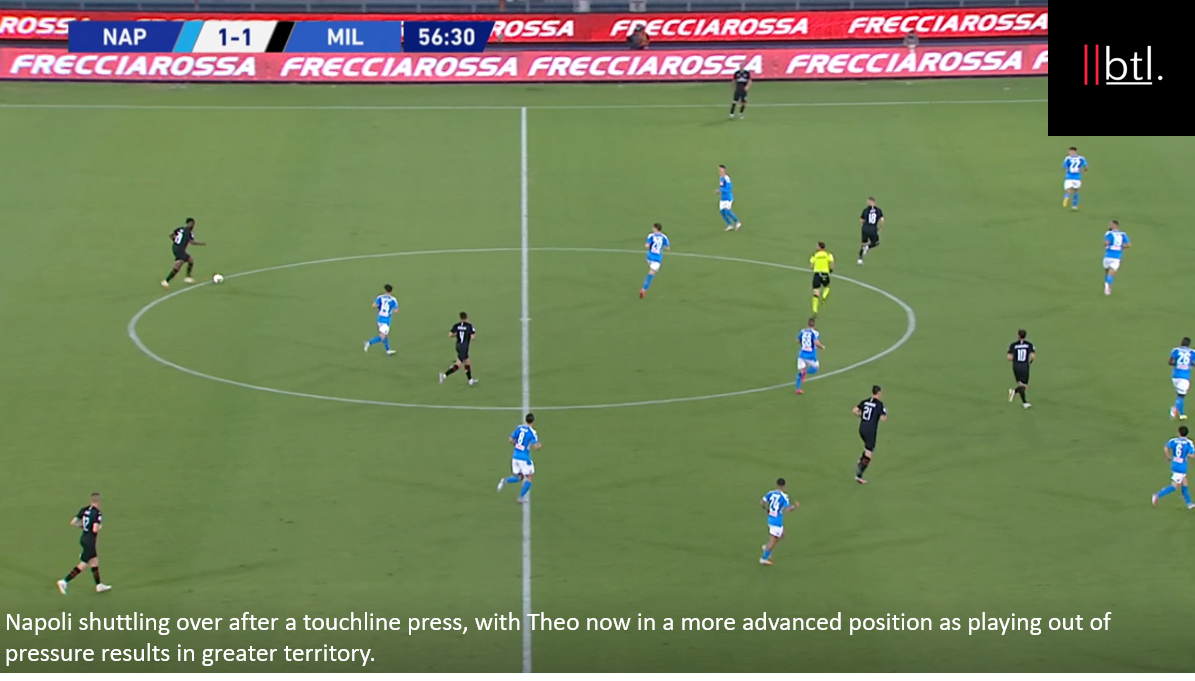

Milan disproportionately build up possession on the right flank for two reasons. Firstly, Bennacer can better circulate possession and exploit space via passing than Franck Kessié, who plays on the left side of the double pivot. Secondly, this creates space for left back Theo Hernandez, the more adventurous of the two fullbacks, through forcing the opposing defence to shuttle across and protect the ball-side.

This type of build-up allows for short, quick combinations between the midfielders and wide players who can subsequently exploit the space gained through bypassing the opposing touchline press. They have subverted a cliché often associated with compactness, as narrow build-up allows for Milan to achieve passing combinations against high pressing sides. Milan seek to contract initially so that when the expansion does happen, the player on the opposite flank has more space to exploit.

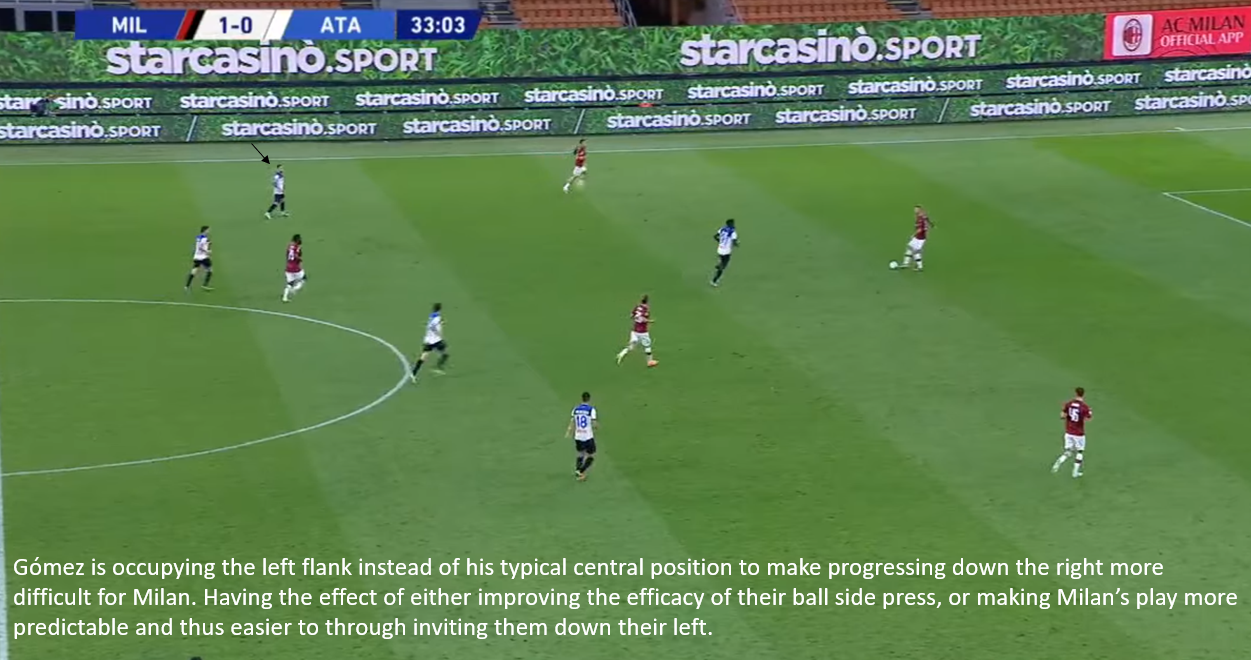

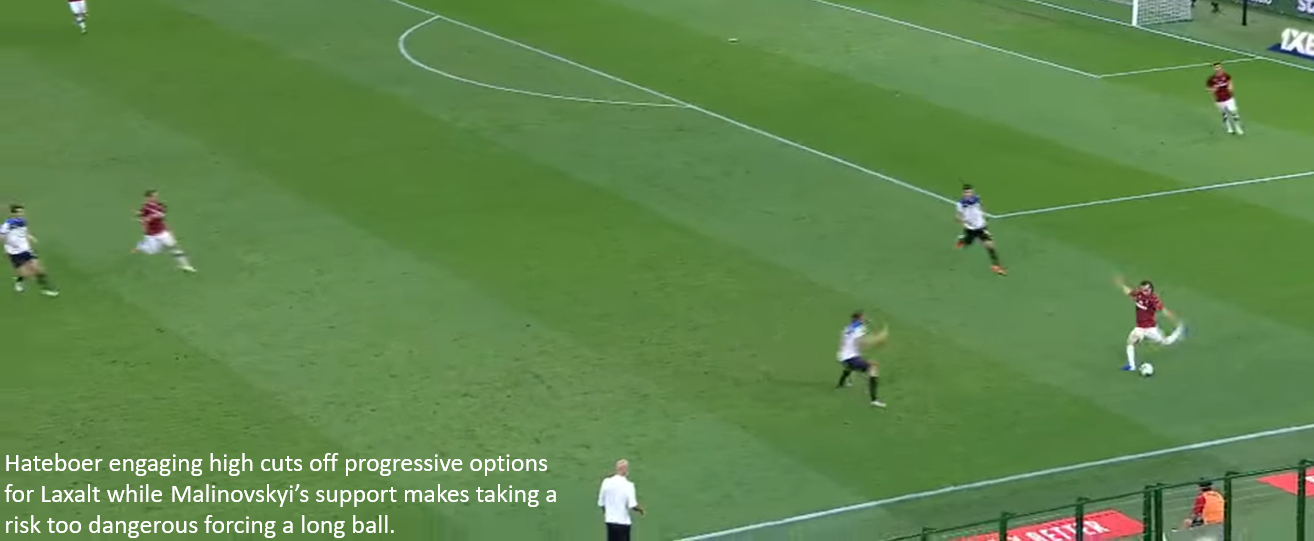

Atalanta adapted interestingly to this tendency of Milan’s by moving Alejandro ‘Papu’ Gómez from his more central position out on the left. This allowed him to pressure Davide Calabria more easily which limited what Milan could do by forcing play down Milan’s left side, where Hans Hateboer could press high under the knowledge that this was Milan’s only route of progression.

This highlighted an issue in the wide build-up: their ability to be counteracted by asymmetric commitment in combination with the high full back/ wing back commitment. By committing disproportionately to Milan’s favoured build-up side, the opponent either increases the likelihood of Milan struggling down that flank or forcing them to focus down the left, thus allowing Atalanta to prepare accordingly and forcing Milan to be less comfortable in their approach.

However, Atalanta are a unique side and thus should not be perceived as being representative overall, as their narrow shape combined with their high pressing and the presence of wing backs who naturally have greater cover and can engage higher with greater security made them ideal for targeting wide build-up. Additionally, this was potentially the worst match to go without Hernandez, who through his dynamism could have more reliably beaten his man in a 1 vs 1 deep match-up.

Nonetheless, their attack can be easily stifled when the opponent can effectively engage out wide with full backs while engaging in a touchline press to limit central passing options. But even without effective infiltration between the lines, they could still rely on Ibrahimović who could provide layoffs to players between the lines.

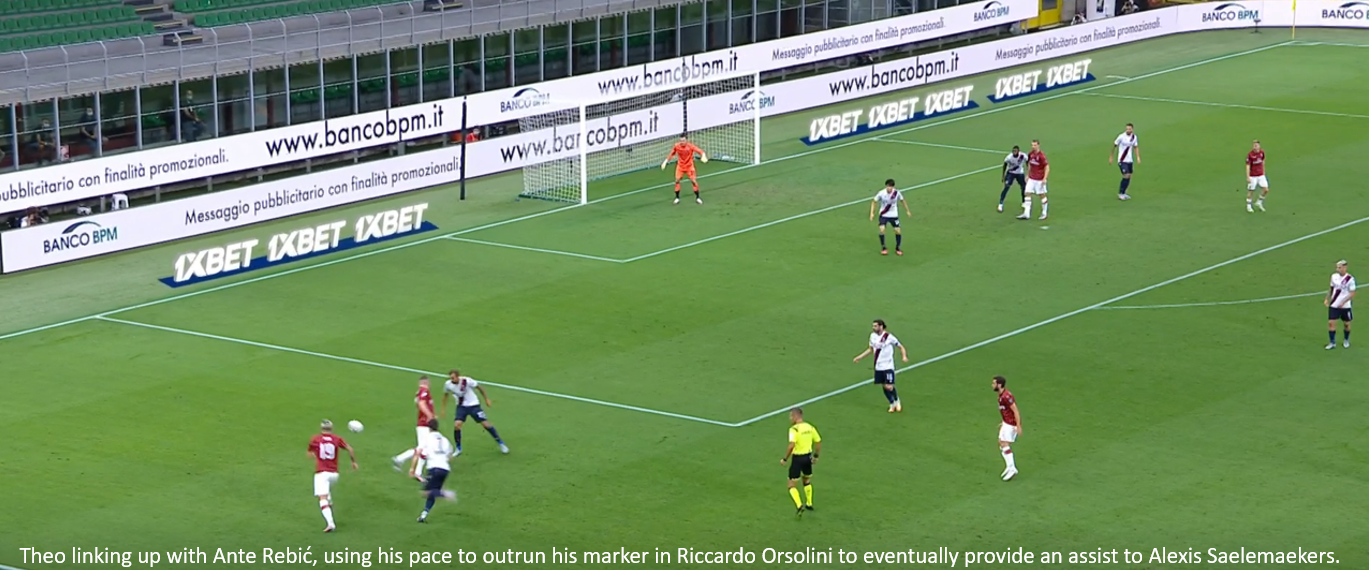

In attack, significant emphasis is placed upon the role of Hernandez to exploit his explosive pace to overload defences with his marauding runs to play either a cross if he overlaps, or a pass, shot or a drilled cross if he decides to underlap. His dynamism is a tool that Pioli has employed to great effect by allowing him the freedom to roam.

Hernandez’s deeper positioning makes his runs more difficult to track as he is rarely static when Milan are transitioning, thus increasingly the likelihood that he is free between the lines, especially if the opposing full back is occupied with Ante Rebić. He always has the initiative when charging into space, meaning he has a head start and often the physical advantage over his marker.

Dealing with Hernandez zonally is rather difficult because of the emphasis most teams place on protecting central zones, with the externalities of committing more players towards Hernandez’s zones outweighing the advantages gained, as now Milan’s route of penetration becomes central rather than wide which is generally more dangerous.

A centre midfielder or defender can support a defence in wide areas to make it less oriented around individual duels, but that movement is often lateral, thus making the timing of an interception difficult and forcing them to commit to defending in wide regions. In essence, once he is in his stride, he is difficult to stop thanks to his sheer physical power, speed and ability to exploit open spaces.

Another potential solution could be doubling up on Hernandez during build-up or pressing aggressively to prevent forward movement and/or to make playing the overlapping pass difficult for Rebić, which is difficult because of his strong frame, thus making him suitable for hold-up play.

Ultimately, one can never cancel one disadvantage without another one arising, and Hernandez’s physicality and positioning make it difficult to stop him to the extent where the new created disadvantage is even greater.

His forward orientation and direct style of play make him extremely difficult to defend against and therefore when he is executing on the ball actions well, something which he has done for the majority of the season, a reliable chance creation mechanism.

Hernandez’s unpredictable approach makes a laissez-faire style of tactical management towards him prudent, as he has the power to inject chaos into a structured opposing defence, unsettling them and forcing adaptations. Scoring six goals and assisting three this Serie A season, he has been a crucial member of Milan’s attacking set-up.

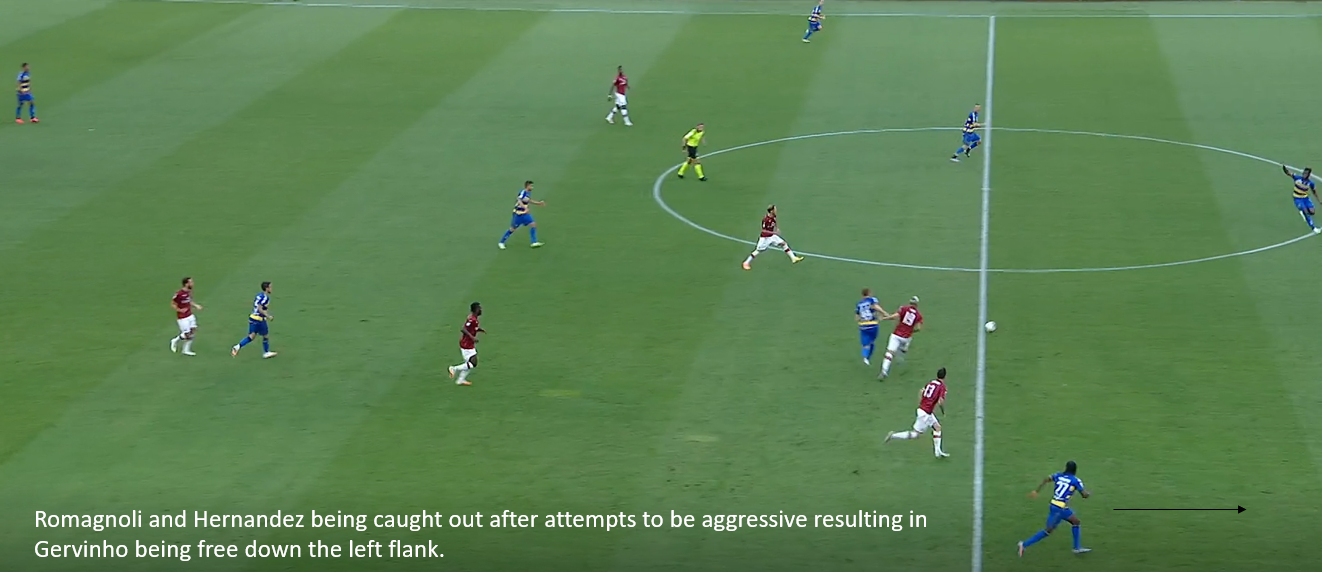

Accordingly, Milan tend to press with greater intensity down the left flank as the greater commitment offensively subsequently requires a greater commitment from the counter press to prevent the opponent from working the ball into the space exposed.

Milan’s pressing efforts more generally are limited, as the 38-year-old Ibrahimović simply does not have the energy to maintain intense pressing for 90 minutes anymore. Despite this, they still engage relatively high while pushing their midfield forward to support efforts in an attempt to control territory.

They seek to disrupt play once the opposing team has transitioned or are looking to transition past their first line, which in essence means they do not press the opponents centre backs with intensity, although they do lightly to force decisions.

As such, the first engagements often occur in defensive midfield or with the opposing full backs. This style is oriented around attempting to force the opponent to play down the flanks by congesting the defensive midfield zone where they can subsequently engage in a touchline press.

Space in between the lines is an issue at present for Milan when defending high because they need Kessié and Bennacer to move forward in orderto support the attempt to sustain pressure, meaning the space that double pivot would typically occupy will remain undefended, provided the opponent can find a line-breaking pass.

Milan’s centre backs and fullbacks often aggressively press the player who receives the ball in between the line in an attempt to force possession backwards or regain possession through either a misplaced pass due to the pressure or a tackle. This can lead to space arising in behind if the defenders lose their initial duels, but it is still the best way to cover for the gap in between the defence and midfield rather than allowing the opponent to gain territory unperturbed.

The aim of Milan’s high engagements therefore is to prevent the opponent from comfortably building in deep central areas, and instead forcing them to play through the full backs or play direct where they subsequently increase the intensity of the pressing.

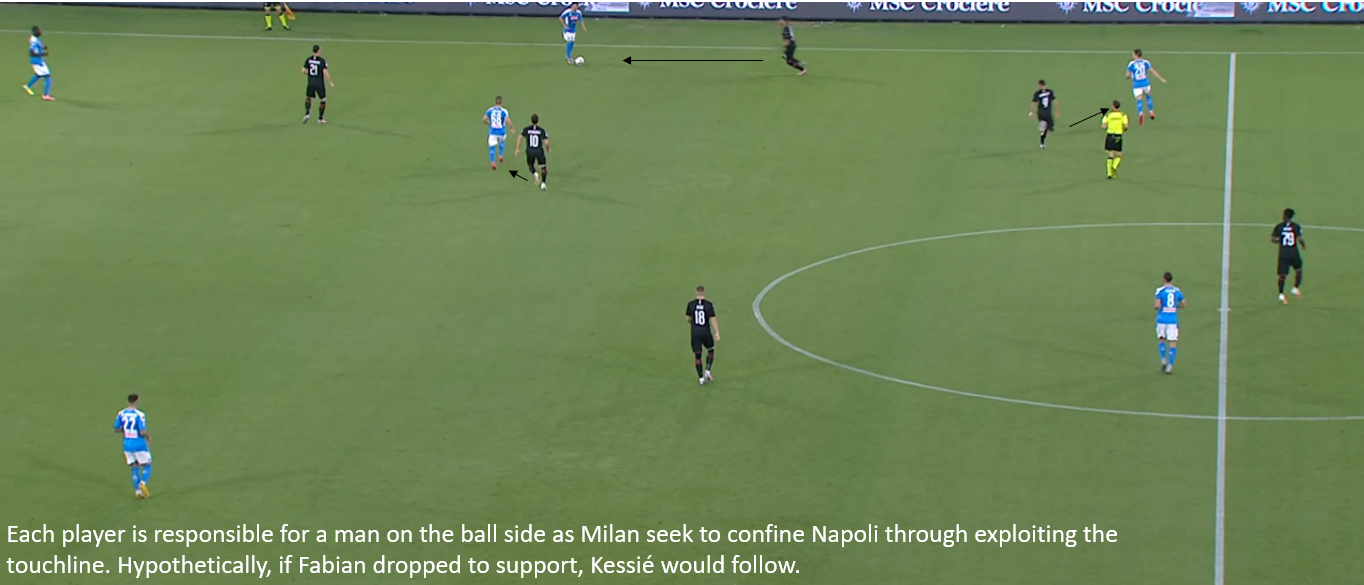

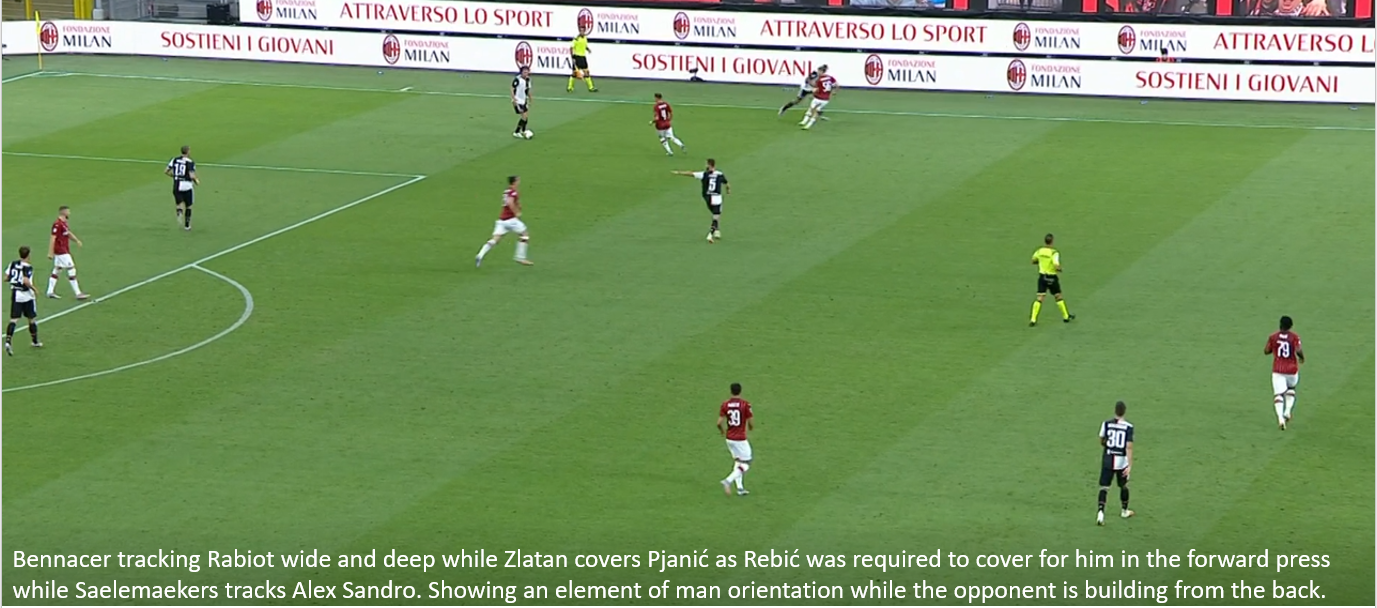

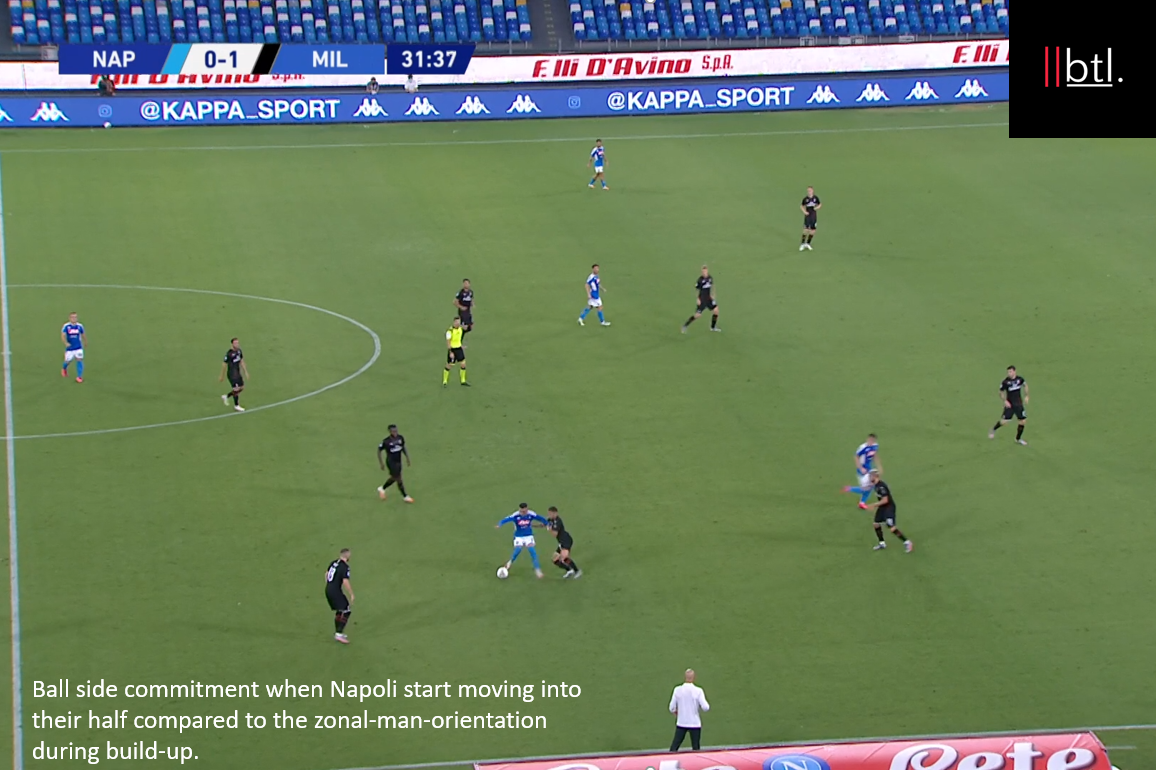

The issue of space protection in midfield is a recurring theme because Milan play a man oriented midfield on the side of the pitch they are pressing, seeking to pressure the opponent that receives the ball to feet therefore allowing them to sustain pressure.

However, when the opponent builds in a compact manner (such as Sassuolo in the example above), this can lead to huge gaps of space being available which provided they can bypass the pressure which can lead to numerically disadvantageous situations defensively.

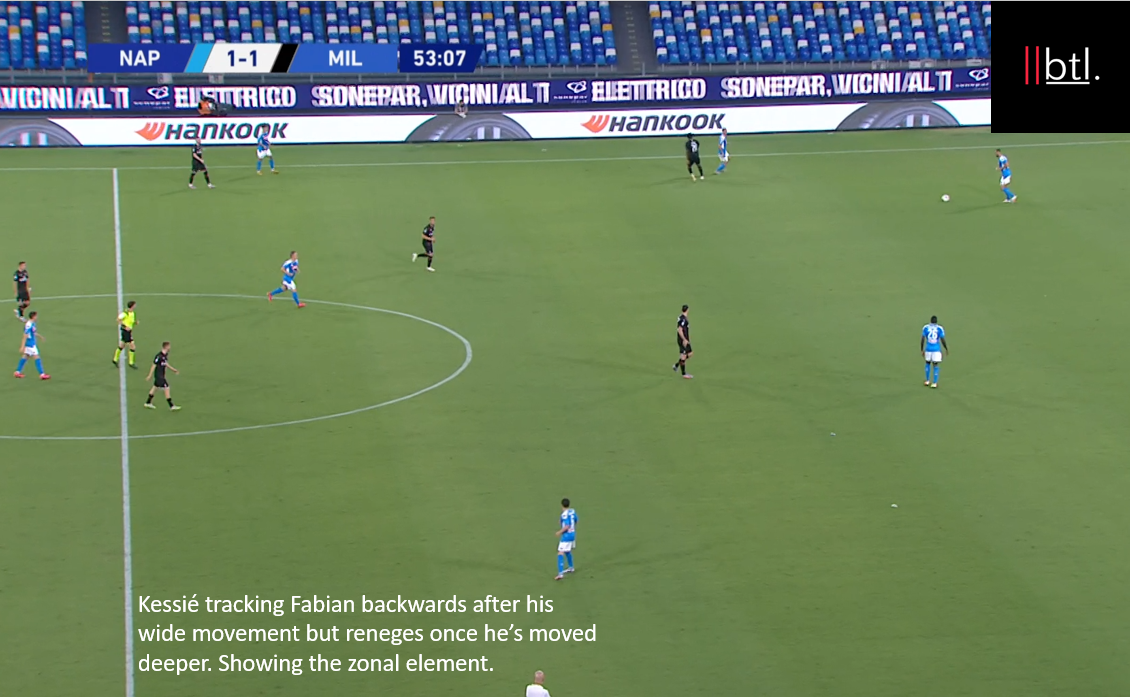

It is important to note however, this is man-oriented pressing rather than man-oriented marking seen at Atalanta or Hellas Verona. The players largely remain zonal, but when triggered through the ball shifting over to their side of the pitch, or their man looking to receive possession in unconventional areas, they will follow to an extent and subsequently press.

Perhaps more accurately, Pioli employs zonal-man system, whereby responsibilities are dictated by the positioning of the ball, much like a zonal system, and each player is given a designated zone to protect but there is a greater commitment towards overloading the ball side out of possession to confine the opponent by limiting passing options and reducing the size of the pitch.

Their approach off the ball against most sides when the opponent is transitioning into attack is predicated on congesting central areas when high, using the touchline to confine the opponent as their passing options become more limited.

As such, in order to cover for the space left exposed by the press, Milan aggressively hassle the player in possession, marking tightly and pressing in a man-oriented manner while their positioning and commitment moves in accordance with the ball.

Ultimately however, attempting to codify how this Milan side defends is difficult because of Pioli’s willingness to adapt to circumstance. The example below looks at the game where they were most committed to ball side pressing.

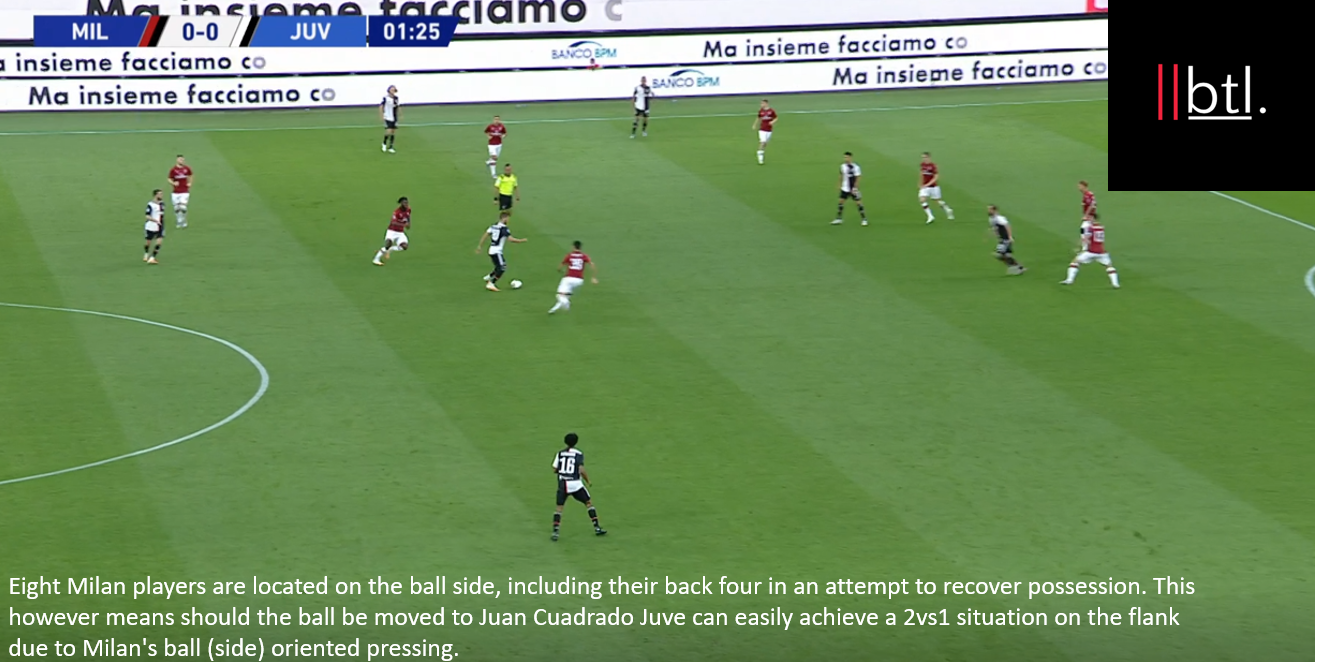

The ball side press that Pioli opted for against Juventus made Milan susceptible to quick switches of play as the opponent can swiftly achieve numerically advantageous situations as for one flank to be overloaded with players, the other must conversely be understaffed.

This approach requires dynamism from Kessié and Bennacer, who are forced to shuttle laterally across the pitch and begin a similar process. As pictured above, often the winger from the opposite flank aids in the ball side press, meaning significant adjustment must occur provided a switch happens.

Conversely, there are significant merits to this approach as it forces sides that want to combat it to commit to building down the flanks, enabling Milan to reduce the size of the pitch and remain more compact and making them more difficult to break down through intricate passing manoeuvres, the kind of manoeuvres that Maurizio Sarri’s sides have been praised for over the years.

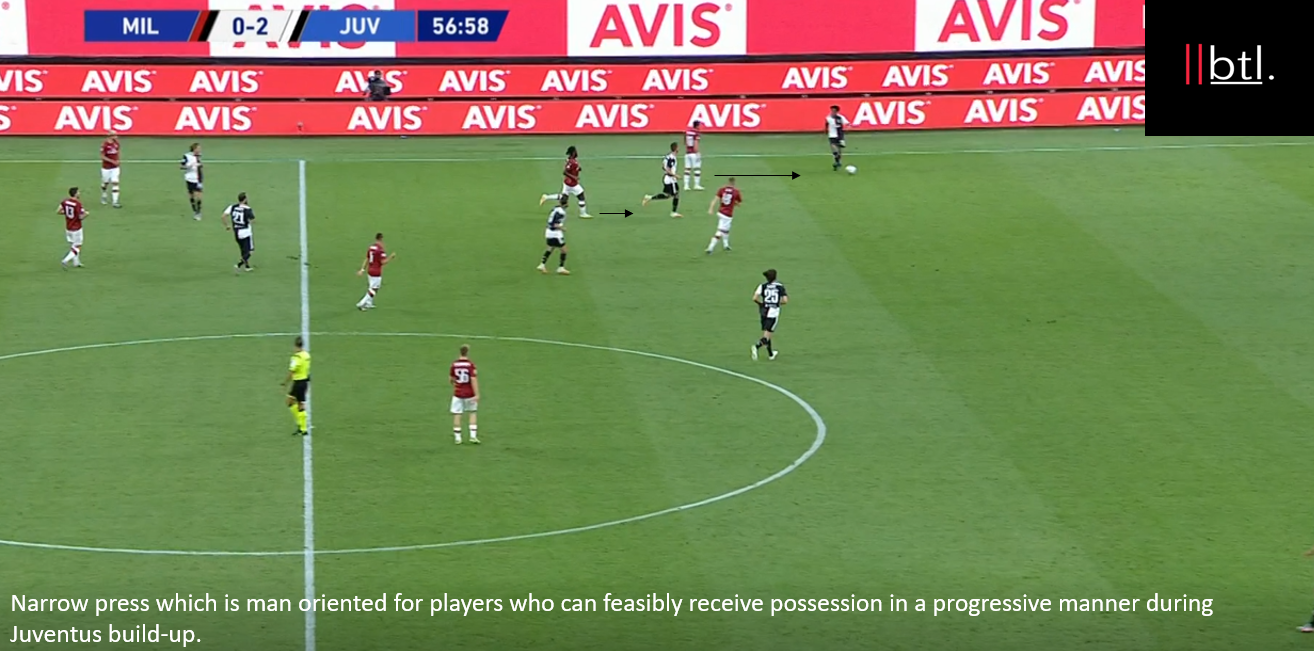

This type of press seems to be more in line with what they seek to do when the opponent has consolidated possession. This is the phase where enough numbers have regrouped to make it possible. Therefore, it is congruent with a zonal-man-oriented marking scheme during the phase transitioning to deeper consolidated defending.

As demonstrated below as when Juventus seek to play out of defence, Milan continue with the set-up they typically use, employing a zonal man-oriented scheme with emphasis on pressing in wide areas.

The commitment is aligned with the opponents’s strategy rather than being rigid, as they committed to this with more numbers in accordance with Juventus high attacking commitment while less so against a less adventurous Napoli side.

Pioli, as noted previously is a pragmatist, with this approach not being used against Lazio because of their narrow formation, instead going for a more zonal approach with central commitment to protect against the likes of Luis Alberto and Sergej Milinković-Savić.

The general principles of Milan’s off-the-ball approach seem to be a touchline press and attempting to reduce the available playing area, and while the implementation of that differs, it largely follows a zonal-man-oriented midfield marking scheme.

In conclusion, the complexity and adaptability of Milan’s defensive system best explains why they hired Pioli on an interim basis initially, as he can adapt to what the situation requires with a unique, fresh approach.

Ibrahimović’s importance in attack means he is a regular starter, however, that makes pressing highly more difficult, and as such, compromises must be made to suit all players. It explains why Pioli has often started Alexis Saelemaekers on the right wing, as the Belgian’s high work rate makes him suitable for covering Ibrahomvić’s deficiencies and engaging an intense touchline press despite a player such as Lucas Paquetá or Samu Castillejo possessing more attacking flair and unpredictability.

The approach has the potential to be exposed by passes in between the lines and that is the area where Milan need to improve most defensively, as relying on the centre backs to cover the space makes them more susceptible to counter attacks.

Looking to the future, it is difficult to envisage Pioli’s Milan without an Ibrahimović-like player as the focal point in attack. However, Pioli has proven himself to always be able to adapt to the squad’s necessities and flaws. Regardless, Milan should not think twice about extending the legendary Swede’s contract due to his on the pitch contributions and the intangible elements having a leader. According to Gazzetto dello Sport, Milan have offered him a one-year extension that would see him earn £104,000 a week if appearance and performance-related targets are met.

Milan have a strong defensive and midfield core with players such as Gianluigi Donnarumma, Alessio Romagnoli, Ismaël Bennacer, Franck Kessié and Theo Hernandez, while the attacking additions of Ante Rebić, Zlatan Ibrahimović and Alexis Saelemaekers have brought a combination of balance and quality to the side. If Milan can build to their current pieces in the summer transfer window, there’s no reason why Pioli’s Rossoneri can’t make a strong push for a Champions League spot next season.

By: @mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno