Le Carre Magique: The Story of France’s Golden Midfield Quartet

Magic Squares are square grids within which every row, column and diagonal adds up to the same number. Used by Arabic astrologers to predict horoscopes as far back as the 9th century, the perfect mysticism of this formula has been noted throughout history.

Reason and logic may denigrate the astrological routes of this theory, but one perfect storm in the summer of 1984 served to undermine this as four improbable midfield metronomes guided France to their first piece of silverware.

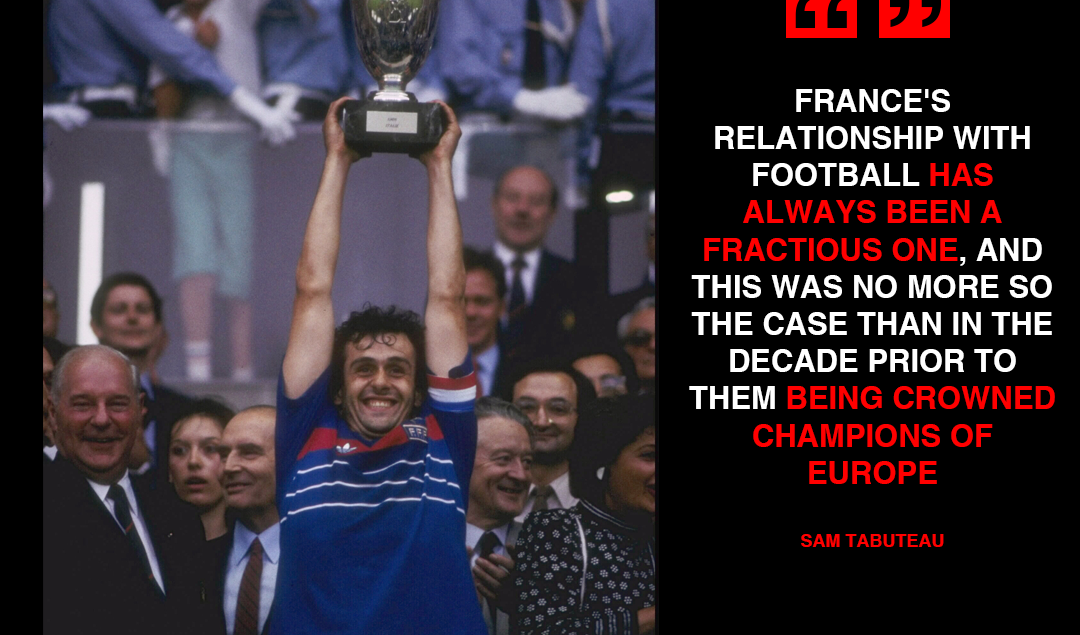

France’s relationship with football has always been a fractious one, and this was no more so the case than in the decade prior to them being crowned champions of Europe. The country’s antipathy towards football and sport in general dates back to its historic socioeconomic divisions and subsequent prejudice.

Even during the success of Just Fontaine and the French national team of the late 1950s, there was a dissenting view that academia held far greater importance than sport, and football itself engendered a sterile working-class environment.

This may seem ironic, given the fact that both the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championships owe a significant portion of their history to the French. Nevertheless, these opinions only served to gather more validation when the national team failed to qualify for three of the next four World Cups between 1962 and 1974.

Saint-Étienne’s rise to the pinnacle of European football during this time restored some level of national pride and enthusiasm. But it was under the guise of Michel Hidalgo and his four horsemen of the apocalypse that football was catapulted into the mainstream of French culture. Herein lies the story of Le Carre Magique.

A subjective disdain for football was of little consequence for Jean Tigana. Born in Bamako, Mali, Tigana was one of only a handful of players from French-governed colonies to be called up to the national team during the 1980s.

As a growing argument over national identity came to the fore of France’s political agenda, the increasing opposition to a liberal but ultimately weak Socialist government among the working class made life increasingly difficult for immigrants of African descent.

The World Cup-winning team of 1998 may have been held up as the role models for a new generation, even if Zinedine Zidane, the son of Algerian immigrants, would go on to dispute this comparison. But it was in fact the tireless and dynamic running of Tigana that paved the way for the likes of N’Golo Kanté, Blaise Matuidi and Tanguy Ndombele.

The modern-day box to box midfield role combines copious amounts of energy and technique, an overwhelming responsibility that takes influence in no small part from the buccaneering displays that personified Tigana’s career.

A slight and wiry midfielder, Tigana imposed himself on French football through an unrelenting desire to press the opposition into relinquishing possession.

His work rate and attitude were second to none, and he endeared himself to fans across the country with his unwavering loyalty to the clubs he turned out for – reportedly turning down moves to Barcelona, Juventus and Tottenham Hotspur.

Having made his name at Toulon and Lyon during the 1970s, Tigana was eventually picked up by Aimé Jacquet – who would later lead France to the World Cup in 1998, as part of a youthful Bordeaux side. Tigana’s defensive discipline suited Jacquet’s pragmatic tactics perfectly, and his composure on the ball also made him an unpredictable offensive threat.

Tigana’s success at club level is undisputed, having collected three league titles and three French Cups whilst at Bordeaux, but it was in amidst a patriotic cauldron of hope, if not expectation, that Tigana cemented his reputation as one of Europe’s finest box-to-box midfielders.

It was the 1984 European Championship, and France’s semi-final with Portugal looked to be heading for penalties. The two sides had exchanged everything from goals to pleasantries over the course of 119 minutes. In order to prevent a nail-biting shootout, somebody had to rise to the occasion and make themselves a hero.

Step forward Tigana, with one final lung-busting run to the by-line. Carried by a cacophony of noise and swirling French flags, he darted through the Portuguese defence and cut the ball back to the onrushing Michel Platini.

One touch to control, one touch to finish, and with that, the enduring image of French football was born. Platini running the length of the pitch basked in the adulation of his country.

It is easy to forget what a masterful player Platini was during his pomp. A three-time Ballon d’Or winner, his ability to drift into space and dictate games from the comfort of the 18-yard box made for perhaps the single greatest individual display in the history of the European Championships.

Whilst the free-flowing movement of Le Carre Magique created the environment in which a playmaker could flourish, it was Platini’s deft touch and sublime dribbling which saw France announce themselves on the international scene once again.

It was not just the quantity of goals that Platini scored across the summer of 1984, but also the importance. He struck the winning goal in the opening group stage game against Denmark, before netting the first of his two hat-tricks across the tournament as France demolished Belgium 5-0, a game that also saw the two remaining cogs of the Magic Square, Luis Fernandez and Alain Giresse, add their names to the scoresheet.

Left foot, right foot, header, it was a hat-trick of the highest order from Platini, and quite remarkably, he would go on to replicate this feat of perfection against Yugoslavia. Left foot, right foot, header. The repetition of the same inch-perfect technique he applied to almost every shot he took was fascinating.

“What a playmaker. He could thread the ball through the eye of a needle as well as finish,”-Bobby Charlton.

Having previously been lauded as the scapegoat for his country’s shortcomings, it seemed fitting that he would banish these accusations with one swift use of his calling card, the whipped right foot free kick. With a goal in each of the five games, Platini ensured that his legacy would remain intact both at home and abroad.

A common theme slivers its way throughout this article — success in the face of adversity. Alain Giresse, for all his technical prowess, was far from the ideal athlete, especially at a time where ‘total football’ was in its infancy. Giresse, a diminutive playmaker renowned for his agility and acceleration, made his name alongside Tigana at Bordeaux.

Romeo Lavia: Southampton’s Long-Term Replacement for Oriol Romeu?

A supremely talented ball carrier, his slaloming runs saw him breeze past even the most physical of players. Calm and composed, Giresse always seemed one step ahead of the rest on a mental level.

He would drop his shoulder with expert timing, shifting his weight from one foot to the other as the ball followed like a faithful dog. His solo effort against Lens during the 1983/84 season is one of the most delectable goals you could watch whilst in lockdown.

“He was a magnificent player, very intelligent with a great technique and an incredible passing ability” – Aimé Jacquet.

His managerial career may have been plagued by police protection, military coups, and the threat of media violence, but as a player, Giresse will be immortalised for the iconic celebration that followed his goal against West Germany in the 1982 World Cup semi-final.

In a game even more widely remembered for Harald Schumacher’s reckless charge on Patrick Batiston, Giresse’s performance was enough to see him ranked second for the Ballon d’Or that year.

This brings us on to the one member of Le Carre Magique to miss out on a Ballon d’Or nomination during his career: Luis Fernández. Born in Tarifa, Spain, Fernández moved to France with his parents at the age of nine, and became a neutralized French citizen in 1981, just a year before he was called up by Michel Hidalgo for Les Bleus.

The then 23-year-old had established himself as a superb ball-winning midfielder with an eye for a pass whilst at Paris Saint-Germain, and would go on to provide the perfect foil for Platini.

By sitting deep and dictating the tempo, Platini was then able to move between the lines uninhibited. As Fernández took his place alongside Platini, Tigana and Giresse for the first time, few could’ve envisioned the impact this quartet would have.

Bobby Robson’s England were the visitors to the Parc des Princes that evening. Boasting one of the finest midfield combinations in Europe, it was assumed that Bryan Robson, Sammy Lee and Glenn Hoddle would provide stern opposition for Hidalgo’s untested formula. The result, however, was anything but.

Wasteful finishing coupled with a string of excellent saves from Peter Shilton ensured the sides somehow went in level at the break. The quick exchanges between Fernández and Platini were dragging England’s defence all over the pitch, with Giresse ducking and diving into the pockets of space that were left vacant.

Almost upon the hour, France would find the breakthrough, as Giresse stopped the ball on the right-hand touchline before bursting away from his marker and crossing for Platini to head home. Platini would later drive a free-kick through an almost impenetrable six-man English wall to cap off a resounding win for France.

Their first performance as a quartet would become a staple of their success that summer – quick-fire bursts of movement capped by an indefinable moment of brilliance. It’s no wonder that England neglected to televise large portions of the tournament that summer. They were duly outplayed by arguably the finest midfield quartet ever to grace the beautiful game.

By: Sam Tabuteau

Featured image: Gabriel Fraga