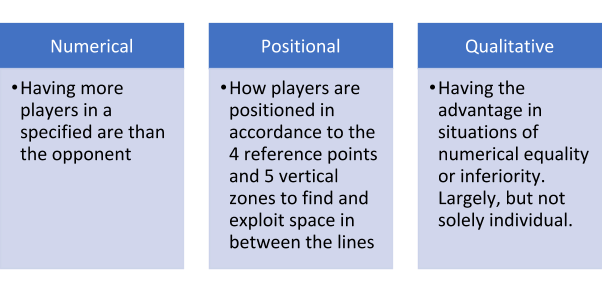

Conceptualising Superiorities in Football

One of the crucial concepts to understanding positional play is that of superiorities as they dictate in practical terms how to be decisive in the respective phases of possession. These superiorities are numerical, positional, and qualitative. In this article, I will investigate the process of how these superiorities are achieved.

Numerical Superiorities

This is perhaps the easiest of the three to understand because it simply refers to having more players than the opponent in a specified region of the pitch with the alternatives to superiority being equality or inferiority. It provides the launching pad for positional play because it allows the team in possession to consolidate and provides the stability necessary to circulate.

It thus establishes a game state of control required when facing defensively organised sides. Axiomatic to a numerical superiority in the build-up is that of inferiority in more advanced regions because there is numerical equality provided both sides have 11 players. Transitions cannot be quickly achieved unless the positional superiority has been achieved through numerical superiority. Thus, effective use of numerical superiority is important as committing greatly to it will prevent future progression at the cost of present stability.

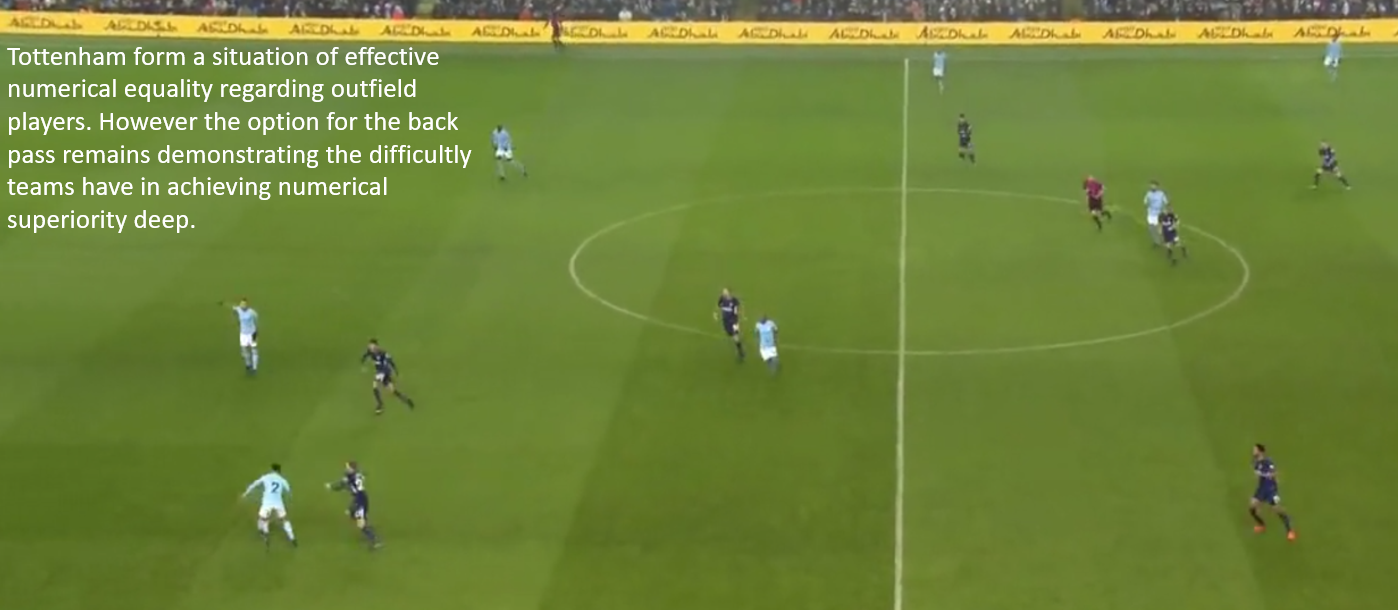

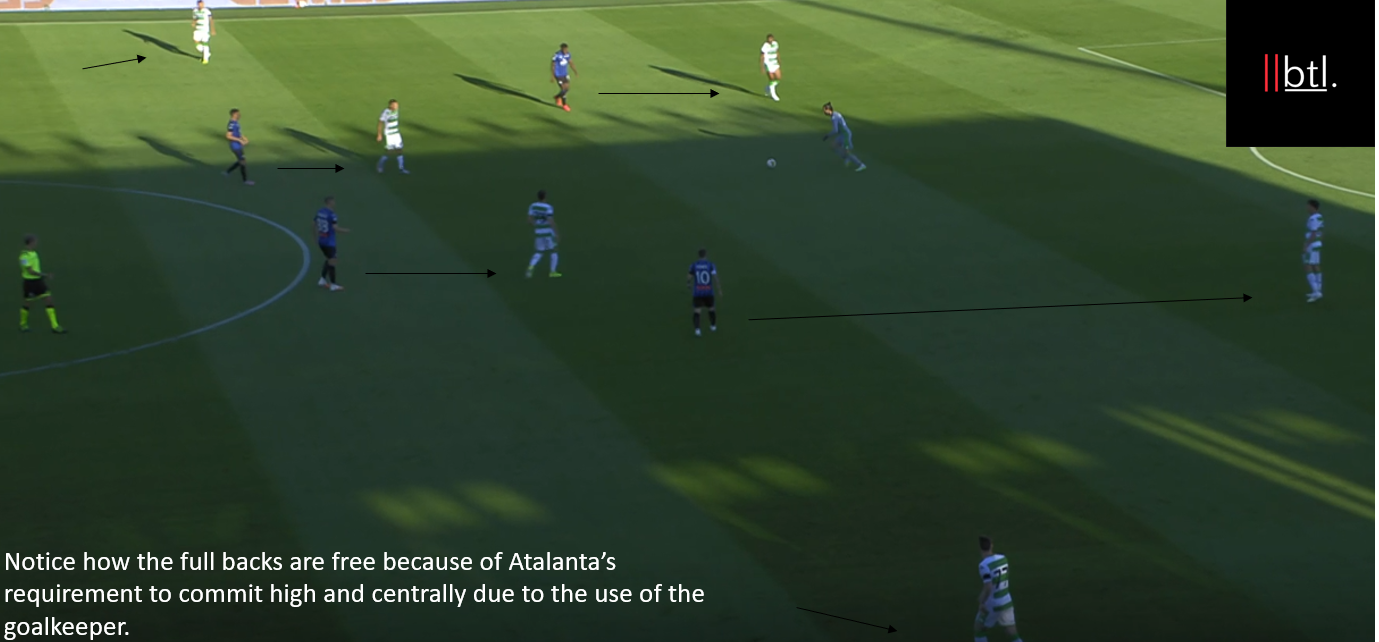

It is typically easy to achieve numerical superiority during build-up as the only way to achieve numerical equality against a team during build-up is to opt for a man-oriented approach, however even in those instances when building deep the goalkeeper can become an active figure thus making it extremely difficult to ever achieve numerical equality fully in deep regions.

Thus, there is always a +1 as the goalkeeper can become active. However, as more territory is gained, this is a less viable option. However, teams such as Antonio Conte’s Inter Milan commonly go backwards to the goalkeeper to restart attacks to establish control of a game through the extra player thus further reinforcing the importance of control as it pertains to numerical equalities.

This control thereby leads to opportunities whereby they go backwards to go forwards, where the space exposed to force the back pass to the goalkeeper is exploited. This can moreover allow for situations of transitions to occur more easily due to influencing the spacing between the opponent’s defensive lines should they react to long backwards vertical passes.

Therefore, while tangible progression is not always made, a positional superiority can be more easily achieved due to the stability provided by the numerical superiority and the reduced compactness of the opponent creating the potential for a transition.

If the opponent reacts to the commitment of players in the build-up with their own commitment, this is considered ‘moving’ the opponent through stretching them and thus exposing space in higher regions of the pitch which can be attacked directly or through short progression.

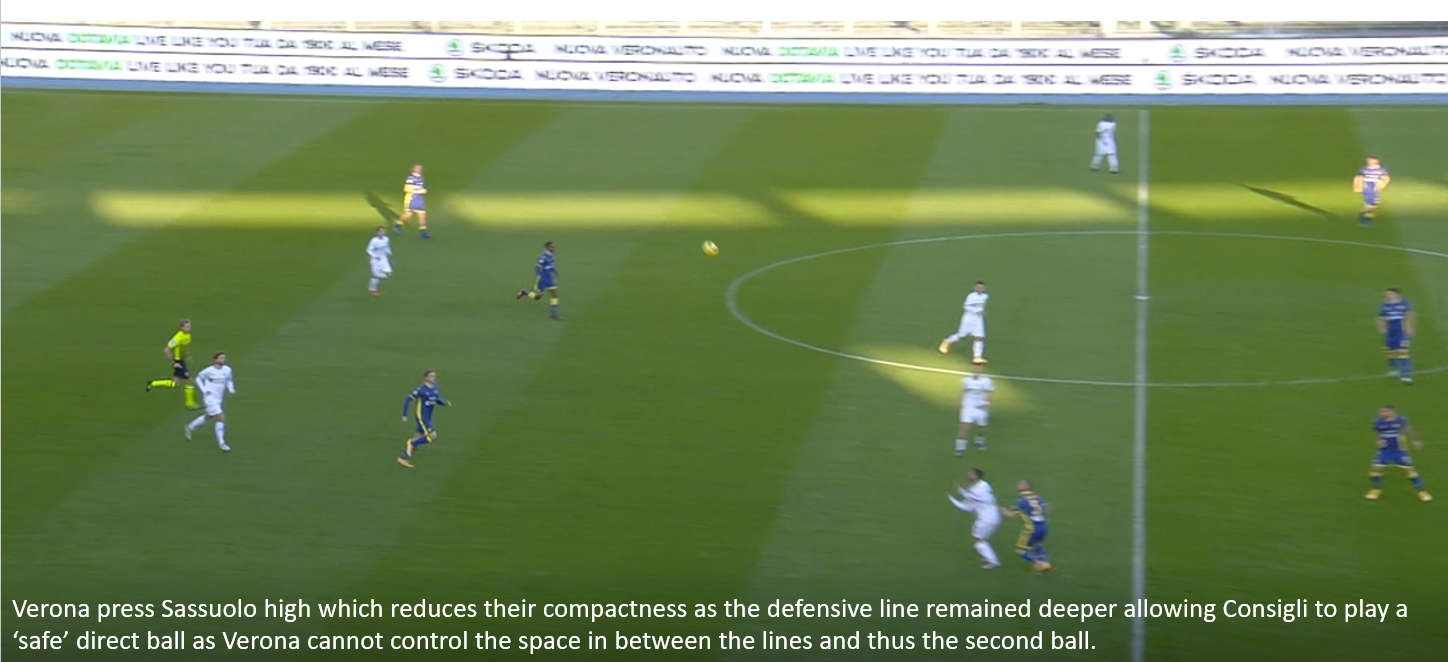

Thus, direct passes which achieve the positional superiority to allow for transitions can still be considered an externality of seeking to achieve numerical superiorities in deeper regions as through drawing players forward, space is created in more dangerous areas. Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City commonly do this against teams which seek to press them high, using the distribution of goalkeeper Ederson to create results from the opponent attempting to match them numerically.

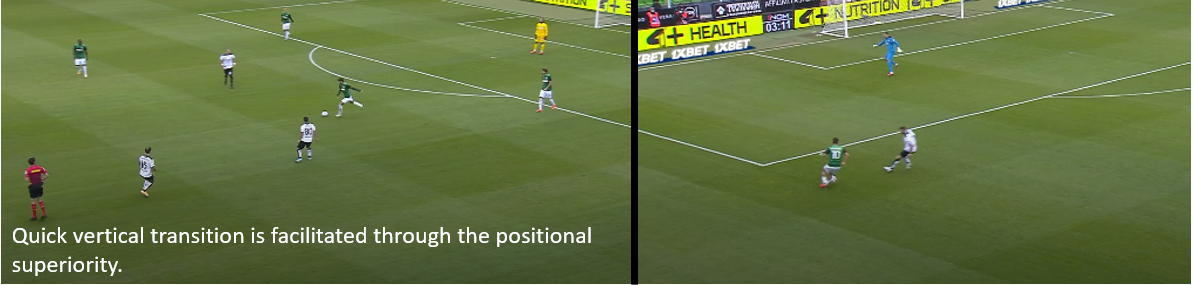

The numerical superiority is all about creating the opportune moment for verticality, therefore if that is created through the opponent’s voluntary movement, positional play teams should capitalise. The aim is to move the opponent, take control and force constant reactions. Therefore, the direct ball and control of the second ball should not be ignored, as they are effective tools at capitalising upon an opponent’s desire for numerical equality deep.

Part of what makes playing out of defence so effective is the difficulties with which it is countered as numerical commitment allows the team in possession positional superiority if duels are not won. Consequently, the team in possession has control regardless, either through short-build and consolidation through the free man, or exposed space vertically if the opponent lacks the players to win duels.

High commitment can create states of transition for the attacking team quickly, as building the launching pad for attacks becomes less important or more accurately, the launching pad is created through the opponent’s movement which is influenced by the numerical superiority. Therefore, situations where the opponent prepares around short distribution and thus leave themselves exposed to the long ball only occurs because the alternative of playing short which is predicated on numerical superiorities exists.

Proficiency at building short makes going direct more advantageous as more of the opponent’s resources are committed preventing short progression which grants them less compactness (because players cannot be offside in their own half ergo the centre backs need to be near that region if the goalkeeper plays a long kick) and control of the second ball accordingly.

Even when it is not directly required to provide stability, it is still crucial in facilitating the transition. The high commitment of players from the opponent often coupled with the lack of compactness due to vertical stretching creates artificial counter-attacking situations, which as noted in the introduction, are beneficial to the attacking team for allowing quick progression as the opponent lacks control defensively.

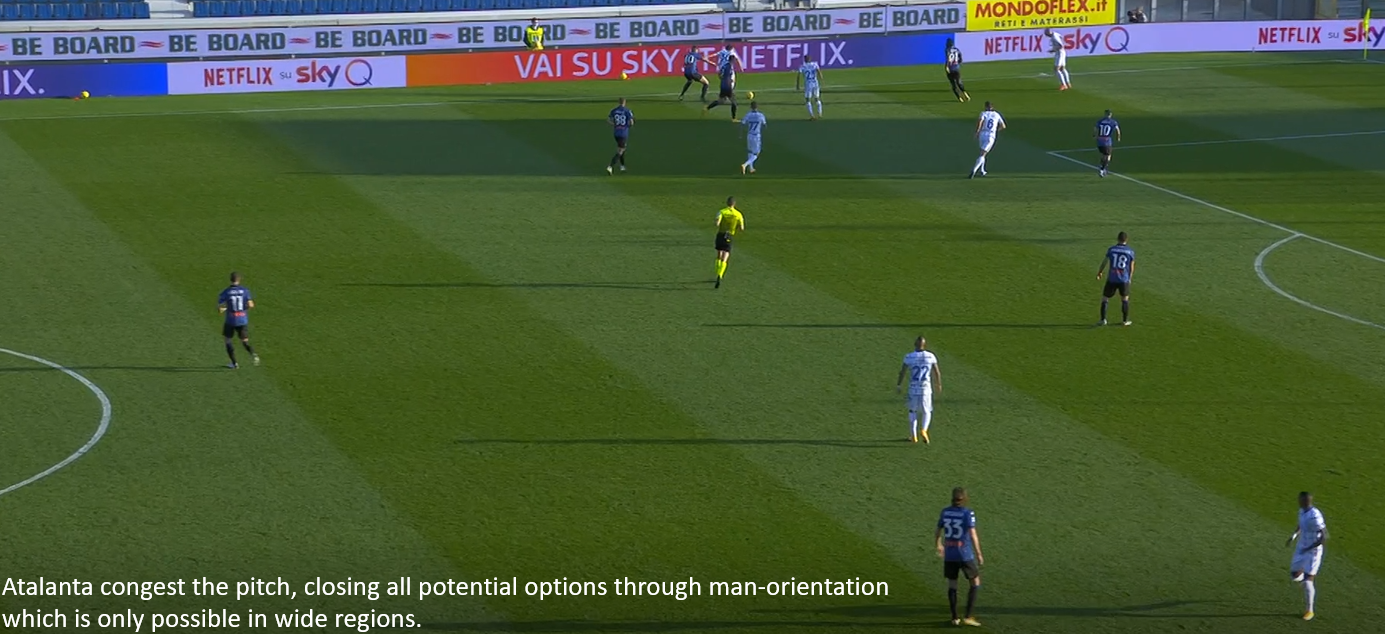

If the team in possession chooses to build short even when facing high pressure, which is typically preferred due to more control being offered as not all teams have a goalkeeper with the distributional abilities of Ederson, the opponent will seek to manipulate effective space when pressing high to form localised equalities or superiorities.

This is typically achieved through attempting to direct play into wide regions to capitalise upon the constraining effect of the touchline. A central focus and central control are paramount in maintaining numerical superiority as it makes it difficult for the opponent to cover the full length of the pitch.

This central focus makes the goalkeeper extremely important because they are typically the most central player in deep regions. They can be a useful tool for attaining control by acting as the free man in addition to the opponent sacrificing an outfield player to pressure them, and through forcing greater pitch coverage both vertically and horizontally as the opponent has greater ground to cover thus making short and long distribution more effective, as a passing lane must open if the players around the keeper move intelligently and long due to the compactness/coverage conundrum.

Defending teams are aware of this and therefore often position themselves as to allow the initial wide pass and then subsequently engage in the press afterwards. Thus, compensating numerically in the centre though leaving wide options open only to coverage afterwards and hope to form parity.

In summation, numerical superiorities are not limited to positional play because in many instances they are naturally occurring in deeper regions. Moreover, their utility is recognised by most teams attempting to build short and bypass pressure to consolidate pressure/transition. What makes positional play interesting is how this advantage is used, and potentially not required, although always helpful.

Positional Superiorities

It is broadly agreed upon that there are four phases of play in football: consolidated defending, defensive transition, attacking transition and consolidated possession. There are issues with this approach in that the arbitrary moment at which one phase switches to another can be difficult to discern and teleological as far as each moment is not trapped within its own microcosm.

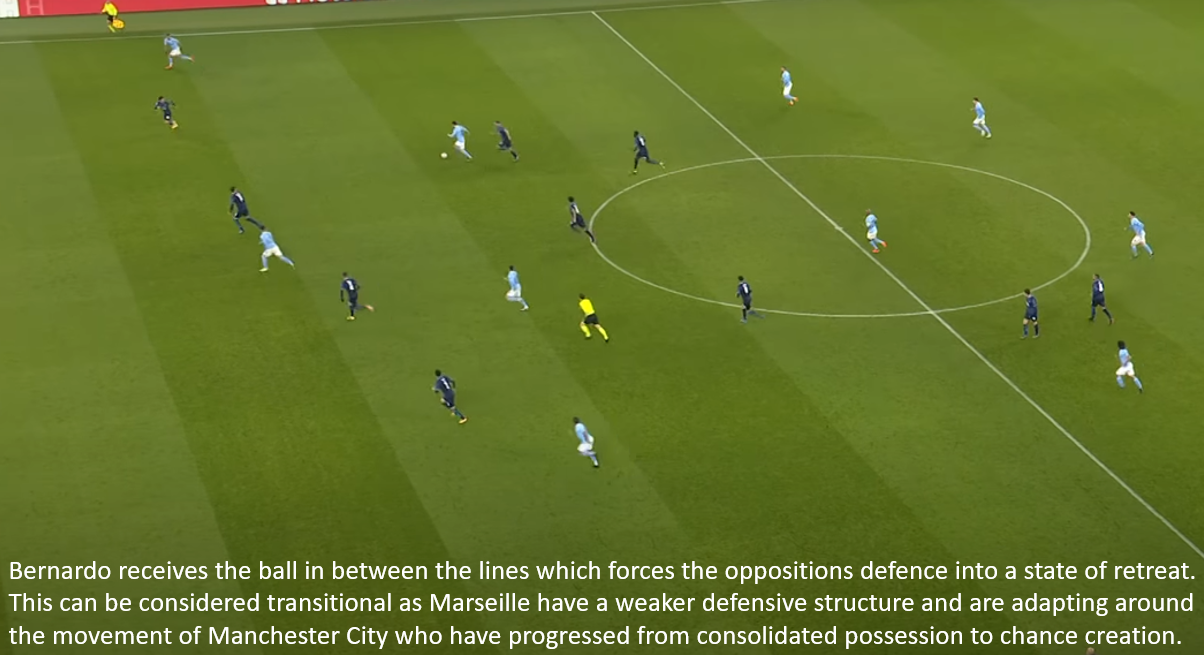

There are various resulting possibilities from any action, however, whether something is considered an attacking transition, for instance, is predicated largely on outcome despite a constant segment theoretically encompassing an attacking transition should events have transpired differently. For instance, envisage two scenarios. A midfielder passes back a centre back, who plays a lateral pass to the other centre back which results in a line breaking pass to an attacking midfielder.

In scenario 1, the attacking midfielder plays a through ball and the team are now transitioning. In scenario 2, the attacking midfielder decides to play a lateral pass to a winger, which leads to possession circulation. In scenario 1, I would consider the start of the transition the line-breaking pass, as exemplified in scenario 2 the wider context is important because it is still contingent on progression afterwards and thus many would not consider it a transitional passage because of the aftermath. This raises the question as to whether it can be considered the start of the transition all together or the start to a potential transition.

This may seem semantic and esoteric, however, when discussing the positional superiority, it becomes important. Moreover, issues such as the conflation of attacking transitions and counter-attacks are problematic as although they produce the same game state and are not inherently dichotomous as all counter-attacks are attacking transitions, not all attacking transitions are counter-attacks. Nonetheless, it is a useful tool for understanding the tactical approaches of teams in response to a dynamic game.

In response to the aforementioned conflation, a dichotomy of control can be created to further categorise which is particularly useful when analysing through the prism of positional play. Transitional states are those in which the defensive side is not in control and are constantly adjusting and compensating in a semi-spontaneous manner (ranging from instructions of what to do if a certain situation of unpredictability arises to completely fragmented decision making) manner.

Conversely, consolidated phases are those in which the defensive side are in control meaning the tempo is likely low and the ball is being circulated. The aim of positional play is to create occurrences of transition, moving the opponent and forcing them to constantly react, and therefore lose control. The primary utility of positional superiorities is to create moments of transition, this is as the opponent loses control of proceedings.

When you find the free man there is space. They are achieved through various means, however, as it pertains to positional play there are a set of principles and practices. Positional play coaches split the pitch into 5 different vertical corridors where optimal positioning through staggering is sought to help find players in between the opponents’ lines of defence and transition towards goal.

Through positioning themselves in between the opponent’s lines of defence horizontally, the players force movement upon reception, either forward aggression (deep line) which leaves space exposed in behind or backwards recovery (advanced line) which allows for territory to be gained and other passing angles to open because the line in front which has been breached has to adapt quickly.

Teams out of possession emphasise compactness as it allows them to quickly converge if lines are broken to nullify potential threats. It can also be argued that the best positioning in between the lines is equidistant between the two oppositional reference points (deep and advanced line) because it is more likely to cause confusion as to which players responsibility it is to close (potentially both), and it permits the greatest amount of space vertically and thus time in possession. Creating the situation and conditions for transition.

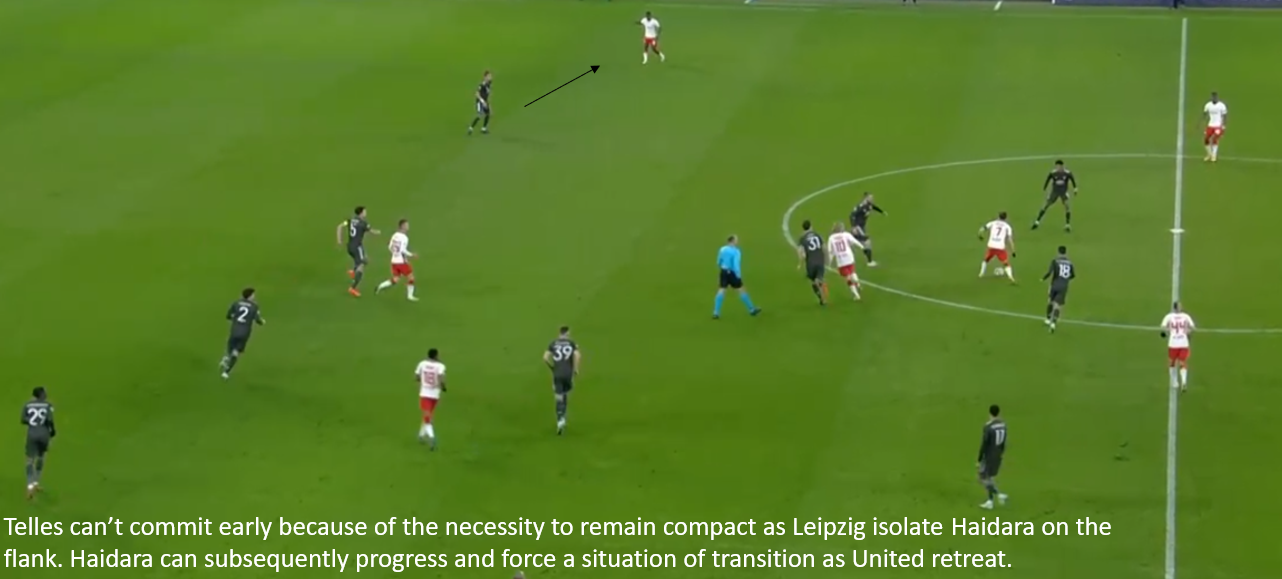

However, it is moreover important to ensure there are players with the responsibility of vertical stretching as to provide the potential for infiltration which forces a defensive line backwards, thus leading to reduced compactness or territory gained dependent on the responding action of the midfield line thereby drawing space for the ball carrier or potential receivers in the form of a decoy run.

Alternatively, the run serves the purpose to receive the ball, with the two aims not necessarily being dichotomous. For players to receive in the between the lines effectively, there should always be a player at the deepest point.

This can be achieved through a deeper forward with vertical stretching coming from wide and inwards to more dangerous central areas i.e Harry Kane and Heung-min Son or through a more advanced forward. The crucial point to consider is there needs to be a player to receive in between the lines and a player beyond the last line. The composition is largely dependent on the skill set of personnel.

Wider vertical stretching moreover creates the potential for progression due to the space afforded as teams seek to remain compact, and the emphasis on protecting central zones potentially creating a reticent for the opponent to close the player down.

Vertical stretching often causes the defensive state of retreat, which is transitional and characterised by a loss of control defensively with constant compensations and often disproportionate focus on the ball. It is thus, a common method used to create a positional superiority.

This is predicated on the importance of a central focus, or more so the ability to create a free man centrally as the danger they pose during build-up often results in them being pressed thus creating space elsewhere. During the build-up, it is generally opportune to keep the ball as central as possible when possible as to stretch play, although opponents correspondingly adapt around that requiring strategies such as overloading to isolate.

Stretching the play helps create free men in wide regions otherwise, attempting to cover them will create passing lanes centrally. I covered this in more detail here: Tactical Analysis: Compactness and Coverage in Possession – Breaking The Lines.

Roberto De Zerbi’s Sassuolo keep their wingers high and wide when building up which forces the opponent to stretch their lines of defence to cover for potential penetrative movement stemming from a long pass. This provides a direct outlet without the need for physical superiority and adds threats to central possession as it is impossible to simultaneously cover both players and remain compact, with both players being open directly due to the ball being in central areas.

Increased effective coverage of the pitch in possession is another way to achieve a positional superiority by forcing the opponent to consider the compactness/coverage conundrum and making the trade-offs larger. The positional superiority critically is what facilitates transitions through disorganising an opponent’s defence.

The positional superiority is not an entity which exists naturally, but rather is something that is crafted through the intelligent spacing of players which allows for ball circulation and manipulation of the opponents’s positioning. There are four reference points (ball, opponent, teammate, space) which are difficult to separate to show the utility of each because of how interconnected they are.

The positioning of the ball dictates how the opponent and your teammates react, which simultaneously impacts the position of the ball, as to how players space themselves dictates where space is which is to be exploited and thus where the ball will be moved to, which thereby dictates the positioning of opponents and teammates.

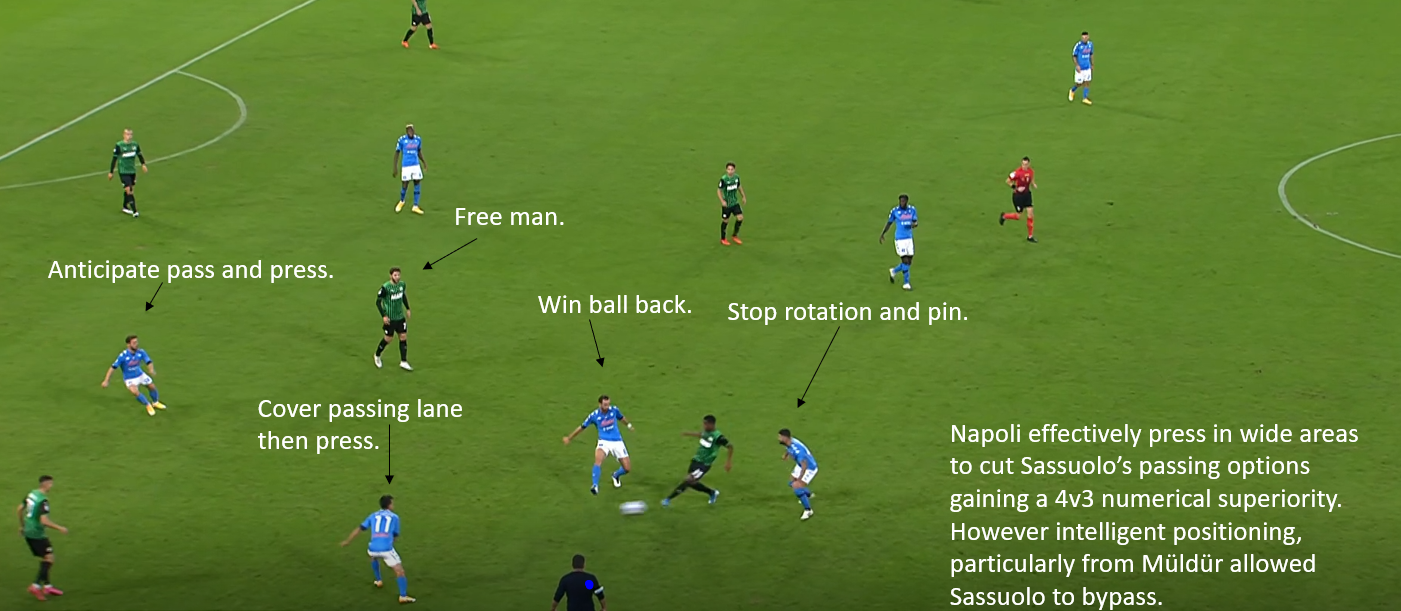

They are constantly interacting, forcing reactions. To demonstrate this, Sassuolo were shown out wide and subsequently pressed on the touchline with Napoli’s 4-4-2 shuttling allowing for a 4v3 to occur.

However, Sassuolo were able to bypass it because of their intelligent positioning. Napoli were focused on the movement of the ball, while Sassuolo were focused on the movement of the opposition, the ball, where space would be and their teammates which allowed them to overcome the numerical disadvantage. This positional superiority manifested itself in part because of the respective body positions of the players, these two individuals acted as their teams in microcosm.

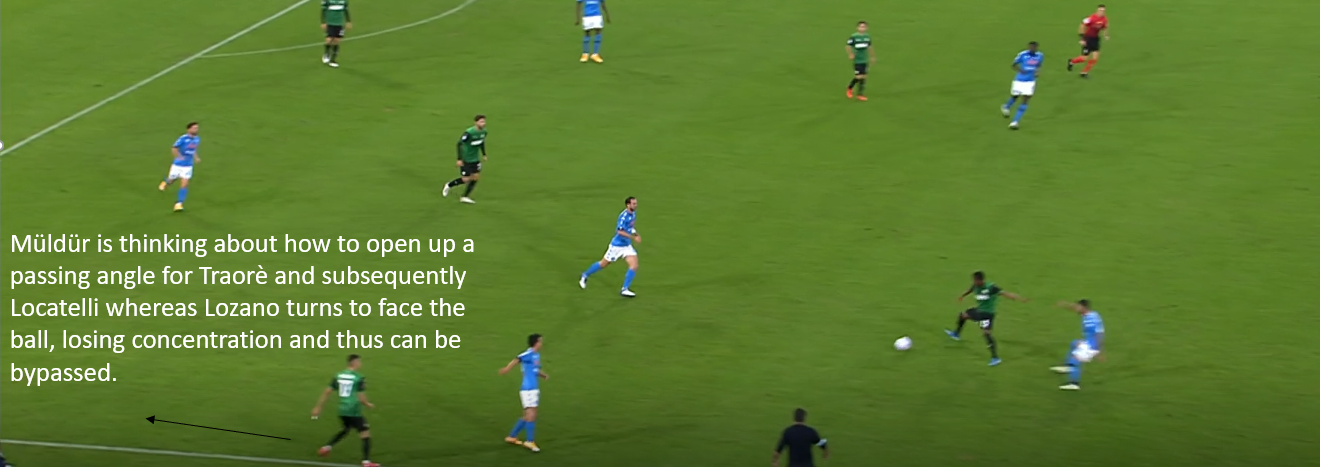

Hirving Lozano is focused on the ball, Mert Müldür is oriented around on how the opponent is moving, where the ball is and can be, where his teammates are and where space will be and thus how to react to create a passing angle, and ultimately to find the free man in Manuel Locatelli.

Analysed through the prism of the 4 reference points: Müldür sees the positioning of the opponent which is a pinning action on Hamed Junior Traorè in addition to Fabián Ruiz closing him down, which informs him that direct progressive options are unlikely, and he drops to increase the size of the effective space Traorè can play it into.

Fabián’s movement means Müldür will be the free man for this one action (rather than the sequence holistically) as Fabián has the angle to Locatelli covered through his movement meaning it is not a direct possibility, triggering Dries Mertens to close down Müldür.

By positioning himself laterally to Locatelli, Müldür prevents Mertens onrushing movement from being able to cut the passing lane, as if he were too deep in relation to Locatelli a negative option rather than lateral would have been the sensible decision as Kaan Ayhan would have become the free man due to Mertens being able to cut the passing lane.

Locatelli can catalyse the state of transition quicker due to having higher positioning and a close connection to Maxime Lopez to move the ball. Lopez in this instance is the support player pass in microcosm whereas his Italian teammate was previously as the free man does not remain free for long durations of time.

Sassuolo can be considered to have the positional superiority despite not having the numerical superiority (although the two are not dichotomous) because they considered the four reference points whereas Lozano placed disproportionate emphasis on the ball.

Also highlighted in this sequence is the importance of connections after a pass has been played. How to establish connections is moreover influenced by the four reference points, as the connection creates the free man for the next action. Traorè receiving the ball implied to Locatelli that Müldür would receive possession, and thus the necessity for a connection, with Müldür signalling to Lopez.

This particular move did not require much manoeuvring from players to form the connection due to the 3-4-3 as a base shape establishing progression paths. However, the next action is always crucial in the positional superiority as the free man does not stay free for long, thus, to capitalise on the short window of opportunity to continue the state of transition, quick movements facilitated by connections are required. The principles of positional play (4 reference points + 5 corridors) allow for this process to be dynamic, thereby enabling transitions as connections can be easily found.

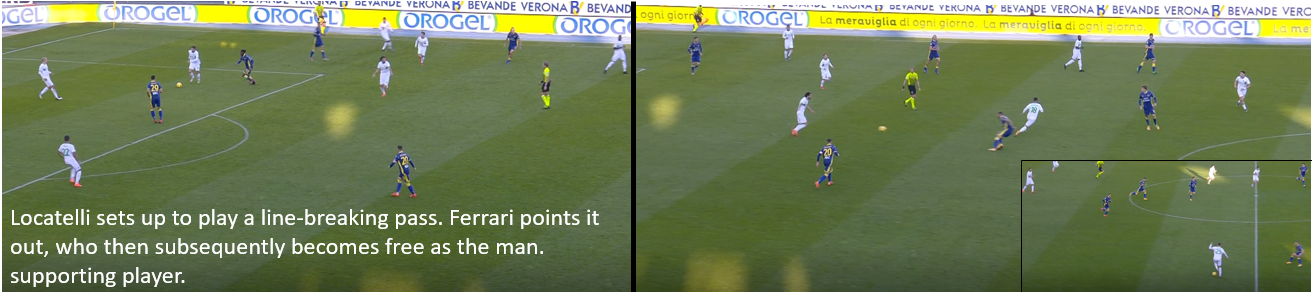

Another sequence to demonstrate this comes in Sassuolo vs Hellas Verona: Locatelli plays a line-breaking pass to Giacomo Raspadori, rather than implied in this instance, Gian Marco Ferrari explicitly points to make the pass, with the implication that he will receive because he is not covered from Raspadori’s angle and thus becomes the free man.

Displaying his purpose as a connection player, as Locatelli’s pass while technically brilliant, is much less effective if Raspadori cannot quickly release it to continue the transition. This subsequently allows for the continuation of the transition as Ferrari finds Domenico Berardi in space due to Hellas Verona’s heavy commitment towards the press.

The launching point of the transition is up for debate – was it Locatelli’s vertical pass or Ferrari to Berardi? I would argue it was Locatelli’s pass as it provided Sassuolo with the ability to transition through breaking the press, but there was no inevitability about it being capitalised upon. The transitions relevant in this piece are contingent on support structures when formulated through in possession mechanisms, rather than out of possession mechanisms which are more important in counter-attacks.

Positional superiorities are therefore the cause of, and catalyst of transitions. For a state of a potential transition to be created in possession a positional superiority must be attained to manipulate the opponent’s defensive structure to create space. However, for a transition to be considered a transition it requires connections.

Verticality to break lines is an essential element of disrupting an opponent’s defensive structure, and often the start of transition through forcing reactions to close the man, however without an adequate support structure, a team cannot capitalise and therefore a transition occurs.

Thus, the difficulty in defining how and when a transition starts. However, it is conceptualised, though, it is much easier to achieve when players are positioned intelligently to receive passes and are aware of the relevant factors thanks to considering the 4 reference points.

Qualitative Superiorities

Potential transitions however do not always fail because of bad structure, but rather an inability to execute the required actions to facilitate it. Moreover, the state of transition potentially occurring moreover is not inevitable, as not all players possess the passing quality, for example, of Locatelli to break lines and thus player quality as well as the structure is crucial.

Photo: Emilio Andreoli/Getty Images

You need players who can capitalise upon the situations created; how good a structure is, is often dependent on how contextualised it is to the strengths of its players. Therefore, coaches attempt to create qualitative superiorities to maximise the strengths of their players and thus the system more generally. A typical example is to attempt to isolate a winger with a full back.

Having a qualitative superiority is essentially the idea that not all situations of numerical equality are equal, and thus attempting to isolate players 1v1 or form patterns based upon the strengths of a particular player or set of players can be an effective way to establish advantageous conditions.

My favourite example was Mario Mandžukić under Massimiliano Allegri at Juventus. The Case for Wide Target Men: Investigating Mario Mandžukić and the Role Overall – Breaking The Lines However, a contemporary example is Romelu Lukaku at Inter Milan who through using his strength at holding up the ball, brings others into play, creates dribbling opportunities and accordingly has an attacking system built around him.

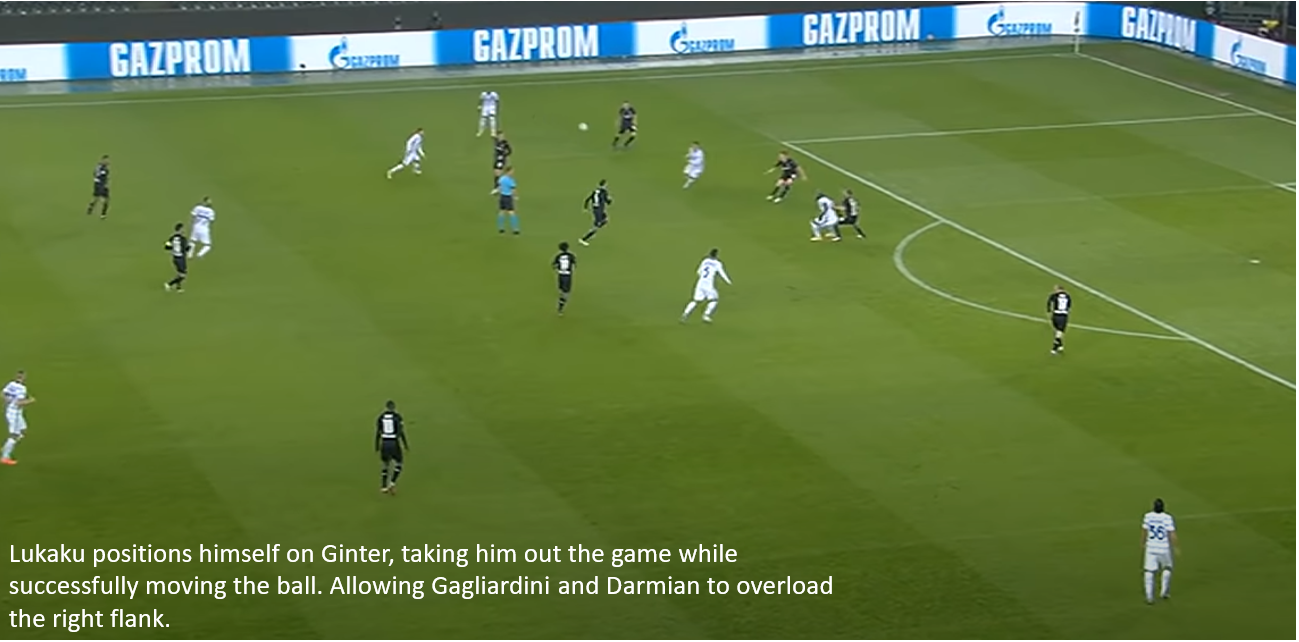

To illustrate his strengths and how the system is adapted around him, I will investigate Inter’s most common build-up pattern this season. The wide right centre back goes wide, adopting the positioning of a typical full-back, whilst the right wing-back either goes high and wide or inverts, with the right-sided midfielder or attacking midfielder depending on formation coming to support.

All these thus far are nameless because the pattern is not contingent on them individually, although the preferred arrangement has Milan Škriniar, Achraf Hakimi and Nicolò Barella occupy these positions. The crucial player is Lukaku, who drops deeper, typically dragging a centre back off whom he leverages off of in order to either spin or bring others into play through the vacated space via a rotation.

Most notable here is Lukaku’s use of his body to hold off the centre back. He can consistently beat his opponent in a physical duel (he moreover uses his body intelligently, it is more than just strength, however, it is the most important component) which allows for this method of progression to be used so regularly.

Marco Rose’s Borussia Mönchengladbach attempted to counter their second half against Inter by making Denis Zakaria responsible for Lukaku, but it ultimately failed with Lukaku winning the duel more often, demonstrating the power of the qualitative superiority in negating the opponent’s tactical plan.

Moreover, the Belgian purposefully positions himself on the centre back, effectively taking them out the game, which is particularly dangerous when there are two onrushing supporting players, typically with only the full back covering resulting in potential overloads. This quality manifests itself in other more spontaneous occurrences additionally because it is a useful skill for bringing others into play and drawing fouls which are fundamental elements of playing in a strike partnership.

Inter’s style of play which is predicated on runners from deep and direct balls over the top is only attainable through qualitative superiority. Hence, qualitative superiority allows interesting formulations and plans because of the individual difference’s teams have.

Very few players have the skill set required to hold off any defender, provide a threat individually on the counter through spinning and play through passes into space. Therefore, attempting to replicate in totality what Inter do with Lukaku is difficult.

Qualitative superiorities make differences across the pitch because of how they influence what a team is capable of, but they are most potent in the final third because achieving numerical and positional superiorities are more difficult due to the necessity to have players back defensively to defend against counter-attacks and facilitate sustained pressure. The facilitation of sustained pressure is an interesting facet of the qualitative superiority because it is an offensive tool made possible by having high-quality physical centre backs who can cover large distances of space and reliably win their duels.

To commit men forward to attack in high numbers, there must be sufficient cover as to not leave a team exposed. However, what structurally defines sufficient cover often comes down to the relative quality of the centre backs. Sergio Ramos for example can be left to cover for precarious circumstances than other centre backs because of his aggressive play style and high success in winning duels.

With players like Ramos, being exposed to these precarious situations is not as dangerous when you have a player of his quality covering, which can swing the risk/reward of committing another player to attack. Some of the best attacking sides often require qualitative superiority in defence to a greater extent than attack to allow their play to flourish through numerical commitment.

In conclusion, superiorities are a valuable tool for understanding how teams approach play in possession as they seek to achieve the advantage over their opponent in attack. Numerical superiorities are important in deep possession because they can allow for the establishment of control to progress play. Positional superiorities can catalyse and continue transitions in addition to the establishment of control while qualitative superiorities often give you the edge required to beat teams and are what make every team unique.

By: @Mezzala8

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Clive Brunskill – Getty Images