Tactical Analysis: José Bordalás’ Valencia

Asked to name a managerial villain from the Iberian peninsula, the casual European football fan would likely name Diego Simeone.

A master of the dark arts, dressed in an entirely black getup and often responsible for football that even his admirers would call pragmatic.

More regular observers of La Liga will know that José Bordalás has long since usurped Simeone as the lightning rod for moral editorials on the way football should be.

Sometimes Bordalás wears a white shirt. Yet the above description fits him as well, if not better than Simeone. As if Simeone had spent several years in isolation, plotting.

Whereas Simeone’s skullduggery takes on a visceral and raw Argentine feel, the unnerving thing about Bordalás is that his passion and outrage seem all the more calculated. A notion insinuated by his millimetre-perfect beard and immovable, jet-black hair.

He turned Getafe into an equally well-oiled machine and in under three seasons, led them from the depths of Segunda to fifth place in LaLiga. After five years, Bordalás returned home to the Valencian community to take charge of the biggest side in the region, Valencia.

A club that has always been vociferous in almost everything it does, all of that energy has been reserved for protests of late.

Stripped of ambition by ownership group Meriton, Valencia waded through last season in a daze under Javi Gracia to a thirteenth place finish. The football was poor, but worse than that – the team itself had no sense of why it was there.

As much as implementing his own idiosyncratic style, the biggest problem for Bordalás to address was undoubtedly the atmosphere.

An aggression, a passion and a hunger would need to be returned to the squad. Just two minutes into his first first match it took for Hugo Guillamón to plant his studs on Nemanja Maksimovic’s shin and receive a red card.

A penalty from Carlos Soler put Valencia a goal up and for the next 80 minutes, los che fought, ran, sacrificed, suffered and struggled their way to a 1-0 victory over Getafe. This had Bordalás’ surgical gloves all over it.

When playing with eleven men, the man from Alicante will generally set up in a 4-4-2. One of the two acts as a focal point and ideally is very much a salt of the earth style nine. They must absorb pressure, bumps and knocks, then sweat intelligent football back out.

Within Bordalás’ direct style, this reference point is essential. The one behind could also be desribed as a strike partner, often the first receiver after the ball reaches that point. The forwards are expected to work as a tandem, that too being an old-fashioned nodule of Bordalás’ wider concept.

Behind them, the two central midfielders also form an ‘engine room’ of sorts. Remaining primarily in position, they are expected to control the pressing, the tempo and the height at which the team defends.

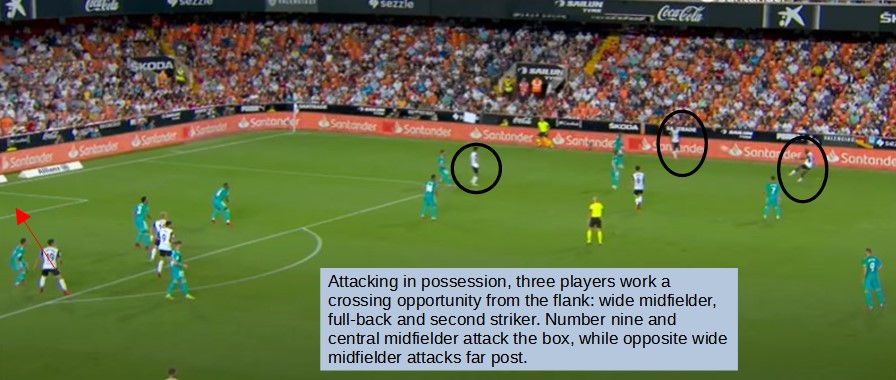

They do have help – the wider midfielders are often set far narrower than a traditional winger. Control is easier with more bodies in the middle and even if Bordalás does not seek to achieve that with the ball, he does want to manipulate the game to a specific pattern.

Should they retain possession, those ‘wingers’ move inside or often into the box, while the full-backs are left the outside channel.

If the preferred method, the quick counter, has been discarded, Valencia will seek to construct attacks down the flanks. Often involving under- or overlaps, they are a conscious part of the supply chain to a populated box.

That first match against former side Getafe felt like the start of something and in their opening four matches Valencia recorded three victories, nine goals, one draw. It wasn’t perfect, but the tenacity and verve were there.

In their fifth match, they fell just short of defeating Real Madrid. Regardless, Madrid had to go through the ringer to take a victory from Mestalla. Pundits and fans were stopped just short of proclaiming it: were Valencia back?

Much to their frustration, those initial matches were probably the closest it has come to Valencia a la Bordalás. Part of this can be explained by key injuries. Yet a much more significant cause is that the man at the helm has been unable to entirely adapt to his players and vice versa.

None more so than in that number nine role. Theoretically, Maxi Gómez possesses the exact set of tools necessary. More than that, he’s a fiery Uruguayan, imbued with all that comes from the albiceleste footballing education – Gómez should be the teacher’s pet.

However, he holds just two goals to his name and not nearly enough associative play to offset that tally. His alternative Marcos André has more pace but just one league goal himself. Neither is he a perfect target man, forcing Bordalás to look for alternate solutions.

These troubles have been paled by the superb performances of Gonçalo Guedes playing off the nine. Clearly the most naturally talented player at Paterna, his nine goals and five assists mean that the Portuguese is responsible for 38% of Los Che’s goals.

Originally a wide forward, he now has the freedom and responsibility to move as he pleases as part of the front two. Ranking fifth in the league for goal contributions, he pleases.

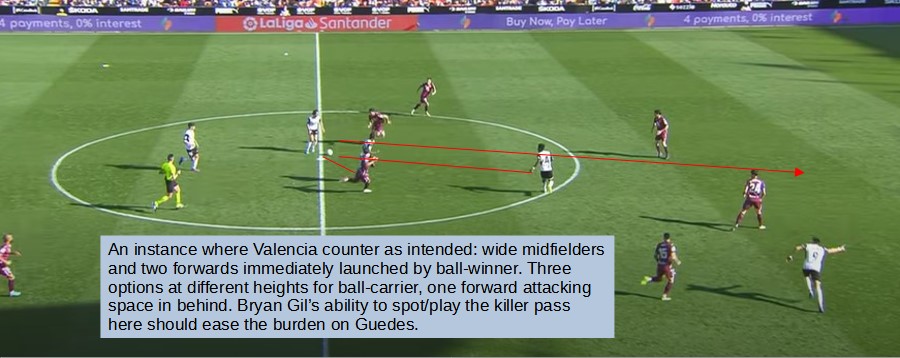

The problem is that he increasingly looks frustrated. So often he is short of sufficient help, making Valencia somewhat one-dimensional. While Guedes benefits from the extra space of the direct football, the creative burden weighs heavy when the space is closed effectively.

Looking back at Bordalás’ Getafe of 2018-2019 helps to explain both that issue and why Valencia lie twelfth. At Getafe, the two-pronged attack of Jaime Mata and Jorge Molina not only had chemistry but were both goal threats.

The first phase of build-up – which involves a ball to the front two then incorporating the wide-midfielders – was flowing through arguably the best associative nine in the league in Molina (save Karim Benzema).

It was direct football but it was a quick, incisive, domino-style attack; now that directness feels loose and hurried. Curiously, this Valencia side are posting marginally better attacking numbers than the best Getafe.

Valencia average a higher pass completion rate (72% vs 65%), more shots on target (4.3 vs 3.4) and more short passes (248 vs 219). Even more goals. But by both eye-test and results, the degree of domination is that much lower.

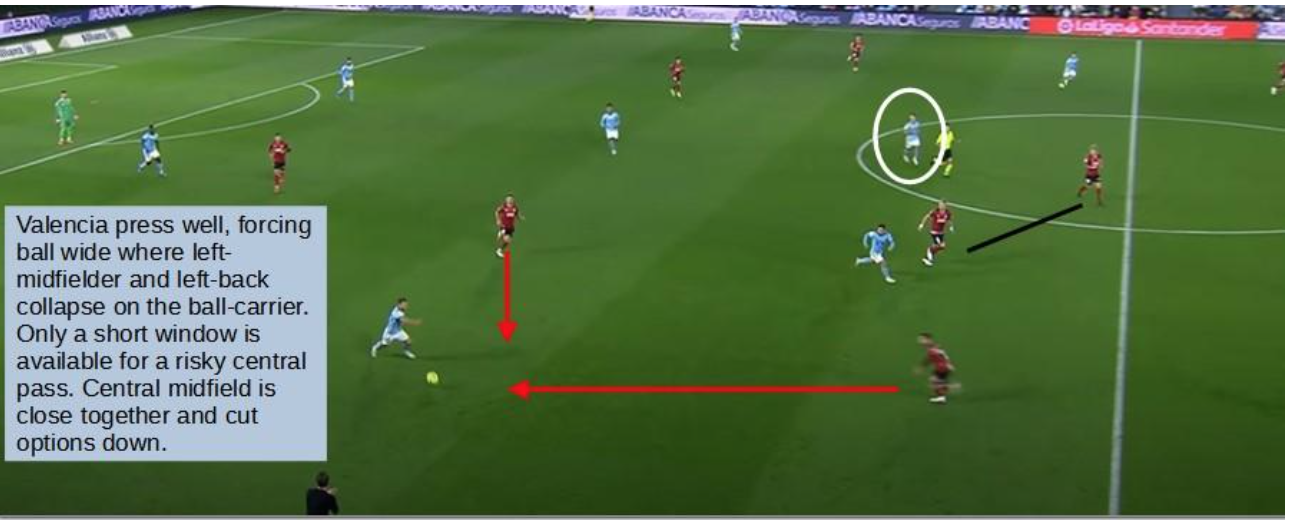

Even though Bordalás is always branded defensive, the one thing that defines his teams beyond ‘mindsets’ is the press. A mid-to-high press is his trademark, yet it’s probably the most notable difference between his current work and the previous one.

Entire matches would be condensed into the middle third of the pitch in Madrid. As soon as the opposition tried to move through it, the attack would be suffocated and the ball pilfered in a matter of seconds.

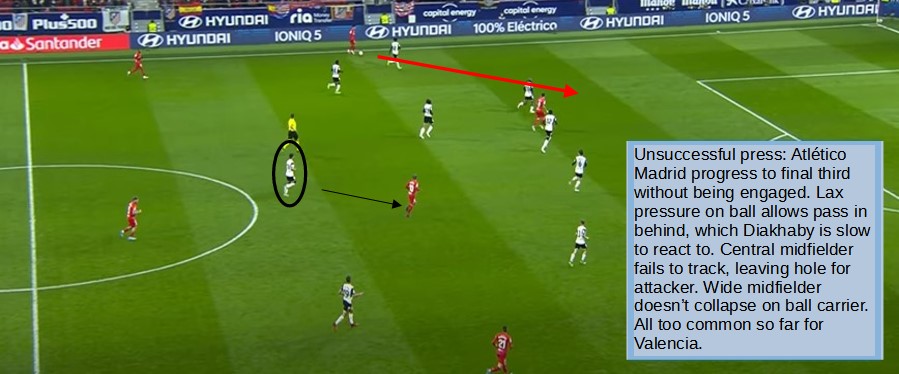

Something in the spine of this Valencia team doesn’t quite move in unison as it should. Instead of boxing off the pitch into manageable chunks, passing lanes remain open a second too long.

Nobody fouls more than Bordalás teams and that’s the back-up plan deployed by every pressing team all the way up to Pep Guardiola. Yet it’s costing Valencia almost a full booking per game more than it did Getafe – the fouls themselves are more desperate in nature.

Robbed of Gabriel Paulista through injury, Mouctar Diakhaby and Omar Alderete are the most common central defensive partnership.

Both are physically imposing, yet so far have lacked the powers of anticipation to play so far from their goal. Equally when Valencia are forced to defend their box, runners are still finding space.

Fifth in the league lie Valencia when it comes to pressures per game; an entirely dispiriting second-bottom they lie for successful pressures.

Peak Getafe were top and second in the same metrics. Djené Djakonam topped the charts for interceptions, while Maksimovic led La Liga in blocks and pressures.

His midfield partner Mauro Arambarri got the silver medal too. The various blends of Uros Racic, Guillamón, Soler and until recently Daniel Wass haven’t imposed themselves in the same way.

This incarnation of Valencia continue to inhabit a halfway house of sorts. Some of the ideas have seeped through, the general intensity has risen since Bordalás arrived and crucially, that purpose is back.

Injuries and absent profiles partly explain this, yet Bordalás will be aware that they are neither consistent or close enough to feeling at home with his style at this point.

The loan signings of Ilaix Moriba and Bryan Gil should be a lotion to some of these issues, in particular Gil easing the creative strain on Guedes.

Both were part of Valencia’s excellent performance against Athletic Club in the Copa del Rey semi-final. With the first leg ending level, victory looks like their only route back into Europe at this point.

Away at San Mames, Athletic were roared on and their warriors were up close and personal from the first minute. In spite of a goal deficit, Valencia responded.

There, we saw Los Che grit and bare its teeth at los leones. The second half was a brutal skirmish. The hosts couldn’t breathe, protesting profusely and mired in acrimony. In other words, playing Bordalás’ game.

If Valencia can channel that energy and tighten up their pressing, it would go a long way to fully converting them to their manager’s cult.

Against Athletic, the adrenaline was palpably fuelling the team. It felt familiar, the opponents agitated and José Bordalás conducting an offbeat orchestra through the anarchy.

Bordalás will want his side to play on the edge, to feed their self-sought villainy. When it worked at Getafe, it was a nightmare on grass. Imagine that at a baying Mestalla?

By: Ruairidh Barlow / @RuriBarlow

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Juan Manuel Serrano Arce / Getty Images