How a Fuel Crisis is Impacting Syrian Football

The Syrian Civil War is so hugely significant that it seems redundant to even try and explain the gravitas of its impact. An eleven-year, enduring and brutal conflict that has left a once great nation with one of the highest numbers of displaced people in the world. The pain it has brought is as terrifying as the prospect of its recrudescence.

As a wintery fog descends over the ancient city of Damascus, many Syrians are now facing major fuel shortages, mounting up the adversities that people face day-to-day. These shortages are the worst the country has suffered, so much so that the UN have declared that 15.3 million people – out of a population of 22 million – are in need of humanitarian need, which is more than any time since the conflict started.

The locals are no great strangers to US-led government sanctions that have seriously hindered access to oil and gas. It is a phenomenon that many countries in the Middle East have become all too familiar with, so much so that natives tend to expect sanctions from their government and are all too aware of the harm these can potentially cause to their routine habits.

Last month, however, marked the first time since the breakout of the Syrian war that the government has enacted a three-day weekend to address the country’s fuel crisis. Moreover, the price of diesel used for heavy equipment in construction and production industries has sky-rocketed, the government has sternly warned its people of purchasing fuel from the black market – something that many people have turned to as a final means – and all cross-city football has been postponed in the Syrian Premier League, as clubs look to save fuel.

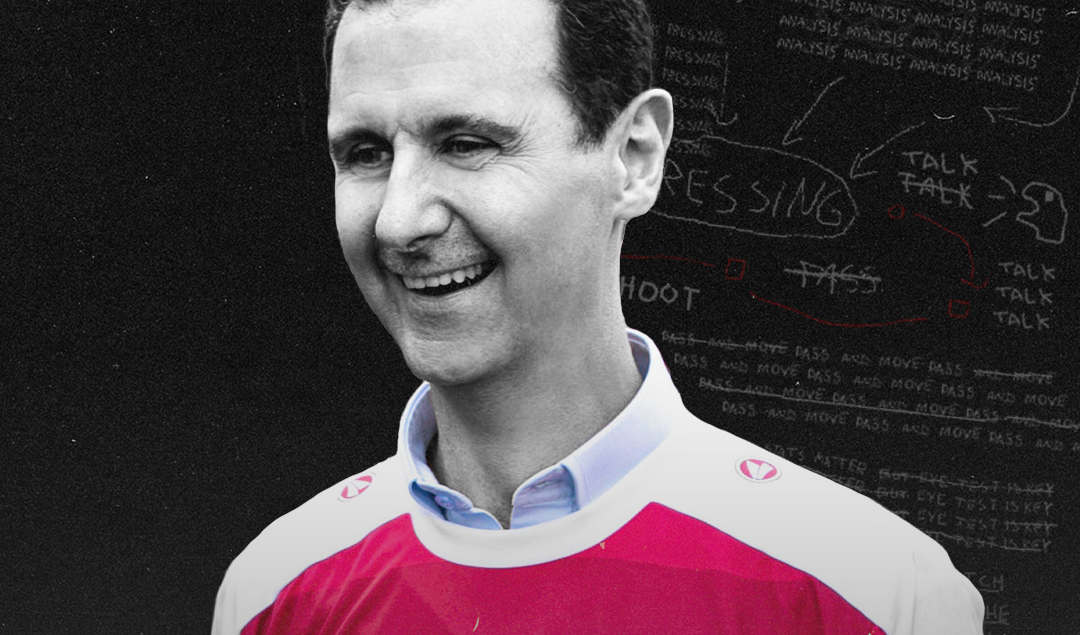

It is worth mentioning that the Syrian football and basketball federations are controlled by the Al-Assad regime and while the lines have always been blurred between Syrian football and the regime’s desire to whitewash their global image, the message here seems to be their insistence on Syria’s fuel shortage being taken as seriously as possible. Even Syria’s private sector industries have ground to a halt amidst this crisis, with many shutting their doors and ceasing operations until the New Year.

A Sepulchral Start

From the outset, this season’s Syrian Premier League started on the somberest of notes. Tishreen SC, based in Latakia, have won each of the last three seasons in Syria. Prior to that, they had won just two league titles – in 1982 and 1997 – but they have become the most dominant club in Syria for the past three years without a doubt. A crucial part of this was Tariq Al-Zeina, who held the position as Tishreen SC president during all three of their domestic triumphs.

Four Things We Learned From The AFC Champions League Group Stage (West)

This season, Tishreen opened up their campaign with an away match to the Deir ez-Zor-based club, Al-Fotuwa. As the players, staff and official made their way to the game, a serious road accident occurred tragically killing Tariq Al-Zeina. This event spun Tishreen into emotional and administrative turmoil and, additionally, the entire league as it had to be postponed and all its matches re-arranged.

Not only was Al-Zeina a passionate supporter of Tishreen who oversaw the most successful era of his clubs’ entire 75-year history, he was also a man with a wife and two young sons. This death left a bruise on Syrian football before a ball had even been kicked in its domestic league.

Rami Saqour, a member of Tishreen’s board of directors said he believed that Al-Zeina’s passing marked a “huge loss for all of Syrian football.” He also described Al-Zeina as “a humble person who worked tirelessly for the sake of his club and its fans.” Just a few short months earlier, the position as head of the Syrian FA was up for election and Al-Zeina did run but ultimately lost out to Salah Ramadan, who previously held the role between 2012 and 2018.

One can’t help but feel a gut-wrenching sense of despondency upon hearing that Tishreen’s fifth league title – which was secured just months before his passing – was Al Zeina’s happiest moment in football. He claimed that that league title had a particular “special taste” that set it apart from the two previous league titles under his reign.

As avid followers of an intensely impassioned sport, we could somewhat relate to the idea of not wanting to miss our teams’ crowning achievements, the one saving grace in what was a shatteringly harsh and sudden death is that Al-Zeina did not miss that. He will be forever embroidered into Tishreen’s fabric, deeply woven into the history of his life’s passion project and that, in and of itself, is just about one of the greatest legacies anyone can leave behind.

Mid-World Cup Detainments

Amidst the tangible excitement and giddiness of the World Cup – particularly a World Cup hosted in a Muslim-majority nation – the streets in Damascus have been lined at times with young people seeking to catch a glimpse of Saudi Arabia’s historic upset over Argentina or Yassine Bounou’s penalty heroics against Spain.

However, the situational occurrence of masses of young men congregating at World Cup screenings spelled an opportunity for the Syrian regime to arrest dozens in a forced military conscription operation. One resident of the Al Midan neighbourhood in Damascus even proclaimed, “Today we watch World Cup, one eye on the screen and the other on the door of the café, for fear of security forces entering.”

Because of the fuel shortage, there is rolling electrical blackouts – even in highly affluent areas of Damascus – which makes it very difficult to watch these games in full anyway. The high cost of subscription to the necessary channels to watch the games makes it an even tougher task to execute. Reportedly, over 30 detentions occurred in just three neighbourhoods in Damascus alone on the first day of the World Cup. And now, people are simply deciding that they are better off just staying at home.

Disenfranchised Populous

The southern city of As-Suwayda has proven to be a relative outlier in Syria’s socio-political landscape. Firstly, it’s a city of mainly Druze faith. Druze is a monotheistic religion that has a 3% minority in Syria, mostly residing in the city. Second of all, As-Suwayda has been spared the incessant conflict that has plagued other cities in Syria and has managed to live a life in relative peace when compared to other major cities.

The last two years however, have bared witness to some extreme anti-government protests in As-Suwayda. In 2020, Prime Minister Imad Khamis – who served under President Bashar Al-Assad between 2016 and 2020 – was forced to resign after fierce waves of protests erupted out of As-Suwayda. Protesters called for the removal of Al-Assad from power and for an end to the ever-worsening living conditions and corruption.

Additionally, protests were sparked again earlier last year. In February 2022, demonstrations led by religious elders were held in As-Suwayda, once again decrying corruption and the regime’s failure to address the declining economic condition and living standards.

And just last month, protests were again held. The image of Al-Assad was burned, a government building was ransacked and protesters clashed with police. As has become customary, the demonstration was met with violence – even among those protesting peacefully – and this even led to one protester, a young man named Murad al-Matni, being killed after being shot by security forces.

In fact, ever since Syria’s descent into a civil war, governmental security forces and their army have used excessive force to suppress protests which has led to the deaths of thousands. Undoubtedly, the rumblings of discontent directed towards Al-Assad’s regime has augmented steadily in the last decade, amounting to a society now that is fractured on all fronts; socially, politically and, especially, economically.

Even upon singularly examining As-Suwayda; 90% live below the poverty line, all local governmental aid has been ceased and there is a near-total power and fuel shortage; especially now during the cold winter months. All of this doesn’t even address the atmosphere of fear and intimidation that has further exacerbated civilian suffering.

Freedom of Expression Through Football

While some people may hold the quixotic view of viewing football as the manifestation of the white knight; unifying us all and reminding us to celebrate our commonality rather than standing principally on our differences. But it often doesn’t fulfill that role and can, quite often, produce the adverse effect.

In some cases though, it can serve as a reminder of what they are trying to unite for in spite of. In Syria’s case, any supporters trying to unite in support of football can be quickly rounded up and forced conscription. Additionally, as we know, the unity and organisation of football fan groups can be very effective anti-government protest models. The biggest example of this is Ultras Ah-Lawy, the main ultras group of Egyptian club Al-Ahly.

In 2011, when Hosni Mubarak’s reign in power in Egypt was finally snatched away as the power of the people truly had their voices heard. During Hosni Mubarak’s hegemony of Egypt, his notable policies – and the political legacy he patently left behind – included mass torture, arbitrary detentions, limitless censorship and, crucially, the cultivation of one of the most intimidating police states in world geopolitics.

Under a quarter of a century of this regime, the Egyptian people were extremely limited in the way that could participate in politics. And when a society can’t protest, can’t vote and can’t engender any kind of political discussion or debate, it is only natural to assume that unorthodox entities will emerge as a means to effectuate self-expression. Crucially, one of the biggest forms of this was through football, namely in the subculture of its Ultras. This, for many, became the structure in which their socio-political engagement was framed.

The main ultras group that influenced the revolutionary protests that toppled Mubarak though, was Ultras Ahlawy. As a group that separated from Al-Ahly traditional fan club (AFC) amid growing concern over the influence that the Al-Ahly board members had over the fan club, Ahlawy began by strictly voicing their fan-held principles against power.

For years, Ahlawy carpeted the faded greenery of Egypt’s pitches with crimson flares. They produced some of the most impressive tifo displays in world football, arranged and sang the lengthiest of songs for their club, rejoicing in their new-found status among the global Ultras subculture. However, the inevitable censorship they faced as a group – along with the prohibition of unorganized mass gatherings and the state’s willingness to silence unwanted political activity – shaped the group’s hostile and combative approach.

This, for an autocratic police state, is a logistical nightmare. Ahlawy presented the problem of invariable chaos whereby the state tried to respond to a subsect of predominantly young, politically outspoken men with no agenda other than the anarchic framework set by Ahlawy.

Amidst the chaos that was the Egyptian revolution in 2011, Hosni Mubarak’s reign was finally ended as the overwhelming outcry of his populous toppled his three-decade rule, dissolved the Egyptian parliament, effectively ripped up the nation’s constitution and football – chiefly its fanatical supporters – were right in the centre of it all.

A Tool to Highlight Suffering or End It?

When contemplating the logistics of Egypt’s revolution and the role that football and its ultras played, it is hard not to think about the potential football has to affect other nations. Football, and more holistically sports, can be used very effectively as an indicator of a country’s progression and developmental status and therefore, can be used to highlight political suffering.

In Syria’s case, it is slightly different because of the status of their civil war continuing on for so long and there is a sense for many people that there is no real end in sight. The dysfunction is an open wound at this point. It is so open for everybody to see but there is so much despondency and fear that has been instilled into people that resistance almost feels futile.

Syria haven’t played home matches in Syria for so long that any opportunities to organise fan protests or displays against authorities – that would have eyes guaranteed to see it – feel like a foreign concept. This season alone has underlined how fragile football in the backdrop of a civil war. The ongoing fuel crisis has immobilised the Syrian Premier League and halted any development that the league has had in recent years of getting back to what it once was.

Not since 2008 has a Syrian club qualified for the Asian Champions League group stage. However, it wasn’t long before that – 2006 – when Al-Karamah finished as runners-up in the ACL, narrowly missing out against Jeonbuk Motors in the final. Since then, the Syrian FA was suspended from entering clubs into the ACL and even now, despite their supremacy in the Premier League, Tishreen haven’t been able to compete in the ACL during in their golden age because of the difficulty of obtaining a license to play in the tournament.

Currently, Syrian football is in crisis and the fuel shortage has served to further highlight its fragility. For a country with a rich history of great players in Asia like Omar Al-Somah, Jehad Al-Hussain and Firas Al-Khatib, the country is now deprived of proper footballing development that had enabled the emergence of these players.

The ongoing status of the country’s football is one of misery and any successes feel like they are happening in spite of all the horrors draped behind it and examining the dysfunction of Syrian football is, basically, examining the dysfunction of a government and its economy. Football, as it is most of the time in these cases, just happens to be central to the ripple effect that this dysfunction has caused.

By: Louis Young / @FrontPostPod

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / EPA