What is Juego de Posición?

Juego de Posición refers to the distinct philosophy of play that Pep Guardiola uses in his teams. Translated to ‘Positional Play’, it is a philosophy that seeks to create an advantage over the opposition by a focus on the positioning and the movement of players to generate superiorities.

The philosophy originates from the Dutch school of football which was popularized by Johan Cruyff and was then adopted by pupils such as Pep Guardiola. There exist a lot of misconceptions on what positional play entails.

First of all, positional play is not the same as possession football – you can have a very successful possession-style football without positional play. Secondly, positional play doesn’t necessitate using the 4-3-3 formation. So What is Positional Play? Qué es el Juego De Posición?

As described above, it is a philosophy that revolves around certain principles. It is not a playing style, nor is it a system. The philosophy seeks to establish a possession-based game where the ball is advanced up the pitch by ensuring superiorities on each line and file.

Peak Pochettino: Analyzing the Tactics Behind Tottenham’s 2016/17 Season

The overriding objective of ‘el juego de posicion’ is to find, or create, the free man through using these superiorities but also by establishing a positional discipline among players. The concept of the free man refers to generating a situation where a player is “free” from any defenders – with time and space.

In effect, this means playing the ball to a player that can receive to turn and take two or more touches. The concept of the free man is the main concept of positional play and without it this model of play cannot function properly.

It serves two purposes: 1) To keep possession of the ball. By ensuring there is always a free man to play towards the team can always keep possession of the ball. 2) To penetrate lines.

Playing back to the goalkeeper may allow effective circulation of the ball but it rarely allows the team to advance up field into the opposition half. To successfully play forwards the free man must be found (or created) behind the line of pressure. The free man is generated through different methods:

- A common way of generating a free man is by having a player dribble with the ball in a dangerous area to attract defenders. Once the attacker has created an unfavorable 1v2 or 1v3 then the ball is released to the now unmarked players. Of course, the precondition here is that a player with great ability is required.

The Austrian Wunderteam: The Greatest Team You Don’t Know About

- Through the use of the third-man, a team can create or find the free man. A typical third-man pattern is to play a ball to the forwards who then bounce to an incoming teammate. The receiving player now has the ball facing forwards past the line of pressure.

- Lastly, the free man can be generated through the rotation and interchanging of positions. In midfield, coordinated rotation can allow players to find pockets of space to receive the ball facing forwards. Likewise, interchanging of positions can leave the opposition confused enough to surrender the necessary pockets of space.

All teams use the concept of the free man but the difference between a model of positional play and other models is that the concept of the free man forms the cornerstone of how a team advances forwards. If the free man cannot be found then the ball is circulated patiently at the back in order to create gaps.

Consequently, many coaches have sought to disrupt this by forming a defensive block against teams like Pep’s Guardiola or, very rarely, by invoking an intense man-to-man marking pressing style where there is no free man. Because teams prefer to defend with an extra player, there is usually always one free man, usually one of the centre-backs.

The different methods of generating or finding the free man can be categorized into three types of superiorities: numerical superiority, qualitative superiority, and positional superiority.

1) Numerical Superiority

The objective is to ensure an overload of players in the immediate vicinity of the ball-carrier. This allows multiple options of passes, facilitating the possession and circulation of the ball or a successful penetration from one line to another.

This numerical superiority is needed for build-up and is exemplified in tactical movements such as the ‘Salida Lavolpiana’. But numerical superiority is also sought in midfield as well as exemplified in Pep Guardiola’s inverted fullbacks, or the use of a false 9 to overload the midfield. There are many ways of achieving numerical superiority.

Tactical Analysis: Zinedine Zidane’s 2016/17 Real Madrid Side

The aim is to have numerical superiority wherever the ball is, whether in possession or not, and tactical arrangements differ depending on the opposition. This explains why the goalkeeper is pivotal to any team that attempts positional play as using the goalkeeper allows numerical superiority when playing out.

2) Qualitative Superiority

Not all players are equal and some situations favour one player over another. The objective is to create a 1v1 (or 2v2) situation in an area of the pitch where a player will have technical superiority over that of the opposition.

This means ensuring a team’s best players get the ball as often as possible and against the opposition’s worst players, while ensuring the opposition’s best players are denied the ball and are always up against the team’s best players.

For example, if you have a pacy winger, it is important to have him against one of the less pacy fullbacks in the opposing team. Another example is a player who is simply better in a 1v1 situation than the defender. The coach here looks to create situations where players will have an advantage over their marker.

3) Positional Superiority

Sometimes, even a player (and a team) of lesser quality than the opposing one will triumph due to the amount of space and time that player is afforded. The objective here is to create as much space between the lines and files for the players to exploit.

By ensuring players take up set positions and undertake certain movements a team can gradually move up to attack regardless of how defensive an opposing team may be. Of fundamental importance is creating the necessary width and length needed.

A player may not be that quick but if the team can generate large gaps to stretch the opposing defense the defender will struggle against even a slow forward. Likewise, a player not very good at defending may appear solid at the back if the team remains compact and the area the player is asked to defend is quite small.

Simone Inzaghi’s 3-5-2: Inter Milan 2021/22 Tactical Analysis

A good example is Pep Guardiola whose defensive capabilities as a holding midfielder were questioned when he first emerged in Johan Cruyff’s team. Johan admitted as much but merely told Pep Guardiola to defend the space in front of the two centre-backs, and to avoid being dragged wide or high.

The Grid of Positional Play

While most teams may use these three strategies to create superiority, the philosophy of positional play has a much greater emphasis on positional discipline which can make the system appear too rigid.

Commentators have criticized managers like Louis van Gaal for the amount of restrictiveness imposed on players which curtails their freedom of movement and makes their tasks overly repetitive.

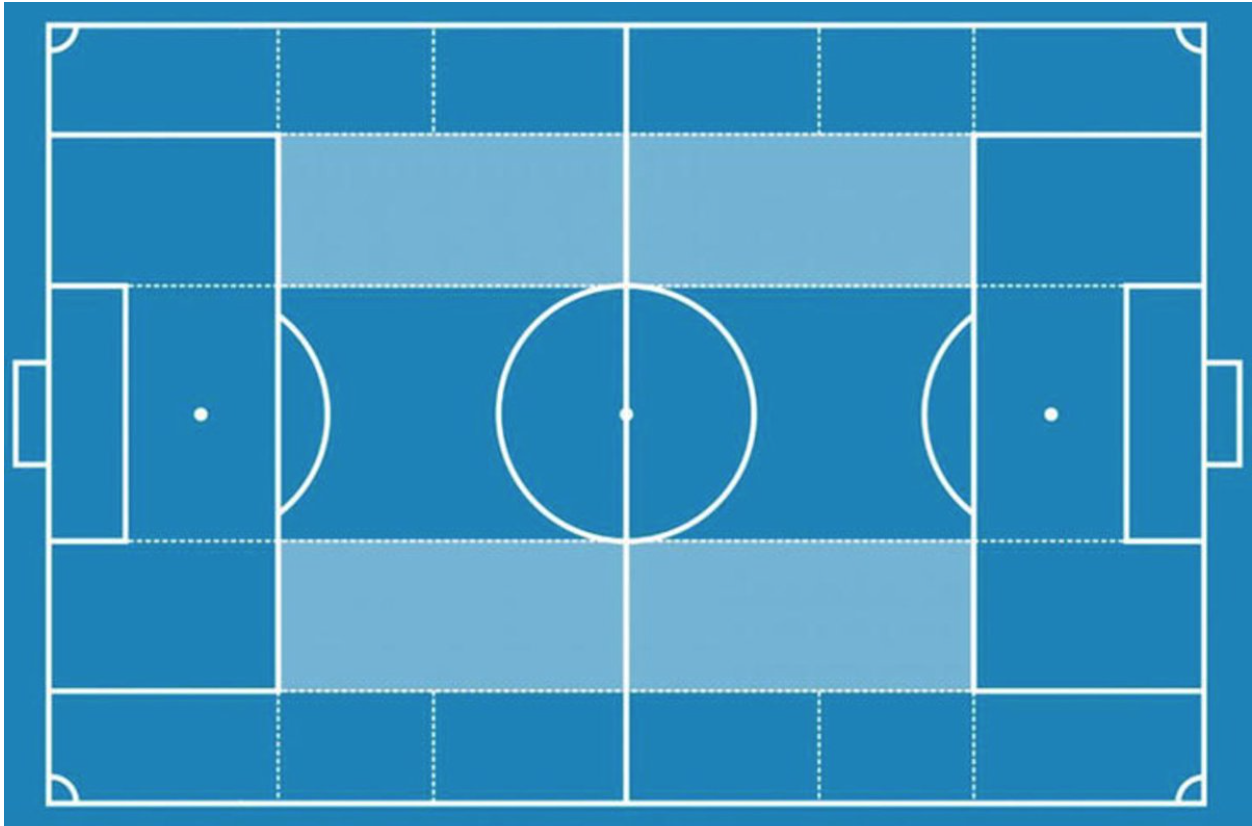

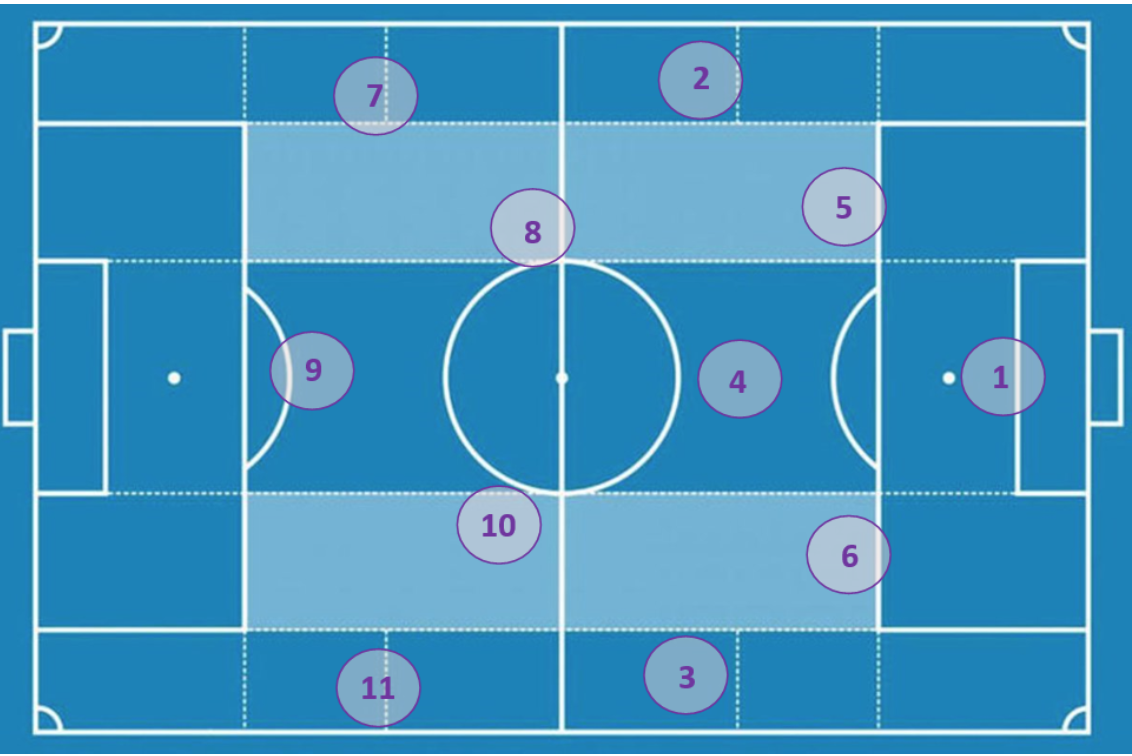

Supporters of positional play divide the pitch into certain zones to give players better understanding of their position and movements. The pitch below is a representation of what Pep Guardiola likes to work with.

It has a middle zone flanked by two half-spaces and the wings are divided into many smaller zones. It also has two penalty boxes. In positional play, the half-space on each side is given certain priority because it is where the greatest danger originates from.

The division of the field into grids is meant to be used as a reference point to impose positional discipline and movements. Thus, certain rules must be abided by.

The first rule is that players are instructed to maintain a maximum of two players at any zone vertically and a maximum of three players at any horizontal line. Ideally, each zone out wide should only have one player occupying them whenever possible.

This strict positioning of players ensures that the team creates as much width and length as possible, creating gaps in the opposition defense, and generating as many 1v1 situations across the pitch. As the team pushes up each player occupies a new zone.

Conventional positional play assigns zones to each position. For example, the middle zone should be occupied only by the centre-forward (#9) and the holding midfielder (#6) for most of the game. As can be seen in the diagram above, each area has no more than 2 players and any extra player entering such areas would lead to an imbalance.

This brings us to the second rule which ignores this rigidness when the purpose is to ensure possession (create triangles), generate overloads, or lure defenders out. Thus, a zone may have more than 2 players if it accomplishes these objectives. However, these movements should only be temporary and once the objective is achieved, players must return to their zones.

The third rule is that the ball should not be played inside the same zone but should be circulated from zone to zone whenever possible. Not following this rule will lead to dispossession so if the zone becomes too congested the ball should be played out of it quickly.

As can be seen, playing a vertical pass within the half-spaces or middle zone is unlikely to succeed. Diagonal passes are therefore encouraged when going forwards as opposed to vertical passes such as a pass from the half-space to the middle zone and vice-versa.

Guardiola uses a pitch with these zones marked out at training to enforce these rules. However, it seems that these rules are only used prior to reaching the final third – upon arriving at the final third the players are allowed to express themselves.

This isn’t the only way Guardiola divides the pitch though. Thierry Henry noted that Guardiola used to occasionally divide the field in two and force half the team to play on one side and the other on the other half. During matches, players were forbidden to move from their position under the punishment of being benched.

This ensured players created the necessary width and forced the midfielders to split up rather than be too close to each other. As can be observed, the formation 4-3-3 shown above facilitates the distribution of the players into their zones which explains why it is preferred to other formations – but it is not a requirement.

By: @YouthPreview

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / David Ramos – AFP