The Rise and Fall of Parma

Football in Parma is a story of a club propelled from decades of lower league football to a few short years of top-flight status and multiple European trophies – before financial ruin left them trying to sell those very same trophies to stay in business.

Correlations between financial crises and Italian clubs have always been present with one of the more stark cases being the incredible rise and then sharp fall of Parma. Possibly one of the most extreme rises and falls, the nineties brought previously unseen glories to the northern-based city before quickly vanishing back to levels more typical.

In their club history that stretches back for over a century, much of that time had been spent in the lower leagues of Italian football. However, in the space of four years, they went from being an unremarkable lower-league side to a continental force.

A founding member of both Serie B (in 1929) and Serie C (in 1935), Parma spent years changing through these two divisions, early connoisseurs of the ‘yo-yo’ team tag perhaps, before relegation in 1966 saw them drop to Serie D.

The Rise & Fall of Palermo: World Cup Winners, Cult Heroes and Financial Ruin

This fall to Serie D was soon met with financial woes and liquidation, in 1968, which saw the original football club of Parma have their sporting licence taken on by A.C. Parmense. The years following this once again saw promotions and relegations, before settling as mainstays of Serie C.

Long-term mediocrity began to subside around the mid-1980s when a sustained period in the second tier was achieved and, in 1986, victory over the supreme AC Milan, an obvious high point creating great euphoria. Manager Arrigo Sacchi, in his three years at Parma, came close to delivering Serie A status before moving on to glory with AC Milan.

It was Nevio Scala in 1989 who, in his first season of managing Parma, led the club to promotion to the top flight for the first time on club record and kickstarted a change in the history of I Gialloblu.

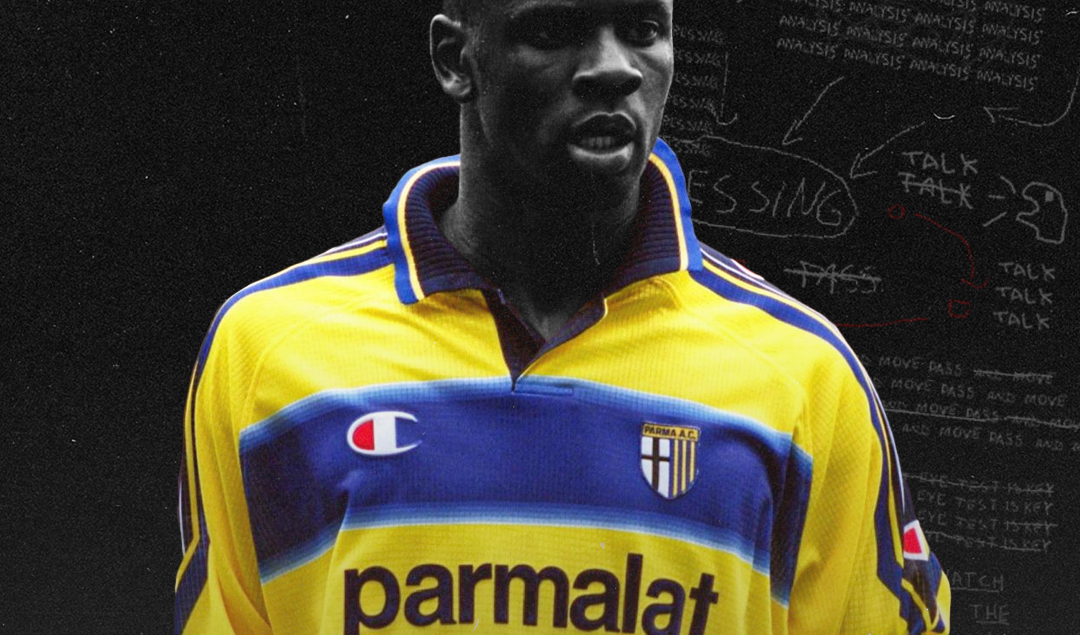

With new and wealthier ownership also coming in 1990, the turn of the decade brought hope, glory and riches that saw Parma become recognised around the world with squads filled with future Calcio cult heroes in the distinctive, unmistakable yellow and blue kits. The city, from the northern region of Emilia-Romagna, has long been famed globally for its ham and cheese – from the 90s it also became known for its football.

Parma’s rise was, quite simply, remarkable. Owning 98% of the club, Parmalat, the dairy and food company whose name was emblazoned across the most well-known Parma shirts, poured large amounts of money into the club and, through this investment, enabled the side to compete at such high levels. Similarities between Parmalat and Red Bull’s approach twenty years later are striking.

Of note, however, is that Scala was determined to develop and bring through youth players, with one notable example being Gianluigi Buffon. This policy was seen through the signings made and also, targeting young talents with strong financial backing, players such as Fabio Cannavaro, Dino Baggio and Faustino Asprilla to name just a few.

In their debut top-flight season, Scala guided Parma to a sixth-place finish and qualification for the UEFA Cup. Often deploying five defenders, Parma conceded the joint fourth lowest number of goals for the entire season. Although, their lack of goals scored is equally notable, even though they achieved such a high finish in the table.

CEO of Parmalat, Calisto Tanzi, continued to pour money into the club to push Parma towards trophies and to show his continued support of Scala. Fortunately for Tanzi, this wait for silverware was not long at all as Parma went on to beat Juventus 2-1 on aggregate to claim the 1992 Coppa Italia.

Though there was no improvement made on the league position in Parma’s second-ever Serie A season, and they bowed out of the UEFA Cup in the first round, winning the domestic cup allowed for qualification for the 1992-93 UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup.

The 1992-93 season saw the arrival of Asprilla from Atlético Nacional, making a significant impact on the season. It was the Colombian’s free-kick that defeated AC Milan 1-0 and brought to an end to I Rossoneri’s 58-game unbeaten run under the management of Fabio Capello and captained by Franco Baresi.

Asprilla’s involvement went further, with him putting two past Atlético Madrid in the Cup Winners’ Cup semi-final – taking Parma through to the final where they beat Royal Antwerp 3-1, even though Asprilla was bound to the bench with an injury.

It had been a meteoric and spectacular rise for I Crociati (The Crusaders) as in the space of just four years they had become a serious European power. Obviously, the financing propelled Parma to the spotlight, but Scala’s tactics and smart recruitment of players backed up the fees being spent.

European success had been achieved and, for Tanzi at least, all focus was placed upon winning the Scudetto. In the early years of Parma’s rise, the defence was always strong but the attack struggled to score the goals necessary to challenge for the title. Scala addressed this at the beginning of the 1993/94 season by adding Gianfranco Zola to a forward line that already contained the creative and elusive Asprilla.

The season didn’t pan out so successfully, however. More goals were scored and roughly the same conceded, but this was the year where Milan won the title letting in only an astounding 15 goals across 34 games – difficult for most to match.

This resulted in a drop in the league table from 3rd to 5th and although Parma managed to reach the final of the Cup Winners’ Cup again, the run ended in defeat to Arsenal. They’d have to settle for victory in the European Super Cup over Milan instead.

Quite simply, Parma had already begun to take Europe by storm and had disrupted the original footballing giants of northern Italy by pushing themselves in and challenging for the title. In the immediate years that followed the theme of being successful in Europe continued – winning the UEFA Cup Final against Juventus in 1995 and then again in 1999 after easing aside Marseille.

The Rise and Fall of Bernard Tapie’s Marseille: Part 6: Le Mec de La Courneuve

After first entering a European competition in 1991, within eight years they had four trophies to their name. But it was the Scudetto that still haunted Tanzi and after the 1995-96 campaign went awry, a trophyless season and a sixth-placed season, Scala left the club after a whirlwind seven years in charge.

And it was Carlo Ancelotti who was to inherit this side and dealt with the outgoings of Hristo Stoichkov, Filippo Inzaghi, Zola and Asprilla by bringing in Lilian Thuram, Enrico Chiesa and Crespo. Truth be told, the signing of 29-year-old Stoichkov the previous summer for just under £10 million was an outlier in how Parma usually conducted their transfer business and so replacing him with Crespo for around £4 million – who’d later be sold for a world record fee of £35 million – was more typical of the Parmalat-financed side.

In Ancelotti’s first season, Parma missed out on the Scudetto by a mere two points with Crespo and Chiesa scoring 26 of the 41 league goals and Buffon, Thuram, Cannavaro and co. keeping together a rock-steady defence. The season that followed would also be without silverware and with a tense relationship between owner and manager, Ancelotti was replaced with Alberto Malesani.

Malesani’s impact was instant and profound with Parma having arguably their finest season – winners of the Coppa Italia and UEFA Cup. Crespo continued to fire them in and they now had a squad containing reliable, uber-talented performers.

By the end of the decade, multiple trophies had been claimed, millions had been spent and received, and international recognition was achieved. However, the failure to ever win the league title with the players at hand will always be a disappointment.

At the turn of the millennium, all of the adulations of the decade just gone were soon to be dashed. Though cult heroes such as Adriano and Hidetoshi Nakata continued to crop up and steal the hearts of the Parma faithful, the quest for a Scudetto became more unrealistic year by year, even after success in the Coppa Italia in 2002.

Midway through the 2003/04 season, Parmalat, the company effectively controlling Parma, went out of business with it being revealed they were €14 billion in debt – still the largest bankruptcy Europe has witnessed. The sales of key players did not remedy this and so Parma tumbled down Serie A until relegation in 2008, ending an 18-year top-flight stretch.

They did play European football in their penultimate Serie A season, due to teams that were involved in Calciopoli being docked points. To date, Parma have not competed in Europe since, such a dramatic fall for the once ‘Crusaders of Europe’.

Following relegation, a return to the top division was quickly secured and a run of mid-table finishes became the norm until a sixth-placed finish in 2013/14 meant European football was back on the cards. However, their late payments of income tax on wages barred them from qualifying for a UEFA licence and so they were not allowed to compete in the UEFA Cup, whilst points were also docked for the following campaign.

This next season saw more financial meltdown and Parma went bankrupt in 2015 and even attempted to raise some cash via the sales of all their European trophies from the 1990s and domestic ones too. How dramatic that the very trophies they had fought so long and hard to win were now being touted for sale in order simply to survive.

Livorno: A City with a Proud History but an Uncertain Football Future

Since being refounded in 2015 under S.S.D. Parma Calcio 1913, back-to-back-to-back promotions amazingly managed to see the side competing back in Serie A just three years after insolvency – until relegation again struck in 2021.

In January 2020, Parma’s owner became American billionaire and convenience store businessman, Kyle Krause, although his arrival has only led to relegation and mid-table Serie B finishes. So, it will be interesting to see whether Parma revert back to being a club just existing in the second tier, or fight their way back to Serie A. Though no longer competing weekly with the likes of Juventus and the Milan clubs, support remains solid at the Stadio Ennio Tardini.

Whatever the future, their astounding rise during the 1990s, seemingly out of nowhere, to unsettle the footballing giants will always be vividly remembered despite the scandals that reset their history a decade after it all began.

By: Thomas Shelton / @tomshelton11

Featured Image: @GabFoligno / Neal Simpson – EMPICS / PA Images