The 10 Greatest Teams Who Failed to Win a World Cup

During the weeks and months leading up to the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022, we will drop a weekly article that chronicles the history of the most prestigious football tournament on the planet. This series of articles will also allow you, the readers, to revisit all 21 previous editions from different angles and perspectives. We also hope these review pieces will help build up expectations and excitement for the upcoming tournament. Therefore, without further ado, we present to you the first installment of the series.

We call them “Unfinished Symphonies” or “Beautiful Losers”. What skeptics see as flaws and failure we gloss over as originality and innovation. We make up excuses to explain away their shortcomings and we use the aforementioned euphemisms to refer to them because we subconsciously cannot bear the harsh truth that they lost the crown jewel and collapsed at the most crucial moment of the tournament.

Some of them are even more talked about, heralded, and even written about than the team that beat them or won the tournament. One of the reasons they conquered our hearts and minds is unmistakably because they boasted some of the most iconic players to ever grace a football pitch.

In addition, they were built by visionary, bold, and charismatic coaches who etched their names in the history of the game. But, above all else, these teams changed the game forever and for this reason, we like to think of them as pioneering trailblazers both revolutionary and transcendental.

10. Portugal 1966

Coach: Otto Glória

Achievements: 4th place World Cup 1966

Key Players: Eusébio, Mário Coluna, António Simões

Star Player: Eusébio

Formation: 4-1-3-2

Legacy: First major footballing achievement for Portugal

The first question that may come to mind is, “Why a first-timer?” I would argue that this team was used to the big stage long before setting foot in England for the World Cup since it was built around the core of the historic early 60s Benfica side that put an end to the hegemony of Real Madrid in the fledgling European Champions Cup under the tutelage of legendary Hungarian coach Béla Guttmann.

Players like Mário Coluna, António Simões, or José Torres were already household names while Eusébio was none other than the outright second-best player in the world and reigning Ballon d’Or winner.

The Portuguese were drawn into a difficult group with the two-time defending champions Brazil led by Pelé, the undisputed number one player in the world at the moment, Bulgaria and Hungary. They did light work of the opposition by scoring three goals past each opponent in the group stage while collecting all six points.

Boavista and Os Belenenses: The Glorious Exceptions to Portuguese Football’s Oldest Rule

Next, the Otto Glória-coached team faced a resilient North Korean team in the quarter-finals. Unexpectedly, the Koreans led 3-0 after only 25 minutes of play. Ultimately, the Portuguese won the game 5-3 after Eusébio scored a quadruple. The native of Mozambique would finish as the top scorer of the tournament with nine goals.

In the semifinal, Portugal was initially set up to play the hosts, England, at Goodison Park in Liverpool. However, after persistent and intense pressure from the English Football Association to take the game to London FIFA gave in to the request.

On the day of the match, the Portuguese had to travel from Liverpool to London by bus only to find a well-rested English team already present in London waiting for them. Fatigue would eventually play a non-negligible role in this semifinal. With more than 100,000 fans in the stands, the Three Lions defeated Portugal 2-1, in a game marred by a small controversy.

While down 0-2 to the British, Eusébio would cut the lead in half after converting a penalty at the end of the game. However, Jack Charlton should have been booked and even sent off for having deliberately handed the ball back on his line. A red card might have changed the (mis-)fortune of this valiant team.

9. Croatia 1998

Coach: Miroslav Blažević

Achievements: Semifinalist Euro 96, 3rd place World Cup 1998

Key Players: Davor Šuker, Zvonimir Boban, Robert Prosinečki, Robert Jarni

Star Player: Davor Suker

Formation: 3-5-2

Legacy: The Vatreni provides hope to a new, war-torn nation

After the Balkan Civil War (1991-1995), which left more than 20,000 dead and 500,000 displaced among the different populations, Croatia, like several Slavic states, split from former Yugoslavia to claim independence.

This geopolitical realignment also led to a new balance of power in the world of football. Most of the most talented players who constituted the Yugoslavian team came from Croatia with Dinamo Zagreb being the main provider.

Led by manager Miroslav Blazevic, the golden generation of Croatian football stunned the world two years prior at Euro 1996 when they reached the semifinals while showcasing some of the finest collective displays during the tournament. The World Cup in France was therefore an opportunity to show their stellar European Championship run wasn’t a fluke.

Among their top players were Davor Šuker (Real Madrid), Zvonimir Boban (AC Milan), and Aljoša Asanović (Naples). The fact that Robert Prosinečki, Boban, Šuker, and Igor Štimac were world champions under 20 with Yugoslavia in 1987 also meant this team’s core had been playing together for more than a decade.

The Croatians had an almost flawless group stage with wins against Jamaica (3-1), Japan (1-0), and a narrow defeat against Argentina (0-1). In the round of 16, they defeated Romania (1-0). Their most impressive display would come against the reigning European champions Germany (3-0) whom they thrashed with style and authority.

Robert Jarni and Goran Vlaović scored the first two almost similar goals before the tournament’s top scorer and team star Šuker sealed the win. In the semifinal, they led 1-0 against the hosts and eventual world champions France before conceding two goals to the most unlikely individual, Lilian Thuram.

Despite the defeat, the Croatian dream does not end in the semi-final against France. It would continue into the third-place game against the Netherlands (2-1). The words of Blažević demonstrated the deep joy of the Croats after this third place. “The Croats needed a light, and the light was the selection.”

8. Soviet Union 1986

Coach: Valery Lobanovskyi

Achievements: Semifinalist World Cup 1986

Key Players: Igor Belanov, Oleg Blokhin, Rinat Dasaev, Vasily Rats

Star Player: Igor Belanov

Formation: 3-5-2

Legacy: Total Football with a Russian twist

Just like Isaac Newton gets most of the credit for having invented calculus although Leibniz had discovered that same branch of mathematics around the same time, Rinus Michels’ name is widely and generally associated with Total Football although Lobanovskyi came up with the same tenants and principles at Dynamo Kyiv almost simultaneously.

The quizzical Ukrainian coach would manage each of his home club Dynamo Kyiv and the national team during multiple spells. However, in 1986, he was busy with both teams. After winning the European Cup Winners’ Cup with Dynamo Kyiv, he took the reins of the national team for the World Cup in Mexico.

It was only logical that he selected nine of his eleven players from his beloved Dynamo Kyiv. Among these talented players, the Lobanovski counted mainly on quick and deadly striker Igor Belanov, a dynamic winger named Alexander Zavarov, as well as a world-class goalkeeper with immense qualities going by the name of Rinat Dassaiev, who proved to be almost unbeatable when the attackers try to beat him with aerial and ground strikes.

The football advocated by Lobanovski is precise, fast, and all in motion. Done well, it can drive the tightest defenses crazy. He insisted that his players should not think in terms of defenders, midfielders, or attackers as they should all be versatile enough to occupy different positions with the same effectiveness.

At the 1986 FIFA World Cup, the USSR was drawn into Group C with Hungary, France, and Canada. The first round of the event revealed a conquering Soviet team who demolished the Hungarians (6-0) and Canadians and made only one misstep in the form of a draw against the French. After group play, a fair amount of pundits began to see them as surprising and legitimate contenders.

The Soviets topped the group with five points, just pipping France for the top spot on goal difference. The Soviet Union was scheduled to face Guy Thys’s Belgium in the last sixteen of the knockout phase.

In an electrifying and memorable encounter under the bright sun at the Estadio Nou Camp, in Leon, Belanov drew first blood by stunning Jean-Marie Pfaff with a powerful shot to give the Soviets an early lead. As the first half was closing to an end, he unluckily headed a cross on a post. The Belgians felt lucky to go into halftime with only a one-goal deficit.

After the break, Belgium would equalize on a beautiful goal from Enzo Scifo. In the 70th minute, Belanov found himself again in scoring position and did not waver. With a 2-1 lead, the Soviets – who had been the superior side so far – were contemplating victory. However, Jan Ceulemans had other plans.

The Rise & Fall of Palermo: World Cup Winners, Cult Heroes and Financial Ruin

After receiving a long ball from Patrick Vervoort with seven minutes remaining in regulation, he broke free of the Soviet defense to level the score (2-2). The Soviets made a costly error by playing for a high line for an offside trap that failed miserably, and Ceulemans coolly scored the goal that sent the match into extra time.

The Soviets felt wronged by the referee’s decision to not sanction an offside violation on Belgium’s second goal. Yet the worse was to come for them. The Belgians would draw first blood in extra time as Stéphane Demol would put them ahead with a winning header that left no chance for Dassaiev (3-2). Furthermore, Nico Claesen would give the Belgians a decisive two-goal cushion by scoring a fourth goal (4-2).

Down two goals, the Soviets regrouped, regained composure, and began looking for an equalizer after Belanov successfully cut the deficit to one goal on a calmly converted penalty kick (4-3). The Soviets gave it all on the pitch but were denied what would have been an equalizer by the heroics of Jean-Marie Pfaff.

Belgium would hold off the courageous Soviet side and move to the next round while the latter would bow out of the tournament. After the game, Soviet coach Valery Lobanovskyi acknowledged the quality of the game while bemoaning the result. “That was one of the most fervent games we’ve seen at these finals,” he said. He added, “It was a great spectacle, although the Belgians’ second goal was offside.”

7. Netherlands 1998

Coach: Guus Hiddink

Achievements: Semifinalist Euro 2000 and World Cup 1998

Key Players: Dennis Bergkamp, Patrick Kluivert, Edgar Davids, Marc Overmars

Star Player: Dennis Bergkamp

Formation: 4-4-2

Legacy: The last golden generation of Dutch football

This generation of Dutch football boasted some of the finest players of their era: Dennis Bergkamp, the Non-Flying Dutchman viewed as one of the best players in the world, or the likes of Patrick Kluivert, Marc Overmars, Edgar Davids, Clarence Seedorf, Frank De Boer, Jaap Stam were called up by talisman Guus Hiddink for France 98.

As the top seed of Group E, Holland was drawn with Belgium, Mexico, and South Korea. The Dutch were in excellent form after defeating their opponents 7-2 in the opening round and taking first place in the group, but on June 25 at St. Etienne, they would draw 2-2 with a shaky Mexican team.

The game between Mexico and Holland ended up being the most thrilling of the bunch. Phillip Cocu gave the Dutch the lead after four minutes, while Ronald de Boer doubled their advantage a few minutes later. However, Mexico staged an incredible comeback late in the second half, cutting the lead in half with Ricardo Palaez in the 75th minute to 2-1, and then tying it with Luis Hernandez in stoppage time (2-2).

Tension at the Tail-end – The Crazy Conclusion to the 2001/02 European Football Season

Edgar Davids’ injury-time goal gave Holland a 2-1 victory over Yugoslavia in the 92nd minute. With his goal, Davids was able to atone for his previous falling out with Dutch manager Guus Hiddink because he criticized the technician after Holland’s dismal performance at Euro 1996.

In the quarterfinal, Holland came out victorious (2-1) in an epic encounter against Argentina which will forever be remembered for Dennis Bergkamp’s masterclass punctuated by a mesmerizing and spectacular goal in extra time.

The Non-Flying Dutchman expertly collected a Frank de Boer’s 60-yard pass, got the ball to his feet, bamboozled defender Roberto Ayala in the box, and fired a shot beyond Roa. That earned them a date with Brazil in the semifinals.

The showdown in Marseille was enthralling; the Netherlands going against Brazil, two masters of open football were duking it out for a ticket for the greatest show on Earth, the World Cup Final. The game began more cautiously than one might have expected: two heavyweights sparring, searching constantly for the opportunity to strike, fearful always of an opponent’s counter while both Bergkamp and Ronaldo remained firmly shackled.

For Holland, Edgar Davids chose this night to leave an indelible impression on all spectators. Seeming inexhaustible, fearless in the tackle, his inspiration gave the Dutch an edge for most of the evening. Kluivert came close to opening the score twice with a couple of headers while Ronaldo, hounded and harassed, could only watch, envious of the service from the other end.

If the first half was almost uneventful, the second instantly exploded into life. Rivaldo from the kick-off picked out Ronaldo, who beat Edwin Van Der Sar with ease. Dominant thus far, Holland was behind, punished for their lack of concentration. Frank De Boer almost brought them level: arriving to meet Kluivert’s neatly flicked header, he volleyed fiercely.

Claudio Taffarel extended to keep a clean sheet and Roberto Carlos, reacting the quickest, cleared the loose ball. On the 64th minute mark, Ronaldo hit a powerful shot towards the Dutch goal only to be denied by Van Der Sar, and then as Bebeto moved in on the loose ball, the big goalkeeper frustrated him. Another ten minutes and Ronaldo broke free again. This time it was the wonderful, energetic Davids who dispossessed him.

Significantly though, as Holland’s need for an equalizer grew desperate, Brazil had wrested control of the game. Twelve minutes from the end of regulation, Rivaldo had a golden chance to settle it. Denilson swept by Aron Winter and whipped in a cross. However, because of his tangled legs, Rivaldo was unable to control the ball properly, and his shot from only six yards was unable to trouble Van Der Sar.

It would be another eight minutes, four from the end before his error would be compounded, Ronald De Boer delivering a cross, and Kluivert taking full advantage of slack marking to beat Taffarel at his near post. In extra time, as hard as both teams tried, there were no further goals. Ronaldo might have twice won it for the Brazilians but Kluivert came closest of all with a drive that shaved Taffarel’s goalpost.

Cruelly, it would be the pain of elimination by a penalty shoot-out, and indeed De Boer stepped forward to take his team’s fourth, the equation was simple: score or go home. Despite being under such intolerable pressure, and hitting his shot firmly, it was within the reach of Taffarel, and Brazil was through.

Hiddink, the devastated Dutch coach, praised his team’s courage and commitment, refusing to discuss contributory reasons for the defeat. ‘I do not search for excuses in the injuries and suspensions that affected team selection,’ he said.

6. France 1982

Coach: Henri Michel

Achievements: Winners of Euro 84, Semifinalists World Cup 1982, Semifinalists World Cup 1986

Key Players: Michel Platini, Jean Tigana, Luiz Fernandez, Alain Giresse, Marius Tresor, Dominique Rocheteau

Star Player: Michel Platini

Formation: 4-4-2 (Diamond)

Legacy: Romanticism in football

Heralded as the finest generation in French football history, the 1982 version of Les Bleus, perhaps hindered by the weight of expectations, did not start their World Cup campaign in glowing fashion in San Mamés as they were convincingly defeated by a solid English team (1-3).

Their shaky start to the tournament would continue despite the fact they would rout Kuwait (4-1) at the end of a match marred by a surreal incident where a Kuwaiti sheik would step on the pitch to ask for a French goal to be disallowed. They would struggle to earn a point from a difficult draw against Czechoslovakia (1-1) before qualifying to the wire for the second round.

A favorable draw for the second round would pair them with Austria and Northern Ireland in Group D. As the tournament was playing out, Les Bleus suddenly found their mark against a valiant Austrian side. The Austrians felt optimistic for having previously beaten France eight times in fifteen games (one draw).

The French team dominated the match from start to finish while using their sharp movement and vivacity against a heavy and slow opponent, and showing their rational tactical guile, speed of execution with one-touch play, and creativity produced primarily by their “magical midfield” composed of Jean Tigana, Alain Giresse, Bernard Genghini, Michel Platini. France’s winning goal would come from a twenty-five meters masterpiece of a free kick from Genghini that left Austrian goalkeeper Freidrich Koncilia stunned.

A double brace from Dominique Rocheteau and Alain Giresse will help the French team see off an unmatched Northern Ireland team (4-1) and win Les Bleus a date with West Germany in the semifinals. That semifinal would be one of the most beautiful matches in the history of the World Cup and the pride, for the French players, of having shown the world what they could do, of having written a page in the legend of football.

Le Carre Magique: The Story of France’s Golden Midfield Quartet

Platini and Giresse who were closely man-marked by respectively Wolfgang Dremmler and Paul Breitner gave the Germans all they could handle by carving out spacing their defense for Didier Six and Dominique Rocheteau to thrive. However, West Germany would open the score against the run of play when Pierre Littbarski converted a rebound after Jean-Luc Ettori had trouble securing Breitner’s tricky but heavy shot.

Platini would equalize from the penalty spot after Bernd Förster clumsily pushed Rocheteau in the German box. Then the unexplainable would occur as substitute Patrick Battiston was launched on the break by an exquisite pass from Giresse with a clear goal-scoring opportunity, he was violent kicked down in the torso by Harald Schumacher who had no other intention but to harm the French forward.

Battiston was so severely harmed that his case required oxygen and he had to be rushed out of the pitch to the hospital. The fact that the referee did not even punish the German goalkeeper, nor even awarded a foul for the blatant assault on the French player only added insult to injury to the discontent of the French team and the dismay of spectators worldwide.

As the game went to extra-time, the French finally saw the fruit of their domination rewarded. Tresor would score on a beautiful setup by Giresse (2-1) and Giresse himself will give the French a two-goal lead a short while after with a beautiful finish (3-1).

When all hope seemed to be lost, the resilient Germans came back to life behind a goal by hobbled super substitute Karl-Heinz Rummenigge (3-2). The Germans would complete the comeback six minutes later with an equalizer from Fischer that left the French team stunned and heartbroken. They would never recover as they would lose in the penalty shootout.

Les Bleus suffered a painful heartbreak as they were the better and most creative side for most of the game and yet endured elimination to a pragmatic, resourceful and robust West German side.

5. Argentina 1930

Coach: Francisco Olazar

Achievements: Runner-ups Olympics 1928, Runner-ups World Cup 1930

Key Players: Guillermo Stabile, Luis Monti, Carlos Peucelle

Star Player: Guillermo Stabile

Formation: 2-3-5

Legacy: Individualism over collectivism

The Argentine team of the late 1920s and early 1930s won the hearts of fans around the world during the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam and at the 1930 World Cup in Uruguay with their mesmerizing individual brilliance and elegance. Nonetheless, they came up short in the final both at the Olympics and the World Cup at the hands of their arch nemesis: Uruguay.

Argentina beat France in their opening match on a late strike by their charismatic captain Luis Monti. They moved on to thrash Mexico and Chile in their second and third games in the group stage 6-3, 3-1 respectively with a haul of five goals from Guillermo Stábile who would end up as the tournament’s top scorer. In the semifinal, they eased past the United States 6-1 with a double brace from Stabile and Carlos Peucelle while Alejandro Scopelli and Monti added two more goals.

The Rise and Fall of Bernard Tapie’s Marseille: Part 1: L’homme d’affaires

The final, on July 30th, 1930, would pit the upstart Argentinean team against the hosts, the formidable and two-time defending Olympic champion Uruguayan. Scheduled to be played in the newly inaugurated Centenario stadium, with a capacity of one hundred thousand people, the Argentinean press billed the final as the most significant match in the history of the Albiceleste to date. Yet they lost it in controversial situations, which favored the locals, as Uruguay, as a nation treated the game as if it were a war.

“The Uruguayans have made war on us since we arrived because they knew that the title was going to be between them and us. At night they wouldn’t let us sleep and they insulted us in training”, recalled Francisco “Pancho” Varallo years later. Monti and other Argentine players received death threats the night before the match. Their families were allegedly monitored by two Italian spies from Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime.

Monti himself, who after the World Cup was recruited by Mussolini for the Italian national team, said years later “When we came back to play the second half there were about three hundred soldiers with fixed bayonets. They were not able to defend us.” Many Argentine players feared for their lives as they headed into halftime of the World Cup final with a 2-1 lead over Uruguay.

On top of the harassment suffered by the Argentine players, another controversy started about the ball with which the match would be contested. As there was no official ball, both captains came to the draw to impose their own.

The Belgian referee Jean Langenus threw a coin in the air. This decision determined the first half would be played with the Argentine ball and the second, with the Uruguayan one. Therefore, each team ended up winning the “time” that was played with its favorite ball.

The Uruguayans would come from behind to beat the Argentineans 4-2 and cement their domination of world football with the Jules Rimet Cup after two consecutive Olympic gold medals.

4. Austria 1934

Coach: Hugo Meisl

Achievements: Winners of the Central European International Cup 1933

Key Players: Matthias Sindelar, Josef Bican, Anton Schall, Josef Smistik

Star Player: Matthias Sindelar

Formation: 2-3-5

Legacy: Precursors of Total Football

In May 1931, Austria became the first team outside the United Kingdom to beat Scotland 5-0. This singular event marked the birth of the Wunderteam. From this moment, this majestic and very skillful side would lose only two games in 3 years and revolutionize football.

It was journeyman Jimmy Hogan who laid the foundation of what would be called the “Danube School” by instilling into Austrian football the principles of the Scottish way of play. Following in Hogan’s footsteps, the ambitious Hugo Meisl expanded on the theory of quick and short passing with a huge emphasis on technique rather than physicality.

The Austrian Wunderteam: The Greatest Team You Don’t Know About

He also created both fluid and dynamic front 5 in which the forwards would change positions interchangeably. Such finely choreographed player movement was harnessed into a team structure. It also necessitated skillful players like Matthias Sindelar and Josef Bican who were at the heart of the team. Sindelar, the most iconic member of the team, was a magnificent dribbler, and justly considered the most talented player in the world at that time.

After winning the Central European International Cup (the forerunner to the European Championship) by scoring 29 goals while only conceding 4 in 5 games against prestigious opponents like Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, and Italy, they embarked on a streak of 14 consecutive wins right before the 1934 World Cup in Italy ruled at the time by Mussolini’s fascist regime.

Rightfully, Austria was viewed as the overwhelming favorite upon entering the tournament. They would win their first two knockout games against two very tough opponents in France (3-2) and Hungary (2-1) in respectively the round of 16 and the quarterfinals before facing the hosts, Italy, in the semi-final.

They would lose in the semi-final against Italy in a particularly stormy match stained by both malevolence and irregularities. Argentine defender, Luis Monti, who was known as the most brutal and wicked defender of his time, playing for Italy, deliberately injured Sindelar during the game.

Since red cards and substitutions did not exist at the time, Austria will lose 1-0 ending the game with a serious handicap with only nine players against eleven. To make matters worse, some actions were worthy of a comic film: the Italian goal would be scored by three Azzurri players who charged irregularly the Austrian goalkeeper while pushing him to the ground under the complicit eye of the Swedish referee.

3. Brazil 1982

Coach: Tele Santana

Achievements: Winners of Mondialito 1981

Key Players: Zico, Falcao, Socrates, Torinho Cerezo

Star Player: Zico

Formation: 4-4-2

Legacy: The last tenants of “Jogo Bonito”

What is the ultimate purpose of football? Is it to win at all costs? Or is it to win with style, panache, and flair? The eternal debate between realists and idealists is as old as football itself and it still rages on to this day.

Tele Santana’s Brazil was arguably the last team to play the game the way it was meant to be played. There was spontaneity, irreverence, and joy in their every display and execution. Fans of football around the world connected with the team as it was almost everybody’s second favorite team.

There was an air of brilliance about them that made people eager to see them again. The fact that they never even made it to the semi-final stage, despite all their artistry and beauty, adds to their mystique. Even though they failed, their uncompromising desire to always play the game beautifully and their aesthetic elegance only added to their legacy.

Tele Santana was a purist in every sense of the word. He was more concerned with the way his team played than the result and abhorred dirty plays or any disruption of the game’s fluidity even if they benefited his team. He gave his players immense freedom to roam over the pitch and improvise their movements and actions in a collective harmony like ballet choreography.

The Fall of Bulgarian Football: A Sad Decline or Corrupted Farce?

After a brilliant qualifying campaign in which they won all their games, the Samba Boys traveled to Spain as the undisputed favorites to win the World Cup. They go by the names of Zico, Socrates, Cerezo, and Roque Junior. They epitomized Brazilian “Jogo Bonito” or ‘the beautiful game’ with their free-flowing, artistic, improvised yet well-choreographed brand of football.

As expected, they hit the ground and ran in the first group stage by winning all three games, USSR, Scotland, and New Zealand with a combined score of 11-2. In the second round, they dispatched the defending champions Argentina 3-1 putting them in a glorious position where they would need only a draw against Italy to qualify for the semifinal.

Tele Santana’s team was everyone’s second favorite side in the tournament. This phenomenon attests to the attractiveness of a style of play that celebrates individual expression and improvisation harnessed in an organized collective recital.

From the purists’ and idealists’ perspectives, jogo bonito died on July 5th, 1982 at Estadio Sarriá in Barcelona. Brazilian football was scarred forever and never recovered.

The fact that the Brazilian side is more revered and celebrated by fans and pundits in Brazil than its winning counterparts in Brazil 1994 and Brazil 2002 speaks to the visceral and emotional bond fans have developed for this team and its enchanting playing style.

Italy drew blood first when Paolo Rossi headed past Waldir Peres from close range connecting with a precise cross from Cabrini (1-0). Brazil responded immediately by imposing their will on the game and Italy retreated to their half. Socrates would equalize (1-1) on a deceptively powerful shot consecutive to a beautiful through pass from Zico who masterfully executed a magic trick to free himself from two Italian defenders.

Italy would show resolve, character, and composure by weathering the Brazilian storm with determination. They would take on the lead again when Rossi intercepted a lackadaisical pass from Cerezo to Junior and went on to beat Peres (2-1). The Brazilians grew annoyed and frustrated as they see their unmatched skills unable to waver the rock-solid Italian defense.

A creative and deceptive ghost overlap run by Junior would free Falcao on the edge of the box to fire past Dino Zoff for the equalizer (2-2). At that particular time, Brazil qualified for the semifinals at top of the group. Italy in this topsy-turvy and scintillating contest had other ideas, and it was again Paolo Rossi who would flip the script. Recovering a deflected shot from Bergomi he fired past Peres a third time to seal the winning goal (3-2).

After the game, critics blamed Tele Santana for not closing down and settling for the draw. To idealists, the Carioca technician stuck to his unwavering conviction and uncompromising philosophy. And that is the essence of who he was.

2. Netherlands 1974

Coach: Rinus Michels

Achievements: Runner-ups World Cup 1974

Key Players: Johan Cruyff, Johnny Rep, Johan Neeskens, Rob Resenbrik, Ruud Krol

Star Player: Johan Cruyff

Formation: 3-4-3

Legacy: Total Football

They go by the names of Johan Cruyff, Willem van Hanegem, Rob Rensenbrik, Wim Suurbier. Led by legendary coach Rinus Michels, they introduced Total Football to the world. Modeled after the Mighty Magyars, it consisted of a style of play that relies on two main concepts: space-time management and positional fluidity.

Rinus Michels figured out that when his team had the ball, they needed to make the pitch bigger to allow his players enough time and space to operate and retain possession. The opposite is also true: when they had to defend, the aim was to shrink the pitch as much as possible to leave almost no space and time for the opposition to maneuver.

The second predicate relies on the principle that players are both versatile and interchangeable enough to allow defenders to go forward in attacking positions while midfielders drop down to defend therefore introducing to the world of football the notion of multiplicity of functions.

Holland started the tournament in style by running over Uruguay, a side still horribly negative yet lacking the confidence of previous years. Johnny Rep scored twice as Johan Cruyff and Johan Neeskens in particular ran them ragged. The men in orange confirmed their status as early favorites and introduced some much-needed inspiration in the tournament.

In their second game, they would register a draw against Sweden (0-0). In their third game, the Dutch would easily secure their berth in the next round by playing their novel, assured, and mesmerizing football against an increasingly dejected and disjointed Bulgarian team.

Exceptionally talented collectively in creativity, tactical nous, and intelligence, Holland with their fast, mobile football scored four past the Bulgarians (4-1). Neeskens, a wonderful midfielder, scored a brace. In the minds of fans and pundits alike they were the team to beat.

In the second round, Holland backed up their credentials by crushing Argentina 4-0, led by Cruyff (with two goals). Rep and Ruud Krol scored in an outstanding performance. Scoring first to ensure an open game, the Dutch overwhelmed the unfortunate South Americans.

In their second game of the second round, East Germany proved no match for the multi-talented Dutch side by losing 2-0. Holland faced Brazil next in Dortmund, an eagerly anticipated clash that would decide the finalist from Group A.

Sadly, threatened by a team of infinitely more talent than their own, the Brazilians roughed up the Dutch to unsettle their opponents. As a consequence of the Brazilians’ aggressive behavior, the Dutch fought back and retaliated. The game degenerated for a period into a spiteful and unpleasant affair.

Slowly Holland composed themselves, however, and moved into their fluid, flexible passing game, bewildering a team who resorted increasingly to petulance and violent challenges. Neeskens and Cruyff ended up breaking them down, each scoring from crisp and decisive movements. Luís Pereira, Brazil’s rugged central defender, was dismissed for one atrocity too many and Brazil crashed out ingloriously.

In the final, Franz Beckenbauer’s immovable object came up against Cruyff’s irresistible force. The most sensational beginning imaginable ensued as Cruyff, following a period of possession football, darted incisively towards the German goal to be challenged clumsily by Uli Hoeness.

With a penalty kick came pandemonium, and Neeskens thumped the ball gratefully beyond Bayern’s fine goalkeeper, Sepp Maier, for 1-0 and no German had touched the ball. Holland pressed, threatening a second goal, Cruyff fraying the nerves of uncertain defenders, but the Germans clung on to them, refusing to buckle.

Their obstinacy was rewarded, wholly against the run of play, when Bernd Holzenbein himself went down under a dubious challenge. The game’s second spot kick converted by Paul Breitner leveled the scores and lifted the confidence of the Germans. Encouraged by their calm and assured captain, they began to impose themselves and found the net again, with Gerd Müeller firing past Jan Jongbloed from ten yards.

Holland, after the break, remained persistent despite enforced substitutions and a largely hostile crowd, and the swaggering genius of Cruyff held sway. But an equalizer proved beyond them, as with Beckenbauer sweeping behind, a disciplined and resolute defense repelled them to the whistle. Germany had won the trophy, Holland the admiration of spectators around the world.

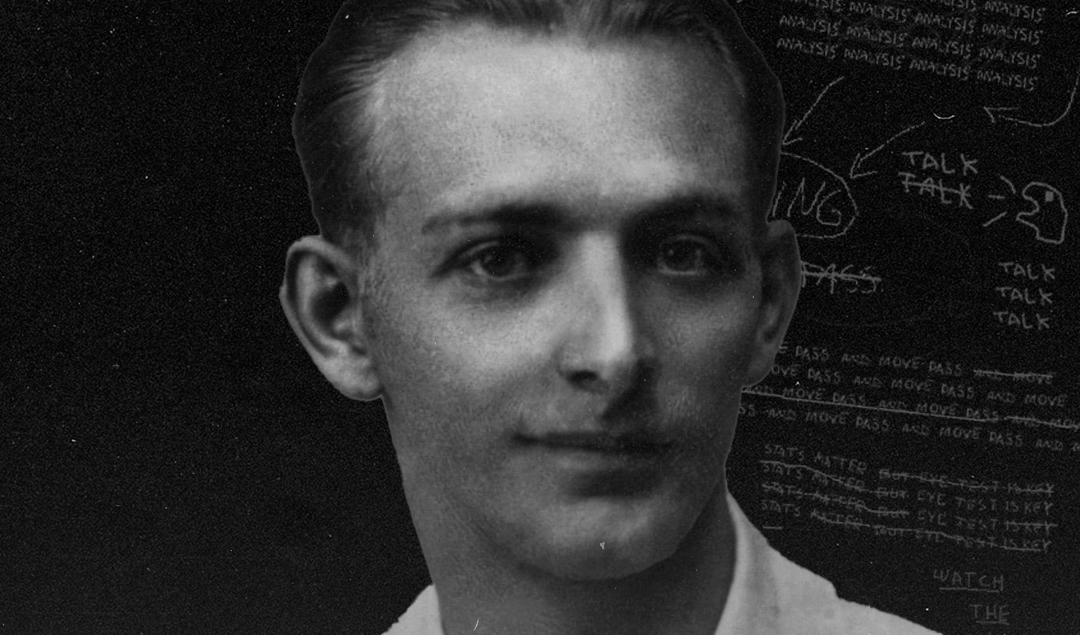

1. Hungary 1954

Coach: Gustav Sebes

Achievements: Olympic champions (1952). From 1950 to 1956, they played 69 games, winning 58 victories, drawing 10, and losing just one in the 1954 World Cup final against West Germany.

Key Players: Ferenc Puskas, Nandor Hidegkuti, Sandor Kocsis, Zoltan Czibor

Star Player: Ferenc Puskas

Formation: 3-2-5

Legacy: Precursors of Total Football, 9 and ½ position

November 25, 1953, is a day that probably changed football forever. On that fateful day, The Mighty Magyars inflicted on the English national team a stinging 6-3 defeat on the mythical grass of Wembley, thus putting an end to their invincibility at home but above all to their misplaced superiority complex. Beyond the score, devilishly spectacular, it is the way that captivated people’s minds.

“We had never seen a team play like this,” said Bobby Robson, a direct witness of the Hungarian demonstration at the Empire Stadium, a few years later. “It’s as if we had just seen Martians land!”

The Englishmen were given a lesson they would never forget by a group of Hungarian players with immense talent: Ferenc Puskas, Zoltan Czibor, Nandor Hidegkuti, Jozsef Bozsik, Sandor Kocsis, and Gyula Grosics. The Golden Team stood out, above all else, for its dizzying style of play made up of close and tight ball control, deadly accelerations, and refined offensive combinations, all at a very steady pace.

The team called Aryanycsapat by the locals was designed by an architect as bold and innovative called Gusztav Sebes. Endowed with a highly developed sense of self-criticism, he paid attention to every detail by analyzing his players’ strengths and weaknesses to continuously make the team better. He also worked on the psychological aspect of the game, in particular with Nandor Hidegkuti who would suffer from stress before the national team’s matches.

For instance, his scrutiny of the Three Lions was a huge factor in that historic triumph at Wembley in what was billed as “The Match of the Century”. From the thickness of the grass to the measurements of the pitch, he investigated all the insight he could gather to his team’s advantage.

The singular objective is always the same: to use all the information he could gather to give his team an edge on the opposition and put his players in training situations that mirror the actual conditions of the game. All this contributed to the demonstration at Wembley, followed by a real humiliation for the English side (7-1!) in the much-anticipated rematch six months later.

Sebes’ team departed from the popular WM at that time to a novel formation akin to a double M (3-2-5): with a 3-man defense and two holding midfielders, and a front 5 including two wingers on each flank, a “nine and a half” in Nandor Hidegkuti, in support of two mobile and hard-hitting inside attackers, Sandor Kocsis, known as “Golden Head”, and Ferenc Puskas, also known as the “Galloping Major” blessed with a divine left foot.

Livorno: A City with a Proud History but an Uncertain Football Future

The Mighty Magyars came to Switzerland to add the only trophy and distinction missing from their near-complete resume: The World Cup Trophy. Right from the onset, they obliterated South Korea 9-0 with a hat-trick from Sandor Kocsis and two braces from Kocsis and Peter Palotas.

In their second game, they humiliated West Germany 8-3 but lost Puskas in the second half due to a violent and reckless tackle from Werner Liebrich. The Germans were so outclassed and embarrassed they had to resort to illegal and violent means to counter this magnificent Hungarian team. In the quarterfinals, without Puskas injured, “The Battle of Bern” squared against Brazil was a tough and hotly contested game where they came up victorious 4-2.

The final would be a rematch against West Germany. Sebes was given a huge boost with Puskas coming back from injury. The Hungarians started the game the same way they did the first encounter by scoring two goals in the opening 8 minutes. At this moment, in the minds of all fans and pundits alike the Hungarian team’s crowning was all but inevitable and a foregone conclusion.

Unfortunately, West Germany would score two goals in the next ten minutes to level up the game. With nerves and tempers flaring, the Germans would score a third goal that put them ahead for good at the 84th minute and they held off the Hungarians until the final whistle.

Hungary would miss the most important match in its history: Olympic champion in 1952, it lost 2-3 in the final of the 1954 World Cup in would be infamously dubbed as the “The Miracle of Bern”.

Fans around the world would bemoan the fact that Ferenc Puskas was denied an equalizer in the dying seconds of the final as the referee wrongly deemed the attempt to be offside. They also had some reservations about the second German goal that should itself have been flagged for offside.

By: Ralph Dominique Ganthier / @ralphganthier

Featured Image: @Juanffrann / Getty Images